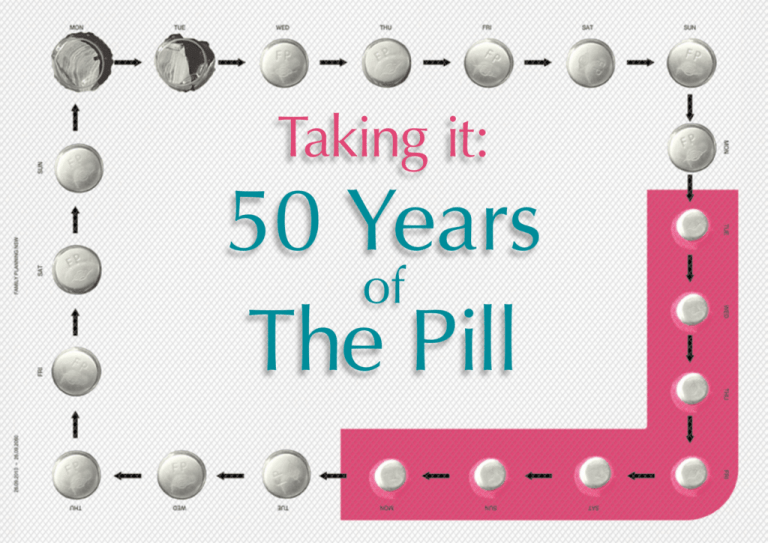

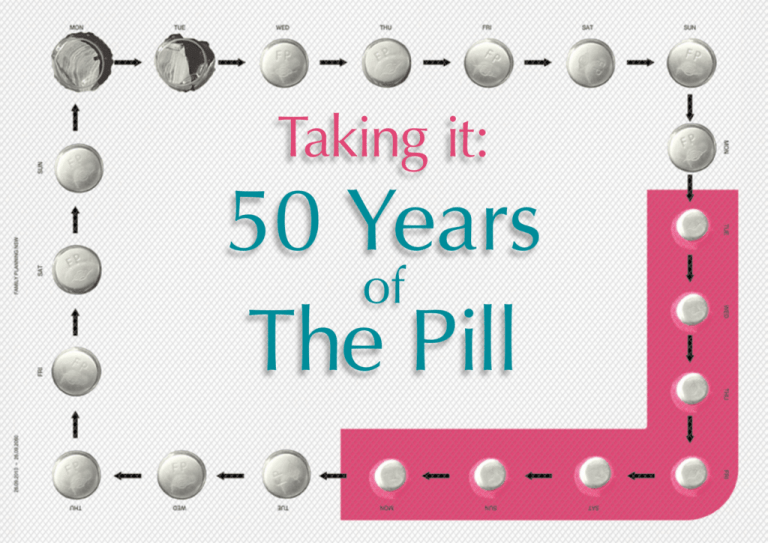

Taking it:

50 Years

of

The Pill

A model of synthetic oestrogen.

Co n te n t s

Introduction

Personal Reactions

The Future

01

29

41

Chris Udy

Nina Funnell

Ann Brassil

Dr Devora Lieberman

32

43

History

Wendy McCarthy AO

Foreword –

Family Planning NSW

07

A potted history

of hormonal contraception

Dr Terri Foran

13

50 years of the Pill – A medical, social and

political commentary

Dr Edith Weisberg OAM

I rarely marry virgins anymore…

The Pill and I — A personal

and political reflection

35

50 years of taking it

Jane Caro

37

There is a long way to go…

Hopes and dreams: six wishes

for the future of contraception

in Australia

Dr Caroline Harvey

47

Fifty years from now

Dr Christine Read

How the Pill changed my

life — Reflections of a

Generation X teenager

Sophie McCarthy

17

Pills, sex and family planning…

Dr Deborah Bateson

19

The Pill is 50 years old…

Professor Gab Kovacs

23

The medicalisation

and democratisation

of contraception Dr Stefania Siedlecky AM

“Taking It: 50 years of The Pill” 2010.

A collection of essays published by Family Planning NSW to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the oral contraceptive pill.

Edited by: Christine Read MBBS ThA FAChSHM Grad Cert PH

Published by: Family Planning NSW, 328-336 Liverpool Rd, Ashfield 2131

F o rew Or d

“Access to contraception has been one of the

defining influences in my own life, particularly

in allowing me to choose the timing and

spacing of my own children and the impacts

this has had on my ability to pursue a

professional career and support my family”

Ann Brassil

Chief Executive Officer

Family Planning NSW

The 50 year commemoration of the launch of

the first oral contraceptive pill in Australia is an

important anniversary in so many ways.

It defines the moment in time from which

women could easily and efficiently manage their

fertility, it signals the point from which human

scientific endeavour created a way for society

to manage population growth effectively with a

culture of invention and enquiry that is ongoing,

it allowed a whole generation of baby boomers

to make choices about their futures with a

certainty their parents never enjoyed and it was

controversial and led to intense examination of

sexuality, women’s rights, society’s accepted

conventions and moral judgements. It became

a political issue and caused changes in health

service provision and the spread of the family

planning movement.

Virtually all of these issues have become intrinsic

to our mainstream culture, yet we still have a

long way to go.

There is a sexual ‘double standard’ in Australia.

There is inequity of reproductive and sexual

healthcare between indigenous and non

indigenous peoples and for a range of

marginalised groups such as the young and

people from some cultural backgrounds.

Some states have taken a sensible ‘health

based’ approach to abortion legislation but it

still remains within the Crimes Act in NSW and

a young woman and her partner are

facing possible imprisonment for procuring an

abortion under Queensland’s antiquated law.

The implementation of comprehensive

reproductive and sexual health education in

schools in Australia remains a challenge.

Access to contraception has been one of the

defining influences in my own life, particularly in

allowing me to choose the timing and spacing

of my own children, and the impacts this has

had on my ability to pursue a professional

career and support my family. This publication,

composed of essays and the personal opinion

of its contributors provides a fascinating window

into history, personal experiences, intellectual

grappling and questions for the future. I hope

you enjoy it and find the articles as compelling

as we have.

Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l | Page 3

“I feel fortunate to never have lived in a

time or place when I did not have easy

access to reliable, affordable contraception,

and the right to decide what to do about

an unplanned pregnancy should that

contraception fail. I hope that it doesn’t

take another 50 years for all women to

be able to feel the same”

Dr Devora Lieberman

President

Family Planning NSW

When I first started working as a contraception

and abortion counsellor at Planned Parenthood

of New York City in 1984 (my summer job for

three years during Uni), I was given a Zip-Loc

bag full of all of the available contraceptive methods

for demonstration purposes. There was a condom,

a can of spermicidal foam, a diaphragm, yellowed

with age and with a hole in the middle so it

wouldn’t be stolen, a Lippes Loop IUD with a

blue nylon string attached, a Today sponge and,

of course, plastic dial packs of lolly-coloured

pills. The yellow packs contained the 50 mcg

pills, and the peach the 35. The options were

few, the hassles and side effects, many.

Much has changed in the last 25 years! Lippes

Loops disappeared in the mid-eighties when

sales were decimated following the disaster that

was the Dalkon Shield. And who could forget

the Seinfeld episode when Elaine scoured every

pharmacy in New York when they stopped

making sponges? Pills have gone through

myriad formulations – lower doses, multiphases, newer progestins – whose introduction

was always carefully timed with patent expiry.

The first decade of the new millennium has seen

a resurgence of contraceptive technology.

Implanon in 2000, followed quickly by Mirena,

offered women extremely reliable “set and

forget” contraception. NuvaRing® in 2005 gave

the monthly option, with the advantage of being

able to stop it without seeing a doctor.

