AND

88

8

SER

V

H

NC

THE BE

ING

BA

R SINCE 1

Web address: http://www.nylj.com

VOLUME 235—NO. 85

WEDNESDAY, MAY 3, 2006

COOPERATIVES

AND

CONDOMINIUMS

BY RICHARD SIEGLER AND EVA TALEL

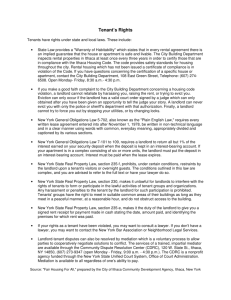

The Warranty of Habitability, 2006

T

hirty-one years after its codification as

New York Real Property Law (RPL)

§235-b, the warranty of habitability

remains an important protection for

residential tenants.1

Under this statute, every residential lease

contains an implied, nonwaivable warranty that

the premises are fit for human habitation and

will provide the essential functions of a residence, and that occupants will not be subjected

to conditions that are dangerous, hazardous or

detrimental to life, health or safety.

Courts generally enforce this statute by

awarding rent abatements for unfit conditions

to rental tenants, including co-op apartment

owners whose proprietary lease creates the

requisite landlord-tenant relationship.2 The

extent of the abatement is determined by

weighing the severity of the breach, its duration

and the effectiveness of the landlord’s efforts

to cure the condition.3 The warranty does not

permit a tenant to recover for damage to

personal property or for personal injury resulting

from a breach.4 And the warranty is inapplicable

to condominium units, where no landlordtenant relationship exists.5

In previous articles dealing with the

warranty of habitability, we examined various

conditions and discussed whether they constitute a breach, including water damage,6 inoperable elevators in a luxury building,7 and most

recently, noise.8

This article picks up where the others left off,

examining the warranty in light of new case

law and legal trends affecting rental and

co-op apartments.

Mold and Dust

Mold and dust conditions may result in a

violation of the warranty of habitability.9

Recent case law suggests that courts will look

to the effect of the mold condition on the

occupant, not the levels of mold in the apartment, in determining whether there is a breach.

In 360 West 51st Street v. Cornell,10 the court

Richard Siegler is a partner in the firm of

Stroock & Stroock & Lavan and is an adjunct

professor at New York Law School. Eva Talel is

also a partner in Stroock & Stroock & Lavan,

specializing in litigation involving co-ops and

condominiums. David Koshers, a New York

Law School student, assisted in the preparation of this

article. Disclosure: Stroock & Stroock & Lavan is

counsel to the Real Estate Board of New York.

Richard Siegler

Eva Talel

summary dismissal of the Beck complaint, holding that there was no basis for the tenant’s claim

that the landlord had an “ongoing duty to

monitor the plaintiff ’s apartment for the

possible development of environmental hazards.”14 Water damage and brown stains on the

wall did not amount to constructive notice of a

mold condition. Because the tenant moved out

of the apartment before the landlord had a

reasonable opportunity to remediate the mold

condition, the tenant’s claim was dismissed.

Safety and Security Issues

awarded a tenant allegedly sickened by minimal

mold growth a full rent abatement. The tenant

claimed that after the landlord removed debris

and old furniture from basement storage areas,

she began to suffer from rashes, fatigue,

headaches, shortness of breath and was forced to

visit hospital emergency rooms several times.

Faced with conflicting expert testimony on

the adverse health effect of the small amount of

mold found present in the apartment, the court

based its decision on the tenant’s testimony “of

a happy life, excellent health, a lot of physical

activity in the gym and on her bicycle…a

beautiful apartment tastefully decorated…and

then poof, a cloud of dust and spores arose from

the basement and ruined it all.”11 The court held

that, despite the minimal amount of mold, the

effect on the tenant was severe and she was

therefore constructively evicted from the

premises, and awarded her a 100 percent rent

abatement for a period of 6.2 months.

In Beck v. J.J.A. Holding Corp.,12 the

Appellate Division, First Department focused

on the requirement of notice, and held

that actual or constructive knowledge by the

landlord of the mold condition itself was

required before liability could be imposed.

Lower-court decisions had previously suggested

that a landlord could incur liability even if it

had only constructive notice of conditions in

an apartment which might result in a mold

condition, such as water leaks or brown spots on

the walls.13

In Beck, the tenant claimed that as a result

of water damage, mold contaminated her

apartment and she became chronically ill. She

argued that because mold is a foreseeable

consequence of water damage, the landlord,

who had notice of the water damage, breached

the duty to maintain the apartment in a safe and

habitable condition.

