gonzaga law review - Gonzaga University School of Law

advertisement

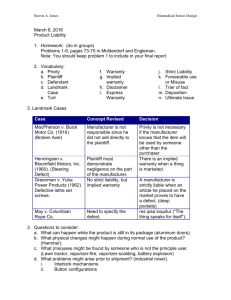

GONZAGA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 5 SPRING 1970 NUMBER 2 PRODUCTS LIABILITY IN PERSPECTIVE William L. Prosser*t The general idea, as I understand, is that I am to ramble around for awhile on the subject of products liability-where we are, and where we are going. I am well aware that many of you have afternoon engagements, and if anybody wants to walk out at any time-in fact, if whole blocks of the audience wish to walk out-I shall fully understand and not be annoyed in the least. So, let us begin. Products liability from the plaintiff's standpoint offers three possible theories of recovery. The first of these is negligence-that the defendant, whoever he may be, retailer, wholesaler, manufacturer, has not used reasonable care in making or marketing the product. This, of course, is an old friend, something that everyone was taught in law school. It goes back to 1916, when that rare phenomenon occurred-a Scotsman bought what was then an expensive motor car. The case fell into the hands of Judge Cardozo of the Court of Appeals of New York. In MacPherson v. Buick Motor Company,' it was held that the manufacturer owed a duty of reasonable care to the ultimate consumer or user of the car. That was * Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of Law. t This text is derived from an address delivered by Dean Prosser to the Spokane County Bar Association at Spokane, Washington, on November 21, 1969. The text conforms to the spoken words of Dean Prosser, with the following changes and additions: (1) Such technical alterations in the text as have been necessary to transcribe the spoken words to the pages of the Review have been made. (2) Where appropriate, footnote citations have been added by the editors. For these footnotes the speaker is in no way responsible. For Dean Prosser's comprehensive treatment of the development of the law of products liability, see Prosser, The Assault Upon the Citadel, 69 YALE L.J. 1099 (1960), and Prosser, The Fall of the Citadel, 50 MINN. L. Rav. 791 (1966). See also PRossER, Tna LAW OF ToRTs 672-85 (3d ed. 1964). 1 217 N.Y. 382, 111 N.E. 1050 (1916). GONZAGA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 5:157 gradually extended and expanded in ways that you are all familiar with. Among other things, it was extended to include injuries to mere bystanders2 and collisions with other vehicles,8 and it became quite well established. I think Mississippi was actually the last state to accept the negligence cause of action without privity of contract, 4 and actually it never did accept it-it jumped right over it to strict liability.5 But I have no doubt that Mississippi would accept liability for negligence. This is still a very live cause of action from the standpoint of the plaintiff. It has been largely replaced by the other two theories-warranty and strict liability in tort. Nevertheless, it is still available in every jurisdiction; and because these other theories are still relatively new and lawyers are not very sure of their ground, they tend to plead and attempt to prove negligence. Of course, if they can succeed in proving negligence, this is likely to have its effect on the jury in terms of the damages and the tendency to give the plaintiff, rather than the defendant, the breaks. For that reason alone, if nothing else, it is quite likely that negligence will continue to be pleaded and attempted to be proved for a great many years to come. It is by no means a dead letter. There are also a few small particulars in which negligence quite possibly will accomplish something which the strict liability theories will not. One of them is where a product is sold which is in no way defective-it is well made and is what it purports to be-there is absolutely nothing wrong with it as a product. But the seller of that product is under a duty to give directions for its use, or warnings as to its dangers, and if he fails to do so you have, strictly speaking, neither a case of strict liability nor warranty, but a case of the seller's negligence. Consequently, where directions for use and duty to warn are in the picture, as they are to an increasing extent nowadays, negligence has been, and still is, the favorite cause of action. Another feature is that negligence will always protect the person I have called by the generic name of "bystander"-the man who has not purchased the product, is not using it, is not consuming 2 See, e.g., Reed & Barton Corp. v. Maas, 73 F.2d 359 (Ist Cir. 1934); McLeod v. Linde Air Products Co., 318 Mo. 397, 1 S.W.2d 122 (1927); Hopper v. Charles Cooper & Co., 104 N.J.L. 93, 139 A. 19 (1927). 3 See, e.g., Sutton v. Diimmel, 55 Wn. 2d 592, 349 P.2d 226 (1960) ; Markel v. Spencer, 5 App. Div. 2d 400, 171 N.Y.S.2d 770 (1958), aff'd on rehearing 5 N.Y.2d 958, 184 N.Y.S.2d 835, 157 N.E.2d 713 (1959) ; Washburn Storage Co. v. General Motors Corp., 90 Ga. App. 380, 83 S.E.2d 26 (1954). 4 For some unaccountable reason Mississippi continued to avoid express acceptance of the MacPherson rule. See PROSSER, THE LAW oF TORTS 661 n.30 (3d ed. 1964), and cases cited therein. Prior to 1962, a similar situation existed in Virginia. Id. This was changed, however, by statute. VA. CODE, 1962 Cum. Supp. § 8:654.3. 