L. Zhou and Z.J. Haas, ″Securing Ad Hoc Networks,″ IEEE

advertisement

Securing Ad Hoc Networks

Lidong Zhou and Zygmunt J. Haas

Cornell University

Abstract

Ad hoc networks are a new wireless networking paradigm far mobile hosts. Unlike

traditional mobile wireless networks, ad hoc networks do not rely on any fixed

infrastructure, Instead, hosts rely on each other to keep the network connected. Military tactical and other security-sensitive operations are still the main a plications

of a d hoc networks, although there is a trend to adopt ad hoc networe for commerciol uses due to their unique properties. One main challenge in the design of

these networks is their vulnerability to security attacks. In this article, we study the

threats an ad hoc network faces and the security goals to be achieved. W e identiFy the new challenges and opportunities posed by this new networking environment

and explore new approaches to secure its communication. In particular, we take

advantage of the inherent redundoncy in ad hoc networks - multiple routes

between nodes - to defend routing a ainst denial-of-service attacks. W e olso use

replication and new cryptogra hic sc\emes, such a s threshold crypto raphy, to

build a hi hly secure and high1 available key management service, wfich forms

the core o our security framework.

9

d hoc netwnrks arc a iicw paradigm of wireless

commuiiication for mohile hosts (which wc call

nodes). In a n ad hoc nctwork, thcre is no fixed

inlrastructurc such as basc stations o r mobilc

switching centers. Mobile iiodcs withiti cach othcr's radio r;ingc

cnmmunicatc directly via wirclcss links, while thosc that arc far

apart rcly on othcr nodcs to relay messages as rn~itcrs.Node

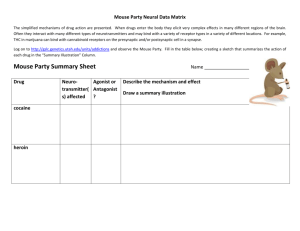

mohility in an ad lioc network causes frcquenl changcs of nctwork topology. Figurc I shows an examplc: initially, nodcs A

and D llavc ii direct link bctwccii thcm. Whcn D movcs out o l

A's radio range, thc link is broken. However, thc nctwork is

still cnnncctcd, hccausc A caii rcach D through C, E, and F.

Mililary tactical opcrations iirc still tlic main application of

ad hac networks today. b'nr cxmnplc, military units (c.g., soldicrs, tanks, or planes), cquippcd with wirclcss communicetioii dcvices, could form an ad hoc nctwork when thcy roam

in a battlcficld. Ad hoc networks can ;ilso lie uscd for emcr-

24

0890-8U441991$l0.00 0 1999 IEEE

gency, law enforcement, and rescuc missions. Sincc an ad hoc

network caii be deployed rapidly with relatively low cost, it

bccomes iui attractivc option fnr commcrcial uscs such as scnSOS nctworks or virtual classrooms.

Security Gods

Security is an important issuc for ad hoc nctworks, espccially

for sccurity-scnsitive applications. To sccure :in ad hoc network, we consider tlic fallowing attributes: availabilify, conpidentiaiulity, integrity, nutlienticalion, and nonrepudiation.

Availabilily ensurcs the survivability or nctwork services

despite dcnial-of-servicc attacks. A denial-of-scrvice attack

could bc launched ai any laycr of ;in ad boc nctwork. On the

physical and mcdia access control Iaycrs, an adversary could

cmploy jamming to interferc with communication on physical

channels. On the nctwork Iaycr, a n adversary could disrupt

the routing protocol and disconncct the nctwork. On the highcr layers, an adversary could bring down high-lcvcl serviccs.

Onc such targct is the kcy maiiagcnient scrvice, an cssential

scrvicc for any sccnrity framcwork.

Confidentiality cnsnres that certain information is nevcr disclosed to unaulhorizcd entitics. Network transmission of scnsitivc information, such as strategic 111 tactical military

information, rcqnires confidentiality. Leakage of such information to cncmics could have dcvastating consequcnces.

Routing information must iilso remain confidcntial in certain

cases bccause thc information might bc valuablc for eiiemics

t n idcntify and locate their targets in a battleficld.

Iritegri@ giiarantecs that a mcssage being transferrcd is never

corrnpted. A mcssage could be corrupted bccause of hcnign

[ERE Nclwotk

-

NovcmhedDeccmbcr 1999

1

failures, such as radio propagation impairment, or

hccausc of malicious attacks on the network.

Autlieriticution enables a node to ensure the

identity of thc peer node with which it is communicating. Without authentication, an advcrsary could

masquerade as a nodc, thus gaining unauthorized

acccss to resource and sensitive information and

intcrfering with the operation of olhcr nodcs.

Finally, nonrepudiution ensures that tlic origin of

a mcssagc cannot deny having sent the message.

Nonrcpudixtion is uscful for detcction and isolation of compromised nodes. When node A rcceivcs

an crroncous message [rum node B, nonrcpudiation allows A to accuse B using this message and lo

convince othcr nodcs that B is compromised,

Thcre arc othcr security goals (e.g., authorization) that arc of concern to certain applications,

but wc will not pursue tlncse issues in this article.

Challenaes

"

The salient features of ad hoc nctworks pose both challcnges

and opportunitics in achieving these security goals.

First, usc of wireless links rcndcrs an ad hoc network susceptihle to link attacks ranging from passive eavesdropping to

active impersonation, message rcplay, and mcssagc distortion.

Eevesdropping might givc an adversary access to secrct information, violating coniidcntiality. Active attacks might allow thc

adversary to delctc messages, to inject erroneous messages, to

modify mcssagcs, and to impersonate a nodc, thus violating

availability, integrity, authentication, and nonrepudiation.