A unanimous First Department affirmed

Case law makes clear that residential

landlords have a duty to provide tenants with a

safe premises and the failure to do so, after

notice of a hazard, frustrates the tenant’s ability

to make reasonable use of the premises and

breaches the warranty of habitability.15

In Auburn Leasing Corp. v. Burgos,16 the

landlord rented an apartment to tenants who

began to deal drugs from the apartment on a

24-hour basis. Repeated complaints from

occupants of the adjacent apartment were

initially ignored, but the landlord eventually

commenced a summary proceeding seeking to

evict the drug-dealing tenants, by which time

the adjacent tenants had moved out. The landlord sought to recover rent for the balance of

the adjacent tenants’ lease term and the court

rejected the claim, holding that the landlord

breached the warranty by failing, after notice,

to protect the tenants, and the tenants had

therefore been constructively evicted and

owed no rent. The landlord’s commencement

of a summary proceeding was “too little and

too late.”17

Landlords are also on constructive notice

that a defective door or lock may lead to an

assault or theft.18 When landlords provide locks

and doors, they assume a duty to maintain

them in working condition. When a landlord is

on notice that locks or doors have become

inoperable and makes no repairs, the landlord

is deemed to have breached the warranty

of habitability.19

However, where a tenant is assaulted or

burglarized but cannot demonstrate that the

landlord’s security measures are inadequate,

there is no breach of the warranty. In Estate of

Hortense Klein v. Beekman Tenants Corp.,20 a

tenant was assaulted and her co-op apartment

burglarized when an assailant gained entry to

her apartment. The court found that the tenant

failed to show that the co-op knew or should

have known of the probability of conduct that

NEW YORK LAW JOURNAL

would likely endanger her safety, and there was

no evidence of a history of prior criminal

activity in the building. Relying on the Court

of Appeals’ decision in James v. Jamie Towers

Housing Co.—holding that “by providing

locking doors, an intercom service and 24-hour

security, [landlord] discharged its common-law

duty to take minimal security precautions

against reasonable foreseeable criminal

acts”21—the court summarily dismissed the

tenant’s claim.

In Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village

Tenants v. Metropolitan Life Insurance and

Annuity Co.,22 the landlord sought to install a

security system to update the 50-year-old existing system; metal keys would be replaced by

“cardkeys” sensed by a reading mechanism at

the lobby entrances. The tenants’ association

objected, claiming, among other things, a

breach of the warranty of habitability because

the new security plan would create a “hardship”

—periodic renewal of the cards and taking

identification pictures would allegedly create a

burden on residents and guests and prevent

family members from visiting and checking on

tenants with potential medical emergencies.

The court rejected the tenants’ challenge,

holding that the inconveniences alleged did not

deprive the tenants of the essential functions

of a residence.

Rodents and Bedbugs

Where a residence is infested with insects

or rodents, creating a threat to the health and

safety of the occupants or intolerable living

conditions, courts have found a breach of the

warranty of habitability.23

In Elijah Jermaine, LLC v. Boyd,24 the court

found a breach of warranty based upon

unremedied rodent infestation and other defective conditions in an apartment. The landlord

had notice of the conditions and took no corrective action. The tenant was awarded a 15

percent rent abatement for a period of seven

months. Building management must take

corrective steps commensurate with the gravity

of the infestation. Where the landlord’s steps

were ineffectual to remedy the infestation,

the tenant was awarded a 100 percent rent

abatement for three months.25

In addition to common rodents and vermin,

bedbugs have resurfaced as a problem in New

York City. In Ludlow Properties LLC v. Young,26

the court found that the presence of such bugs

notwithstanding the landlord’s extermination

efforts, created an intolerable condition and

awarded the rental tenant a 45 percent rent

abatement for a period of seven months.

Similarly, in Jefferson House Associates, LLC v.

Boyle,27 the court awarded the rental tenant a 50

percent rent abatement for six months, and a 20

percent abatement thereafter until the problem

was remedied.

Lead-Based Paint

Lead-based paint was frequently used to paint

apartment interiors in buildings erected before

1978. Courts have found a breach of the

warranty of habitability where the landlord is on

notice of the presence of lead-based paint in a

dwelling, such that it creates a dangerous or

hazardous condition for its occupants.28

In 2004, The New York City Council

WEDNESDAY, MAY 3, 2006

enacted the Childhood Lead Poisoning

Prevention Act (the act).29 This requires

landlords to abate lead paint hazards in

apartments and common areas of buildings

where children under the age of seven reside.