5 State Stove Mfg. Co. v. Hodges, 189 S.2d 113 (Miss. 1966), cert. denied, 386 U.S. 912 (1967). Spring, 1970] PRODUCTS LIABILITY it, has nothing to do with it, but is simply around in the vicinity of its probable use. The man on the sidewalk who is hit when the steering gear of the car breaks and the automobile comes up and rams him in the rear-that sort of fellow.' Since about 1918 he has been allowed to recover for negligence. As I am going to mention later, there is considerable dispute at the present time as to whether he has any cause of action in strict liability. If you happen to be in a state where he has not, or where there is doubt about it, then negligence is the obvious choice of action, provided you can prove it. Negligence is aided by res ipsa loquitur if the plaintiff can prove that he was injured by the product, that there was something wrong with the product, and if he can trace that defect in the product back into the hands of the particular seller he is suing. If he can accomplish these things he usually makes out a res ipsa loquitur case, and if does make out a res ipsa loquitur case, as all of the trial lawyers within the sound of my voice are well aware, the jury almost always returns a verdict for the plaintiff. If the plaintiff gets that far, it is a rare phenomenon, although of course not an unknown one, that the jury brings in a verdict for the defendant. So much for negligence. The second cause of action is the old sales action for breach of warranty. This began as a matter of direct warranties between people who had dealt with one another by contract-a warranty on the product from the seller to his immediate buyer. It began as a matter of express representations about the product. With a long lapse of time, over a great many centuries, implied respresentations were worked out. The whole thing was between the immediate parties and was codified under the Uniform Sales Act, now replaced, of course, by the Uniform Commercial Code in practically all jurisdictions. Warranty was a matter of contract, and in the absence of privity of contract there could be no cause of action for breach of warranty. In 1913, on the heels of prolonged agitation about defective food, three states7 proceeded to throw overboard the ancient requirement that for an implied warranty there had to have been a contract between the parties. Those states were Washington, which led off and was the 6 See, e.g., Gaidry Motors Fox Bros. Buick Co., 196 Wis. Zahn, 265 F.2d 729 (8th Cir. Weirton Bus Co., 216 F.2d 404 7 Washington, Kansas and v. Brannon, 268 S.W.2d 627 (Ky. 1954); Flies v. 196, 218 N.W. 855 (1928); cf. Ford Motor Co. v. 1959) (passenger in car); Carpini v. Pittsburgh & (3d Cir. 1954) (passenger in bus). Mississippi. GONZAGA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 5: 157 first in the country to shed the privity requirement;8 then followed Kansas9 and Mississippi.' Starting with these three states, you began to get the development of a special rule applicable to sellers of food. Whether they were manufacturers or dealers, anyone who sold food was held to a type of special warranty that it-was fit to eat. This special rule gradually extended until by, let us say, 1955, it was the predominant rule in the United States. It applied without any privity of contract between the parties. If the defendant manufactured food-if for instance, he bottled Coca Cola-and it passed through the hands of a distributor and a retailer to a purchaser, and that purchaser gave it to his fiancee, and it turned out that there was a dead mouse in the bottle, the warranty was held to run to the ultimate consumer of the product. Now this was a good deal of a freak. Actually, something like twenty-nine different theories were evolved at one time or another to sustain this conclusion," that there was liability without negligence and without privity of contract. They ranged from third party beneficiary contracts, to fictitious agencies of the retailer to sell for the manufacturer or buy for the consumer, and other such inventions. They were, for the most part, thoroughly unsound and invented for the sole purpose of justifying the result. Finally in, I think, 1927, the Mississippi court came up with the theory of an implied warranty running with the goods from the manufacturer to the consumer-by analogy, to a covenant running with the land.' 2 Ever since then the courts that have talked warranty have relied either on that theory or, more lately, on the theory of a direct warranty implied by the law directly from the manufacturer to the consumer. At one time this was evidently the coming thing. The warranty theory has several things in its favor. One is its recognition in the Uniform Commercial Code, 3 which no longer insists on privity of contract and which has been quite willing to extend the warranty to plaintiffs who have not dealt with the defendant at all. Consequently, you have a statute to back it up. In the second place, warranty has various possibilities in terms of dealings between the parties. You can, for instance, have express representations made by the manufacturer of an automobile which are intended to be passed on, and are in fact passed on, to the ultimate purchaser of the car. Here Mazetti v. Armour & Co., 75 Wash. 622, 135 P. 633 (1913). 9 Parks v. G. C. Yost Pie Co., 93 Kan. 334, 144 P. 202 (1914). 10 Jackson Coca-Cola Bottling Co. v. Chapman, 106 Miss. 864, 64 So. 791 (1914), 11 See Gillam, Products Liability in a Nutshell, 37 ORE. L. Rav. 119, 153-55 (1957), which assembles no less than twenty-nine such theories. 12 Coca-Cola Bottling Works v. Lyons, 145 Miss. 876, 111 So. 305 (1927). 18 See UNiFORM COMMERacA. CODE §§ 2-314 and 2-315. 8 Spring, 1970] PRODUCTS LIABILITY again, the leading case was from Washington-Baxter v. Ford Motor Company.' 4 In this case the Ford Motor people advertised that the glass in their windshields was shatterproof-they call it safety glass now days. This claim proved to be a grave mistake. The Ford people had advertised shatterproof glass and the plaintiff, as he testified, bought the car in reliance on that representation. He was injured when a stone struck and shattered the windshield. This express representation was held to be an express warranty, running to the consumer, which made the defendant liable to him. On rehearing, the court, much bothered by the various complications introduced by the Uniform Sales Act, proceeded to put the thing on a strict liability basis for innocent misrepresentation, an area in which the Washington court had already gone pretty far in other cases. The result is that as to express warranties, there were two possibilities: first, the warranty under the Sales Act, 5 and second, strict liability for innocent misrepresentation. By 1955 this had become the prevailing view in food cases. For a long time there had been a lot of agitation from the professors, to whom nobody paid much attention-a fate which professors have often suffered, and sometimes deservedly so. The professors had been agitating to throw overboard the limitation to food and drink and to extend this thing to other products. It wasn't until 1956 that the Michigan