Building a Workplace Wellness Program

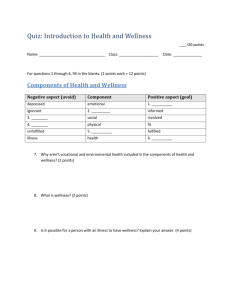

advertisement

Chapter One Building a Workplace Wellness Program What is wellness? Wellness is more than just the absence of illness. Over the years, the term evolved and has been re-defined many times. Now, definitions of wellness vary widely. We choose to use the following: Wellness is an intentional choice of lifestyle characterized by personal responsibility, balance, and maximum personal enhancement of mind, body and spirit. In the not-so-distant past, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and diarrhea were the major threats to our lives and health. Public health measures and the discovery of antibiotics reduced both the prevalence – and the seriousness – of these diseases. Today's major killers (heart disease, cancer and stroke – along with accidents for younger folks), have proved resistant to these traditional solutions. In fact, there are no simple cause and effect relationships between these diseases and bacterial, viral, and/or environmental conditions. The chart to the right indicates, lifestyle – the simple, everyday choices, made about how we eat, sleep, relax, exercise, drive, smoke, etc. – is the largest single contributor to present day illnesses and untimely deaths. Causes of illness and untimely deaths Lifestyle 51% Heredity & Other Biological Causes 20% Environment 19% What is health risk? The wellness approach to health is, in fact, based on the “health risk” approach to disease. The concept of health risk comes from the scientific observation that most of our major illnesses are associated with factors that predispose an individual to developing a particular disease or dying from a particular cause. While some health risk factors are outside of an individual’s control (like age, gender, ethnicity, family history, and certain other environmental factors) many, in fact most, are the result of individual choice (like tobacco use, physical activity, food choices, and other preventative measures like regular health screenings). Inadequate Health Care 10% AWC’s 2004 claims analysis has identified exercise, weight, and stress as the top 3 risk factors for the AWC population at-large for each of the three years 2001 – 2003, (all highly modifiable risk factors). To position wellness programs to have the greatest impact, it is important to understand the risks of the employee population. The aim is to increase the percentage of low risk employees to drive health care spending down as health risks drive health costs. May 2010 Chapter 1 Workplace Workplace Wellness Planner 1 In addition, wellness programs help to prevent the migration of low risk employees from becoming high risk. The chart below depicts how risk factors translate to health care costs by comparing the average spending for an individual at high risk for each risk factor. Health care costs increase for individuals at high risk 3000 $3000 Annual health care spending $2500 2500 $2535 2001 – 2003 $2000 2000 $2085 $1747 $1500 1500 $1263 $1000 1000 $1256 $1116 $837 500 $500 0$0 $568 Depression Blood Pressure Stress Diabetes Exercise Cholesterol Tobacco Weight $496 Nutrition Source: AWC Claims Analysis, 2004, Summex Health Management An Overall Wellness Score is calculated from risk factors and health behaviors for each individual who completes the health risk assessment questionnaire. A person with a score of 80 or below is considered to be at elevated risk for developing chronic disease that can greatly affect health care spending and quality of life. The Overall Wellness Score is based strictly on modifiable lifestyle habits. As the graph below indicates, 55% of participants have a wellness score placing them at elevated risk for one or more risk factors. Overall wellness score shows elevated risk for 55% of participants 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 33% 30% 21% 20% 10% 0% 14% 11% Under 75 75 – 79 80 – 84 85 – 89 Overall Wellness Score 2 Association of Washington Cities 20% 90 – 100 Risk factors for the top three causes of death Controllable risk factors: Non-controllable risk factors: Cardiovascular • Cigarette smoke • High blood pressure Disease • High blood cholesterol levels • Physical inactivity • Other contributing risk factors: diabetes, obesfty. stress • • • • Heredity – family history of heart disease Ethnicity Gender Age Selected Cancers Lung Cancer Controllable risk factors: • Smoking • Exposure to: asbestos, arsenic, certain organic chemicals, radiation, radon, side stream cigarette smoke Controllable risk factors: Non-controllable risk factors: Colon and Rectum Controllable risk factors: • Inflammatory bowel disease Cancers • High-fat and/or low-fiber diet Non-controllable risk factors: Controllable risk factors: Non-controllable risk factors: Controllable risk factors: Non-controllable risk factors: Breast Cancer • Never had children or late age at first birth • Higher education and socioeconomic status • Diet – especially high fat intake Skin Cancer • • • • • Heredity – family history of cancer or polyps of the colon or rectum • Excessive exposure to ultraviolet radiation • Occupational exposure to coal tar. pitch, creosote, arsenic compounds, or radium Prostate Cancer • High dietary fat intake Uterus and Cervix Cancers Controllable risk factors: Accidents Controllable risk factors: • • • • Over age 40, increases with age Heredity – family history Early age at menarche Late age at menopause • Fair complexion • Incidence increases with age – over 80% of all prostate cancers are diagnosed in men over 65 • More common in northwestern Europe and North America • African Americans have the highest incidence rate in the world Early age at first intercourse Multiple sex partners Cigarette smoking Certain sexually transmitted diseases • Lack of or improper use of seat belts or child restraints • Drinking while driving • Speed over 50 mph • Cigarette smoking • Chronic medical condition • Miles driven Non-controllable risk factors: • Age – experience Chapter 1 Workplace Workplace Wellness Planner 3 “America can only be as strong and healthy as its people.” Ronald Reagan Lifestyle does make a difference Studies show certain lifestyle habits turn up over and over again as risk factors (major or minor) for a number of serious diseases and medical conditions. Research also shows evidence that lifestyle can be changed, and that the changes reduce risks of premature death and disability. Major controllable risk factors and how they can be controlled have been identified as follows: Smoking Smoking is the single most preventable cause of death in Americans and 17.1% of adults in Washington smoke. (CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2006)* Smoking harms nearly every organ in the body, causing many diseases and reduced quality of life and life expectancy. (CDC, 2004) Not smoking and staying away from people who are smoking are the easiest way to eliminate health risks associated with this habit. High blood pressure Uncontrolled high blood pressure (hypertension) is a major risk factor for heart attack and stroke. Because there are no symptoms, only blood pressure measurement can detect hypertension. Although there is no known cure, once detected, high blood pressure can be controlled through diet, exercise, and, if needed, medication. High blood cholesterol An elevated blood cholesterol level increases risk of heart disease: the higher the blood cholesterol level, the greater the risk. A simple blood test can identify high blood cholesterol levels. Cholesterol levels can be controlled through diet, exercise, and, if needed, medication. Physical inactivity Lack of exercise and physical fitness is associated with obesity, heart disease, stress, depression, digestive disorders, osteoporosis, and a number of other health conditions. Studies show that although regular, moderate-intensity exercise is most beneficial to one’s health, even intermittent activity provides substantial health benefits. Out of all of AWC’s health risk assessment participants in 2007, 76.4% reported physical activity less than 4 times per week, with 13.6% reporting no exercise at all. 4 Association of Washington Cities Stress High level, prolonged stress is closely linked with leading causes of death and illness, including heart attack, stroke, cancer, diabetes, back pain, accidental injuries, alcoholism, obesity, and depression. In addition, chronic unrelieved stress, or the inability to manage stress effectively, aggravates nearly every health condition. According to a study by the Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO), stress and depression were the two risk factors associated with the greatest medical costs. Stress can not be eliminated completely from one’s life, but a lot can be done to prevent, manage, and control stress through exercise, good nutrition habits, relaxation, adequate sleep, and time management. Alcohol/substance abuse Alcoholism is the leading cause of cirrhosis of the liver and a major risk factor for motor vehicle injuries, depression, and suicide. Any drug that is misused will cause health risks of some sort. Eliminating abuse will eliminate health risks involved with using them. Failure to wear seat belts For individuals who drive or ride in a motor vehicle, the failure to “buckle up” greatly increases the risk of dying or suffering major injury from a motor vehicle accident. The simple task of putting on a seat belt and properly using child safety restraints can greatly reduce this risk. More than 90% of adults in Washington report wearing their seat belts most of the time. (Source: CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2006) Obesity Recent estimates indicate that 60.7% of adults in Washington State are overweight (36.5%) or obese (24.2%). (Source: CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2006) * In 2007, 64% of AWC’s health risk assessment participants were overweight or obese. Also, there has been an increase in body fat levels in children and youth over the past 20 years. After infancy and early childhood, the earlier the onset of obesity, the greater the likelihood of remaining obese. Obesity is associated with heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, back problems, arthritis and cancer. Maintaining appropriate weight through proper nutrition and exercise will reduce or eliminate the risk. Chapter 1 Workplace Workplace Wellness Planner 5 Statistically, if there are 100 people in your city or department . . . These figures have been calculated using AWC’s 2007 health risk assessment aggregate 4 have diagnosed diabetes 8 have depression 11 have high blood pressure 11 have anxiety report. 