Sccond, nodes roaming in a hostile cnvironment (e.g., a

battlcfield), with relatively poor physical protcction, have nonncgligihlc probability of bcing compromiscd. Thcrelorc, wc

should not only consider malicious attacks from outside a nctwork, but also take into ~ c c o u nthe

t attacks launchcd from

within the network by compromised nodes. Thercforc, to

achicve high survivability, ad hoc networks should have a distributed architecture with no cciitral entities. lntroducing any

central entity into our security solution could lead to signilicant vulncrahility; that is, if this centralized entity is compromised, the entire network is subvertcd.

Third, an ad hoc network is dynamic hecause of frequent

changes in both its topology and its membership (i.e., nodes

frequently join and leave the network). Trust relationships

among nodes also change, Sor cxample, when certain nodcs

arc detected as heiiig compromised. Unlike other wirelcss

mobile networks, soch as mohile IP

1, nodes in an ad hoc

network may dyn;imic;illy hccomc a

ited with administrative domains. Any security solution with a static configuration

would not suffice. It is desirable for our security mcchanisms

to adapt on the fly to these clnangcs.

I'ioally, an ad hoc network may consist of hundrcds o r even

thousands of nodcs. Sccririty mcchanisms should hc scalablc

to handle such a large network.

Scope and Roadrnap

Traditional sccurity mechanisms, such as auihciiticatioii protocols, digital signature, and encryption, still play important

roles in achicving confidentiality, integrity, authentication, and

nonrcpudiation of communication in ad hoc nctwnrks. However, these mechanisms are not sufficient by thcmsclvcs.

We lurther rely on the following two principles. First, we

take advantage of redundancies i n thc network topology (i.e.,

multiple routes between nodes) to achieve availahility. Thc

second principle is distrihufion ofrrrist. Although no single

node is trustworthy in an ad hoc network hecause of low physical security and availahility, wc can distribute trust to a n

-

IEEE Nclwork NovcmbcdDcccmbcr 1999

(b)

- _ ~

_ - _

_____

Figure 1 lbpologv rhnuges in ad hoc networks Nodes A, R, C, D,15, ond

l~conrtrtrilean ad hoc network The circle represents the radu range of

node A. The network rntrully has the topoloby in a) When node 1)movea

out of the rodio range ofA. the network topolopy changes to that m b)

aggregation of nodes. Assuming that any f t 1 nodes arc

unlikcly to all he compromised, consensus o l at least t t 1

iiodcs is trustworthy.

In this article, we will not addrcss denial-of-scrvicc attacks

toward the physical and data link layers. Ccrtain physical layer

comntcrmeasiires such as spread spectrum have hecn extensivcly sludicd [4-81. However, we do focus on how to deSend

against dcnial-of-servicc attacks toward routing protocols in

the following section.

All key-based cryptographic schemes (e.g., digital signature)

dcmand a key management service, which is rcsponsihlc for

keeping track oS bindings heiwccn keys and nodes, and assisting the estahlislnment of mutual trust and sccurc communication bctwccn nodcs. We will focus our discussion later on how

to cstahlish such a key managcrnent scrvicc that is appropriate

for ad hoc networks. We then prescnl rclated work and conchide in the last section.

Secure Rouiing

To achieve availability, routing protocols should he robust

against both dynamically changing topology and malicious

attacks. Routing protocols proposcd For ad hoc networks cope

well with thc dynamically changing topology [9-161. However,

nonc of thcni, to our knowledge, have accommodated mechanisms to defend against malicious attacks. Routing protocols

for ad hoc nctworks are still under active research. Thcre is

no single standard routing protocol. Thcreforc, we aim to capture the common sccurity threats and providc guidclincs to

secure routing protocols.

In most routing protocols, routers exchange information on

the topology of the network in ordcr to establish routes

between nodes. Such information could become a target lor

malicious advers;iries who intcnd to bring the network down.

There are two sources of threats to routing protocols. The

first comes from cxternal attackers. By injccting crroncous

routing information, replaying old routing information, or distorting routing infnrmation, an attacker conld successfully partition a network or introduce exccssivc trallic load into the

network hy cmsing retransmission and inellicicnt routing.

Tlnc second and more severe kind of threat comes from compromised nodes, which might advcrtisc incorrcct rooting information to (ither nodes. Detection of such incorrect information

is difficult: merely requiring routing information to he signed by

each node would not work, bccausc compromised nodes are

able to gccneratcvalid signatures using thcir private keys.

To defend against the first kind of threat, nodes can protect

routing information in the same way as thcy protect data traffic, that is, through thc use of cryptographic schemes such a s

digital signature. However, this dcfcnsc is incffective against

25

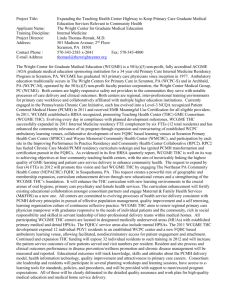

W Figure 2. The configuration of a key management service. The

key management service cori,si,stsofn servers. 7 % service,

~

a.?11

whole, has a publiclprivuiepair Klk Tiiepublic key K i,s known

to all nodes in the network, wliereos theprivate key k is divided

inro n shares SI, SA ,, .,sn, one share Joreach server. Each sewer

i also has rrpubliclprivate keypuir Kit$ and knows thepublic

1cey.s of all nodes

attacks from coniproiniscd servcrs. Worsc yel, a s wc liavc

argocd, we cannol neglect the possibility of nodes bcing comproiniscd in an ad hoc nctwork. Dctection of compromiscd

nodcs tlirough routing information is also difficult in an ad

hoc network hecausc of its dynamically changing topology:

w h e n a piccc of routing information is found invalid, the

information could he generated by a compromised node, or it

could have becomc iiivalid as a result of topology changes. It

is difficult to distinguish bctweeii thc two CHSCS.

