The Hard Bard and The Bacchae Synopsis Who Were the Bacchae?

advertisement

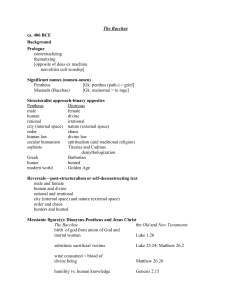

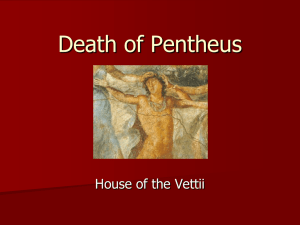

GreenStage 2013 Bacchae, Web Site Copy By Jeffrey Thomas The Hard Bard and The Bacchae With the gruesome ends to which characters come in The Bacchae, the play and Hard Bard are a match made in…a charnel house. The idea of the Hard Bard is to stay true to the text, while looking at it through a fisheye lens, making a play’s excesses more excessive—blood and violence!—the front row is an official Splash Zone, after all. But the purpose in the Hard Bard madness is to bring out the play’s inner th dynamics. Like a 19 -century grave robber digging up corpses for illegal medical research, the Hard Bard brings the story’s buried structure to the surface. In classical Greek tragedies, all the violence took place off-stage, and was reported by a messenger character such as the Herdsman in The Bacchae. In the Hard Bard, the Herdsman still reports news of the slaughter on the mountain, but at the same time, we’ll see it on stage. Although this certainly violates a convention of the tragedies, bringing the violence on stage sends the sparagmos at the heart of the story leaping (with the blood) across our habitual distance as an audience, and demanding our instant, gut participation. The Hard Bard’s approach is spectacularly apropos to The Bacchae. The climactic image, which will leave many open-mouthed with horror as it twists the most fundamental human relationship more perversely than the blackest of today’s dramas dare, also resolves the play’s central concern: What we see and how we see. Synopsis Hey, kids! Let’s become Bacchae and worship Dionysos, the god of wine, religious ecstasy, harmony with nature—and sparagmos and omophagia. What are sparagmos and omophagia? Why, sparagmos is the tearing of a god, animal, or human limb from limb. And omophagia is eating the torn body raw. When we Bacchae are in a religious frenzy, this is our idea of good clean fun. Dionysos is the son of the god Zeus and a mortal, Semele, a member of Thebes’ ruling family. But like prophets, even gods may not be respected in their home town. Semele’s sisters—Dionysos’ own aunts!— put about the rumor that Dionysos’ father wasn’t a god, but an ordinary mortal. To add injury to insult, Pentheus, ruler of Thebes and Dionysos’ cousin, has been suppressing the Bacchae’s worship of Dionysos. The god, who has been spreading his religion across Asia Minor and the Balkans, comes back home to set things right, and he’s no Emily Post. Pentheus is sure that the Bacchae’s worship outside of town on Mt Kithairon is a cover for drunkenness and promiscuity, and as the champion of social and moral order, he plans to send them into jail or slavery. When Dionysos shows up disguised as a mortal, Pentheus throws him in jail, but jail holds a god like Dionysos about as well as a palace stands up to an earthquake. The self-liberated god convinces Pentheus that before attacking the Bacchae, he should dress up as a woman in order to spy on them— and, Pentheus hopes, to catch them rutting in the underbrush. In the catastrophe that Pentheus’ voyeuristic spying mission brings about, everyone admits that Dionysos is a god, but Pentheus’ change of mind comes way too late to avoid tragedy of the most heart-rending—and other-body-parts-rending— kind. Who Were the Bacchae? Also called Bacchantes, they were members of a religious cult that swept over Greece in the 600s BCE, a period of social and political upheaval in Greece, when the social and political units were evolving from individual farming hamlets and families to more-commercial city-states, and a succession of tyrants grabbed power. In this period, the cult of the Bacchantes arose. They were dedicated to Dionysos, a god of fertility, intoxication, and growth. They worshipped him by dancing themselves into a frenzy and tearing up and eating, raw, animals that in such worship sessions was the god incarnate. Who was Dionysos? An attractive, terrifying, disruptive, subversive god (, whose identity and characteristics changed with every community that adopted him, and have continued changing with every age since). Dionysos was the god of grapes, wine making, ritual ecstasy and epiphany. Also known as Bacchus and Bromios, Dionysos is depicted as an androgynous youth holding a fennel staff tipped with pine cones and dripping honey, called a thyrsos. Euripides Euripides, born between 489 and 480 BCE, was, with Aeschylus and Sophocles, one of Greece’s three great tragedians whose works have survived. Despite the loss of many plays by other authors, the work of these three contains greatness. Euripides’ career coincided with Athens’ rise to power and her golden age of philosophy and art that resulted. One tradition has it that he was born on the day of the Battle of Salamis, at which Athens and her allies, tremendously outnumbered, destroyed the fleet of Persian invaders. Euripides’ creative life developed during a century, when his Athens became the strongest of Greek cities through driving off an invasion by Persia. The broad middle of the century was a golden age of great intellectual vitality, when the old ways of relating to the Gods and the mythical construct were changing. Euripides