Sermon for the Fourteenth Sunday after Trinity Year C “For all who

advertisement

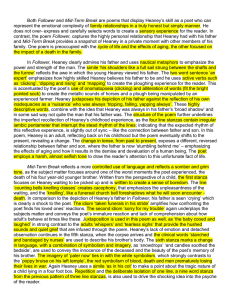

Sermon for the Fourteenth Sunday after Trinity Year C “For all who exalt themselves will be humbled and all who humble themselves will be exalted”. Luke 14.10. It’s a strange and compelling coincidence that in the same week that the British government has lost a motion on a decision for military action in Syria, the poet Seamus Heaney has died. We might well imagine a world of difference between the life of a poet and that of a politician. But we judge on what must be the case of the matter. It is typical for most people to consider politicians as above all practitioners of a dark and devious art. But this of course is not always the case. We equate politics with deviousness. But that is not always the way it is. But most people would find it harder to consider the life of a poet, and of what kind of person they imagine a poet to be and of what kind of life they might live. There is no one template. But the possibilities are endless. The Irish Taoiseach, Enda Kenny described Heaney on behalf all the Irish people. He said “For us, Seamus Heaney was the keeper of language, our codes, our essence as people”. He was a Catholic Irishman from Londonderry and yet he was every Irishman. A citation he was given in 1995 for The Nobel Prize for Literature read “for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past”. Our former poet laureate, Andrew Motion commented that to read Heaney’s poetry was to “feel the benediction of his kindness”. The actor Liam Neeson has said that with the death of Heaney “Ireland had lost a part of its soul’. Only a humble man could be given such accolades. Only someone, who spoke the truth, as we all understand it in its most profound sense. In today’s Gospel we are given the simple figure of the instruction in humility. It is the parable of the invitation to the wedding banquet and of two pieces of advice, the first one is to the guest to take the lowest seat, so that he may be called higher. Secondly there is the advice to the host, instructing him to invite those he would never imagine inviting, the poor, the lame and the blind; in other words beggars who could not re-pay the invitation in kind. On its own the parable would be quaint were it not for the context in which it is being delivered. Related as it is to the life of Christ and his Gospel message, it becomes for the Church a parable for the values of the Kingdom of God. The earthly banquet equates to the heavenly banquet as the occasion which sees the gathering in of those who have been invited to the feast, the place in which the divine and the human life finds its place of understanding and rest. But this parable also has ‘teeth’. For when Jesus teaches the values of the Kingdom, and where this parable points to the quality of humility, so a strong and searching light is cast on those types of behaviour where human pride is to the fore, and where there is recourse to take, if needs be by an act of greed, or force or vanity, the higher place where we may assert our own right to be ‘on top’, our own privileged place of right, at the expense of others, no matter what. The juxtaposition of the poet’s death and the vote on war is therefore a powerful sign for our own times, a telling one. Only a life of deep reflection is capable of recognising that which is most profoundly and most humanly true. It was Bishop Richard Holloway of Edinburgh who instructed us “to live the examined life, which tests itself for its own prejudices and assertions. For only then will we prevent ourselves from gaining knowledge for its own sake while at the same time throwing away its key”. Only a Heaney could put in a form of poetry the underlying truths that lead to a government motion on the use of bombing in the cause of an apparent right: Who would connive In civilised outrage Yet understand the exact And tribal, intimate, revenge. The word ‘humility’ signifies, as with the poet Seamus Heane, a very grounded closeness to Mother earth. It relates to the Latin word ‘humus’ meaning earth. It is not the false humility which is full of itself. As a farmer’s son, he had the soil of Ireland in his finger nails, and rather than rail against the Northern Ireland conflict, which was at its height when Heaney was writing at his height, he used the image of the thousand years old bodies, dug up in Irish bogs, to write about time and the consequences of living out of time. He once said he had ‘an early warning system telling me to get back inside my own head’ whenever politics was discussed. Though he left the countryside and taught English first in Belfast and then in Dublin as a young man, he did not forget his farming roots. He fondly remembered watching his grandfather cutting turf for peat, and taking a bottle of milk to the old man who would straighten up just long enough to drink it before bending over his spade again. He pictured himself working in the same way, digging out words with the nib of his pen. For me is humility. Heaney was a great believer in what he called ‘learning by heart’. Especially learning poems by heart. And the Christian Faith lays great store on the heart as the place for all our decision-making. Humility is the ground, the grounded place. It is the place where lies our true centre and personal, spiritual and moral equilibrium, our sense of balance and perspective and our true humanity. It is the place where we may ‘learn by heart’. We are asked to return once more to state of true humility. This is not a place of weakened or thin humanity, but one which is most fully alive to the world in which it is living, and, one which shines that same strong searching light on the world as it is in its own state of vanity. A word which at the same time means proud and also empty or fruitless. When Jesus teaches the values of the Kingdom of God on this earth, his is very much leading where the poet follows on with the learning of the essential and wise things ‘by heart’, the leading of the deeply active/reflective life, the weighing of words and the celebration of their meaning and depth. Above all in Kingdom teaching, strong attention is placed on our lives on our own state of becoming and of the close relationship between the observation of things and the consciousness that as Yeats, once said, ‘everything we look upon is blessed’. The Kingdom is that place where life itself, wherever it goes on, whether as kind or brutal is in God always waiting as we might say ‘in potential’, waiting, as it were, for its own transformation into his likeness and being. Waiting for that which belonged to Heaney, ‘of the benediction of God’s kindness’. A true and decent humanity never discards this possibility, and nor should we…