On tlic. ollier hand, we can exploit certain propertics of ad

lioc networks lo achieve sccure routing. Note that routing

protocols for ad hoc nctworks niusl handle outdated routing

information to accornmodatc the dynamically changing

topology. False rooting information generatcd by comproiniscd nodcs could, to somc cxtent, bc considcred outdated

information. As long as therc are sufficiently many corrcct

nodes, the routing protocol should be able to find routcs

that go around tliese compromised nodes. S u c h clipability of

thc routing protocols iisually relies on the inhcreiit rcdundancies - multiplc, possibly disjoint, routes hctwecn nodcs

- i n ad hoc networks. If rouiing protocols can discovcr multiple routes (e.g., protocols i n ZRP [14], DSR [lOJ, TORA

11’21, and AODV [ l h ] all can achicvc this), nodes can switch

to an altornalive route wlicn the primary route appears to

havc failed.

Divemiq coding 1171 takes advantage of multiplc paths in an

efficicnt way witlioul mcssage retransmission. The basic idea

is to transmit redundant information through additional

routcs lor error detcction and correction. For cxamplc, if

there are 11 disjoint routcs betwccn two nodcs, we c m use n r channels to transmit data and use tlic otlicr r channcls to

lransmil redundant information. Evcn if ccrtain routcs are

compromised, thc reccivcr may still be able to validate mcssiigcs a n d recovcr them from errors using the redundant

informati~mfrom the additional r channels.

Key Management Service

Wc employ cryptographic sclicmes, such as digital signatures,

to protect both rooting information and data traffic. Usc of

such sclicmes usually requircs a key managcmcnl scmicc.

We adopt a public key infrastructurc hccause of its supcriority in distributing kcys, and achicving integrity and noiircpudiation. Efficicnl secrct key schemes are uscd to securc

further communication after nodcs autlicnticate cach othcr

and establish a sharcd secrct scssion kcy.

In a public key infrastructure, each node has a publiclprivate kcy pair. Public kcys can bc distributed to other nodcs,

while privale kcys should be kcpt confidcntial to individual

nodes. Therc is ii trustcd entity called a certification uuthority

26

(CA) [IS-201 [or key inanaeement. The CA has a publiclprivatc kcy pair, wilh its public key known to evcry node, and

signs certificates binding public keys to nodes.

Thc trustcd CA hiis to stay onlinc to rcflect thc currcnl

hindings, becausc the bindings ciiuld changc ovcr limc: a public key should bc rcvokcd if the owner niide is no loiigcr trustcd or is out ol thc network; a nodc may rcfresh its key pair

periodically to reducc the chance of a succcssful brute force

attack on its privatc kcy.

It is problematic to establish a key management service

using a single CA i n ad hoc networks. Thc CA, rcsponsiblc

lor the security of thc entirc nctwork, is a vulnerablc poini of

thc nctwork: if the CA is unavailablc, nodcs cannot get thc

current public kcys of other no& or cstablish secure communication with otlicrs. If thc CA is comprnmiscd and leaks its

privatc kcy lo an advcrsary, thc ;~dversarycan then sign any

crrniieous certificate using this private kcy to impcrsonate any

nodc o r to rcvoke any certificate.

A standard approach to improvc availability of a scrvice is

rcplication, but a naivc replication of thc CA makes the scrvice

more vulncrable: compromisc of m y singlc rcplica, which posscsscs the scrvice private key, aiuld lcad to collapse of tlie entirc systcm. To solve this problem wc distribute trust to a sct of nodes by

letting these nodes sliarc the kcy managcment responsibility.

The Sysiem Model

Our key matiagemcnt scrvicc is applicable to an asynchronous

ad hoc network; that is, a network with no hound on mcssage

delivery and proccssing times. Wc also assume that the undcrlying nctwork laycr providcs reliable links.’ Tlic scrvice, as a

whole, lias a publiclprivatc key pair. All nodes in thc systrm

know thc public key of the servicc and trust any certificates

signed using the corresponding privatc key. Nodes, as clients,

can submit query requcsts to gct othcr clients’ puhlic kcys or

submit ulidate rcqncsls to changc tlicir own public kcys.

Internally, our kcp management service, with an ( n , t t 1)

configuration ( n 2 31 + I), consists of n special nodes, which we

call server,s, prcscni within an ad hoc network. Each servcr also

has its own key pair and stores thc public keys of all the nodes

in tlic nchvork. In particular, each scrvcr knows thc public keys

of othcr scrvers. Thus, SCNCKS can cstablish securc links among

them. Wc assumc that thc adversary can compromise up t o t

scivcrs in any period of timc cif a certain duration.2

If a server is compromised, tlic adversary hiis access to all

the secrct information storcd on thc servcr. A comprnmiscd

servcr might he unavailablc o r exliibii Byzanline bchavior

(i.e., it can dcviate arbitrarily from its protocols). Wc also

iissumc that l l i e adversary lacks thc computational power to

break thc cryptographic schemcs wc employ.

Thc scrvice is correct if thc following two coliditions hold:

(Robustness) Thc scrvice is always able to process query

and updatc requests from clients. Every query always

rcturns thc lasi updated public kcy associated witli the

requested clicnl, assuming no coiicurrciit updates ou this

entry.

* (Cunficlentiality) The privalc kcy of thc servicc is never disclosed to an advcrsary. Thus, an adversary is nevcr able to

issoc certificates, signcd hy tlic servicc privatc kcy, Sor crroiicoiis bindings.

I Our-key management ,se,vi<m acriially woik,y ~ m d w

n niuck weaker.link

asmmplion, which i.r more uppropriatcfm ad hoc network.?. We leave

such detail,^ to U seprufr.urlicle currently inprqmation.

The drrrulion depends on how ojim and how jk.sl share rej>c.shi,z# (dis

cussed i x the nwit section) i.s done

IEEE Nclwurk

NavcmberlDcccmhcr 1999

_ _ _ ____

~

Threshold signature Klk

robust combining schcmcs are propnscd [21, 241. Thesc

schemes cxploit the inherent rcdundancics in tlic partial signatures (note that any t 1 correct partial signaturcs contain

all the information of the final sigtxiture) and use crror correction codes to mask incorrcct partial signatures. In 1231, a

robust threshold Digilal Sigiidturc Standard (DSS) scheme is

proposed. The process of computing a signature from partial

signatures is essentially an interpolation. The authors usc the

Berlekamp and Wclcli decoder s o that the interpolation still

yields a correct signature despite a m a l l portion (fewer than

onc fnurth) of partial signatures being missing or incorrect.