was notable for the impossibility of pinning him down to a single philosophical position. D.W. Lucas, in The Greek Tragic Poets, says that Euripides “can by insight of imagination see the attitudes of others as though they were his own, but he commits himself to none.” As it happens, Lucas considers The Bacchae to be a premier example of this resistance to identification with a single position or school. Form and features of classical Greek tragedy The play has a prologue, followed by alternating episodes and choral interludes. The episodes, which we would call scenes, are those in which individual actors speak and forward the plot. The choral interludes, called stasima (singular: stasimon), separate the episodes. The Messenger The Messenger brings reports of the crucial off-stage action. In our production, we will see the action that the Messenger reports. The Chorus The Chorus rarely comprises human characters that the audience would identify with. They are usually supernatural, partly supernatural, or otherwise removed from commonality with the audience. In The Bacchae, they are Dionysos’ followers from Lydia (in near Asia), which in the eyes of Euripides’ audience was enough to make them exotic, out of the Athenian norm, and therefore suspect. The Athenians regarded people from the east as sexually suspicious too. In The Bacchae this would be enough for the audience to see Dionysos as effeminate and therefore sexually suspect. The Chorus only comment on the action; they do not take an active part in it. (In Medea, they try and fail to batter down a barred door.) As close as they come to the action is to speak to individual actors. This was part of tendency over the course of the great age of tragedy to increasingly marginalize the Chorus. The Epiphany The epiphany is the appearance of a god to humans, in our midst. In The Bacchae, Euripides takes the epiphany into previously unexplored territory: His Dionysos first appears disguised as a human, and spends most of the play in that guise, then is reported as a voice (that we will hear, our epiphany enhanced by the house PA system), before finally appears in his godlike form. Glossary and names Bacchos (Bacchus or Bakkhos) Another name for Dionysos. Bromios Another name that the Bacchant Chorus uses for Dionysos. Evoi Ecstatic cry when worshipping Dionysos with dance. Lydia A kingdom in the western part of Anatolia (which is now modern Turkey). Phrygia A kingdom in the western central part of Anatolia (which is now modern Turkey). Phrygia bordered Lydia on the east. Sparagmos The ritual tearing apart of the body of a god or hero, which carried into tragedies and was brilliantly written into The Bacchae. Stasimon A song sung by the Chorus only, between episodes, when everyone else has left the stage. Thiasoi Bacchantes in a band. Thyrsos (thyrsus) The fennel staff, decorated with ivy, which the thiasoi use in their celebrations, either striking it on the ground or shaking it toward the sky, or as weapons when attacked. Tmolos A mountain in Lydia (in modern Turkey), where the Chorus, as Dionysos’ Asian Bacchae, held their rites, as his Theban Bacchae do on Mt. Kithairon, outside of Thebes. The Bacchae: How we see and what we see To say that many of the problems and potential thrills in The Bacchae have to do with point of view—what we see in the play—may seem a statement of the obvious. The more aspects of a story there are, the more rewarding it is as a work of art: The greatest works, including The Bacchae, have not been tapped dry in thousands of years of criticism, partly because each age finds its own reflection in them. More specifically, The Bacchae, Euripides’ last, play, is a work that is about the problem of what we see and how we perceive. Throughout the play, characters are telling each other that they see things correctly or incorrectly, that they are in their right minds or are right out of their mind, the mental framework that determines who you think you’re dealing with: people or gods—fools or con artists—your mother or a dangerous revolutionary—your child or a wild animal. How ancient Greeks saw dramas How tragedies were staged The issue of how we see the play extends to the world that we bring with us to the performance: the social, civic, and religious context in which tragedies were presented. Tragedies were produced for the Great Dionysia, a festival dedicated to the god Dionysos, who is both hero and villain of our play. The Great Dionysia had been running for more than a century when Euripides wrote The Bacchae. Each year, playwrights submitted a trilogy of tragedies plus a humorous “satyr play” for competition in the Great Dionysia. Between three and five playwrights were selected to compete in the festival; each had a patron (the “choregos”) who funded rehearsals, production, and paid the chorus—so today’s producer or producing organization would be the choregos. The competition between the selected playwrights resulted in ranked placings, because to feel that Nike, or the spirit of victory, was present, there had to be a competition, with a winner. However, all of the competitors, even the playwright who came in last, were awarded prizes. It may seem like childhood games that grownups set up these days, in which no one can lose, but the reason