The National Association of Publicly Traded Partnerships

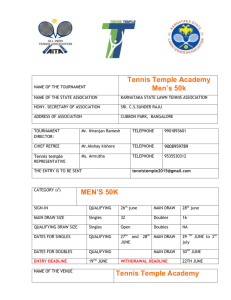

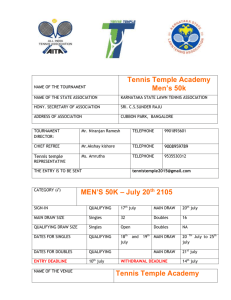

advertisement