Housing Law - Practising Law Institute

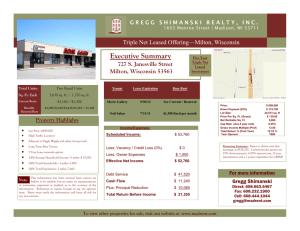

advertisement