court led off in doing so. The case was Spence v. Three Rivers Builders & Masonry Supply, Inc.,"6 where the plaintiff bought from a retailer cinder building blocks manufactured by the defendant and built his house with them. Now cinder building blocks are not food, and they are not inherently dangerous; they are perhaps the most uninspired product you could think ofthere is nothing very romantic or interesting about them. But they collapsed, and so did the plaintiff's house, and the plaintiff brought suit. The case fell into the hands of Justice Voelker, author of what was once a popular best-seller, Anatomy of a Murder. Justice Voelker held the defendant liable in warranty-implied warranty to the ultimate consumer without privity of contract. He cited practically no cases; and there were those who said that as an opinion writer, Justice Voelker was a very good movie scenario creator, but no great legal authority. Nevertheless, this started the thing off. By 1960, some eight jurisdictions had followed the Spence case-the handwriting was on the wall as to where it was all going. 7 14 168 Wash. 456, 12 P.2d 409, 88 A.L.R. 521, aff'd on rehearing, 15 P.2d 1118 (1932). 15 See UNIFORm SALES AcT § 15. 16 353 Mich. 120, 90 N.W.2d 873 (1958). 17 Actually, through 1960, eleven jurisdictions had followed Spence. The pre-1960 cases included: B. F. Goodrich Co. v. Hammond, 269 F.2d 501 (10th Cir. 1959) (ap- GONZAGA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 5:157 The Restatement of Torts (Second) was actually drafted three times in order to keep up with the progress of the whole story. Originally it was drafted to apply only to food and drink. Then it was revised to include products for what was called intimate bodily use such as clothing, cigarettes, and other such things that touched the person but which were not for internal consumption. Finally, it was expanded to all products.' 8 This was in three consecutive years. Being very much troubled about this hybrid warranty, the Restatement got rid of it. What has happened since is that warranty continued to gain; at one time about half the jurisdictions of the United States found an implied warranty on products other than food and drink. But in the meantime, the third possible cause of action had erupted into the picture. It started when the Restatement of Torts, bothered by warranty, stated the defendant's liability in ordinary tort terms, without making use of the word "warranty" at all. It said, in effect, that anyone who markets a product, expecting that it will be passed into the hands of an ultimate user or consumer without any change in its condition, and who markets it in a condition unreasonably dangerous to the user or consumer, is liable for personal injuries to the user or consumer even without privity of contract or any negligence on the part of the defendant. Now this actually stated nothing more than had been stated in the warranty cases. But it got rid of the word "warranty," and with it all sorts of contract limitations which had hedged that word about. Among the limitations were possible disclaimers, the requirement of reliance-that the ultimate purchaser must rely upon the representation, or rely upon the defendant-and so on. The first case to attempt to deal with this new development, if you can call it that, was in California-Greenman v. Yuba Power plying Missouri & Kansas law); Magee v. General Motors Corp., 124 F. Supp. 606 (W.D. Pa. 1954), aff'd, 220 F.2d 270 (3d Cir. 1955); Hinton v. Republic Aviation Corp., 180 F. Supp. 31 (S.D. N.Y. 1959) (applying California law); Beck v. Spindler, 256 Minn. 543, 99 N.W.2d 670 (1959); Jarnot v. Ford Motor Co., 191 Pa. Super. 422, 156 A.2d 568 (1959); Continental Copper & Steel Indus. v. "Red" Cornelius, Inc., 104 So. 2d 40 (Fla. App. 1958). In addition, those cases decided in the year 1960 included: Conlon v. Republic Aviation Corp., 204 F. Supp. 865 (S.D. N.Y. 1960) (applying Michigan law); Taylerson v. American Airlines, 183 F. Supp. 882 (S.D. N.Y. 1960); McQuaide v. Bridgeport Brass Co., 190 F. Supp. 252 (D. Conn. 1960) (applying Pennsylvania law); Siegel v. Braniff Airways, 204 F. Supp. 861 (S.D. N.Y. 1960) (applying Texas law); Peterson v. Lamb Rubber Co., 54 Cal. 2d 339, 5 Cal. Rptr. 863, 353 P.2d 575 (1960); Pabon v. Hackensack Auto Sales, Inc., 63 N.J. Super. 476, 164 A.2d 773 (1960); Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors, 32 N.J. 358, 161 A.2d 69, 75 A.L.R.2d 1 (1960); General Motors Corp. v. Dodson, 47 Tenn. App. 438, 338 S.W.2d 655 (1960). 18 See RESTATEMENT (SECOND) Or ToRTs § 402A (1965). Spring, 1970] PRODUCTS LIABILITY Products, Inc. 9 The defendant made a combination power tool called a "Shop-Smith," which could be used as a lathe, a saw, a plane, all sorts of things-it would do everthing but shine your shoes. It was sold through a dealer and ultimately reached the plaintiff. While the plaintiff was operating the machine as a lathe, it let fly a piece of wood that hit him in the head and injured him. He brought suit, and what he encountered immediately was the fact that he had given no notice to the defendant of any breach of warranty within the required time of the Uniform Sales Act. The defendant tried to escape liability on the ground of lack of notice. Justice Traynor said, in effect, that this was not a case of warranty, but rather a case of ordinary strict liability in tort, and he proceeded to rely on the Restatement theory. In other words, he threw overboard warranty, he threw overboard the notice requirement, and, by implication, he threw overboard disclaimers and all other such things that affected warranty. Warranty never had been anything but a rather transparent device to accomplish strict liability anyway, and in that respect, this was a clear-cut development. It was, of course, not a popular one with the defendants who clung to such things as notice of breach of warranty, disclaimers, and the like. Nevertheless, Traynor's opinion has been followed. At the last count that I have made, and this is not very up-to-date, there were some thirty-four jurisdictions which had accepted this theory of strict liability in tort.20 There is no doubt that this is the coming thing in law, not only of the present but also of the immediate and distant future. Those who do not like it, and many defense attorneys do not, will have to live with it for a long time to come. Now, talking mainly about strict liability in tort, I should like to spend the rest of my time here discussing two or three problems which, to me at least, are the more or less unsolved questions-the difficult questions-surrounding liability without negligence and without privity between a seller of products and the ultimate consumer or user, or anyone else. Actually, a great many questions have arisen, but most of them have been .rather simple 19 59 Cal. 2d 57, 27 Cal. Rptr. 697, 377 P.2d 897 (1963). 