HROB/092

ICMR Center for Management Research

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’:

Changing the Productivity Paradigm?

This case was written by Shirisha Regani, ICMR Center for Management Research. It was compiled from published sources,

and is intended to be used as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a

management situation.

Aruna Manharlal Saha Inst. Of Management & Research,

Mumbai

License to print 10 copies.

2007, ICMR. All rights reserved.

To order copies, call 0091-40-2343-0462/63 or write to ICMR, Plot # 49, Nagarjuna Hills, Hyderabad 500 082, India or email

info@icmrindia.org.

www.icmrindia.org

Best Buy‟s „Results Only Work Environment‟:

Changing the Productivity Paradigm?

"ROWE was an idea born and nurtured by a handful of passionate employees. It wasn't created as

the result of some edict."

– Brad Anderson, CEO and Vice Chairman of Best Buy, in 2006. 1

“Our whole notion of paid work was developed within an assembly line culture. Showing up was

work. Best Buy is recognizing that sitting in a chair is no longer working."

– Phyllis Moen, a Professor of Sociology at the University of Minnesota, in 2006.2

“You can ridicule an obsession with face time, for example, but some companies have a strong

belief that having people at the same place, in the same time, creates synergy that is valuable to

the company. You’re going to have a hard time changing that.”

3

– Paul Rupert, a flexibility consultant at Washington DC-based Rupert & Co., in 2006.

A NEW KIND OF WORKPLACE

In 2005-2006, Best Buy Co., Inc. (Best Buy), one of the leading retailers of consumer electronic

products in the US, was in the news for implementing an innovative workplace program called

„Results Only Work Environment‟ or ROWE, for its corporate employees4. ROWE, as the name

indicated, focused only on „results‟ as a measure of employee productivity. Under ROWE,

employees were allowed to work when they wanted, where they wanted, just as long as they

achieved their targets. Hours were not measured and putting in an appearance at the office was not

necessary.

As of late 2006, the program was still finding its feet, but it was already widely discussed and

analyzed. In some corporate circles, ROWE was hailed as a path-breaking program, which would

give new meaning to flexibility and work/life balance. Skeptics however, were concerned about

the chaos that could be created if thousands of employees in every organization worked without

authorized boundaries.

ROWE differed from traditional „flexible work schedules‟ in that, under flexibility, employees

were still expected to put in an appearance at the workplace. Either the start and finish times were

flexible, or employees worked for a certain number of days in the week at home and the rest at

office. Under ROWE however, coming in to office was entirely voluntary. Even physical

attendance at meetings was not compulsory.

1

2

3

4

George Anderson, “Best Buy Realigns Work Environment for Results,” www.retailwire.com, December 7, 2006.

Michelle Conlin, “Smashing the Clock,” BusinessWeek, December 11, 2006.

Patrick J. Kiger “ROWE‟s Adaptability Questioned,” Workforce Management (accessed on December 26, 2006.)

It did not apply to retail employees as of early 2007.

1

Aruna Manharlal Saha Inst. Of Management & Research,

Mumbai

License to print 10 copies.

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

In the early 2000s, workplace stress had become a matter of concern in the US as well as other

developed economies in the world. In the US, the number of hours in the work-week had

reportedly increased from the earlier-typical 40 hours, to more than 60 hours (stretching to even 80

hours in some industries). Moreover, it was said that Americans worked longer hours than any

other workforce in the world.5 In this scenario, many reputed companies set up work/life balance

programs, which allowed employees to prioritize their activities. ROWE was the most radical of

these programs.

BACKGROUND

Best Buy‟s history starts in 1966, when Richard Schultz (Schultz), and his partner opened an audio

specialty store called „Sound of Music‟ in St. Paul, Minnesota. Business grew, and the partners

opened two new stores near the University of Minnesota in 1967.

In 1969, Sound of Music stock began to be traded publicly, and the company also established its

first employee stock option plan. The next year, the company breached the one million dollar 6

sales mark for the first time. Over the next decade, Sound of Music grew rapidly, and improved its

offerings by including the latest video and laser disc equipment in its product lineup (it was also

the first retailer in the US to sell video equipment).