I feel fortunate to never have lived in a time

or place when I did not have easy access to

reliable, affordable contraception, and the right

to decide what to do about an unplanned

pregnancy should that contraception fail.

I hope that it doesn’t take another 50 years

for all women to be able to feel the same.

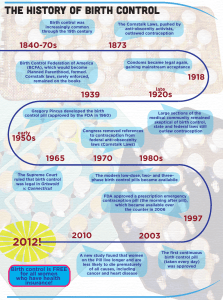

A Timeline for 50 Years of The Pill

1960

• The oral contraceptive pill, Enovid

(Searle) launched in the United

States May 1960.

2002

• Packaged levonorgestrel

emergency contraceptive

pill available in Australia.

2003

1961

• Anovlar

(Schering)

marketed in

Australia – the

second country

in the world to

have the oral

contraceptive pill.

2001

1965

• The US Supreme Court ruled that

married women have a constitutional

right to privacy that allows them to

obtain contraception.

1998

• Contraceptive implant containing

progestogen only –­ etonogestrel

available in Australia and on PBS.

• Lower dose (20mcg)

oestrogen pills become

available in Australia.

• A hormone releasing

progestogen only (levonorgestrel)

intrauterine device available

in Australia and goes on PBS

in 2003.

• “Sex and the Law” – The first

health workers’ guide to sex

and legal matters is published

by Family Planning NSW.

2004

2005

• United States FDA approves a

prepackaged pill regimen with

four placebo breaks per year.

• Emergency contraceptive

pill available over the counter

at pharmacies.

• Australian fertility rate: 1.75 births

per woman.

• The “Baby bonus” is

introduced to raise

Australia’s birth rate.

• It was noted that only 15.9% of

countries, which were identified in

2005 as failing to achieve gender

parity in both primary and secondary

schools, will achieve this Millennium

Development goal by 2015.

1966

• Margaret

Sanger,

birth control

pioneer dies.

1995

• Venous thromboembolism

(bloodclots) media stories in UK

about third generation progestogen

containing – lead women to cease

taking their pills and a marked rise

in the abortion rate.

2006

• Combined hormonal vaginal ring

available in Australia.

• Australian teenage birthrate:

17.3 per 1000 women.

1967

• Prof Rodney Shearman reports to

WHO meeting: Australia has the

highest rate of use of The Pill in

the world.

1994

• International Conference

on Population Development

in Cairo commits to ensure

reproductive health rights for

all, including family planning

and sexual health.

2007

• UN Millennium Development Goal 5(b)

is introduced: to achieve universal

access to reproductive health services

by 2015.

Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l | Page 5

1968

TIMELINE

• Papal encyclical – Humanae vitae

“On the Regulation of Birth” –

Reaffirmed the positive value of

sex (in marriage), but rejected

contraception for Catholics.

1992

• Pills containing cyproterone acetate

is available, licensed specifically for

treatment of acne and androgenic

symptoms, the first recognition of

non contraceptive benefits with oral

contraceptives.

1969

1970

• Man lands on the Moon.

1971

• “The Female Eunuch” by Germaine

Greer is published.

• L ow dose oestrogen (30 mcg ethinyl

oestradiol) pills are available.

1987

• Australian teenage birthrate:

55.5 per 1000 women average

of 2.95 births per woman.

• 38% Australian women taking

the Pill.

1985

• Medicare introduced to

Australia and card available

to 15 year olds.

• Pills containing

“third generation”

progestogens;

desogestrel

and gestodene

available.

• Biphasic and triphasic pills

available, mimicing the

hormone pattern in the

menstrual cycle and reducing

the overall load of hormone.

1980

• The 20th

anniversary of

the Pill described

as “unhappy”

in the Sunday

Telegraph.

Women are

interviewed about adverse effects,

but still enormously popular.

2008

2009

2010

• Pill with a regimen of 24 active

pills and 4 placebo tablets

launched in Australia.

• The first oestradiol (natural

form of oestrogen) pill available

in Australia.

• J ulia Gillard – First female

Prime Minister of Australia.

• Worldwide 1 in every

10 women has an unmet

need for contraception.

1972

• L uxury tax removed

and Pharmaceutical

Benefits Schedule

(PBS) listing of the

Pill by Whitlam

government.

1973

• Family Planning Association

branches appear in each state

of Australia.

• Legal maturity reduced from

21 to 18 years.

The

Future

• New ways of packaging pills with bleeding breaks to be

potentially under the woman’s control, plus new delivery

methods such as a wafer that dissolves on the tongue.

• More work to be done on reproductive rights worldwide

and removing abortion from criminal codes.

• Family planning services and meeting Millennium

Development Goals in developing countries.

Hormone production before the 1950’s.

Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l | Page 7

A p otted History of H o rm o n a l Co n trac e pti o n

“In his dystopian 1932 novel Brave New World

Aldous Huxley described a future in which sex was

depersonalised and social order maintained by the use

of the psychoactive medication “soma.” Twenty eight

years later he was asked to write a commentary on

the state of contemporary society through the prism of

his earlier predictions. It was in this subsequent work,

Brave New World revisited, that the term “the Pill” –

with its distinctive capital P-came into existence.”1

Terri Foran

Sexual Health Physician, Lecturer

School of Women’s and Children’s Health,

Medical Faculty, University of New South Wales

Since the dawn of time humans have sought

to control their fertility. Initially women relied

mainly on amulets and superstition but even

in the ancient world contraceptive douches,

pessaries and sponges were used across many

civilisations and religions. Christianity developed

its official position in the 5th century when

St Augustine declared that sex without the

intention to procreate was unconditionally

immoral and illicit, thus effectively prohibiting any

form of contraception. And this influential early

Church philosopher knew quite a bit about sex,

having had several mistresses and one 14-year

common law relationship prior to his conversion

to Christianity. During these libidinous years

Augustine’s self confessed maxim was “Grant

me chastity…but not yet.”

It would appear that the majority of the

mediaeval population identified more closely

with the early, pre-sanctified Augustine when it

came to sex and continued to utilise traditional

contraceptive practices with varying degrees of

success. However, it was the advent of cheap

mass-produced vulcanised rubber condoms

in the mid 1800s which really took effective

contraception to the general population.

Couples took full advantage of this new

opportunity to limit the size of their families.

In the 1800s the average American woman gave

birth seven times, by 1900 that rate had halved,

remaining stable until 1960 at which point it

halved again with the release of the Pill.2

The concept of hormonal contraception also

has a long history. Mexican women traditionally

consumed Barbasco yams as a means of

avoiding unintended pregnancy. This tuber is

rich in plant hormones and was the original

source of the steroids used in modern

contraceptive pills and menopause therapy,

until these could be synthetised more cheaply.

The early women settlers in New Brunswick

in Canada borrowed from a local indigenous

tradition and relied on a monthly brew of dried

beaver’s testicles steeped in alcohol for their

contraceptive needs. There is even an

antipodean connection, though not a human

one, in the discovery by Australian farmers in

the 1940s that ewes grazing on hormone-rich

red clover produced significantly fewer lambs

the following season.

The Contraceptive Pioneers

The late 19th century saw a tension between

the neo-Malthusians, who advocated population

control as a means of managing limited world

resources, and the religious and pro-natalist

groups, who linked a growing population with

traditional family values and economic success.

In much of the world this debate was managed

politely. Continental gynaecologists quietly

developed more effective contraceptive

methods, such as stem pessaries and

individually-fitted diaphragms for their wealthier

patients, while in the United Kingdom the

botanist Marie Stopes founded women’s clinics

and daringly advocated sexual pleasure as a

female right.