+

Server 1

m

Server 2

I

\I

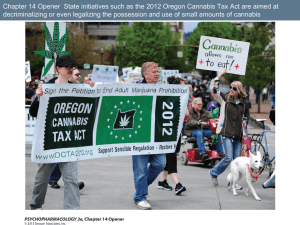

3.lhreshold signature. Given a sewice consirling of

three servers, let Klk he the puhliclprivute /<cypair of the service.

Using a (3, 2) threshold cryptography scheme, each seiver i gets

a shore q ofthe private key k. For a nmvage m, sewer i can generate a partial signature PS(m, sJ using its share si. Correct

sewers I and 3 hoth generate partial .sigiiature,sand forwnrd the

signnturer to a combirier c Even though sewer 2 failr to su6mit

a partial signature, cis able to generate the signature (m)k of in

signed by serverprivate key k

W Figure

Threshold Cryptography

Distribution of trnst in our key managemcnt service is accomplished using threshold cryptography [21, 221. An ( n , t t I)

threshold cryptography scheme allows n parties to share tlic

ability lo perform a cryptographic operation (e.g., creating a

digital signature) so that any t 1 parties can perform this

operation jointly, whereas it is infeasible for at most t parties

to do so, cvcn by collusion

In o u r casc, thc tt servcrs of the kcy management scrvice

share thc ability to sign certificates. For the service to tolcrate

t compromiscd servers, wc employ an ( n , f + I ) thrcshold

cryptography schemc and divide the private key k of the scrvice into n sharcs (SI,SZ, ,.., s,,), assigning onc share to each

sewcr. We call (si,s2, ..., s,? an (11, t 1) sharing of k. Figure

2 illustrates how the service IS configurcd.

For the service to sign a certificate, each scrver gcnerates a

partial signature for the certificate using its private key sharc

and submits the partial signature to ii

With t + 1

correct partial signatures, the combiner is ablc to compute the

signaturc for thc ccrtificatc. Ilowevcr, compromised servers

(there arc at most t of them) cannot gcnerate correctly signed

certificates by theniselvcs, because they can geuerale at most t

partial signatures. Figurc 3 slinws how scrvcrs gcncrnte a signature using a thrcshold signature scheme.

When applying thrcshold cryptography, we must defend

against cvmpromiscd servers. Far example, a compromiscd

servcr could gcncrate an incorrect partial signaturc. Use o l

this partial signature would yield an invalid signalurc. Forlunately, a combiner can verify thc vtilidily of a computcd signature using the scrvicc public key. In casc verification lails, the

combiner trics another set o l t t 1 partial signaturcs. This

process continues until the comhincr constructs thc correct

signature from t t I corrcct partial signatures. More efficient

+

+

"Auyseerver cnii hc a combim,: No exIra infu,malion about k is disclaveil

to a combiner. To make sure tlrot U compromi.sed conibher cannot p e veiit a signarsrrfmm being computed, we cuii use t

I setoera ns combin-

+

er.~to e i i ~ ~ ithat

l r at least one conihimr is cvmct and

+

SI,

+

+

4 Note that the tern

Qierntur

NuvemhcrlDcccrnher 1999

mobilc hcrr is diffwentfom drat in mobile noworlks.

+ here could be an addition opmtiun on n Jinitejeld such as

Z,, where (a

signatwe..

IEEE Network

able IO compute lhe

Proactive Security and Adaptability

Besidcs threshold signaturc, our key managcmcnt service also

cmploys share refreshing to tolerate rnobile adver.vnries4 and to

adapt its configuration to changes i n the network.

Mobile adversaries arc first proposed by Ostrovsky and

Yung to characterize adversaries that temporarily compriimise

x server and then movc on to the next victim (e.g., in form of

viruscs injected inio 21 nctwork). Under lhis adversary model,

an xlversaiy might bc ahlc to compsomisc all the scrvcrs over

B long period of time. Even if the compromised scrvcrs arc

detectcd and excludcd frvm thc scrvice, the advcrsary could

still gather morc than t sharcs uf the privatc key from conipromised servers over time. This would allow the adversary to

gencrate any valid cerlificatcs signed by thc private kcy.

Proactivc scliemcs [26-30] arc proposed as a countermcasure to mobilc adversaries. A proactive threshold cryptography scheme USCS share refrcshing, which cnables servers to

compute new sharcs from old ones in co1l;iboralion without

disclosing the scrvicc private key to any server. The ncw

s h a m constitute a new ( n , t + I) sharing of the scrvice privatc key. After refreshing, servers rcmovc the old shares and

use the new nncs to gcncrate partial signatures. Because the

new shares arc independent of thc old ones, thc adversary

cannot combine old sharcs with new ones Lo recover thc private key of the service. Thus, the adversary is challengcd lo

compromise t t 1 seivcrs between pcriodic refreshing.

Share refreshing relics on the following Iioniumorphic

propert If sl,si, .,.,.s!~) is an (n, t + I) sharin of k and (sl,

... .s$ is :n (n, t 1) sharing of kz, then (sI? t sf) .si t sz,

... t sf)' is an ( I ! , t t 1 ) sharing of k , + k 2 . 111~2is 0, wc

get a new (n. t t 1) sharing (if kc.

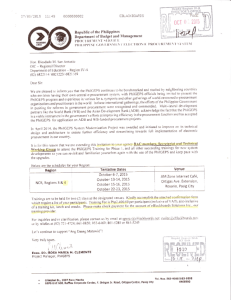

Given n scrvcrs, let (s,, 9 2 , ..., s.) be an (n,t t I) shariug

of the privatc key k cif the service, with scrvcr i having si.