In 1983, Sound of Music‟s board of directors approved a proposal to change the company‟s name

to Best Buy. The company‟s first superstore under the „Best Buy‟ name opened in Burnsville in

Minnesota. The superstore was much larger than most electronics stores and featured an expanded

product and service range including a wide assortment of discounted brand-name goods, central

service, and warehouse distribution. The store also started selling consumer appliances.

Best Buy was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1987. In the late 1980s, the company

adopted the unique „yellow tag‟ design for its logo (Refer to Exhibit I for the logo). In 1989, Best

Buy implemented a new policy where it stopped paying commissions to its sales staff, shifting

them instead to a salary. This did not go down well with both the sales staff as well as electronics

and appliance companies like Toshiba Corporation and Hitachi Ltd., which depended on sales staff

to push their premium-priced products. However, customers reportedly liked the „no-pressure‟

atmosphere at the stores which resulted from the sales staff being less pushy.

Revenues grew rapidly after this, and Best Buy embarked upon an expansion spree. In the early

1990s, it entered markets like Chicago, Philadelphia, and Boston. In 1995, Best Buy became the

biggest seller of personal computers (PCs) in the US, which placed it in a good position to take

advantage of the internet boom of the late 1990s. In 1996, Best Buy became the largest electronics

retailer in the US, overtaking Circuit City Stores Inc7.

In early 2001, Best Buy acquired Musicland Stores Corp. (Musicland), a mall-based retailer of

CDs, for $685 million8. Although Best Buy had hoped to expand its presence in the music industry

through the acquisition, the move backfired, as sales of CDs were adversely affected by the

increasing popularity of MP3s during that time. In the same year, Best Buy launched Redline

Entertainment, an independent music label and action-sports video distributor.

5

6

8

Lesley Stahl, “Working 24/7,” CBS News, July 23, 2006.

Dollars ($) refers to US dollars.

7

Circuit City was a Richmond, Virginia based electronics retailer. As of 2006, Circuit City was the third largest

electronics retailer in the US behind Best Buy and Wal-Mart Stores Inc.

“Best Buy sells Musicland unit,” New Mexico Business Weekly, June 16, 2003

2

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

In 2002, Brad Anderson (Anderson), who had joined Best Buy in 1973, succeeded Schultz as the

CEO. Best Buy‟s business was badly affected in the early 2000s by the economic slowdown that

followed the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. In addition to this, discounters like Wal-Mart

Stores Inc. (Wal-Mart) and Costco Wholesale Corporation (Costco) had started expanding the

range of their consumer electronics offerings, which resulted in increased competition for Best

Buy.

In October 2002, Best Buy acquired Geek Squad, a Minneapolis-based startup that specialized in

repairing and installing PCs. The market for digital devices and home networks was booming in

the early 2000s, and the technical services market had huge potential. Besides, it was thought that

providing installation and services would help differentiate Best Buy from companies like WalMart, which typically did not provide such services. (Over the next few years, Geek Squads were

set up at all Best Buy stores and became one of the most successful businesses for the company.)

By the early 2000s, Best Buy had opened stores in all the major markets of the US. The company

then started looking at international markets, opening its first store outside the US in Toronto,

Canada, in late 2002. In 2003, the company had 600 stores across the US. That same year, it

opened its first global sourcing office in Shanghai, China. It also moved to a new corporate

headquarters in Richfield, Minneapolis.

In the early 2000s, Best Buy‟s growth in the US had begun to plateau. In a bid to provide an

impetus to growth, Andrerson launched a new „centricity‟ initiative at the company in 2003. Under

this initiative, each of Best Buy‟s stores was to be redesigned to appeal to a specific pre-defined

customer segment like „affulent tech enthusiast‟, „suburban homemaker‟, „young gadget fiend‟,

and „price conscious family guy‟. (Some stores catered to two or more segments). In the same

year, Best Buy divested its stake in Musicland.

In 2004, Best Buy launched „Learning Place‟, a post-purchase, online customer service center,

which allowed customers to purchase secure access to interactive product user-manuals, live

text/voice chat services and a discussion forum to help them use, fix and extend the products they

had bought. In 2006, Best Buy acquired a majority interest in China‟s fourth-largest appliance and

consumer electronics retailer Jiangsu Five Star Appliance Co. Ltd. The company also announced

that it planned to open stores in Shanghai in the future.