was a little different: It was inauspicious to speak of failure; it could bring bad fortune to the entire community. One thing to keep in mind with this arrangement is that just getting into the festival competition set you apart as one of the very best in the community. The festival’s traditions emphasized its central religious and political significance to the nation. The Theatre of Dionysos was named for and dedicated to the god, had a statue of the god above the highest row of seats. The theatre held 15,000-20,000, but competition for seats was fierce. The city Assembly did not meet during the festival; the jails were opened so that the inmates had a chance to attend; and the government distributed a subsidy called the theorikon that, among its other uses, gave poor people an equal chance at seats. Before the first play of the day, the theatre was ritually purified, then Athens’s ten generals, the very most important of Athens’s elected officials, offered a libation of wine to the gods. Tribute from Athenian allies was paraded out on the orchestra, where the chorus performed. When sons of war dead attained adulthood and were thus old enough for military service, they were presented onstage with suits of armor, and offered seats in the front row. By contrast, when we moderns go to a play, we are attending an entertainment rather than an explicitly political or religious event. Any political or religious overtones or implications come from the content of the play, not from the venue or event in which the play is staged, nor from the institution of the theatre. Apart from the importance of tourism and any economic activity that the theatre business creates, theatregoing, even in a drama festival, has relatively little civic significance in the modern world. Our experience is essentially individual. While it’s possible to identify communities that play-going is part of or creates, such communities are functions of shared recreational interests rather than political forces. Theories of the Birth of Greek Tragedy There are a number of theories for the origins of Greek tragedy; each could affect how we think the Greeks saw them. Note that the first and third theories support emphasis on the religious aspect of the Great Dionysia. That tragedy evolved from the ritual re-enactment of the death, dismemberment and scattering, and rebirth cycle of Dionysos. This cycle of the god reproduced mythically the annual agricultural cycle: growth from seeds, fullness of maturity (which in the Greek worldview necessarily produced excessive pride), death and dismemberment in the generation and scattering of seed, and growth of the seeds in the following year. That the satirical satyr plays existed first, and that the tragedies evolved from those. That tragedies grew out of re-enactment of mythic stories. Sophie Mills, in Euripides: Bacchae, holds that “tragedy dramatizes myths in order to explore fundamental structures and institutions—especially sacrifice, marriage, and agriculture—in Greek society.” In this view, tragedies examine the structures and institutions by dramatizing what happens when they break down or are violated. Mills points out that regarding Dionysos and Pentheus as symbols or as psychological ways of being can reflect our own mental and cultural makeup as an audience rather than that of the ancient Greek audiences. A structuralist approach, on the other hand, may be more rooted in the context in which the plays played, because it tries to look at the role that the tragedies played, the effects that they had, within what we know of the Greek culture of the time. The Ancient Greek audiences and the play Structuralist critics see the play as both enacting and questioning the structures and assumptions of the civic and political order, the religious view, and the conventions of tragedy. Would the ancient Greek audiences sense in the play such questions? A complex view, given the importance of the festival both religiously and civilly. Whatever degree of cynicism, jadedness, and/or disbelief we think audience members may have felt, the tragedies presented and the festival in which they were shown were clearly of central importance, if only symbolically, in the national life of Athens. Seeing the play as providing a critique of its world, the social ways of doing things, assumptions, values, and motivations of Athens and the Athenians both individually and as a nation is tricky, when we consider that if a tragedy did not meet the audience expectations for such dramatic mechanisms as how information was presented, the audience could and did drive the actors and chorus from the stage. This happened even to the greatest tragedians. This could mean that Euripides was carrying off a real high-wire act, really challenging his audience’s view of the patron deity of one of their most major festivals by portraying the god as vengeful and oppressive. However, the Greek gods were not morally superior, in our sense, to humans. Many of the mythic stories require their deities to be vengeful and have other qualities that are reprehensible by modern standards. Thus the audience would not necessarily react badly to Dionysos’ manipulation of Pentheus or to his extreme cruelty his punishment of the entire clan of Kadmos. The ancients’ view of