20 At last count there were only seven states not applying strict liability either as a warranty or outright in tort: Idaho, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Utah and West Virginia. The states most recently making the change-over were Rhode Island, Alaska, New Hampshire and North Carolina; see Klimas v. Int'l Tel. & Tel. Co., 297 F. Supp. 937 (D. R.I. 1969) (federal court guessing at state law) ; Clary v. Fifth Ave. Chrysler Center, Inc., 454 P.2d 244 (Alas. 1969) ; Buttrick v. Arthur Lessard & Sons, Inc., 260 A.2d 111 (N.H. 1969); Tedder v. Pepsi-Cola Bottling Co. of Raleigh, 270 N.C. 301, 154 S.E.2d 337 (1967) (limited recognition). GONZAGA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 5:157 to solve, and have been solved by such a mass of decisions that there is no longer much of a problem. For example, there is the question of what defendants this would apply to. The answer seems fairly clear that it applies to any defendant who is engaged in the business of selling such a product and does sell it. The manufacturer, the wholesaler, the retailer, anyone in the business-this is a merchant's liability. It does not apply to anyone who is not in the business of selling-a housewife who sells a jar of jam to her neighbor is not going to be held strictly liable. Nor is the private individual who trades in his car for a new model and makes what you might call a sale to the dealer, since he is not in the business of trading in cars. Nor does it apply to the dentist who is using a pneumatic drill which breaks and injures the patient's jaw, since he is not in the business of selling pneumatic drills. Questions like that have been worked out fairly easily, but there are three about which there is trouble. I want to talk about them and offer some guesses as to where we'll wind up. The first question is, "what products?" Well, all kinds of products; there is practically no type of product that has not appeared in a strict liability case. Everything from washing machines to paper cups-it doesn't matter what it is that the defendant is selling. But, there is a somewhat more difficult problem lying behind that. What is to be done about the product which is inherently unsafe-the kind of product which, in our present state of scientific knowledge, and in our present development of the art, we do not know how to make safe, so that it is virtually impossible to produce a safe product of that type? Take, for instance, the sale of blood for transfusion purposes. Blood is commonly-but not so commonly as all that-infected with hepatitis. Of course the person who is given the transfusion comes down with hepatitis, is made seriously ill, and may even die. No known method at the present time, of which I have any information, will permit the seller to produce blood, which has come from donors, which is free from the possibility of hepatitis infection; moreover, no know method will cure it. Now, I may already be outof-date, because I understand that various methods are being experimented with, among them, radiation of the blood which will get rid of the hepatitis infection; but on the other hand, it is likely to do such other damage to the blood that people have been encouraged to go quite slow with it. Nevertheless, such a development may ultimately be the answer to the whole hepatitis problem. Take the situation as it now stands; the seller of the blood is simply unable to provide a safe product by any known methods or means. Now, is he to be liable for breach of warranty, or is he to be Spring, 1970] PRODUCTS LIABILITY strictly liable in tort without any negligence to the ultimate user or consumer? On this the cases have been struggling. The first result was that a good many cases held that there was not even a sale. The blood transfusion was a hospital service; the blood was not actually sold as one sells an automobile in the market-place. It was simply injected as part of a service. 2 Now that is rather nonsensical. The hospitals certainly bill the patient for the blood as a separate item, and certainly title passes to him once it gets into his system. It's as much a part of him as the food which he eats in a restaurant, and nobody has any doubt any more that that is a matter of sale-it is fairly obvious that this was a fiction. Then you began to get blood banks who sold to the hospital, which in turn gave the blood in transfusion to the plaintiff; the plaintiff sued the blood bank because it had definitely made a sale. It had charged for it, and there could be no argument that there was, in fact, a sale. Consequently you had all the arguments of warranty under the Uniform Commercial Code, and you had the problem of strict liability in tort. The courts, a few of them at least, were forced to face up to the proposition: What do you do when you simply cannot make the product safe? Is the seller, as an incident of the enterprise in which he is engaged, to bear the losses, to insure against such losses and pass the whole thing on to the public by means of the insurance premiums? This is a wonderful theory and popular with a great many professors; but actually, it's rather drastic to a lot of fairly small, poor sellers who would be up against the wall. I should think that the cost of the insurance might very well be prohibitive in the case of a small-town blood bank; and if it were not, I think that the price of blood would go up to the point where it would be rather difficult for the patients to obtain. However, that's all speculation. The cases have been virtually unanimous in these blood bank cases in saying that in the absence of negligence-negligence