The act also puts the landlord on constructive

notice of any lead paint hazard condition within an apartment that is occupied by a child

under the age of seven. The act permits responsibility for compliance to be allocated by

agreement between a co-op apartment owner

and the co-op corporation. Preparation of such

agreements and compliance by a co-op with

the act warrants consultation with a knowledgeable source.30

Other Issues

In Port Chester Housing Authority v. Mobley,31

a quadriplegic rental tenant in a handicapped

apartment sued the landlord for breach of the

warranty of habitability for failure to provide a

roll-in shower. The Appellate Term, First

Department, found no breach, holding that

the warranty does not make the landlord a

guarantor of every tenant amenity, but only

protects against conditions which materially

and adversely affect the health and safety of a

tenant, or deficiencies that deprive a tenant of

the essential functions of a residence.

In Franken Builders Inc. v. Ciccone,32 a landlord sought to terminate a lease for the rental

tenant’s failure to comply with a lease requirement that 80 percent of the apartment’s floor

area be covered with carpeting. The tenant

claimed that she had an allergic/asthmatic

condition and having carpeting in her residence

would create a dangerous or hazardous

condition, thereby breaching the warranty of

habitability.

The court rejected the tenant’s claim,

holding that landlord’s carpet requirement did

not create a harmful condition or deprive the

tenant of the essential functions of a residence.

Instead, the rule served a legitimate and reasonable noise control purpose. The landlord was

awarded possession of the apartment.

Conclusion

Recent case law demonstrates the willingness

of New York courts to apply the statutory

warranty of habitability to cover new and

evolving conditions, such as mold and leadbased paint hazards. Co-op boards and managing agents should therefore be vigilant to ensure

that unsafe or dangerous living conditions are

promptly remediated. To protect the co-op

corporation from unfounded breach of warranty

claims, management should maintain records

of complaints received, remediation efforts

made, the results achieved, and the difficulty (if

any) in obtaining access to the apartment

in question.

••••••••••••••

•••••••••••••••••

1. N.Y. Real Property Law §235-b (McKinney Supp. 2006).

2. Courts are mindful that, because of the unique nature of

co-ops, the warranty of habitability cannot be applied to coops in precisely the same way as it is applied to landlords of

rental property. A co-op board is both a landlord and representative of the shareholders who are occupants of the co-op

property, and must balance individual and collective interests.

Therefore, under the business judgment rule, when faced with

a claim for breach of the warranty arising out of a board

action, courts should defer to the decisions of co-op boards

where the challenged action is taken in good faith, within the

board’s authority and in furtherance of the co-op’s interests, as

a whole. See, e.g., 29-45 Tenants Corp. v. Rowe, NYLJ, Jan. 8,

1992, at 23, col. 4 (Civ. Ct. N.Y. Co.) (tenant deprived of terrace use to accommodate building repairs cannot recover for

breach of the warranty); 315-321 Eastern Parkway

Development Fund Corp. v. Wint-Howell, 9 Misc3d 644 (Civ.

Ct. Kings Co. 2005) (tenant deprived of use of certain

kitchen and bathroom facilities because of building-wide renovation project cannot recover for breach of the warranty).

3. Park West Management v. Mitchell, 47 N.Y. 2d 316

(1979), cert. denied, 444 U.S. 992 (1979).

4. 40 Eastco v. Fischman, 155 A.D.2d 231 (1st Dept. 1989);

Elkman v. Southgate Owners Corp., 233 A.D.2d 104 (1st Dept.

1996).

5. Frisch v. Bellmarc Management, Inc., 190 A.D.2d 383

(1st Dept. 1993), confirmed in Linden v. Lloyds Planning

Service, Inc., 299 A.D.2d 217 (1st Dept. 2002).

6. See 750 Kappock Apartments Corp. v. Daly, NYLJ, April

9, 1997, at 29, col.1 (Civ. Ct. Bronx Co. 1997). See also

Richard Siegler, “An Update of the Warranty of Habitability,”

NYLJ, July 1, 1998, at 3, col.1.

7. Richard Siegler and Eva Talel, “Another Look at the

Warranty of Habitability,” NYLJ, March 3, 2004, at 3, col. 1,

discussing Solow v. Wellner, 86 N.Y.2d 582 (1995).