12 use tobacco 20 engage in high risk alcohol behaviors 23 have allergies 26 have moderate or severe symptoms of depression 28 have elevated cholesterol levels 30 are at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease 44 are considered prediabetic 57 are at risk for stress related disorders 64 are overweight or obese (BMI greater than 25) 76 are inactive = 5 people 6 Association of Washington Cities 93 do not meet recommended nutritional guidelines Building the case for wellness Total disability lost-time The cost of poor health In 2005, the AWC State of the Cities Report cited health care costs as one of the top issues impacting city budgets. Concern continues today as health care costs for Washington cities rose by 168% from 1997 – 2007. Even though health care trends have relaxed in recent years, the reality is that projected healthcare trends of 9 – 12% annually for the next several years is still 4 – 5 times the rate of general inflation (2.4% as of July 2007). costs exceeded medical costs by 58% Other direct costs to the employer associated with unhealthy employees include salaries to the absent employees – as well as added stress to coworkers and the cost of temporary replacement and administrative costs during their absence. The nation experienced a 25% increase in worker absenteeism in the 1990’s, a trend that is expected to continue, according to Total Health Advocacy Partners (2002), providers of employee health management programs for large employers. Another disturbing trend for employers is disability lost-time, which exceeded medical care costs in 2000. Base on data accumulated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Health Interview Survey, the Work Loss Data Institute completed a benchmarking evaluation of disability costs to U.S. employers. The study revealed that for all conditions combined, total disability lost-time costs exceeded medical costs by 58%. More difficult to measure are the indirect costs resulting from reduced productivity, diminished work quality, accuracy and safety, or presenteeism. Workers are at work by not fully engaged in their jobs due to a host of reasons such as being sick, fatigued, in pain, stressed or distracted by personal issues. Presenteeism is viewed as the opposite of absenteeism; employees being at work when they should be at home. Using a Worker Productivity Index to measure the indirect costs to employers, one research group was able to demonstrate statistically that the more health risks employees have, the lower their productivity (Burton, et al., 1999). In a comparison of low-risk coworkers at ten companies, high-risk employees cost more in medical claims, disability and workers’ compensation. They have a higher ratio of absenteeism and lower rate of productivity (UM/ HMRC, 2000). In AWC’s 2004 analysis of HealthCheck Plus participants, absenteeism rates decreased as health risk decreased. Chapter 1 Workplace Workplace Wellness Planner 7 Examples of the cost of poor health in workers: • The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported in 2002 that a smoking employee will cost employers on average $1,760 in lost productivity and $1,623 in excess medical costs per year. • The absenteeism rate for smoking employees is on average 50% more than for nonsmoking coworkers. • Estimates indicate that stress costs approximately $200 billion annually in decreased productivity, higher health care costs and higher absenteeism (Brown, 1998) • Heart disease accounted for 61% of all health care spending in 2001, an estimated $498 billion (CEC, 2002) • The indirect cost of lost productivity related to heart disease is projected to exceed $129 billion in 2002 when tabulated (American Heart Association). • The average annual per capita increase in medical expenditures and absenteeism associated with obesity ranges between $460 and $2,500 per obese employee, with costs increasing as body mass index increases. (American Journal of Health Promotion 2005) • Back injuries cost business $10 – $14 billion in workers’ compensation expenses and approximately 100 million work days each year, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2002). • Worksite injuries due to alcohol and drug abuse are associated with 40% of industrial fatalities (HR Focus, 1997). 