Dionysos To the audience, Dionysos may have been a bundle of contradictions: He came from Greece, yet the cult of worshiping him came from, as Charles Segal describes it in Dionysiac Poetics and Euripides’ Bacchae, “barbarian Asia, escorted by a band of wild Asian women,” his Bacchantes. (Another historian notes that the Greeks equated Asia with effeminacy.) Having a divine father and a mortal mother, Dionysos is human, yet a god; a god, yet human. Dionysos is male, yet had features that the Greeks considered effeminate. His ambiguity extends to his birth, in which Zeus not only was his father but also provided his womb. The Roman poet Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, tells us how: When Zeus slept with Agenor’s daughter Europa, who is also Kadmos’ brother, Hera wanted revenge on the entire house of Agenor. To make things worse, Zeus also got Europa’s niece Semele pregnant (with Dionysos). Hera tricked Semele into asking Zeus to prove he was a god and not just a mortal cad by coming to her as he came to Hera. He came to Hera, it seems, in his lightning-bolt form. Semele couldn’t take back her request, and Zeus couldn’t take back his promise, so his next visit, as a lightning bolt, killed the pregnant Semele. Zeus rescued her fetus, Dionysos, sewing him into his thigh, which was thus Dionysos’ womb until Dionysos came to term and Zeus gave birth to him. (After Dionysos was born, his aunt Ino cared for him in his crib. In The Bacchae, we will meet her as one of Dionysos’ Theban worshippers.) In being devoted to Dionysos, his followers—who in the play are nearly all women—had an idyllic relation with nature, a vacation from daily life on the slopes of Mount Kithairon outside the city. Yet in this idyll, they neglected their domestic duties, o far that nursing mothers left their children behind, suckling instead wild animals—even young wolves, which the audience surely regarded as whelps who can grow up to be potential killers of humans. Further, their pastoral gatherings could turn into a killing ground in moments as Dionysos whipped them into a murderous, destructive frenzy that gave them superhuman strength. Would the audiences feel that the excessive and almost flamboyantly perverse violence of Dionysos’ punishment of Kadmos’ clan (the Kadmeians) was justified by the fact that Pentheus and his mother and aunts refused to give Dionysos his due? Excessive punishment of those who fail to worship the gods or who act against divine will or fate is a staple of Greek myths and the tragedies based on them. In the Dionysos stories, it is a convention that the doubter converts too late to avoid a deadly punishment. Thus Euripides created a Dionysos and a version of Dionysos worship that contained contradictions, about whom the audiences at the Great Dionysia would have severely mixed feelings and judgments. The ancients’ view of Pentheus Similarly, audiences could have felt mixed about whether Pentheus deserves what happens to him. On the one hand, Pentheus defends Thebes against an interloper who takes women away from their domestic duties. In Pentheus’ eyes and those of Athenians in his position, the Stranger who is Dionysos in human form might well be a charlatan, a false leader who propels his followers through mindless frenzy to terrifying excesses. Seaford notes in his commentary on The Bacchae that Dionysos would appear to playgoers like “those promoters of new cult” in origin-explaining myth, “as well as the generally disreputable purveyors of mysteries in Athens in the classical period.” So Pentheus’ suspicions of Dionysos as a fraud and bad influence would be quite creditable to the audience. On the other hand, Pentheus may be a great example of what “hubris” meant to the Greeks. “Hubris” is more than excessive pride. The ancient conception of hubris meant having an excess of not just pride (as we understand it), but any single quality or drive that causes one to get athwart of the will of the gods, and to thereby bring catastrophe on oneself. Pentheus is so much the ruler of his city and defender of order that he cannot see the manifest divinity in front of him. It is clear to the audience that the Stranger whom Pentheus contests with and attempts to imprison is Dionysos himself. Pentheus is either too dense, too obstinate, or too committed to his vision as protector of the city to see who the Stranger is. His opposition to the Bacchantes is so determined that he insists that they are out on Mount Kithairon to get drunk and have sex in the bushes despite repeated reports of the innocence of their pastimes. Pentheus could be a sexually and otherwise repressed hypocrite and voyeur, who, we are tempted to think, insists against factual reports on the depravity of the Bacchantes because such sexual license and drunkenness are the stuff of his own fantasies. Once Dionysos, simply for the purpose of gratuitously humiliating Pentheus and destroying him as Thebes’ leader, persuades Pentheus to wear a woman’s robe, Pentheus might get a kick out of the activity that he dislikes and disapproves of. G.M.A. Grube, in The Drama of Euripides, thinks that Dionysos “alone of all the characters, possesses that dual nature, than inner conflict that we usually find in the chief characters of great tragedy, not least in Euripides…he