Page 8 | Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l

The first Australian birth control clinic opened

its doors in Sydney in 1933, under the auspices

of the Racial Hygiene Association of New South

Wales. This organisation advocated “the

selective breeding of future generations for the

elimination of hereditary disease and defects”

and most of the early birth control pioneers had

a similarly eugenic philosophy. The belief that

the people most likely to have the largest

families were those least able to care for them

was widely-held and for this reason most of the

population control efforts were directed towards

the socially disadvantaged. When examined

through 21st century eyes these beliefs smack

heavily of classism and racism and it is

understandable then that the writings of many

of these early pioneers of birth control are now

open to modern criticism. Marie Stopes, for

example, was an ardent admirer of Hitler,

and in 1939 sent him a copy of her own

sentimental love poems complete with a

gushing covering letter.3

It was, perhaps, inevitable that a more hostile

clash occurred in the United States where

positions were even more polarised. One of the

more interesting characters in this struggle was

Margaret Sanger, who is actually credited with

coining the term “birth control”. One of 11

children, Sanger was born in 1879 into the strict

Catholic Higgins family. Her mother, who she

idolised, died at only 50 years of age from

tuberculosis. The young Margaret however

attributed the death to her mother’s eighteen

pregnancies and held her father directly to

blame. “You caused this.” she accused him.

“Mother is dead from having too many children”.

She later worked as a community nurse in the

slums of New York. Distressed by the numbers

of women in her care who died as a result of

numerous pregnancies or from the

complications of backyard abortions, she

later wrote “No woman can call herself free

who does not own and control her own body.

No woman can call herself free until she can

choose consciously whether or not she will be

a mother.”4

Scientific Advances and Hormonal Contraception

As early as 1921 the German physiologist

Haberlandt had demonstrated the possibility

of hormonal contraception when he rendered

rabbits infertile by injecting them with corpus

luteum extract.5 Researchers in the 1930s and

40s, such as Inhoffen, Hohlweg, Russell,

Makepeace and Djerassi, developed the steroid

hormones which were later to become the basic

ingredients of oral contraceptives.

These experiences acted as a personal

catalyst for Sanger and by 1910 she was

going door‑to‑door teaching women about

contraception. In 1916, she established the first

birth control clinic in the United States and by

the 1940s there were 800 similar clinics across

the country. To a woman as passionate as

Sanger however, the diaphragms, condoms and

pessaries available at the time were frustratingly

fallible. As early as 1912 she had begun to refer

to the “magic pill” in her writings – a pill which

would allow couples the ultimate choice in when

and whether they reproduced. It was not until

the 1950s however that advances in steroid

chemistry allowed that vision to become a

reality. Sanger lived just long enough to see the

US Supreme Court rule in 1965 that “the use of

contraception is a constitutional right”. After this

announcement friends propped the terminally ill

86-year-old rebel up in her bed, and it is

recorded that she celebrated the event by

drinking vintage champagne through a straw.

In 1951 Margaret Sanger was by chance

introduced to the brilliant but abrasive

physiologist Gregory Pincus who had

recently set up his own research facility after

a disagreement with his Harvard colleagues.

Pincus and his collaborator, the infertility

specialist John Rock, were experimenting

with hormones that might assist conception.

Sanger realised that this work might finally be

the key to the development of her “magic pill”

and persuaded her wealthy collaborator,

Katharine McCormick to endow the research

facility with enough funds to enable an entirely

new project. Pincus and Rock were charged

with investigating whether hormones could

also be used as an effective way of preventing

pregnancy. Since it was still a felony at that time

to administer contraception in their home state

of Massachusetts, the pair was forced to

conduct their early pill trials in Puerto Rico.

Poster for the Racial Hygiene Association

of NSW 1933.

Margaret Sanger, established the first birth control clinic in the

United States.

Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l | Page 9

The first contraceptive formulation administered

to the women in the trials contained only

progestogen. Though this preparation effectively

prevented ovulation there was a high rate of

unpredictable vaginal bleeding which severely

limited its acceptability as a contraceptive.

However at some point during the early trials

a batch of pills was inadvertently contaminated

during the manufacturing process by a small

amount of synthetic oestrogen. The women

receiving this batch had significantly less

bleeding than the other women on the trial and

so, through sheer serendipity, the concept of a

combined pill was born. A descendent of this

accidental combination was later to become

“Enovid,” the first contraceptive pill to be

approved for use in the United States.

Pincus and Rock also made a decision to

schedule a regular break from hormone tablets

every four weeks. This was partly from a desire

to provide women with a regular menstrual-like

bleed but also because the devoutly Catholic

Rock believed that this would make their

preparation akin to natural family planning and

therefore acceptable to his Church. He was

later to be proved wrong when the 1968 papal

encyclical “Humanae Vitae” reiterated its

complete objection to oral contraceptives and

all other “artificial” methods of birth control.

Rock however maintained his position until he

died, despite a great deal of personal pressure

and the threat of excommunication. One angry

woman wrote to him not long after the Pill was

approved “You should be afraid to meet your

Maker!” “My dear madam,” Rock wrote back,

“in my faith, we are taught that the Lord is with

us always. When my time comes, there will be

no need for introductions”.

Marketing the Pill in America and Beyond

In late 1957 the pharmaceutical company

Searle received regulatory approval to

market Enovid in the United States for the

treatment of menstrual disorders. Following

a virtual epidemic of this condition, the

product was subsequently given an official

indication for contraception in May 1960.

Australia was only the second country

in the world to approve a combined

preparation for contraceptive use with the

release of the Schering product, Anovlar,

in February 1961.

All these early formulations contained much

higher hormonal doses than those found in

modern contraceptives. They also had a higher

rate of side effects, including the more serious

complications of clots and strokes, and on the

whole both regulatory authorities and the

medical profession took a fairly conservative

position on their use. Initially the Pill was

restricted to married women and even then,

was often prescribed only after the woman had

completed her family. Searle executives were

however supremely optimistic as to the Pill’s

wider potential. An early in-house newsletter

exhorted their sales team to “weed out all the

negative points and convince doctors to get

patients started on Enovid today…”

Few would suggest that the Pill initiated the

sexual revolution but there is no doubt it fell

on fertile social ground. The 60s saw the

rise of the Women’s Movement in which

activists sought increasing freedom on

many fronts: political, legislative, workplace

as well as reproductive. By the late 1960s

women centred health clinics had been

established in most Western countries.

These were usually left leaning in philosophy

and challenged conventional perceptions

about women’s sexuality. Many of the health

professionals in these centres had no objection

to providing contraception to sexually active

young women regardless of their marital status.

Even fundamentally more conservative doctors

recognised in the Pill a more scientific method

of contraception which did not require the

previously “messy” business of fitting a

diaphragm. Thus as the historian Beth Bailey

observed “the Pill was a wonder drug not simply

because of its effectiveness for women but

because of its convenience to those who

prescribed it”.7

What has been the social impact

of the Pill on Women and Society?

During the years of the Second World War,

unprecedented numbers of women were

encouraged to assume roles in industry and

commerce in order to support the war effort.

With the end of hostilities most resumed their

previous domestic roles, but it could not be

expected that such an immense social upheaval

would not have an impact. The leitmotif of the

1950s was home, family and conservatism.

At least for some women, however, this cosy

domesticity masked what was in effect a galling

lack of freedom and opportunity. This was a

time when Australian women were forbidden

from entering a public bar and automatically

forfeited their public service employment upon

marriage. Premarital sex was at once forbidden

and widespread and if an unmarried woman

was unlucky enough to get pregnant she had

only three choices – public shame and adoption

of the child, a shot-gun marriage to the often

unwilling father or a hazardous illegal abortion.

1961 – The first oral contraceptive pill released in Australia.