Assuming ;ill servers arc correct, share refreshing procecds as

follows. First, cach server randomly gcncratcs ( s i l , sizr ...,si,,),

an (n, t t 1) sharing of 0. We call these newly gcncratcd sys

sirbskares. Then every suhsharc sij,is distribntcd to scrvcr j

through a securc link. When scivcrj gels thc suhsharcs slj, .sq.

..., s,,~,il can compute a ncw share from these subshares and

its old share (s'j = sj Z'/=,sij). Figurc 4 illustratcs a share

rcfrcshing proccss.

Share refreshing must toleratc missing suhsharcs and crroneous subshares from compromiscd servers. A compromised

server may not scnd a n y suhsharcs. Howcvcr, as long as corrcct servers agrcc on tlic sct of subshares to use, they can gencrate ncw shares using only subsharcs generated from t 1

servers. For seivcrs to detect incorrecl suhsharcs, wc use vcrifiable secrct sharing schcmcs (e.g., those i n [31, 321). A vcrifiable secret sharing scheme gcncrxtes extra public informalion

+ I>) mmrs (a + I>) niod p.

27

U Figure 4.Share repeshing. Given an (n, t t 1) sharing (sl. ...,

sJ of a private key k, with ,share q assigned to server i, to gener-

ate a new (n. t + 1)sharing (si, ..., si,) of k each server igenerates subshares sil,siz, ..., sin which constitute the ifh colninn in

the figure. Each subshare si, is then .sent securely to serverj.

which constiWhe,~seiver j gets all the subshnres sl,,sq, ,..,

tute the jth row, it can generate its news lare s!J!of?om these subshare.? and its old share si

for cach (su1i)share using ii onc-way function. ‘llle public

information can testify to thc correctness of the corrcsponding

(sub)shares without disclosing tlic (sub)shares.

Avarktion of share refreshing also allows the key management service to change its configuration from (n, t t 1) lo (n’, t’

+ 1).This way, the key managerncnt scrvice can adapt itsclf, on

the fly, to changes in the network if a compromised servcr is

detected, thc scrvice should exclude thc compromised server aud

refresh the exposcd sharc; if a server is no longcr available or a

new server is added, thc scrvicc should change its configuration

accordingly. For examplc, a key management servicc may start

with the (7,3) configuration. If, after some time, onc scrver is

detected to bc compromised and anothcr is no longer available,

the servicc could change its setting to thc (52) configuration. If

two new servers are addcd later, the service could changc its configuration back to (7,3) with thc ncw sct of servers.

This problem has bcen studied in [33].Thc esscncc of the

proposcd solution is again sharc rcfreshing. The only diffcrence is that now thc original set ol servcrs gcncrate and distribute subshares bascd on the new configuration of the

service: for a set o f t + 1 of t h e n old servcrs, cach server i

in this sct computes an (n’, t’ + 1) sharing (si,, si*, ..., sin,)of

its sharc s i and distributes subsharc so secretly to the j t h

server of thc n‘ new servers. Each ncw scrver can then compute the new sharc from these subshares. Thcsc ncw shares

will constitutc an (n’,t‘ ‘I)sharing of the same service private key.

Note that sharc rcfrcshing does not cbmge the service key

pair. Nodes in the network can still use the same scrvicc public kcy to verify signed certificatcs. This property makcs share

refreshiug transparent to all nodcs, and hence scalable.

+

Asynchron y

Existing threshold cryptography and proactivc thrcshold cvptography schemes assume a synchronous system (i.e., there is

a bound on mcssage delivery and messagc processing timcs).

This assumption is not necessarily valid in an ad hoc nctwork,

considering thc low reliability of wircless links and poor con-

28

nectivity among nodcs. I n [act, any synchrony assumption is a

vulnerability in the system: thc adversary can launch denial-ofservicc attacks to slow down a node or to disconnect a uodc

for a long enough period of timc to iiivalidatc thc synchrony

assumption. Conscqucntly, protocols based on the synchrony

assumption are inadcquate.

To reducc such vulnerability, our key managcmcnt service

works in an asynchronous setting. Dcsigning such protocols is

hard; some problems may even bc impossible to solve [34].

The main difficulty lies in the fact that, in an asynchronous

system, wc cannot distinguish a compromised scrvcr from a

correct but slow one.

One basic idea underlying our design is thc notion of weak

consistcucy: we do no1 requirc that the corrcct S C N ~ ~beS consistcnt after each opcratiou; inslead, wc require that enough

correct servcrs bc up to date. For cxample, in share rcfrcshiug, without any synchrony assumption, a server is no longer

able to distribute the siibsharcs to all correct scrvcrs using a

reliablc broadcast channcl. I-Iowcver, we only rcquire snbshares to bc distributed to a quorum of servers. This suffices,

as long as correct scrycrs in such a quorum can jointly provide

or compute all thc subshares that arc distributed. This way,

corrcct servers not having certain subsharc(s) could recover

thc subshare(s) from othcr correct servers.

Anotlicr important mcchanism is the use of multiplo signatures for corrcct servers to dctcct and reject erroncous messages scnt by comprorniscd scrvcrs. That is, wc rcquire that

certain messagcs be accoinpanicd with enough signatnrcs

from servers. If a message contains digital signaturcs from a

certain iiumbcr (say, t t 1) of servcrs testifying to its validity,

at least one correct server must havc provided one signature,

thus establishing the validity of the mcssage.

Wc have implemcntcd a prototype of such a key managemcnt scrvice. The preliminary results havc shown its feasibility. Due to thc lcngth restriction of this article, we arc unable

to provide a dctailcd description of this service. Full papers

dcscrihing the key management servicc and its underlying

proactivc sccret sharing protocol in an asynchronous system

are in prcparation.