8 Association of Washington Cities Workplace wellness makes an impact Employers are being forced to get involved in medical cost management. Cities in Washington encourage more healthy behavior by employees and many are considering options for incentives that encourage employees to make cost effective health care choices. The cost savings of workplace health promotion have been well documented in many studies. The overwhelming result: Changes in cost follow changes in risk. Medical costs decrease with increasing wellness score $2817 Annual medical costs $2700 $2508 $2369 $2200 $2087 $1800 $1643 $1700 $1415 $1200 Research conducted at General Motors by the University of Michigan has demonstrated the inverse relationship between a health risk assessment’s “wellness score” and annual medical expenditures. As the “wellness score” increase, the health care costs decreased. Source:Yen L, McDonaldT, Hirschland D, Edington, DW. Association between wellness score from a health risk appraisal and prospective medical claim costs. J Occup Environ Med. 2003; 45(10):1049-1057 65 70 75 80 85 Wellness score 90 95 A review of 73 published studies of worksite health promotion programs documents an average $3.50 – $1 saving-to-cost ratio in reduced absenteeism and health care costs. (Aldana, American Journal of Health Promotion, 2001) A meta-review of 42 published studies of worksite health promotion programs (Chapman,The Art of Health Promotion, 2003): • Average 28% reduction in sick leave absenteeism • Average 26% reduction in health costs • Average 30% reduction in workers’ compensation and disability management claims costs • Average $5.93-to-$1 savings-to-cost ratio Chapter 1 Workplace Workplace Wellness Planner 9 Savings per dollar invested in worksite health promotion programs Each $1 invested bought the following returns: From AWC’s 6-year returnon-investment analysis on the HealthCheck Plus program $4.50 was saved in excess health costs and reduced absenteeism A comprehensive health management program at Citibank $4.56-$4.73 to $1 in savings-to-cost ratio in reduced total health care costs From a review of 13 studies of worksite health enhancement programs $3.48 to $1 (average) in reduced health care costs A blood pressure control program at General Motors $3.10 to $1 in savings-to-cost ratio in reduced absenteeism (year 2) $5.82 to $1 (average) in lower absenteeism costs A medical self-care (demand management) program offered at Union Pacific Railroad $2.78 to $1 in savings-to-cost ratio in reduced outpatient costs (non-chronic conditions) $3.90 to $1 in savings-to-cost ratio in reduced absenteeism (year 3) A comprehensive mass communication program with field coordinators at The Travelers $4.50 to $1 saving-to-cost ratio in health care savings, decreased absenteeism, and increased productivity Disease management interventions $1.25 to $2.94 in savings-to-cost ratio in reduced medical care costs Sources: AWC 2004 Claims Analysis; Partnership for Prevention, Leading By Example, Executive Summary, www.prevent.org. 10 Association of Washington Cities Nationally, the move towards worksite health is being recognized as imperative; here in Washington State, cities are a major part of that movement. Since the mid-80’s, each year, more cities initiate worksite wellness programs. In 2006, 88% of AWC Employee Benefit Trust member cities participate at some level in employee wellness programs. From the 2002 study by Hewitt Associates (Health and Productivity Programs Continue to Grow in Popularity as Health Care Costs Rise, 7/02), here are the types of activities that a growing number of employers are offering their employees: • 72% provide education or training through seminars and counseling for lifestyle habits. • 42% offer financial incentives for program participation: or disincentives (e.g., higher premiums for smokers, or a lower payout for not using a seatbelt while in an accident). • 28% administer health risk appraisals to analyze individual health and promote early detection of preventable conditions (online applications make this process relatively easy and affordable). “The City of Bainbridge Island Wellness Program offers a point-based incentive system for employees that exercise regularly or quit smoking.” Marja J. Preston, AICP, Planner and Wellness Coordinator, City of Bainbridge Island. • 75% use health screenings primarily to detect high blood pressure, cholesterol, breast cancer and other conditions through health plans, fairs or mobile units. • 79% offer special programs, such as flu vaccinations, education in prenatal care and well-baby/child care, and disease and medical management (e.g., diabetes, asthma, arthritis). • 81% sponsor additional activities designed to heighten awareness of health behaviors. These activities include a smoke-free workplace (57%), onsite fitness facility (35%), company sports teams (30%) and health club discounts (23%). Chapter 1 Workplace Workplace Wellness Planner 11 Wellness benefits everyone High level city wellness program equals lower costs $4000 Wellness programs can present many benefits for employees, employers and their community. $3785 $3500 $3349 $3374 $3142 $3000 $2522 $2311 2001 l 2002 • Increased knowledge about the relationship between lifestyle and health • Increased opportunity to take control of their health and medical treatment $2500 $2000 Benefits for employees: 2003 High level program u Low-moderate Cities with a high level of wellness programming show health costs markedly below cities with low-tomoderate wellness programming efforts; the average savings over the study period was nearly $300 per person per year. • Improved health and quality of life through reduction of risk factors • Fewer on-the-job accidents • Reduced premature retirement • Decreased health care utilization • Stabilized health benefit costs Benefits for community: • Increased opportunity for support from co-workers and environment • Complements and reinforces national and regional public health initiatives • Reduced absences • Reduced illness and accidents • Reduced medical costs Benefits for employers: • Increased worker productivity • Informed, health care costconscious workforce • Positive public relations • Recruitment tool Association of Washington Cities • Reduced disability claims • Increased morale via management's interest in their health and wellbeing • Increased worker morale 12 • Opportunity for cost savings via: • Reduced absenteeism • Contributes to establishing health as a norm • Provides a model for other area organizations • Improves quality of life of citizenry • Helps control (and possibly reduce) the economic and social burden on all tax payers of premature death and disability The worksite is also an ideal location for wellness activities from the perspective of program effectiveness. Since adults spend most of their waking hours at work, what better place to reach them? Lifestyle change is a slow, incremental process. It requires information, commitment, and support – over time – to be effective for most people. Among the many documented advantages of offering wellness programs to people where they work are: “The commitment of the City Council and members of management has made the City’s • The high rate of voluntary participation program active and alive • The ability to work with large groups of people over an extended period of time with great potential for • The presumption by employees that if their employer sponsors a program it must be valuable future growth and an • The perception of the programs by employees as an additional employee benefit ever-increasing level of • The opportunities for mass communication participation.” • The opportunities to create social support for behavior change on an individual and group basis Karen Sires, Human Resources Manager and • The potential for economic return to the employer and the employee – a healthier employee spends less out of pocket. Wellness Coordinator, City of Pullman It's clear that wellness at the worksite is a trend that has yet to reach its full potential. It's also clear that wellness at work is a win/win situation. Employers win employee appreciation, an enhanced community and professional reputation and a healthier bottom line. Employees win better health and an overall higher quality of life. Chapter 1 Workplace Wellness Planner 13 What is a workplace wellness program? Workplace wellness programs are an organized effort intended to foster awareness, influence attitudes, and identify alternatives, so that individuals can make informed choices and change their behavior to reach an optimal level of wellness. (Remember that wellness is an intentional choice of lifestyle characterized by personal responsibility, balance and maximum personal enhancement of mind, body and spirit.) Dr. Bill Hettler, co-founder of the National Wellness Institute has identified six dimensions of wellness which extend far beyond the well-known physical aspects of health. The six dimensions are described below. • The physical dimension covers the most commonly understood aspects of health including physical activity, diet, nutrition, smoking, drugs, and alcohol consumption. Physical wellness is characterized by the belief that it is better to consume foods and beverages that enhance good health rather than those which impair it. • The spiritual dimension recognizes our search for meaning and purpose in human existence. Spiritually well people believe it is better to live each day in a way that is consistent with their values and beliefs than to do otherwise and feel untrue to themselves. • The intellectual dimension explores issues of problem-solving, creativity and learning. People who are intellectually well feel it is better to stretch and challenge their minds with intellectual and creative pursuits than to become self-satisfied and unproductive. • The social dimension encourages contributing to one’s environment and community. Social wellness is modeled by living in harmony with others and our environment rather than in conflict with them. • The emotional dimension recognizes awareness and acceptance of one’s feelings. It includes the degree to which a person