Page 10 | Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l

One of the problems in examining the true

impact of the Pill is untangling it from the social

events which were occurring at the time of its

genesis. The post-war period was a hive of

industry, invention and an overwhelming

optimism that there was no problem which

medical and technological advances could not

address. The 60s and 70s saw immense social

change – a time when long-accepted social

mores were held up to question. It was the era

of the sexual revolution, peace and civil rights

movements and a growing youth culture which

sought to distance itself from the values of its

parents. Germaine Greer’s totemic ‘The Female

Eunich8’ was published in 1970 and prompted

many women to question the gender roles and

societal expectations previously imposed on

them and to develop aspirations beyond that

of being someone’s wife or mother. The Pill

effectively separated the concepts of sex and

reproduction, made contraception “modern”

and laced it under the woman’s own control.

Increasingly, women chose to exercise this

control in order to enter higher education,

to aspire to careers and to delay marriage and

family. Employers too, saw the disappearance

of one of the last excuses for not employing

young women – that they would simply leave

when they fell pregnant. The Pill did not cause

these changes but it certainly enabled and

sustained them.

The Pill saw contraception transformed into a

more esoteric process in which the mechanics

of sex itself need never be mentioned, thereby

enabling wider discussion and debate. This shift

to a more “scientific” focus, and the inevitable

controversy surrounding the Pill’s release, made

it a prime subject for coverage in the press and

on the television sets which were gradually

finding a place in most living rooms. One of the

fathers of hormonal contraception, Carl Djerassi,

was to reflect in a 2007 interview “No one

expected that women would accept oral

contraceptives in the manner in which they did

in the 60s. The explosion was much faster than

anyone expected”.9 And explode it did, with the

use of the Pill in the United States climbing from

400,000 women in 1961 to over 3.5 million only

four years later.2 Australians also responded

enthusiastically to the idea of more effective

contraception and by 1971, 38% of women of

reproductive age were taking the Pill.10 The

removal of sales tax and the addition of the Pill

to the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits

Scheme in 1972 further increased its availability

and use in this country.

In 1969 the British-American anthropologist

Ashley Montagu ranked the Pill’s

importance with “the discovery of fire”

and went on to predict that “the Pill would

not only emancipate women and make

premarital sex acceptable”, but would

“allow for the overall rehumanisation

of mankind”.11

Hyperbole perhaps, but there is no doubt that

the past 50 years have seen women claiming

both economic equality and the right to

explore a sexuality outside the boundaries of a

traditional marital relationship. Western countries

saw a growing acceptance of premarital sex,

single-parenting, alternative family units and

dual-income households. More couples made

a conscious decision to remain childless and

those that did have children usually opted for

smaller families and had them later in life. This

trend has in fact continued to the point where

many now feel this delay has been pushed

almost beyond biological limits, with statistics

indicating that age-related infertility is now the

commonest reason for referral to Australian

fertility clinics. We may also be in the throes of a

reaction to the demands that such an enormous

social change has placed on the population.

The early 21st century has seen a growing

number of women questioning the desirability

of frantically juggling both career and family

commitments and opting for a more traditional

stay-at-home approach to parenting.

For some social commentators there has been

a continual reassessment of the Pill’s impact.

In her first article for Esquire Magazine in 1962

the influential US feminist Gloria Steinham took

as her theme the Pill’s potential to revolutionise

the lives of women.12 Importantly she also

cautioned that for such a revolution to be

effective there must be a corresponding change

in the attitude of men. Steinham famously later

described the Pill’s impact as “overrated”, but

when interviewed recently on the occasion of

the Pill’s 50th anniversary it appeared she had

again reconsidered her view “There have always

been methods of contraception, but this was

much more dramatic, complete and public”

she said. “It really changed the image of

women and of women’s lives”.13

And it is true that feminists have long had an

uneasy relationship with the Pill. On one hand

it offers the freedom and female reproductive

control promised by Sanger and the other early

contraceptive pioneers. Many feminists however

hold a profound distrust of a medical and

scientific paradigm which they view as malegendered in its focus and motivated by control.

It is also undeniably and shamefully true that

some authorities have sought to impose

contraception on women least able to make

an informed choice or as a matter of national

population control policy. Another potent

suspicion held by many feminist commentators

is that the risks of hormonal contraception are

minimised by big pharma in an attempt to

maintain and boost sales of their products.

Research published in March 2010 perhaps

provides a degree of reassurance on this matter.

A study conducted by the Royal College of

General Practitioners in the United Kingdom

examined the health of a group of women over

nearly 40 years of pill use.2,14 These researchers

found an overall positive effect and concluded

that women on the Pill had lower rates of death

from all cancers (notably bowel, uterine and

ovarian) as well as lower rates of heart disease.

There are many conservative groups, the

most vocal being the Catholic Church, who

maintain strong objections to the Pill and to the

reproductive freedoms it enables. Such groups

link the availability of effective contraception to

immorality, promiscuity, the objectification of

women and the erosion of traditional family

structure and values. It is easy to dismiss these

objections as being relevant only to a small and

diminishing minority and it is true that even

practising Catholics are often able to separate

the religious from the personal. Catholic Italy, for

instance, has one of the lowest birth rates in the

world and a 2002 survey in the United States

showed that the contraceptive use of Catholic

women aged 15-44 years was virtually identical

to that of US woman in general.15 It is, however,

in the developing world, where Christian

doctrine remains more influential and

unchallenged, that pronouncements against

contraception may have a profound impact

on the lives of women. In the words of the

controversial Swiss Catholic theologian Hans

Kung, “This teaching has laid a heavy burden

on the conscience of innumerable people,

even in industrially developed countries with

declining birth rates. But for the people in many

under-developed countries, especially in Latin

America, it constitutes a source of incalculable

harm, a crime in which the Church has

implicated itself”.16

Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l | Page 11

In the West it is now hard to imagine life without

the Pill. Yet there are countless women in many

parts of the world who have been bypassed

by the choices now seen as a right by their

Western sisters. These women remain trapped

by poverty and restriction. They would be

unable to afford effective contraception even

if their culture and religion allowed it and many

still experience the dangers of multiple

pregnancy and illegal abortion which would

have been immediately recognisable to the

young Margaret Sanger a century ago.

Perhaps it is only when all women across the

world, regardless of their race, colour or religion

have equal access to reproductive rights that

we will truly be able to assess the final impact

of the Pill.

The final word should again go to Huxley.

In a series of lectures on population control

delivered at the University of California in

1959 he commented on the inescapable

link between science and philosophy when

examining the impact of contraceptive

technologies. “The problem of the control

of the birth rate is infinitely complex”,

he said. “It is not merely a problem in

medicine, in chemistry, in biochemistry,

in physiology; It is also a problem in

sociology, in psychology, in theology and in

education.”17 More than half a century later

we are still grappling with the same issues.

References

1. Huxley A. Brave new world revisited. New York:

Harper and Row, 1958: p138-139

2. Gibbs N. The Pill at 50 Sex, Freedom and Paradox.

Time Magazine May 2010. Accessed June 2010

at- http://www.time.com/time/

printout/0,8816,1983712,00.html

3. Warner G, Marie Stopes is forgiven racism

and eugenics because she was anti-life, in:

The Telegraph, Aug. 28th, 2008. Accessed June

2010 at- http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/news/

geraldwarner/5051109/Marie_Stopes_is_forgiven_

racism_and_eugenics_because_she_was_antilife/

4. Sanger M. Woman and the New Race. Chapter 8.

Birth Control – A Parent’s Problem or Woman’s?

New York. Brentano’s. 1920.