Relafed

Work

Secure Routing

Secure routing in networks such as the Intcrnct has been

extensively studicd [9, 35-39], Many proposed approaclics are

also applicablc to secure routing in ad hoc nctworks. To deal

with external attacks, standard scbcmes such as digital signatures to protect inlormation authenticity and integrity have

bccn considered. For cxaniple, Sirios and Kcut [37] propose

the use of a keyed one-way hash function with a windowed

sequence numbcr for data integrity in point-to-point communication and the usc of digital signaturcs to protect messages

scnt to multiple destinations.

Perlman studies how to protcct routing information from

compromised routcrs in the context of Byzantine robustness

[35].The study analyzcs the theoretical fcasibility of maintaining network counectivity under such assumptions. Kumar recognizes thc problem of compromised routers as a hard problem,

but providcs no solution [36]. Other works [9,37,38] give only

partial soliitions. The basic idea undcrlying these solutions is to

detect inconsistcncy using redundant information and to isolate

compromised routers. For cxample, in [38], where methods to

secure distance-vector routing protocols are proposed, extra

information of a predecessor in a path to a destination is

added into each entry in the routing tablc. Using this piece of

information, a path-traversal techniquc (by following the predecessor link) can be used to verify the correctness of a path.

-

IBEE Network NovcmbcriDcccmbcr 1999

Such mechanisms usually come at a high cost and arc avoidcd

(e.g., in [9]) because routers on networks such as the Internet

are usually well protected and rarcly compromised.

ReplicatedSecure Services

The concept of distributing trust to a group of servers is investigated by Reitcr [40]. This is thc foundation of the Rampart

toolkit [41]. Reiter and others have successfully used the

toolkit in building a replicatcd key management service, Cl,

which also employs threshold cryptography [42]. Onc drawback of Rampart is that it may removc corrcct but slow

servcrs from the group. Such rcmoval rcnders the systcm at

least temporarily more vulnerablc. Membership changcs are

also expensive. For these reasous, Rampart is more suitable

for tightly coupled networks than for ad hoc networks.

Gong applies trust distribution to a key distribution center

(KDC), thc central cntity rcspoiisiblc for key managcmeut in

a secret key infrastructure [43]. In his solution, a group of

servers jointly act as a KDC, with cach scrver sharing a

unique secret key with each client.

Malkhi and Reiter present Phalanx, a data rcpository servicc

that tolerates Byzantine failures in an asynchronous system, in

[44]. The essence of Phalanx is a Byzantinc quorum systcm

[45]. In a Byzantinc quorum system, servers are grouped into

quora satisfying a certain intersectinn prnpcrty. Thc servicc

supports read and write opcrations, and guarantees that a read

operation always rcturns thc result of the last completed write

operation. Instcad of rcquiring cach corrcct servcr to perform

each operation, the service performs each operation on only a

quorum of scrvers. However, this weak consistclicy among the

servers suffices to achievc giiarantccd service because of the

intersection propcrty of Byzantine quorum systems.

Castro and Liskov [46] extend the replicated state-machine

approach [47] to achieve Byzantine fault tolerance. They use a

thrce-phasc protocol to mask away disruptive bchavior of

compromised servers. A small portion of servcrs may bc left

behind, hut can recnvcr by communicating with other scrvers.

Nonc of the systems provide mechanisms to defeat mobile

adversaries and achicve scalable adaptability. The latter two

solutions do not consider how a sccret (a privatc key) is

shared among thc replicas. Howevcr, they are uscful in building highly secure services in ad hoc nelworks. For cxamplc, we

could use Byzantine quorum systems to secure a location

databasc [48] for an ad hoc network

Security In Ad Hoc Networks

An authentication architecture for mobile ad hoc nctworks is

proposed in [49]. The proposed schcme details the formats of

messages, together with protocols that achieve authcntication.

The architecture can accommodate different authentication

schemes. Our key managemcnt service is a prerequisite for

such a security architccture.

Conclusion

In this article, we analyze the security thrcats an ad hoc nctwork faces and present the security objectives that need to he

achieved. On onc hand, the security-sensitive applications of

ad hoc nctworks requirc a high degree of sccurity; on the other

hand, ad hoc networks are inhcreiitly vulnerable to security

attacks. Therefore, sccurity mcchanisms are indispensable for

ad hoc networks. Thc idiosyncrasy of ad hoc networks poses

both challenges and opportunities for these mechanisms.

This article focuses on how to sccure routing and how to

establish a secure key management semicc in an ad hoc networking environment. These two issucs are cssenlial to achicving our

security goals. Bcsides the standard security mechanisms, we

IOEE Nehvork

Novcmher/DiDcccrnher 1999

take advantage of the redundancies in ad hoc network topology and usc diversity coding on multiplc routes to tolcrate both

benign aiid Byzantine failurcs. To build a highly availablc and

highly securc key managcmenl servicc, we proposc to use

threshold cryptogruphy to distrihutc trust among a set of

servers. Furthermore, our kcy management service employs

share rcfreshiug to achieve proactive sccurity and adapt tn

changcs in the nctwork in a scalable way. Finally, by relaxing

the consistency requirement on the servers, om- scrvice does

not rcly on synchrony assumptions. Such assumptions could

lcad to vulnerability. A prototypc of the key management service has been implemcnted, which shows its feasibility.

The article reprcscnts the first step of our research to analyze thc security threats, undcrstand thc security requiremcnts

for ad hoc networks, and idcntify existing techniques, as well

as propose new mechanisms to secure ad hoc networks. More

work needs to bc done to deploy thcsc security mechanisms in

an ad hoc network and to investigate the impact of tlicse security mcchanisms on network performance.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Robhert van Renessc, Fred B.

Schneider, and Yaron Minsky for tlieir invaluable contribiitions to this work. We are also grateful to Ulfar Erlingsson

and the anonymous reviewers for their comments aiid suggestions that hclped to improve the quality of the article.