is the god of a joyful worship, the friend of mortals; he brings rest from care, happiness, ecstasy; yet he is also cruel, ruthless, cunning, a very fiend.” Grube goes on to argue that rather than the tragic conflict arising from the opposition of a human to a god, or to fate, in The Bacchae, “it arises from a conflict within the nature of the god himself.” However, Pentheus’ actions suggest a profound split within him, too. It’s just that one of his conflicting sides is buried beneath his consciousness. Or is that a modern psychological concept, and not something that the Greeks would recognize? When Pentheus is concerned about his woman’s robe hanging correctly, is it just a concern with doing a thing correctly, no matter what that thing might be, rather than the revealing of a repressed enjoyment of cross-dressing? On the play’s language Self-contradictions begin in the Chorus’s first song (stasimon). How much do subtleties of language come across to an audience? The author certainly intends them, but how much does audience get? On the page, the reader may linger over and reread them, or even turn back the page and revisit them. In performance, the audience has to absorb a story that is flying by in real time. How many of the contradictions and other linguistic subtleties streaming out from the stage do audience members snatch out of the air? Modern audiences and the play If our interest is primarily historical, then we’re more concerned with how the Greeks saw The Bacchae and the other tragedies of the Great Dionysia. This historical emphasis typifies much criticism, such as the analysis that concerns itself with how the play critiques the Greeks’ myths and the social assumptions, values, and rules that grow out of them. A number of interpretations of what the play might mean to us also aim at what the Greeks might have seen in the play. Others focus on various oppositions centered on the two antagonists, Dionysos and Pentheus: Freedom vs. restriction: Dionysos liberates, temporarily, women from their mundane daily responsibilities and sends them out running around on Mt. Kithairon, in pastoral harmony with nature—at least, when they aren’t ripping up old-growth by the roots or tearing live animals to pieces barehanded. Pentheus responds to Dionysos’ and the Bacchae’s challenges to him with chains and imprisonment. Sensuality vs. Pentheus’ seeming antipathy to sexuality. Self-transcending rapture and the fine frenzy of poetic vision vs. rationality, pragmatism, and conventionalism. Belief in deities vs. atheism. Our modern approach is not concerned, however, with literal belief in the ancient Greek gods. The interpretations that focus on these oppositions often concern themselves with whether Dionysos or Pentheus is the good guy. Some modern views of the play’s Dionysos One of the touch points for describing Dionysos in modern criticism is as the god who spans and tumbles boundaries. This set of qualities may go beyond Grube’s description of the god’s dual nature. Segal notes that Dionysos (outside the play) is the center of the city’s very formal religion, “yet his worship involves ecstatic flaming torches on the mountains.” In addition, there are the boundary-crossing contradictions mentioned above. Segal continues, “He crosses the class division within society, offering his gift of wine as an ‘equal joy’ to both rich and poor.” That, “both a native by birth and a violently resisted intruder, [Dionysos] honors Thebes and threatens its destruction.” In one of the most important self-contradictions, Sophie Mills (Euripides: Bacchae) paraphrases another critic’s defense of Dionysos and his religion as bringing his believers “emotional release, peace, and unity with fellow worshippers and with the natural world.” She then notes on the other hand R.P. WinningtonIngram’s recognition (in his Euripides and Dionysos: An Interpretation of The Bacchae) of the danger of losing one’s individuality in the group, recognizing that participants “lose their sense of reality and their intellect and individuality as they succumb to a crowd mentality, a cult of emotion which tends to dehumanize.” Winnington-Ingram himself recognizes that his criticism of Dionysos’ penchant for turning his believers into a destructive mob may be related to having written during and after WWII, when the world was still struggling to recover from the devastation and horrors wrought by regimes that encouraged an abandonment of independent thinking for identification with the crowd, a danger evident in mobs everywhere and in any age. Two views of Pentheus As summarized in Mills, we tend to see Pentheus as the villain because of his: Consistent turn to violence, force, and imprisonment in response to opposition. Intolerance of new and therefore heterodox religious feeling. Lack of enough imagination to get outside his own preconceptions, even when confronted with evidence of the stranger’s divinity). Eagerness to believe the most lurid, sensationalist reports of the practices of the new cult. On the other hand, again per Mills, we have: His youth and inexperience as a ruler, which may contribute to his overreaction and overly militant reaction. The fact that his failure to recognize Dionysos as a god is partly engineered by Dionysos himself. His concern for