5. Haberlandt L. Hormonal sterilistaion of female

animals. Munchner Med Wochenschr 1921; 68:

p1577-1588

6. Solinger R. Pregnancy and Power: a short history of

Reproductive Politics in America. NYU Press, New

York. 2005 p173

7. Bailey B. Prescribing the Pill: Politics, Culture,

and the Sexual Revolution in America’s Heartland.

Journal of Social History. 1997; 30 (4): p827-856

8. Greer G. The Female Eunich. Paladin. London 1970.

9. Wood G. Father of the Pill. The Observer.

Sunday April 15, 2007. Accessed June 2010 at

http://www.djerassi.com/observer2007/index.html

10. Ware H. Australian Family Formation Project,

Department of Demography, Australian National

University, Canberra. 1973

11. Montagu A. Sex, Man and Society. G. P. Putnam’s,

New York. 1969. p13

12. Steinham G. The Moral Disarmament of Betty Coed.

Esquire. September 1962. p155

13. The Pill Turns 50-Marking Its Golden Anniversary,

Gloria Steinem, Hilary Swank, Dr. Jennifer Ashton

Discuss Its Impact, Future. The Early Show CBS

News, May 6, 2010. Accessed June 2010 at http://

www.cbsnews.com/stories/2010/05/06/earlyshow/

health/main6465686.shtml

14. Hannaford PC, Macfarlane TV, Elliott AM, Angus V,

Lee AJ. Mortality among contraceptive pill users:

cohort evidence from Royal College of General

Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. BMJ 2010;

340:c927

15. Ohlendorf J, Fehring RJ. The Influence of Religiosity

on Contraceptive Use among Roman Catholic

Women in the United States. The Linacre Quarterly

74.2 (2007): p135-144

16. Mumford SD, The Life and Death of NSSM 200:

How the destruction of Political will doomed a

US population policy, Center for Research on

Population and Security, Box 13067, Research

Triangle Park, NC 27709); 1994; p203.

17. Huxley A. The population explosion. In: the human

situation, a series of lectures delivered at the

University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1959.

Edited by Piero Ferrucci. Originally published

New York: Harper and Row, 1977.

Contraceptive options.

Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l | Page 13

5 0 y ear s of the pill – A m e d i ca l , s o c i a l a n d po l i t i cal c o mme n ta ry

“Modern contraception has given women

the potential to plan their lives, complete

their education, and make career decisions.

Motherhood is an option to be exercised not

a compulsion. Pregnancies can be planned

and adequately spaced, improving the health

of both mother and child.”

Dr Edith Weisberg

Director Research

Family Planning NSW

As recently as 1905, President Theodore

Roosevelt attacked birth control and condemned

the tendency towards smaller families as “decadent,

a sign of moral disease”. Most countries passed

anti-contraception laws at some time and many

were not repealed until the mid 1900s. Initially both

the Anglican and Catholic churches opposed birth

control. But by 1930, the Anglican bishops had

approved the use of contraceptives for clearly felt

moral obligations to limit or avoid parenthood or

for avoiding complete abstinence. The Catholic

Church officially still only condones the use of

periodic abstinence. Until the 1960’s the word

“contraception” was not allowed to be used on

Australian radio.

Contraception Today

The present generations of women in their

reproductive years find it difficult to contemplate

what life was like for women without access to

modern contraceptive methods. The advent of

the oral contraceptive pill for the first time

enabled women to reliably control their fertility

with a method unrelated to intercourse. The first

pill, Enovid, released in the US on 11th May

1960, contained high levels of the oestrogen,

mestranol (150µg) and the progestogen,

norethynodrel (9.58mg). High doses were used as

there was no information on which to base the

minimal effective dose. The initial high doses

resulted in unpleasant side effects for some

women, such as breast tenderness and

bloating. It was associated with serious health

risks such as raised blood pressure, heart attack

and venous thrombosis.

In Australia the Pill, released in 1961, was

expensive as there was a 27.5% luxury tax

added, which was only removed in 1972 by

the Whitlam government.

Contraceptive choices

The modern woman now has the choice of

many other safe effective contraceptive options.

The development of long-acting methods,

which no longer require daily action on the part

of the user, have increased efficacy to a level

similar to sterilisation. For women who cannot

tolerate oestrogen or have medical

contraindications to its use, the progestogenonly methods offer a number of options ranging

from a daily pill, three monthly injections, an

under the skin implant lasting three years or an

intrauterine system lasting five years. The major

disadvantage of progestogen only methods is

an unpredictable effect on menstruation.

However, the majority of users of these

methods, apart from the Pill, will have either

no bleeding or light irregular bleeding.

For women who prefer regular cycles but

want a longer acting method the low dose

contraceptive vaginal ring that is left in place

for three weeks is available. In some countries,

a skin patch is available which releases

both oestrogen and progestogen and is

changed weekly.

Page 14 | Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l

For women who do not want to use hormonal

methods, copper IUDs provide effective

contraception lasting 5 to 10 years, but may

increase the volume or duration of menstrual

bleeding in some women. An alternative is the

vaginal diaphragm which can provide effective

contraception if used meticulously with each

intercourse. The condom has the added

advantage of protecting against both pregnancy

and sexually transmitted infection.

For women who have completed their families

sterilisation of either themselves or their partner

is an option. Modern surgical techniques

provide minimally invasive outpatient or day-only

procedures for both sexes.

Has the Pill made a difference?

The advent of the Pill, followed by

a plethora of other highly effective

contraceptive methods, has changed

the lives of women and indeed of the

whole community. Gone are the days

where women, especially poor women,

worn out by constant child bearing lived

in fear of pregnancy and often subjected

themselves to unsafe abortion with its

risk of infection, infertility and even death.

With the introduction of the Pill, women

could reliably control their fertility and

their lives were no longer controlled by

their reproductive potential.

Modern contraception has given women the

potential to plan their lives, complete their

education, and make career decisions.

Motherhood is an option to be exercised not

a compulsion. Pregnancies can be planned

and adequately spaced, improving the health

of both mother and child. Limiting family size

enables each child to be provided with

adequate nutrition, education and care

allowing development to its full capacity.

The ability to effectively control fertility has

had a profound effect on western society.

In the majority of relationships sex is a

recreational not a procreational activity, equally

to be enjoyed by both sexes. Women are able

to express their sexuality and enjoy it without

fear of pregnancy. Relationships have changed

drastically since the pre-Pill era where women

were expected to marry young, have children

and become stay at home housewives and

mothers. Moral perceptions have changed.

Premarital sex is accepted and expected;

marriage is no longer the gold standard.

De-facto relationships are common even

when children are involved. There is no stigma

in being an unmarried mother, indeed the state

offers support to single mothers. Women can

choose not to have children and still have

satisfying sexual relationships.

However, as with everything in life there are

down sides to having choices. The modern

woman faces many dilemmas and stresses not

experienced by women in pre-Pill eras. How to

balance career needs with the desire for children.

If she has children, balancing work, home and

child needs while still allowing some time for

recreation and her relationship with her partner.

The biggest dilemma is when to start a family.

Having the ability to control fertility at will has

led women to believe that they can also become

pregnant at will. They expect that as soon as

they stop contraception pregnancy will

immediately follow. Hormonal contraceptives

apart from depot medroxyprogesterone acetate

(DMPA) do not delay the return of fertility.

Irrespective of former hormonal contraceptive

use, it normally takes up to six months for the

majority of couples (70%) to produce a

pregnancy and up to 12 months to two years

for the remainder to conceive. The time to

conception increases with age as fertility starts

to decline in women from 35 years of age.

Modern contraception can prevent

childbearing by young adolescent women

who are likely to suffer more complications

than older women. However, it can make

the decision about when to have a child

more difficult for older women, who may

delay pregnancy because of career needs,

financial needs or find it difficult to accept

the change in lifestyle required once they

have a child.