References

[ I ] J. loonnidir, D. Duchamp, and G. Q. Moguire Jr., "IP~BaredProlacolr b r

Mobile Internetworking," ACM SIGCOMM Comp. Commun. Rev. {SIGCOMM '911, vol. 21, no. 4, Sept. 1991, pp. 23-45,

[21 F. Terooko, Y. Yakore, and M. Tokoro, "A Network Architecture Providing Host

Migmlion Tmnrparen~,''S I K W '91, vol. 21, m. 4, Sept. 1991, pp. 209-20.

131 C. E. Perkinr, "IP MO ility Support," RFC 2002. Oct. 1996.

141 M. K. Simon et al., Spread Spectrum Communications, vol. 1-11, Cornpuler

Science Piers, Rockville, MD, 1985.

[51A . Ephremider, J. E. Wierelthier, and D. J. Baker, "A Design Concept for

Reliable Mobile Radio Networks with Frequency Hopping Signaling," Prac.

IEEE, vol. 75, no, 1, Jan. 1987, pp. 56-73.

(61 N. Shochom ond J. Wertcott, "Future Directions in Packet Radio Architecture

ond Protoocolr," Proc. IEEE, vol. 75, no. 1, Jon. 1987, pp. 83-99.

[7] A. A. Hasron, W. E. Stark, and J. E. Herrhey, "FrequencyHopped Spread

Spectrum in the Prerence of o Flower Portial~BondJammer," IEEE Trans.

Commun., vol. 41. no. 7, July 1993, pp. 1125-31

I81 M. B. Purrley and H. B. R u n d "Routing in Frequency-Hop Pocket Radio Networks with Partial-Band Jomming," IEEE Trans. Commun., vol. 41, no. 7,

July 1993, pp. I I 1 7-24.

191 S. Murphy ond J. J. Garcia~Luna-Acever,"An EAicient Routing Algorithm for

Mobile Wirelerr Networks," MONET, Oct. 1996, vol. 1, no. 2, p 183-97

(101 D. 8. Johnson and D. A. Maltr, "Dynamic Source Rouling in AdiHoc Wireless Networks," Mobile Comp., 1996.

[ I I ] J. Sharony, "A Mobile Radio Network Architecture with Dynamicolly

Changing Topology using Virtuol Subnetr," Prac. ICC/SUPERCOMM '96,

Dollar, TX, June 1996, pp. 807-12.

(121 V. D. Park and M . S. Corron, "A Highly Adoptoble Distributed Routing

Algorithm for Mobile Wirelerr Nelworkr," IEEE INFOCOM '97, Kobe,

Japan, 1997.

[13] C:K. Toh, "Associativity-Bared Routing for Ad Hoc Mobile Nefworkz,"

Wireless Pers. Commuo. J., Speciol 1sue on Mobile Networking and Computing Systems, "01. 4, no. 2, Mor. 1997, pp. 103-39.

1141 Z. J. Haos and M. Perlmon, "The Performonce of Query Control Schemer

for Zone Routing Protocol," SIGCOMM '98, June 1998.

[I51 P. Jacquet, P. Muhlethaler ond A. Qayyum, "Optimized Link State Routing

Protocol," IETF MANET, Internet draft, Nov. 1998.

(161 C. E. Perkinr ond E. M Royer, "Ad Hoc On-Demand Dirtonce Vector Routing," IEEE WMCSA '99, New Orleans, LA, Feb. 1999.

"Diversity Coding for Transparent Self-Healing and

[17l E. Ayanoglu et d ,

Fault-TolerontCommunication Networks," IEEE Trans. Commun., YOI.41, no.

11, Nov. 1993, pp. 1677-86.

11SI M. Gosrer et al., "The Digital Dirtributed Systems Security Architecture,"

Proc. 12th Nat'l. Comp. Securiw Cod, NIST, 1989, pp. 305-19.

[I91 J. J. Tordo ond K. Algappon, "SPX Global Aulhentication Urin Public Key

Certificates, Proc. IEEE Symp. Security and Privacy, Oaklon!, CA, May

1991, pp. 232-44.

(201 C. Kaufmon, " DASS: Distributed Authentication Security Service," RFC

1507, Sept. 1993.

29

1211 Y. Desmedt and Y. Frankel, "Threshold Cryptoryrtemr," Advoncer in Crypioloav - Cwolo '89 llecture Nofer in Comoulei Science 4351. G. Brassard,

Ed.,"~pringe;~Verlag, Aug. 1990, pp. 307-i 5.

[ 2 2 ] Y. Dermedt, "Threshold Cryptography," Euro. Troons. Telecommvn., "01. 5 ,

no. 4, July-Aug. 1994, p 449-57.

Threshold DSS Signatures," Advancer in Cryp[ 2 3 ] R. Gennaro el d,"Ro!u;t

toaroohv Pmc. Eurocrvpt '96 ltecture Noter in Computer Science 1070J,

S$n$lerlag,

May 1996. pp. 354-71

(241 R. Gennaro et al., "Robust and Efficient Sharing of RSA functions,"

A i o l v..

o.

n.~.in~ Crvofolonv

~ ,,~ ~ - ,

Crvob '94 ILecIum

Notes in Comoulei Science

,

IIOP), Springer~Verlag,Aug. 1996, pp. 157-72.

1251 R. Ortroviky and M. Yunq, "How to Withstand Mobile Virus Attacks," Proc.

-

~

~

~

~

,/

~

~~~

~

"~

~~~

(271 A. Herzbe'rg ;I al., "Proactive Secret Sharini or: H b to Cope with Perpetual

Leokage," Advancer in Crypdo y

Cryplo '95 1Lechm Noler in Computer

Science 9631, D. Coppersmith, E l , G g . 1995, SpringerNerlag, pp. 4 5 7 4 9 .

[28] A. Herzber el al. "Praoctive Public-Keyand Signature Schemer," Proc. 41h

Annual Coo? Corn;.

Commun. Security. 1997, pp. 100-IO.

[ 2 9 ] Y. Frankel dol., "Proactive RSA," Advances in Cryplology - Cryplo ' 9 7

/kclure Noler in Campuler Science 1294J, Springer~Verlag,U.S.A., Aug.