has been found in some cases in not investigating the donors sufficiently-there is no strict liability in tort and there is no breach of warranty. In short, this is just the patient's hard luck. Of course you can go considerably further than the transfusion 21 See White v. Sarasota County Pub. Hosp., 206 So. 2d 19 (Fla. App. 1968); Lovett v. Emory Univ., Inc., 116 Ga. App. 281, 156 S.E.2d 923 (1967); Balkowitsch v. Minneapolis War Memorial Blood Bank, 270 Minn. 151, 132 N.W.2d 805 (1965); Hubbell v. S. Nassau Communities Hosp., 46 Misc. 2d 847, 260 N.Y.S.2d 539 (1965); Koenig v. Milwaukee Blood Center, Inc., 23 Wis. 2d 324, 127 N.W.2d 50 (1964); Dibblee v. Dr. W. H. Groves Latter-Day Saints Hosp., 12 Utah 2d 241, 364 P.2d 1085 (1961); Gile v. Kennewick Pub. Hosp. Dist., 48 Wn. 2d 774, 296 P.2d 662 (1956); Perlmutter v. Beth David Hosp. Dist., 308 N.Y. 100, 123 N.E.2d 792 (1954). GONZAGA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 5:157 of blood. What about whiskey? It's really rather dreadful stuff; it causes all sorts of things from drunken driving to cirrhosis of the liver. It kills a lot of people, and its evils were once the subject of a political party which is still in existence and an amendment to the Constitution which is not. Is the manufacturer of good whiskey -and I mean good whiskey, and not whiskey which is full of old cigar stubs and things like that, or diesel oil or strychnine or arsenic-is the manufacturer of good whiskey to be liable for all the harm which it does? Well, there are Dram Shop Acts which make the retailer virtually liable when he sells to a person who is already intoxicated. But suppose that the seller does not sell to an intoxicated man; suppose he just sells a bottle of Haig & Haig over the counter, and the man comes down with chronic alcholism from drinking it. Is the seller going to be liable? What about sugar which is deadly poison to diabetics? What about butter which, according to the medical theory in vogue, deposits cholesterol in your arteries and brings on heart attacks? Is the seller of butter to be liable for the heart attacks, particularly if the plaintiff is very fond of butter and consumes excessive quantities of it over the years? What are you going to do with all kinds of drugs-many of them new and quite experimental, whose dangers and characteristics are only partially known or perhaps not known at all? Have in mind that, in terms of drugs, the two greatest benefactors to the human race, in my life-time, have been penicillin and cortisone. Both of those drugs involve serious dangers to some users. There is nothing that can be done; there is nothing known to science which can remove those dangers from those drugs at the present time. Are the suppliers of penicillin and cortisone to be liable for all the unpleasant and disagreeable things which may happen to those who use the drugs? Such cases as have come along have said that unless there is something in the way of negligence in the picture-failure to make appropriate tests; failure to make proper investigation of the drug before it is marketed; failure to give due warning as to the possible dangers-unless there is some negligence in failing to do that, then there is no strict liability for such products.2 2 You cannot impose strict liability upon a man who sells what appears to be a perfectly reputable product and is actually extremely beneficial to the human race; you cannot make him strictly liable because once in a while something goes wrong with it in a way which he cannot prevent. 22 See, e.g., Butler v. Travelers Ins. Co., 202 So. 2d 354 (La. App. 1967) (defendants not liable for tetanus contracted from penicillin injection). Spring, 1970] PRODUCTS LIABILITY That brings us, of course, to cigarettes and lung cancer. There were four cases on cigarettes and lung cancer and they went four 23 different directions. A Pennsylvania case-the Pritchard case placed strict liability on the manufacturer's cigarettes for lung cancer. Two cases, one in Louisiana24 and one in Missouri, 25 denied that there was any liability. The last one, in the fifth circuitGreen v. American Tobacco Company2 6 -went through an almost unique comedy of errors. The fifth circuit proceeded to refer the matter to the Florida Supreme Court under a curious procedure they have down there, and asked for a statement of Florida law. They asked all of the questions except the right one." The Supreme Court of Florida carefully answered these questions, and pointed out that it wasn't answering the right one because it had not been asked.2" The court then left everything to the jury which returned a verdict for the plaintiff. On various motions for a rehearing the case went back and forth, and finally the whole matter was sent down for a re-trial. The jury apparently disposed of the matter by returning a verdict for the defendant, whereupon, on one more appeal, the fifth circuit proceeded to reverse that and hold for the plaintiff as a matter of law.2 9 Then, on rehearing, it changed its mind and ordered final judgment for the defendant.3 0 So much for these questions; they are not settled. Are there products which are so bad and so dangerously unfit for use that anybody who puts them on the market, unaware of the inherent danger, is going to be strictly liable? Is there any sort of limit on the rule that as long as you can't do anything about the product you are free to market it? Is there such a thing as negligence, or even strict liability, for putting on the market something that ought not to be there at all? I can't answer such questions; I don't know. The second question I want to explore is: "What about the bystander?" The warranty theory and the strict liability in tort theory both originated as a matter of liability to the ultimate user 23 Pritchard v. Liggett & Myers Tobacco Co., 295 F.2d 292 (3d Cir. 1961). On a second trial the jury found for the defendant, and this was again reversed, for error in instructing on assumption of risk, when there was no evidence that the plaintiff was aware of the risk. Pritchard v. Liggett & Meyers Tobacco Co., 350 F.2d 479 (3d Cir. 1965). See Prosser, The Fall of the Citadel (Strict Liability to the Consumer), 50 MnN. L. Rav. 791, 812 n.111 (1966). 24 Lartigue v. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., 317 F.2d 19 (5th Cir. 1963). 25 Ross v. Philip Morris & Co., 328 F.2d 3 (8th Cir. 1964). 26 304 F.2d 70 (5th Cir. 1962). 27 The question put to the Florida Supreme Court was whether Florida law would imply a warranty when the defendant could not have know that the product was dangerous. The "right" question should have been: Is there a breach of warranty when a product in common use has inherent dangers which cannot be eliminated? 28 Green v. Am. Tobacco Co., 154 So. 2d 169 (Fla. 1963). 29 Green v. Am. Tobacco Co., 391 F.2d 97 (5th Cir. 1968). 30 Green v. Am. Tobacco Co., 409 F.2d 1166 (5th Cir. 1969). GONZAGA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 5:157 or consumer of the product. "User or consumer," in a very broad sense, means somebody who has something to do with the product in some manner resembling use. There was a case down in California where a man walking down the corridor walked into a practically invisible glass door and walked right through it and cut himself. The court called him a user of the door; you can see that he was-he was using it to walk through. There was a case in Illinois where a husband had bought rabbits for supper." His wife was cooking the rabbits for him, although she didn't like rabbit and wasn't going to eat them herself. While cooking them she contracted tularemia, and the court said she was a user of that product. A repairman working on the wheel of a car has been held to be a user. A passenger in an airplane 32 or an automobile 3 is a user. You don't have any trouble in finding liability without privity of contract to such people as these. But what about the man who is just standing on the sidewalk when the Buick wheel breaks and the car comes up and rams him in the rear? He never even sees it, yet wakes up in the hospital. What about him? Now, as far as negligence is concerned, there hasn't been any trouble since 1918. Any defendant who is negligent along the chain of sales is going to be liable to a plaintiff. But, do you have this strict liability to a person with whom the defendant has had no dealings and whom he cannot even contemplate as someone likely to use the product? On that, the cases have split. They began with a set of decisions saying that these rules of warranty were not intended to apply to anybody but a user or consumer. At one stage of the game there was a considerable majority in favor of the position that there was no strict liability to the bystander. Then the reaction in the other direction set in. The leading case, I think, was Piercefield v. Remington Arms Company,3 4 a Michigan case wherein the plaintiff was standing alongside a man who was shooting a Remington shotgun. The shotgun exploded and the plaintiff was injured. The Michigan court said there was an implied warranty running to him, even though he was not using the shotgun, wasn't interested in it, and had no concern with it. Piercefield was followed by various other decisions. 5 There Haut v. Kleene, 320 11. App. 273, 50 N.E.2d 855 (1943). See, e.g., Pub. Admin. v. Curtiss-Wright Corp., 224 F. Supp. 236 (S.D. N.Y. 1963); Ewing v. Lockheed Aircraft Corp., 202 F. Supp. 216 (D. Minn. 1962); King v. Douglas Aircraft Co., 159 So. 2d 108 (Fla. App. 1963); Goldberg v. Kollsman Instrument Corp., 12 N.Y.2d 432, 240 N.Y.S.2d 592, 191 N.E.2d 81 (1963). 33 See, e.g., Thompson v. Reedman, 199 F. Supp. 120 (E.D. Pa. 1961). 34 375 Mich. 85, 133 N.W.2d 129 (1965). 35 See, e.g., Elmore v. Am. Motors Corp., 70 A.C. 615, 75 Cal. Rptr. 652, 451 P.2d 84 (1969); Darryl v. Ford Motor Co., 440 S.W.2d 630 (Tex. 1969); McCormack 31 32 Spring, 1970] PRODUCTS LIABILITY was a very striking one down in California-Elmore v. American Motors Corp.36-this year, where American Motors made a car which Mrs. Elmore was driving. Suddenly, a large chunk of the bottom fell out and dragged along the highway. The driver lost control of the car, veered onto the left side of the highway and rammed head-on into Mrs. Waters. The suit was brought by Mrs. Waters who was 'in the position of what I call a bystander. The California Supreme Court, Justice Peters writing the opinion, proceeded to say that strict liability in tort as applied in California would allow Mrs. Waters to recover. She didn't have to be a user or consumer of the car which hit her. It was enough that she was in the path of the probable use of the car and was forseeably to be injured in case anything went wrong with it. In other words, a negligence theory was applied to the strict liability. The bystander cases are mushrooming all over and I would say that the split at the present is probably about fifty-fifty. 7 That's just an estimate; I haven't made any accurate count as to how the cases go. It's rather difficult determining what the rule ought to be. If your theory is that strict liability is imposed with the idea of making the enterprise bear the cost of all resulting harm inflicted upon anybody-making the enterprise insure against that and distribute the cost by means of insurance premiums to others engaged in the enterprise, and adding that cost to the price to the public in general-if that's your theory, then there is not the slighest reason to distinguish between injury to Mrs. Elmore, who was driving the car, and Mrs. Waters, who was hit by it. It became quite impossible to work out any kind of distinction. As Justice Peters said, Mrs. Waters is more entitled to protection because she is completely helpless, whereas Mrs. Elmore could have at least picked the kind of car she purchased. v. Hankscraft Co., 278 Minn. 322, 154 N.W.2d 488 (1967); Mitchell v. Miller, 26 Conn. Supp. 142, 214 A.2d 694 (1965). 36 70 A.C. 615, 75 Cal. Rptr. 652, 451 P.2d 84 (1969). 37 Cases allowing recovery by a bystander: Deveny v. Rheem Mfg. Co., 319 F.2d 124 (2d Cir. 1963); Brown v. Chapman, 304 F.2d 149 (9th Cir. 1962); Sills v. Massey-Ferguson, Inc., 296 F. Supp. 776 (N.D. Ind. 1969); Hacker v. Rector, 250 F. Supp. 300 (W.D. Mo. 1966); Montgomery v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 231 F. Supp. 447 (S.D. N.Y. 1964); Elmore v. Am. Motors Corp., 70 A.C. 615, 75 Cal. Rptr. 652, 451 P.2d 84 (1969); Lily-Tulip Cup Corp. v. Bernstein, 181 So. 2d 641 (Fla. 1966); Haley v. Merit Chevrolet, Inc., 214 N.E.2d 347 (Ill. App. 1966); Wagner v. Larson, 136 N.W.2d 312 (Iowa 1965); Piercefield v. Remington Arms Co., 375 Mich. 85, 133 N.W.2d 129 (1964); Connolly v. Hagi, 24 Conn. Supp. 198, 188 A.2d 884 (1963); Jakubowski v. Minn. Mining & Mfg. Co., 80 N.J. Super. 