Future Contraception

Despite the improvements and advancements in

contraception over the last 50 years we still do

not have an ideal contraceptive which is cheap,

100% effective, easily reversible, has no side

effects or health risks and requires little or no

medical intervention.

This holy grail is probably unattainable but

the research continues especially into male

contraception. Although a male pill is highly

unlikely, under the skin implants, injections,

or combinations of the two are likely within

the next five years. These will contain similar

progestogens to those used in female

contraception accompanied by replacement

testosterone. How acceptable these methods

will be to either sex remains to be seen.

Exploration of this issue in a number of different

cultures suggests that it will be high in some

groups but with wide variability, determined by a

number of factors including cultural background

and current contraceptive usage.

Contraceptive vaccines have been researched

for many years but as yet, no successful readily

reversible vaccine has been developed but may

be available in the future.

Compounds which are effective microbicides

as well as spermicides are being researched

which will act as effective local vaginal

contraceptives and prevent sexually

transmissible infections such as HIV,

chlamydia and herpes. Better one-size fits

all diaphragms will enable over the counter

purchase, decreasing cost by avoiding

medical consultation. The development of

long-acting biodegradable contraceptive

implants will mean that users will require only

an insertion procedure but these may pose

difficulty if removal is necessary before the

expiration of the device.

Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l | Page 15

There is an increasing tendency for women

to want bleed-free contraception. This can

already be provided by back-to-back oral,

vaginal ring or skin patch combined hormonal

methods. However, there is a need to find more

effective oestrogen/progestogen combinations,

which result in a stable uterine lining to prevent

the occasional erratic bleeding episodes,

which occur with back-to-back use of

existing methods.

Public policy

Australia has always had a pro-natalist

government policy. Following the post World

War II baby boom, fertility rates dropped below

replacement levels in 1976, reaching a level of

1.75 in 2003, leading to concerns about a

shrinking workforce and a rapidly aging

population. This led in 2004 to the introduction

of a baby bonus of $3,000 per new child,

gradually increasing to $5,000 per child in 2008.

These payments were not means tested until

2009 when families with an income of more

than $150,000 a year were excluded and

instead of a lump sum, the payments were

made in thirteen bi-weekly payments. It is

likely that the baby bonus has in part been

responsible for the increase in the birth rate

from 1.72 in 2003/4 to 1.98 in the financial year

2008/9. However, it remains to be seen whether

the changes made in 2009 to the baby bonus

will sustain this increase.

There is insufficient public discussion

about options for enabling women to

fulfill both their maternal and work goals.

These include better access to affordable

childcare, adequate paid maternity leave,

flexible working hours which are

compatible with family needs and setting up

systems which allow women to temporarily

leave the workforce and return without loss

of career opportunities.

Although overall Australian women have good

access to a variety of fertility control methods,

there is still inequity. The pharmaceutical

benefits scheme (PBS) provides a range of

subsidised contraceptive methods such as pills,

implants and the intrauterine system. However,

poorer women may not have the same choices

as wealthier women. The only pills subsidised by

the PBS are the early second-generation pills.

The newer pills, the contraceptive vaginal ring

and emergency contraception are not

subsidised and may well be beyond the means

of women with healthcare cards, limiting their

choices in finding a suitable method.

Abortion is still within the criminal law in

many states with the present threat of

court action under the criminal code for

both doctors and women. It is time that

abortion is decrimalised and treated as the

medical procedure it is. This would allow

women to discuss the pros and cons

relating to their personal situation and

provide informed consent for abortion as is

the case for any other medical procedure.

A global view Although in Australia, there are inequities in

access to some contraceptive methods these

pale into insignificance when the plight of

women in the developing world is considered.

About 50% of conceptions worldwide are

unplanned and about 25% unwanted. It is

estimated that 300 million couples do not

have access to family planning services.

The unmet need for contraception is estimated

at 17% of currently married women with no

figures on the need of unmarried women.

In developing countries 137 million women

would like to stop childbearing or space their

next birth, but are not using a modern

contraceptive method because they lack access

to information, education, counselling on family

planning, and cannot access services, or face

other social, economic, or cultural barriers.

At the 1994, International Conference on

Population and Development in Cairo there was a

commitment to ensure reproductive health and

health rights for all, including family planning and

sexual health. The wealthy countries pledged

major investments in family planning, sexual

health, safe motherhood and child survival

programs. However, these wealthy countries

and most notably the United States have

provided less than half the amount promised

in Cairo. The United Nations Commission on

Population and Development stated in 2005

that funding for family planning services

decreased in absolute dollar amounts from

$723 million in 1995 to $461 million in 2003,

a decrease of 36%. The Alan Guttmacher

Institute estimates that to meet at a minimum

the ICPD commitments USD 20.5 billion is

required in 2010 and USD 21.7 billion in 2015.

Worldwide, 800,000 women die from

complications of pregnancy and childbirth

annually, all but 4,000 of whom are in the

developing world. This is more than four times

the death toll of the Aceh tsunami. For every

woman that dies up to 10 more women will

have significant morbidity. Many of these

complications last her lifetime. In Australia,

women have a lifetime risk of 1 in 6,500 of dying

of a pregnancy related cause but the risk is five

times greater for indigenous women. Eastern

and Southern African women have a 1 in 15 risk

while in South Asia the risk is 1 in 43. One

quarter to one third of maternal deaths in

the world are due to complications of

unsafe abortion. Of the 150,000 pregnancies

terminated daily one third are done in unsafe,

adverse conditions.

Among the millennium goals set in 2000 to

be achieved by 2015 were the eradication

of poverty and hunger, promoting gender

equality, reducing child mortality and

improving maternal health while also

ensuring environmental sustainability.

At the time, no mention was made of the

obvious link between these goals and

reproductive and sexual health.

To achieve goal 5, improving maternal

health, contraceptive services are needed

to effectively save lives by preventing

unplanned and high-risk pregnancies.

Averting unwanted pregnancies will also avert

unsafe abortions. Emergency obstetric care and

pre and post-natal care are critical to safe

motherhood. Preventing high-risk pregnancies and

providing pre-natal care reduces infant and child

mortality. Smaller families and better birth spacing

allow families to provide better nutrition and health

care. Unwanted pregnancies can put infants and

children at risk of neglect or abandonment.

Page 16 | Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l

To achieve goal 3, the promotion of

gender equality, controlling the timing

of childbearing is critical to women’s

empowerment, including educational

attainment and paid employment.

Smaller families may reduce gender inequities

in nutrition, education, health care and other

family investments in children.

To achieve the goal of environmentally

sustainable and equitable development,

delayed childbearing, wider birth intervals

and smaller families are necessary to slow the

momentum of population growth. Control over

childbearing can also help families emerge from

poverty. Lower fertility levels can permit higher

per capita investments.

Meeting global family planning needs will

save the lives of an additional 1.5 million women

and children each year, reduce the number of

induced abortions by 64% by averting 52 million

pregnancies, preventing 142,000 pregnancy

related deaths (including 53,000 from unsafe

abortion) and preventing 505,000 new orphans.

The transformation of reproductive and

sexual rights and health into reality requires

political will, increased and sustained

national and international financing for

reproductive and basic health services.

There needs to be equality and adherence to

human rights which encompass advocacy for

reproductive rights. There is a need for

intersectorial action nationally and internationally

to link progress in the development of health,

education, poverty alleviation and human rights.