..

~. ._

(401 M. K. Reiter, "Distributing Trust with the Rampart toolkit," Carnmun. ACM,

vol. 39, no. 4, 1996. pp. 71-74.

[41] M. K. Reiter, "The Rampart Toolkit for building high-integrity Services," Theory and Proclice in Distributed Systems (lecture Notes in Compuer Science

9381. 1995.

99-1 IO.

1421 M.'K. R&kl al., "The R Key Manoaement Service,'' J. Como. Secuiihl,

.~

,.

vol. 4, no. 4, 1996, pp. 267-97.

(431 1. Gong, "Increaring Availobilily and Security of on Authentication Service,"

IEEE JSAC, vol. 1 I , no. 5 , June 1993, pp. 657-62.

[44] D. Malkhi and M. Reiter, "Secure ond rcolable replication in Phnlann,"

Pmc. 17th IEEE Symp. Reliable Dirt Sys., Oct. 1998, pp. 51-58.

[45] D. Molkhi and M. Reiter, "Byzantine Quorum Syrtems," J, Dirt Comp., vol.

Il,no. 4, 1998.

[ 4 6 ] M . Cortro and B. Liskov, "Proctical Byzantine Fault Tolerance," Proc. 3 r d

Symp. Op. Sys. Design and Implementotion, New Orleans, LA, Feb. 1999.

[ 4 7 ] F. B. Schneider, "Implementing Fault-Tolerant Services Using the State

Machine Approach: A Tutoriol," ACM Comp. Soweyr. vol. 22, no. 4, Dec.

1990, pp. 299-319.

(481 Z. J. Haas ond B. liong, "Ad Hoc Mobility Manogement using Quorum

Systems," IEEE/ACM Tronr. Net,, 1999.

[49] S. Jacobs and M. S. Corion, "WNET Authentication Architecture." Internet

draft (drah~iacobr-imep-outh-orch-01

.txtl, Feb. 1999.

1997

nn A A L Z d

,, , Pr

[ 3 0 ] Y. Fmnkel et ol.,"Optimal Reriliencc Proactive Puhlic~KeyClyptoryrtemr,"

Pmc, 381h 5ymp. Foundotioanr of Comp. Sei., 1997.

[31] P. Feldmon, "A Piacticol Scheme for Noninteractive Veriiiable Secret Shar~

ing," Proc. 28th IEEE Symp. Foundations of Comp. Sci., 1987, pp. 427-37.

(321 T. P. Pederren, "Noninteractive and Informotion~TheoreticSecure Verifioble

Secret Sharing," Cryplo '91 lteclure Noler in Computer Science 576J,

Springer~Verlog,Aug. 1992, pp. 129-40

[ 3 3 ] Y. Dermedt and S. Joiodia, "Redistributing Secret Shares to New Accerr

Structurer ond 11%Applications," Tech. rep. ISSEtTR-97-01, George Mason

Univ., July 1997.

1341 M. J. Fisher, N. A. lynch, ond M. S. Pekrson, "lmpaiibilityof Dirhibuted Consensus wih One Faulty Pmersor," J. ACM, vol. 32, no. 2, Apr. 1985, pp. 374-82.

[ 3 5 ] R. Perlman, "Network layer Protocols with 8yrontine Roburtnerr," Ph.D.

thesir, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Morsachmens In;titute of Technology, 1988.

( 3 6 ) 8. Kumor, Integration of secwily in network routing protocoli," SIGSAC

Review, vol. I I , no. 2, 1993, pp. 18-25.

[ 3 7 ] K. E. Siroir and S. T. Kent, "Securing the Nimrod Routing Architecture,"

Prac. Symposium on Nehvork ond Dislributed System Securiw, Los Alomitoi,

CA, Feb. 1997, The Internet Society, IEEE Computer Society Press, pp.

74-84.

1381 B. R. Smith, S. Murph ond J. J Garcia Luna~Acever,"Securing DistanceVector Routing Protoco~," Proc. Symp. Nehvork m i d Dirt Sys. Security. Los

Alomibr, CA, Feb. 1997, pp. 85-92,

[ 3 9 ] R. Haurer, T. Przygienda, and G. Trudik, "Lowering Security Overhead in

Link State Routing," Comp. Networks, Apr. 1999, vol. 31, no. 8, pp. 885-94.

30

Biographies

LIDONG ZHOU (ldrhou@cr.cornell.ed"] is a Ph.D. condidate in the Deportment of

Computer Science, Cornell Univerrily. He received hir 6.5. in 1993 and his M.S.

in 1998, both in corn uter xience. His reseclrch interests include distributed ryrtemr, security, fault t o ~ r m c e ond

,

wireless networks.

ment. Therk he pursued research on wireless communications, mobility ma&

ment, fast protocols, optical networks, and optical switching. From September

1994 to July 1995, he worked for the AT&T Wireless Center of Excellence,

where he investigated various clrpectr of wirelei3 and mobile neborking, concentrating on TCP/IP networks. In August 1995 he ioined the faculty of the

School of Electrical Engineering at Cornell Univerri 0 5 o w x i o l e proferror. He

is on outhor of numerous technical papers and h o l x 12 patents in the fields of

high-speed networking, wireless networks, and optical switching. He has or a

nized several Warkiho i , delivered tutorials ot m i o r IEEE and ACM con9.r:

ences, and serves CIS &or of ~ e v e r o liournclli. He bo, been (I guest editor of

three IEEE JSAC i i s ~ e s(Gigobit Networks, Mobile Computing Networks, and

Ad-Hoc Networks). He is CI votin member of ACM and o vice chair of the IEEE

Technical Committee on PerronagCommunicationr. His interests include mobile

ond wireleis communication and networks, personal communication sewice, and

high-$peed communicotion and protocols.

IEEE Nclwork * Novcmhcrll~cccmbcr1994