8.Richard Siegler and Eva Talel, “Noise and the Warranty

of Habitability,” NYLJ, March 1, 2006, at 3, col.1.

9. 106 East 19th Associates v. Berg-Munch, NYLJ, July 3,

2001 at 21, col. 5 (App.Term 1st Dept. 2001).

10. NYLJ, Sept. 6, 2005, at 18, col.1 (Civ. Ct. N.Y. Co.

2005).

11. Id.

12. 12 A.D.3d 238 (1st Dept. 2004).

13. See, e.g., Litwack v. Plaza Investors, NYLJ, Dec. 1, 2004,

at 23, col.1 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 2004).

14. Beck, 12 A.D.3d at 240. For a comprehensive discussion of mold remediation and legal liability, see Richard

Siegler and Eva Talel, “Dealing with Mold: ‘Beck,’ Health

Hazards, Risk Management”, NYLJ, July 6, 2005, at 3, col. 1.

15. 610 W. 142nd Street Owners Corp. v. Braxton, 137

Misc.2d 567, 568 (Civ. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1987), modified on other

grounds, 140 Misc.2d 826 (App. Term 1st Dept. 1988).

16. 160 Misc.2d 374 (Civ. Ct. Queens Co. 1994).

17. Id. at 375. See also, U.S. Brownsville II, HDFC v.

Nelson, 2004 NY Slip Op 50466U (Civ. Ct. Kings Co. 2004).

18. 610 W. 142nd Street Owners, 137 Misc.2d 567.

19. Brownstein v. Edison, 103 Misc.2d 316 (Sup. Ct. Kings

Co. 1980); Sherman v. Concourse Realty, 47 A.D.2d 134 (2nd

Dept. 1975). See also N.Y. Multiple Dwelling Law §50-a[3]

(McKinney 2001).

20. Estate of Klein v. Beekman Tenants Corporation,

No.118720/02 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. Nov. 22, 2005). While the

tenant’s claim in this case was based on the co-op’s alleged

negligence, the court’s analysis, and dismissal of the tenant’s

claims, would have been the same under a breach of warranty

theory. See, e.g., Phillips v. Czajka, NYLJ, Nov. 25, 2005, at

19, col. 1 (Civ. Ct. Kings Co. 2005).

21. 99 N.Y.2d 639 (2003).

22. NYLJ, July 19, 2004, at 19, col. 1 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co.

2004).

23. Kenmart Realty v. Alhalabi, NYLJ, Dec. 19, 1994 at 32,

col.1 (City Ct. of Yonkers, Westchester Co.) (persistent rat

infestation warranted a 100 percent rent abatement).

Northwood Village v. Curet, NYLJ, Nov. 27, 1998 at 1, col.1

(2nd Jud. Dept. Suffolk Co.) (100 percent rent abatement for

landlord’s failure, inter alia, to cure vermin and rodent infestation).

24. 2004 NY Slip Op 51322U (App. Term 1st Dept. 2004).

25. Kenmart Realty, NYLJ, Dec. 19, 1994 at 32.

26. 4 Misc. 3d 515 (Civ. Ct. N.Y. Co. 2004).

27. 2004 N.Y. Slip Op. 50225 (U).

28. Edgemont Corporation v. Audet, 170 Misc.2d 1040

(App.Term 2nd Dept. 1996) (extremely elevated levels of

lead-laden dust in a rental apartment constituted a threat to

the health of tenant’s daughter and rendered apartment unusable); Chase v. Pistolese, 190 Misc.2d 477 (City Ct. of

Watertown, Jefferson Co. 2002) (landlord breached warranty

of habitability by renting apartment containing lead-based

paint to tenant’s family which included one young and one

unborn child, with knowledge that paint would be exposed by

proposed remodeling work).

29. NYC Admin. Code §27-2056, et seq. (2005 Supp.)

30. See, e.g. Real Estate Finance Journal, Summer 2005 at

86, “New York City Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention

Act,” Robert G. Koen Interview with Eva Talel.

31. 2004 N.Y. Slip. Op. 24416.

32. NYLJ, Feb. 3, 2004, at 20, col. 1 (City Ct. of New

Rochelle, Westchester Co. 2004).

This article is reprinted with permission from the May

3, 2006 edition of the NEW YORK LAW JOURNAL.

© 2006 ALM Properties, Inc. All rights reserved.

Further duplication without permission is prohibited.

For information, contact ALM, Reprint Department

at 800-888-8300 x6111 or www.almreprints.com.

#070-05-06-0004