Conclusion

While western women celebrate 50 years

of the Pill and the freedoms they have achieved

through effective fertility control, even if gender

equality is not yet fully achieved, we need to be

aware how fortunate we are. For the most part,

we have a range of affordable contraceptives,

excellent sexual and reproductive health

services and maternal and childcare facilities.

We should not take this for granted but work

towards a worldwide recognition that access

to reproductive and sexual health and related

services are a human right.

Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l | Page 17

A REFLEC TION: Pills, sex a n d fam i ly pl a n n i n g …

“It would be wonderful if sexually active young

people could all confidently access services and

receive comprehensive and accurate information

at school as well as via new avenues such as

the internet and social media. But this is not of

course always the case, particularly in our rural

and remote areas, and amongst Aboriginal and

migrant women.”

Dr Deborah Bateson

Medical Director

Family Planning NSW

When invited to write these short reflections,

I could not help thinking back to my own first

contraceptive experience. As a teenager,

growing up in Liverpool in the UK in the mid

70s, I experienced a serious pregnancy scare

just before my A-level exams.

Luckily my mother and I could talk about such

things and, after the scare proved unfounded,

she decided that a visit to the family GP was

in order. He was a kind, and in hindsight,

enlightened doctor and I can remember every

detail of the consultation in which we all

enthusiastically agreed that the Pill would be

terribly useful for my “menstrual migraines” and

never once mentioned the word contraception

let alone anything to do with boys or sex.

Everyone was satisfied with this solution and

I was able to get through those exams and go

off to university with control over my fertility. It

would be wonderful if, 30 years later, sexually

active young people could all confidently access

services and receive comprehensive and

accurate information at school as well as via

new avenues such as the internet and social

media. But this is not of course always the case,

particularly in our rural and remote areas, and

amongst Aboriginal and migrant women.

Women’s Suffrage.

Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l | Page 19

t h e pill i s 5 0 years old …

“The Pill is 50 years old – but has it fulfilled

our expectations? Where have we come with

contraception and family planning in the last

half a century?”

Professor Gab Kovacs AM, MB, BS HONS, MD.,

FRCOG, FRANZCOG, CREI, FAICD, Grad Dip Mgt (Macq)

Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Monash University.

Honorary Consultant, Family Planning Victoria

The medical evolution of the modern pill

In 1949 Carl Djerassi joined Syntex, and with

his colleagues prepared norethisterone from

19-nor-testosterone in 1951. This had twice

the potency of progesterone,1 and in contrast

to progesterone which had to be administered

parenterally, it was orally active. This was the

first of several ethinylated testosterone derivates

which have been used in oral contraceptives.

In the USA it is known as norethindrone, and

the rest of world knows it as norethisterone.

This new progestin was first tested clinically

for the treatment of menstrual disorders by

Dr. Hertz at the NIH at Bethesda, USA in 1954.

Simultaneously, Dr Frank Cotton at G D Searle

patented another synthetic progestin,

norethynodrel, which was astonishingly similar

to norethisterone, the only difference being one

double bond between two of the carbon atoms.

Yet they were synthesised by different methods

and slightly different biological actions.

Although it had been recognised since the 1940s

that ovulation could be mostly inhibited by the

administration of oestrogen the addition of oral

progestin resulted in better efficacy and cycle

control. It was Rock, Garcia and Pincus who

found that the potent new progestin

norethynodrel at 30mg per day, administered

from day 5 to 25 of the cycle was an effective

contraceptive.2 These findings were first

presented at an International Planned Parenthood

Federation meeting in Tokyo in October 1955.3

Field trials were established in Puerto Rico, using

the Searle product norethynodrel.

It was believed that only the progestin was

necessary for contraception, and the “impurity”

oestrogen was eventually removed by the Searle

chemists. This led to a loss of cycle control and

decreased efficacy. It then became recognized

that oestrogen was necessary, and was

reintroduced in precise amounts.

The first oral contraceptive

These studies led to the approval of the first oral

contraceptive, Enovid (Searle, USA) in 1959.

Enovid contained 9.58mg of norethynodrel and

150ug of the synthetic oestrogen, mestranol.

The first oral contraceptive on the European

market was Anovlar (Schering, Germany).

This contained 4mg of nor-ethisterone as

the progestin, and 0.05mg of ethinyl oestradiol

in 1961.

Soon a more potent progestin, norgestrel was

developed, requiring only 0.5mg to be effective,

compared to 10-15mg norethindrone. It became

known as a “second generation” progestin.

When first introduced, norgesterel was a mixture

of the d and l isomers, and it subsequently

became recognised that the pharmacological

activity was exclusively from its levo form.

Page 20 | Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l

the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS),

they never captured significant market share

in Australia.

The next phase

What I call the “fourth generation” progestin

is drospirenone, a progestin derived from

17a-spirolactone with a pharmacological profile

similar to that of natural progesterone with potent

progestogenic, anti-mineralocorticoid, and

anti-androgenic activities and no oestrogenic

activity. It is available in Yasmin® and Yaz®.

One must not forget the cyproterone acetate/

ethinyl oestradiol containing oral contraceptive

which in Australia is approved for use in the

treatment of acne and “not indicated for

contraception alone.”

Dr Gregory Pincus.

In order to reduce the dose of progestin

further, its active levo-isomer was isolated

and subsequently used as levo-norgestrel,

without affecting efficacy.

Third generation pills

The next phase in the development of

progestins in oral contraceptives was the

development of a novel group of gonane

progestins with minimal androgenic activity.

These are called the “third generation”

progestins, and include desogestrel (active

metabolite 3-keto-desogestrel), gestodene and

norgestimate. The former two are now readily

available in oral contraceptives. These

preparations combine high progestogenic

efficacy with low androgenic activity.4

Unfortunately, combined oral contraceptives

(COC) utilising these third generation

progestogens were caught up in the Venous

Thrombo Embolism (VTE) controversy of 1995.5

Consequently, and as they were not listed on

Nevertheless, it is an efficient contraceptive,

and is the COC of choice for women with

androgenic symptoms, and many women

with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

The oestrogen component

The only oestrogens used in a COC for the

past 50 years were either ethynyloestradiol (EE) or

mestranol – which is metabolised to EE. We went

through the fight to have “natural” oestrogens used

in Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) on the

PBS because they had fewer side effects, and we

have waited 50 years to have COC containing a

natural oestrogen rather than EE. We now have a

natural oestrogen containing COC on the market,

Qlaira®, an oral contraceptive with four sequential

phases comprising differing levels of the oestrogen,

estradiol valerate, and the progestogen, dienogest,

in a oestrogen step-down and progestogen

step-up regimen.6

Next year another natural oestrogen pill

containing 17b-oestradiol, with nomegestrol

acetate as the progestogen in a monophasic

preparation will be available in Australia.

Phasic pills

Although the initial pill preparations contained

the same concentration of oestrogen and

progestogen, in the early 1980s it was

recognised that the dose of hormone could

be reduced if they were administered in a

sequential step up manner, where the progestin

dose increases from 50ug per day to 125ug per

day.7 The triphasic preparation resulted in a 39%

reduction in the dose of levonorgestrel ingested

each month. By minimising the amount of

levonorgestrel, the triphasic preparation was

found to increase Sex Hormone Binding

Globulin (SHBG), and did not change HDL

cholesterol, and had less effect on HDL

cholesterol: total cholesterol ratio than the

monophasic version, and in summary has less

negative effects on lipid metabolism.8 Though

initially popular, it was soon recognised that its

disadvantages outweighed its benefits.