184, 193 A.2d 275 (1963). Cases denying liability: Mull v. Colt, 31 F.R.D. 154 (S.D. N.Y. 1962); Kuschy v. Norris, 25 Conn. Supp. 383, 206 A.2d 275 (1964); Hahn v. Ford Motor Co., 126 N.W.2d 350 (Iowa 1963); Rodriguez v. Shell's City, Inc., 141 So. 2d 590 (Fla. App. 1962). GONZAGA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 5:157 On the other hand, if your theory is that the defendant, in selling this product, has somehow represented to possible purchasers of the product and to users and consumers, that it is fit for useif he has invited their purchase or use or consumption in reliance upon that representation, and if they have bought in reliance upon that representation-then it is very hard, indeed, to justify a recovery by the bystander. He has relied upon nothing. He is not the kind of person who the defendant has been seeking to reach; no representation has been made to him expressly or impliedly. He has done nothing except to be there when the accident happened. Did you ever know any plaintiff who wasn't there when the accident happened? In other words, all this man is is a plaintiff, and that's his only qualification on this theory. The courts are going to be compelled to make up their minds as to what they are trying to do. Are they adopting a so-called socialistic theory, a compulsory insurance, risk distribution and so on? Or are they going to adopt the theory that this thing is justified by the defendant's conduct in putting the product on the market, and representing to the public that it is fit for use? On the cases so far there has been about an even split. This is another problem that we are going to have to work out and settle, and you will probably hear a good deal of it during your lifetime. I may not live long enough to see it settled, but some of you at least will. The third problem I want to talk about is: "What is to be done about pecuniary loss?" Suppose that the plaintiff buys an automobile-and in order not to be invidious and start naming manufacturers, let us say he buys a Mercedes-and it turns out that the car is a lemon. Our man pays, let us say, $5,000 for that car, and it has so many defects that it is worth not more than $2,000. Can he recover, without proof of any negligence on the part of anybody, that loss of $3,000--the pecuniary loss-the loss of the bargain? If so, from whom? This has gone both ways in a lot of cases. Where there is an express warranty in the picture the cases are pretty generally agreed that the plaintiff can recover for pecuniary loss from anyone who has made him that express warranty. But where there is no express warranty, and he is suing on implied warranty, or better still, where he is suing on this theory of strict liability in tort, then he has his difficulties. About half of the cases have held that he can recover for the pecuniary loss. About half of them have held that he cannot. Perhaps the leading case holding he cannot is Seely v. White Motor Co.,38 a California case in which Justice Traynor 38 63 Cal. 2d 9, 403 P.2d 145 (1965). Spring, 1970] PRODUCTS LIABILITY returned to the fray once more, and denied recovery when a truck turned out to be defective and wouldn't do the job. Now if you stop to analyze this and you think about loss of the bargain, which is what you are suing for, you will have a problem. The plaintiff's pecuniary loss of the bargain depends upon what the bargain is. What price did he pay? I gave the illustration of paying $5,000 for the Mercedes and getting a car worth only $2,000. Now on its face that is deceptively simple. It has proved so deceptively simple that it has taken in some of our courts. Suppose, on the other hand, that our purchaser is overcharged by the dealer and pays $7,000 for that car. He has, of course, a $5,000 loss now, instead of a $3,000 loss. But how much of that $5,000 is to be attributed to the manufacturer who put a defective car onto the market in the first place? How much of it is to be attributed to the dealer who overcharged the plaintiff when he sold him the car? When you realize that on most automobile sales now there is a trade-in of an old car and a dealer's allowance made, the problem of the fair allowance and the marked-up price gets into the picture. You realize that this becomes a rather difficult problem to work out. Furthermore, if there is nothing wrong with the car at all, and the plaintiff is overcharged, he has suffered an economic loss. Of course he can't pass that back to the manufacturer, because there was nothing to charge the manufacturer with. The difficulties here appear to be so great that I would guess the ultimate answer is that this problem of pecuniary loss is something that ought to be worked out between the plaintiff and the retail dealer from whom he purchases the car in the first instance. In other words, he should sue the dealer and establish his loss, and then the dealer would pass on whatever portion of it he is justified in passing on to the manufacturer. It ought to be a two-stage operation, rather than an attempt to struggle with the problems of proof you have in one stage. However, I have to say that the cases are so badly split, I can see no definite trend in that direction. Editor's note: At this point the meeting was opened to questions from the floor. Dean Prosser'sresponses to two such questions follow. Question: Where a physician administers a drug to an infant, making a separate charge for the drug, and the drug causes harm to the child, what is your opinion as to the liability of the physician and the applicability of the strict liability theory? Dean Prosser: There have been some few decisions on the subject and they have quite unanimously held that in the absence of negligence, the physician is not going to be held liable. Now, of course, he can be negligent if he picks the wrong drug or if he GONZAGA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 5:157 negligently administers it and so forth. That is not what we are talking about-we