feels positive and enthusiastic and is able to cope with stress. • The occupational dimension recognizes the need for personal satisfaction and enrichment in one’s life through work. Occupational wellness may be found by choosing a career which is consistent with personal values, interests and beliefs. What should your wellness program look like? It is natural to look around at other programs and wonder, “What should our program look like?” and “What is a successful program?” It would be nice if there were perfect, straight forward answers to these questions. However, nothing is ever that simple. The process for developing a successful program is the same for everyone, but no two programs will ever end up looking exactly the same. 14 Association of Washington Cities To achieve the kind of success documented in the studies referenced earlier in this chapter, a wellness program needs the following elements: • Detailed plan with a committed leader • Senior-management and elected official commitment to make it work • Coordinated effort among departments • Solid foundation of policies, programs, and an environment that provides health awareness, education and behavior change opportunities for employees Program planning Wellness programs can include anything that helps people identify their personal health risks to support lifestyle changes. Since the range of potential wellness programs is enormous, it helps to have a systematic way to think about program planning. The figure on the right provides a conceptual program planning model that illustrates the structural components of the planning process. Program Planning Model Components of the Planning Process Foundation • Gain management support • Create supportive work environment • Form a wellness committee • Set policies • Create a mission statement • Involve employees Assessment Design • Inventory your internal resources • Locate other wellness program coordinators • Explore AWC resources • Inventory your external resources • Review data • Identify needs, interests & risks DELIVERY ASSESSMENT DESIGN FOUNDATION • Establish program goals and objectives • Document a plan • Know your audience • Develop a means of evaluation • Select activities & interventions • Establish a budget • Create a timeline and schedule • Select vendors and materials • Delegate responsibilities Delivery • Promote the program • Provide incentives • Launch the program • Facilitate the activities • Evaluate progress and outcomes Chapter 1 Workplace Wellness Planner 15 “Health is obviously so much more than a diseasefree interlude. To be healthy is to have a body toned to its maximum performance potential, a clear mind exploding with wonder and curiosity, and a spirit happy and at peace with the world.” The AWC Well City Standards AWC has identified nine steps that are necessary to building a workplace wellness program that has impact. They are expressed as the AWC WellCity Standards and serve as chapter headings for the remaining nine chapters in this Planner. If you follow these standards as guidelines, you will see your program take shape as you build upon a strong foundation with careful assessment and design steps before moving on to implementation and delivery. Keep in mind that as you build your program, you may not move through the chapters sequentially, one at a time. Some chapters build on each other, while others work together simultaneously. As you explore each element of the program planning process you find yourself moving back and forth through the chapters. AWC WellCity Standards 1. Developing Policies & Procedures 2. Gaining Management Support 3. Creating a Wellness Committee Dr. Patch Adams 4. Weaving Your Wellness Network 5. Assessing Program Needs 6. Building an Infrastructure of Health 7. Forming an Operating Plan 8. Planning Activities and Interventions 9. Evaluating Progress & Outcomes These standards cover the four components of AWC’s program planning model which is highlighted at the beginning of each chapter.You’ll notice some chapters play a roll in multiple components. Within each chapter you’ll find instructions, assessments, guidelines, resources, and worksheets designed to help you create a successful workplace wellness program. 16 Association of Washington Cities Exhibit 1-1 Workplace Wellness Program Resources Leadership for Healthy Communities www.activelivingleadership.org Centers for Disease Control Healthier Worksite Initiative Policies, toolkits, resources, program design. www.CDC.gov/hwi National Wellness Institute www.nationalwellness.org Professional Assisted Cessation Therapy (PACT) Employers’ Smoking Cessation Guide: Practical Approaches to a Costly Workplace Problem www.endsmoking.org Partnership for Prevention www.prevent.org Wellness Councils of America www.welcoa.org Chapter 1 Workplace Wellness Planner 17 18 Association of Washington Cities

![[subject line] You're invited to share the health](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008613453_1-c65c31d0738aa28772fa551d6f3e1bcf-300x300.png)