Duration of pill taking

When the Pill was first released it was marketed

on a 21 days of hormones, 7 days pill free

regimen, as a marketing ploy, so that every

woman who took it would be a “perfect 28 day

woman”. There is absolutely no physiological

reason for this, and it could have easily been

a six weekly or three monthly cycle. The

“trimonthly regimen” was piloted in Australia

in 1994, with the only disadvantage being an

increased incidence of break through bleeding.9

It was subsequently marketed in the USA

as “Seasonale®” a 30ug EE and 150ug

levonorgestrel pill, packaged as 84 active tablets

followed by 7 placebos. It again was reported to

have less bleeding days, but more unscheduled

bleeding. In 2007 the US FDA approved Lybrel®,

a continuous combined oral contraceptive pill

containing 20ug of EE and 90ug of levonorgestrel.

Non-contraceptive benefits of the Pill

Quality of life: one of the greatest noncontraceptive benefits of the combined oral

contraceptive pill is the relief of dysmenorrhoea

or painful periods. This is thought to be due to

the inhibition of ovulation and the absence of

a corpus luteum. The corollary of this is that if

dysmenorrhoea persists despite the use of

the Pill, then a pathological cause such as

endometriosis should be considered.

Another non contraceptive benefit of highly

significant proportions is the decrease in

menstrual blood flow with consequent

decrease in the incidence of anaemia.

Not only does the Pill decrease menstrual loss,

but it gives a woman the ability to control when

she menstruates.

Longevity: research in which the “chance of

dying” among women who have ever used oral

contraceptives was compared to that of never

users. This prospective cohort study started in

1968 and 46,112 women were observed for up

to 39 years, resulting in 378,006 woman years

of observation among never users of oral

contraception and 819,175 among ever users.

It was reported that ever users of oral

contraception had a significantly lower rate of

death from any cause (adjusted relative risk

0.88, 95% confidence interval 0.82 to 0.93) with

an estimated absolute reduction in all causes of

mortality among ever users of oral contraception

of 52 per 100 000 woman years.10

Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l | Page 21

Cancers and the Pill

There is unequivocal evidence that both

ovarian and endometrial cancers are significantly

decreased in current and past users of the COC.

The incidence of cervical cancer is difficult to

assess because of confounding factors of condom

use, number of partners, sexual activity and HPV

incidence, but current studies do show that there

may be a slight increase.11 The studies on the

incidence of breast cancer are conflicting, and

the results are confounded by individual risk

factors, including genetic predisposition.

When combined in a meta-analysis they show

a significant but modest increased risk of

premenopausal breast cancer in general (OR,

1.19; 95% CI, 1.09-1.29) and across various

patterns of OC use, especially with use before

first full term pregnancy in parous women.12

Venous thromboembolism and the Pill

Although the COC was only released on the

market in 1960, by 1961 the first report of a

thrombo-embolic complication was published.

It was recognised that the risk was related to

the oestrogen dose, and there has since been

a steady decrease in the oestrogen dose from

150ug to as low as 15ug. There also has been

much discussion about the degree of risk, and

the possible increased risk with various

progestogens, especially the “third generation”.

Some thoughts 50 years on…

The population explosion

One of the world’s greatest problems is

conservation – how can we feed, house and

supply water for the exploding population

especially in developing countries?

On a worldwide basis we have made great

progress with the birth rate steadily decreasing:

Table 1. Change in birth rates 2003-2004.14

Percent

Change

Date of

Information

Year

Birth rate*

2003

20.43

2004

20.30

-0.64 %

2004 est.

2005

20.15

-0.74 %

2005 est.

2006

20.05

-0.50 %

2006 est.

2007

20.09

0.20 %

2007 est.

2008

20.18

0.45 %

2008 est.

2009

19.95

-1.14 %

2009 est.

2010

19.86

-0.45 %

2009 est.

2003 est.

* The average annual number of births during a year per 1,000

persons in the population at midyear; also known as crude birth

rate. The birth rate is usually the dominant factor in determining

the rate of population growth. It depends on both the level of

fertility and the age structure of the population.

The average child per couple worldwide is

now at a weighted average of 2.8 children

born per woman, with an average of 1.5 for

the European Union.

There is still a disproportion in developing

countries with 7.34 born per woman in Mali,

and 7.29 in Niger, 6.58 in Afghanistan.

However countries like India have reduced

their population growth to 2.76 and China

to 1.77 per woman, due to population

control measures.14

Thus on a global level population control

has made a difference.

Unplanned pregnancies

Unfortunately the advances in contraception

have had little effect on the number of

unplanned pregnancies in most developed

countries. It is reported that one in 10 Dutch

women has had a termination of pregnancy.

Firm data for Australian women is not available,

but statistics from Britain for 2009 record

189,100 abortions.

Figure 1. United States abortion rates,

1960-2005.15

There is no doubt that all COC are associated

with an increased incidence of venous thromboembolic (VTE) events, but overall VTE is a rare

event, so whilst being statistically significant,

is it clinically significant? Dinger illustrates this

elegantly in his research showing that the risk

of VTE in non-pregnant women not using any

oestrogen containing COC is 4.4/10,000 woman

years, those using low dose pills is 8.9/10,000

and during pregnancy 29.5/10,000.13

Why are we still having an epidemic of

unplanned pregnancies when there are

so many contraceptive choices?

Barriers to obtaining contraceptive advice

In 1970, my “engaged” but not yet married

sister in law attended a General Practitioner

for a repeat prescription of the combined

contraceptive pill. He threw her out after giving

her a lecture on “pre-marital” sex. I would be

very surprised if that would still happen today,

and there are many facilities for young single

women to obtain contraceptives, such as family

planning clinics, student health centres and

teenager friendly practices. Condoms are

available not only in supermarkets but also

from vending machines, so accessibility of

contraceptives is not a problem. Many oral

contraceptives are subsidised by the

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and available

to socially disadvantaged women on a Health

Care Card for $5.30 a prescription, which

includes the etonogestrel implant (Implanon®)

for three years of contraception, and the

levonorgestrel intrauterine system (Mirena®)

for five years of protection.

Some couples have unprotected intercourse

because they think that “it won’t happen to

them”. Just once can’t possibly get them

pregnant, or they just decide to risk take,

especially if under the influence of alcohol

or drugs.

We must continue to educate that once is

enough, and also make condoms readily

available. It is good to see vending machines

in hotels, clubs and airports. We must also keep

re-enforcing the message that a well applied

condom properly used is an effective

contraceptive, as well as being a reasonable

barrier to most sexually transmitted infections.

It is hard to determine what proportion of these

were unplanned, but one can presume, most.

Page 22 | Ta k i n g i t – 5 0 y e a r s o f t h e p i l l

Barriers to the effective use of contraceptives,

especially the Pill.

When considering the effectiveness of any

contraceptive there are three levels of efficacy:

1. Perfect use or theoretical efficacy; using

the method correctly and consistently (this is

quoted at less than 0.55% for 30ug pills and

up to 1.26% for 20mcg pills.)16

2. Typical use; the efficacy one would expect

from actual users in a clinical trial who follow

all instructions. This is quoted at up to

1.19% for 30mcg and up to 1.6% for

20ug pills.16

3. Imperfect use – which is also described

as “patient failure” where users do not

follow the instructions. The Pearl Index

for imperfect use is unlimited.

With oral contraceptives there is great

opportunity for imperfect use, forgetting to

take the tablets every day, taking it later than

the twenty-four hour rule permits, or not

following the “seven day rule” after an

indiscretion. There is also the possibility that

there has been some interaction resulting in

malabsorption, or large bowel reabsorption,

such as vomiting, diarrhoea or drug interactions

inducing liver enzymes or interfering with

steroid reabsorption.

The non-oral administration of combined

oestrogen:progestogen overcomes some

of these possible risks for “imperfect use”,

an example being the contraceptive vaginal

ring (NuvaRing®).

The efficacy of hormonal contraceptives has