are talking about strict liability. All of the cases I know of-and I think that there are about a half a dozen altogether-have held that there is no strict liability under those conditions. The usual backdoor through which the court escapes is to say that this is not a sale, that even though a drug is billed by the physician as part of his professional services, nevertheless he is not in the business of selling that kind of a drug, nor has he technically sold it. What he has done is to administer it as part of his professional services. It is a service and not a sale. While I think in many cases that it has been an escape through the backdoor, I would regard it as pretty well justified in this type of situation. I do not think that the doctor should be held in the absence of some kind of negligence. I do not see why strict liability should apply to him. One of our young men wrote a piece in the Hastings Law Journal 9 not so long ago, recommending the doctor be held strictly liable so that the cost could be passed on through him to the manufacturer. I do not agree with this approach; but there it is in the Hastings Law Journal embalmed for posterity, assuming there is going to be any. Question: Dean Prosser, in considering the defense of abnormal use to strict liability, do you think the courts should focus on the reasonable, foreseeable use or upon the use that the manufacturer intended? Dean Prosser: Well, I would have to make a distinction or two. The manufacturer is entitled to expect a normal use of his product by a normal user, in the absence of some reason to look for something to the contrary. Of course, normal uses may include a lot of things that are relatively unexpected. A woman stands on a chair to reach a high shelf-this has been held to be a normal 40 use. The question of what is normal becomes, I think, a question of what the product is being supplied for, and what relatively unusual things you can expect. It certainly is not limited to what the manufacturer intends the product to be used for. Take the case here in Washington, Ringstad v. I. Magnin & Co.,4 where a woman 39 Comment, 17 HASTINGs L.J. 359 (1965). 40 Phillips v. Ogle Aluminum Furniture, Inc., 106 Cal. App. 2d 650, 235 P.2d 857 (1951). Other situations in which courts have found no "abnormal" use are: Brown v. Chapman, 304 F.2d 149 (9th Cir. 1962) (dancing in hula skirt); Ringstad v. I. Magnin & Co., 39 Wn. 2d 923, 239 P.2d 848 (1952) (wearing cocktail robe in kitchen near stove); Maddox Coffee Co. v. Collins, 46 Ga. App. 220, 167 S.E. 306 (1932) (eating coffee). 41 39 Wn. 2d 923, 239 P.2d 848 (1952). Spring, 1970] PRODUCTS LIABILITY bought a cocktail robe and wore it in the kitchen in proximity to a gas stove. As she leaned over the stove, the robe, being highly inflammable, caught fire and she was injured. I. Magnin attempted to defend by saying that cocktail robes were not expected to be worn in the kitchen, that they were not intended for that. Well, of course, they got nowhere with that. A woman will wear whatever she is wearing when she goes out and sees how things are cooking on the stove. It was to be expected that the robe would come in contact with that kind of fire. There was a case in Illinois, Hardman v. Helene Curtis Indus., Inc.,42 which involved another inflammable product. There was some kind of cosmetic which got into the hands of a child who proceeded to daub himself up with it. The product was highly combustible and the child was seriously burned when he came into contact with a fire. The manufacturer was held liable for providing something which could get into the hands of children. There was no warning on the bottle indicating that if it did get into the hands of children, it would be dangerous to them in case they came in contact with fire. It would be ridiculous to say that he intended that resulthe never intended it to be used by a child daubing himself up with it-but there was certainly a foreseeable risk. At the same time, the manufacturer is entitled, I think, to put warnings and directions upon his products, and assume, in the absence of some reason to think to the contrary, that these warnings and directions will be followed. There was Fredendall v. Abraham & Strauss, Inc.,43 where the defendant sold a bottle of carbon tetrachloride-Carbona, or some such product like cleaning fluid. He put warnings all over the bottle and the literature which accompanied it: "Don't use this stuff in a small closed room." The plaintiff, having read the warnings proceeded to use the product in a small, closed bathroom. As it happened, the plaintiff had had a few drinks before hand; and in case you do not know, carbon tetrachloride and alcohol make about the most dangerous possible combination you can get. The plaintiff was very nearly killed by all this, and the manufacturer was held not liable. What more could he do? Carbon tetrachloride is a reasonably safe cleaning fluid, assuming it is properly used. He had given the warning. At this point you can say that in the light of the warning, what he intended the product to be used for is going to be controlling. Do you get the distinction? Maybe I haven't made it very clear. He is under a duty to warn 42 48 I1. App. 2d 42, 198 N.E.2d 681 (1964). 43 279 N.Y. 146, 18 N.E.2d (1938). 174 GONZAGA LAW REVIEW against foreseeable things. He is under a duty to warn the woman not to go near an open flame with the robe on; or not to use cleaning fluid in small, closed areas. Once he has given the warning, he can assume that that warning has been followed. Here, I think, the question of what is intended becomes important." 44 After beginning his answer by stating that "the manufacturer is entitled to expect a normal use of his product by a normal user," Dean Prosser seems to come to the conclusion that wherever there is a "foreseeable risk," the manufacturer has at least the duty to warn, if not the absolute duty to make safe the product. For example, tires that were intended by the manufacturer to be properly mounted should, nevertheless, have been accompanied with warnings of any dangerious propensities. See Barth v. B.F. Goodrich Tire Co., 265 A.C. 253, 71 Cal. Rptr. 306 (1968) Cassetta v. U.S. Rubber Co., 260 Cal. App. 2d 792, 67 Cal. Rptr. 645 (1968).