the welfare of his city, which Athenians would approve and which we can sympathize with. Although we tend to applaud the liberation of women from being restricted to looms, kitchens, and cradles, the Greeks would see this liberation as a threat to the good functioning of society. Mills notes that this fear is somewhat justified—and Pentheus somewhat vindicated, not that it does him any good—by the tragic outcome of his mother’s assumption of the male role of being a great hunter. What both we and the ancients might see in the play In addition to the insights that nearly 2500 years of criticism have found in the play, we might notice the pairings, oppositions, and repetitions in contrast to each other, and in variations, much like Shakespeare’s rhetorical use of oppositions and pairings with variations in his Sonnets and in the plays, particularly in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In The Bacchae, Euripides presents and dramatically and poetically orders these devices of repetition, variation, contradiction, and contrast. As a result, the balancing of positive or negative, defensible or accusatory qualities of Dionysos and Pentheus in order to determine whether Euripides is morally pro- or anti-Dionysos, whether he is pro- or anti-Pentheus, or whether he is a believer in the gods or an atheist, pulls up well short of what the play accomplishes: the expansion of our ability to perceive life and the living of it in all its mutually contradictory aspects. This all-embracing perception may be expressed in the play’s instances of double vision. A vision that embraces contradictions begins with the Stranger. Dionysos tells us in the Prologue that he is taking the form of a man, and there is every reason for us to believe that the Stranger is that man that is Dionysos. But throughout the play, in his guise as the Stranger, Dionysos is so ambiguous about who he is, not just to Pentheus but also to us, we half forget the certainty he gave us in the Prologue: While we are sure that the Stranger is Dionysos, we also have an uncomfortable feeling that maybe we shouldn’t be so sure. In the Stranger’s first confrontation with Pentheus, the Stranger’s hints at his identity as Dionysos create, as well as good drama with comic overtones, the double vision of the Stranger, as both human and the god Dionysos. For example, “The god will free me himself, whenever I wish…. Even now he is close by and sees what I suffer.” Pentheus asks, “And where is he? For he is not visible to my eyes.” The Stranger answers, “Where I am.” The Stranger then directly faults Pentheus’ vision for being not double enough—not seeing both man and god in one—“But you being yourself impious do not see him.” When Pentheus sends the Stranger off to the stables for his imprisonment, the Stranger says, “In wronging us it is him [Dionysos] you take off to chains.” In the Third Episode, Dionysos as the Stranger plays havoc with his identity verbally, using three names for Dionysos and seeming to change within a single speech from frankly being Dionysos to speaking of Bakkhos (that is, Dionysos) in the third person, claiming only a mortal’s knowledge of Bakkhos. Still in the same speech, the Stranger tells how Pentheus tried to stab an image of light that Bromios (again, Dionysos) had created (implicitly, of himself), stabbing “at the shining <image> as if slaughtering me.” The effect is as if we were looking at Dionysos through a prism, in which he has become Stranger/Dionysos/Bakkhos/Bromios. Dionysos (as the Stranger) and Pentheus mirror each other with their use of rhetorical devices. This occurs in their contest, when they both use the same rhetorical device, in which one answers the other by repeating the structure of his opponent’s sentence, but with different words: At 489-90: Pentheus: “You must pay the penalty for your low sophistries.” Dionysos: “And you for your ignorance and being impious towards the god.” Then, at 504-5: Dionysos: “I, who have sense, tell you, who have no sense, not to bind me.” Pentheus: “And I, who have more authority than you, say to bind you.” In addition to their rhetorical aspect, these exchanges create the double vision in a contest of perspectives in which the two opponents, god and man, mirror each other. In the Fourth Episode, Dionysos, having dressed Pentheus as a woman, tells him that he looks “just like one of Kadmos’ daughters.” At that point, the double vision becomes explicit: Pentheus says that he sees “two suns, and a double Thebes…and you seem to be…a bull, and horns seem to be on your head. Were you a beast before? For you are certainly changed into a bull.” Dionysos tells him, “The god, being previously not well-disposed, is accompanying and at peace with us; now you see what you should see.” Dionysos is lying, of course, about how well disposed he is toward Pentheus, but a bull is in mythical fact the “real,” divine form of Dionysos, so that when Pentheus sees “two suns and a double Thebes,” he is seeing Dionysos as he really is. However, in this passage, the Greek word “tetaurosai” can mean either mean “you have been treating me with the savagery of a bull” or “you appear as a bull.” Thus even here, the language conveys its own double vision in its two meanings. The doubling moves into costuming and