Ritual and Myth in Native American Fiction

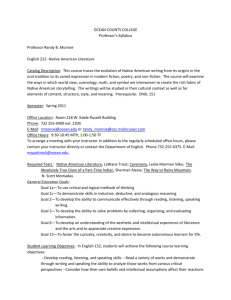

advertisement