role-playing, as Pentheus asks how he looks. “Am I not standing like Ino stands or Agave, my mother?” And Dionysos completes the doubling of vision at this level: “In seeing you I seem to be seeing them in person.” When they are on their way out, Dionysos’ equivocating speech again toys with double meanings that foreshadow what is to come, but that the ignorant (Pentheus) can take in a completely innocent meaning. Euripides puts the literary device of foreshadowing to the work of doubling when, in the First Episode, at line 241, Pentheus brags that he will decapitate the Stranger. This foreshadows the climactic decapitation of Pentheus, but also links the decapitation imagery to both Pentheus and Dionysos, suggesting a double vision. The First Episode provides another piece of foreshadowing that will make us see Pentheus when Euripides’ play is talking about Dionysos, in imagery: At 436, the Servant who brings the Stranger/Dionysos bound before Pentheus describes the Stranger as “this beast,” because he is the object of the servants’ hunt. At the end of the play, Pentheus’ mother Agave will mistake him for a beast and lead the Bacchae in a hunt for him. The climactic confrontation is a tour of mass hallucinations in which one is seen as another and thus is two in the mind of the deranged. The final horrible recognition brings us back from hallucination to reality, and yet we’re left regarding with horror a human who was a beast. But don’t the fact of hallucination, the derangement of the Bacchae, Dionysos’ equivocation and lying all invalidate the double vision as a distortion of reality? We may see it that way, but the play undercuts every settled conclusion we arrive at, as in the problem of whether Euripides wants us to believe in the existence of Dionysos as an actual divine being, a god—apart from the problem of whether such a god is worthy of worship or respect, which he also leaves unsettled. Dionysos: god or symbol? Mills argues that we can’t too restrictively regard the play as presenting gods as actual beings. Alternatively, she suggests, we can see Dionysos as “[representing] a power that removes people from normality, for good or ill,” such as wine. Mills thinks that such a symbolic approach to the play may be more amenable to modern audiences than to ancient Greek audiences. Interestingly, however, the modern audience’s intense interest in character may actually work against a willingness to see a character primarily as a symbol. Mills also cautions, however, against holding too insistently to any one version or dimension of the Dionysos we see on stage. Seeing Dionysos as simply symbolizing “alcohol or drugs is obviously far too reductive.” She notes that a “purely symbolic approach, though not without validity, would be another perception of the god that would be as one-sided as Pentheus’ vision.” As one-sided a vision as seeing Dionysos strictly as a good would be. She suggests that “a more authentically Dionysiac reading of the play,” even if it involves accepting several conceptions of Dionysos that “are not mutually exclusive even if” they logically fight with each other “may be more rewarding. On this reading, Dionysos is a god, but also symbolizes that which takes us from the everyday to altered states. Some have gone even further and suggested that Dionysos represents a flexibility—intellectual and otherwise—which seeks a balance between the rational and the non-rational.” On the other hand, to find relevance for our lives in the play as we watch the story unfold today, our two most accessible paths are either to see Dionysos and Pentheus as symbols, or to see them as acting out interactions, dynamics, or responses to forces that we experience in our own lives. One need not advocate finding symbolism to admit that a great portion, maybe most, of the audience relates to symbolism as a powerful tool for finding the relevance of art to their lives. Let’s return to Dionysos as a god, for a moment. If he is a god, then the play makes us—and even more the original Greek audiences—ask whether Euripides was advocating belief or non-belief in the gods. Most notably and pathetically, at the end of the play is Kadmos’ objection to Dionysos: “It is not right for gods to resemble mortals in their anger.” (Dionysos’ answer, a very unsatisfactory one, is that the events that have just taken place were fated: “Long ago my father Zeus approved these things.”) Grube describes the error of making the play too much a means of expressing the poet/playwright’s beliefs, a means for communicating the poet’s supposedly intended message. Indeed, in the best art, finding a message is a dubious exercise at best. Indeed, one of the hallmarks of a smaller scope in lesser art is the existence of such intended messages. At the risk of committing that error, we can look at a question that has confounded critics, tending to form them into two opposing armies, possibly since Athenians gathered their robes and shuffled out of the Theatre of Dionysos after the tragedy’s premiere in 405 BCE. That question is, what is Euripides’ attitude toward the worship of gods in The Bacchae? Euripides has a reputation in his career to this point as being an atheist, a repudiator of the gods and of worship of them. In The Bacchae, do the irrefutable divinity of Dionysos and the folly of Pentheus turn back his own atheism for belief? Or does Kadmos’ objection suggest that as the Greeks understood them, the gods didn’t really merit belief? If we look at Dionysos and Pentheus not as symbols or literal gods and people but as simply as characters in a story who affect our feelings about them, then we see that however powerful Dionysos may be, we are finally repulsed by his bloodthirsty bent for revenge. At the same time, however reasonable Pentheus may be in fighting against the Bacchic cult, he is also unsympathetic in his methods. The result is a story with characters who defy attempts to resolve or eliminate the conflicts within them and who have therefore enabled millennia of critics to find multiple readings of The Bacchae and of Euripides, whom they have never successfully pinned down to a single position. Treatment of the characters as timeless figures in a story leaves us grasping for actualities to attach to them (actual god, actual human) or for a symbolism that would give them some kind of body. Thus Mills’ caution pertains not just to reading Dionysos strictly as god or as symbol, but also as character. The Bacchae leaves us with no easy answers, just questions. Surely the leading question is, how did the spectacle we just saw affect us in our knowledge of ourselves and the world? Sources for this article, and further reading There has been far more scholarship on Greek religion, theatre, tragedies, and, among the tragedies, The Bacchae, than is possible to even think about summarizing or reflecting here. The following are the sources that I used for this article, and further reading, which is really just a starting point for anyone interested in classic Greek tragedy and/or The Bacchae. Although I called out the sources separately, they belong with the other works cited in “Further reading.” Sources for this article Gods and Men: The Origins of Western Culture Henry Bamford Parkes The Greek Tragic Poets D.W. Lucas The Context of Ancient Drama Eric Csapo and William J. Slater Euripides and His Age Gilbert Murray Euripides: Bacchae Sophie Mills Dionysiac Poetics and Euripides’ Bacchae Expanded with a New Afterword by the Author Charles Segal Mills: “Fundamental to any consideration of the play.” Translations The Bacchae of Euripides Donald Sutherland Euripides: Bacchae Richard Seaford Further reading Greek history and culture, general The Greek Experience Bowra The Greeks and the Irrational E.R. Dodds A History of Greek Religion Martin Nilsson Before and After Socrates Francis Cornford Women in Athenian Law and Life R. Just Citizen Bacchae: Women’s Ritual Practice in Ancient Greece B. Goff Mills: “new and important reappraisal of women and cult in Ancient Greece”; “a fascinating account of women and Greek religion” Dionysos Dionysos, Myth and Cult W. Otto Mills: “Influenced by Nietzsche and Rohde. The ancestor of mainstream modern criticism of” The Bacchae. Greek tragedies, their origins, and the theatre The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy P. Easterling, ed. Includes Goldhill, “Modern Critical Approaches to Tragedy,” The Context of Ancient Drama E. Csapo, W.J. Slater, eds. Greek Tragedy Taplin Mills recommend: “Emphasizes the visual as well as the textual aspects of tragedy.” Greek Tragic Theatre Rehm Greek Theatre Performance: an Introduction D. Wiles Greek Theatre Practice J. Michael Walton Interpreting Greek Tragedy: Myth, Poetry, Text C. Segal Includes “Pentheus and Hippolytus on the Couch and on the Grid: Psychoanalytic and Structuralist Readings of Greek Tragedy,” per Mills “an excellent introduction to structuralist and psychological readings of tragedy. Tragedy and Athenian Religion C. Sourvinou-Inwood Mills: “Interesting if necessarily speculative account of the development of the Dionysia…. Discusses the religious and specifically Dionysian origins of Greek tragedy. Her conception of the gods in tragedy is very different from mine and well worth reading.” Also: includes “a detailed reconstruction” of how/when/in what setting, etc., the tragedies were staged. Inventing the Barbarian: Greek self-definition through tragedy Edith. Hall Mills: “a classic treatment of non-Greeks in tragedy” The Great Dionysia See above: “Context of Ancient Drama, The” and “Tragedy and Athenian Religion” Nothing to Do with Dionysos? eds. J. Winkler and F. Zeitlin Includes Goldhill, “The Great Dionysia and Civic Ideology.” Euripides The Drama of Euripides Grube, G. M. A. Euripides and Dionysos Winnington-Ingram Aspects Of Euripidean Tragedy L. H. G. Greenwood Catastrophe survived: Euripides' plays of mixed reversal Anne Pippin Burnett Essays on Euripidean drama Gilbert Norwood The Political Plays of Euripides Zuntz The Masks of Dionysos Thos. Carpenter Euripides R. Potter The Bacchae Criticism Dionysiac Poetics and Euripides’ Bacchae Expanded with a New Afterword by the Author Charles Segal Mills: “Fundamental to any consideration of the play.” Directions in Euripidean Criticism ed. P. Burian The City of Dionysos: A Study of Euripides’ Bacchae V. Lienieks Translations The Bacchae, edited with introduction and commentary by E.R. Dodds Mills: “fundamental reading” The Bacchae of Euripides: A New Version C.K. Williams Euripides’ Bacchae: The Play and Its Audience H. Oranje