As of late 2006, Best Buy operated over 740 Best Buy stores, 20 Magnolia Audio Video Stores,

and 12 stand-alone Geek Squads in the US. Additionally, the company operated 44 Best Buy

stores, 118 Future Shop stores, and five stand-alone Geek Squad operations in Canada. In the fiscal

year ended February 2006, Best Buy posted revenues of $30.8 billion, and a net income of $1.1

billion (Refer to Exhibit II for Best Buy’s Annual Income Statement). The company employed

around 128,000 people in 2006.

BEST BUY‟S WORK CULTURE

Over the years, Best Buy had evolved a demanding work culture that glorified long hours.

Rewards and recognition went to employees who were willing to give work priority over personal

life, and there was little scope for work/life balance. Reportedly, a Best Buy manager once gave a

recognition plaque to an employee “who turns on the lights in the morning and turns them off at

night.”9

Managers monitored their teams closely, and flexibility was unheard of. For example, one manager

reportedly asked his team to sign-out before going out for lunch, giving their destination and

contact information.10

9

10

Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

Michelle Conlin, “Smashing the Clock,” BusinessWeek, December 11, 2006.

3

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

It was also common for employees to stay back late at the office for days on end to complete

important projects. Darrell Owens (Owens), a Best Buy employee for 14 years, said that he once

stayed up for three days in a row to write a report that was due all of a sudden. The company gave

him a bonus and a vacation for his efforts, but he had to be admitted to hospital first.11 Employees

said they sometimes had to cancel planned vacations because of work pressure.

Best Buy justified its demanding work culture on the grounds that it operated in an industry where

margins were low and competition was high. The company had to constantly find ways to do

things faster and better than competitors, while keeping costs at a minimum. This however, was

causing employee burnout.

Things had become so serious that many employees at Best Buy‟s headquarters had started

quitting, citing high work stress as the reason. There was also an increase in the number of people

filing stress-related health claims. It was also observed that there was an increasing number of

women employees who were accepting lower pay and status just to obtain the flexibility they

needed, despite their work experience and capabilities.

THE “RESULTS ONLY” WORK ENVIRONMENT

In 2003, Cali Ressler (Ressler) and her colleague at Best Buy‟s HR department, Jody Thompson

(Thompson), got together unofficially to try and develop a new workplace program that would

stem the constantly increasing attrition at the company. They came up with the program that later

came to be known as ROWE. However, they realized that the program was too radical for it to get

approval from the top management. Therefore, they waited until the right opportunity came up to

implement it. Eventually, the program was launched clandestinely at two corporate departments

(the properties and communications divisions) where the attrition was exceptionally high.

Ressler and Thompson managed to convince the managers of these two departments (who by then

were reportedly desperate enough to do anything to control the attrition) to try a workplace

program where employees were evaluated on the results achieved and nothing else. They called

this program ROWE.

The main objective of ROWE was to lower stress and improve employee morale. Ressler and

Thompson reasoned that stress could come down if employees were allowed to achieve their

targets at their own convenience, without having to account for their hours. They felt that „work‟

need not mean being in a certain place at a certain time for a specific number of hours. They

thought productivity could improve if employees were allowed to work when and where they

wanted instead of being tied to their desks at office.

The managers of the departments where the pilot program was conducted were encouraged to try

flexible scheduling, trusting their team members to work as it suited them. „Trust‟ was the

operative word in ROWE. The managers of these departments reportedly went along with the

program because it „did not cost them anything to trust their teams‟.

The initial results for ROWE were encouraging. In the first three months, turnover in these

departments fell from 14 percent to zero, job satisfaction increased 10 percent and productivity

improved 13 percent. The results encouraged Ressler and Thompson to try extending the program

to the other departments at the headquarters.

By this time, people in other departments had started hearing about ROWE and were curious about

it. Most of the lower level employees were excited about a „no restrictions‟ work environment. But

many managers were reportedly extremely skeptical about how it would work. Therefore, the

implementation of ROWE at Best Buy‟s headquarters was a slow process.

11

Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

4

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

The unique thing about ROWE was that it was a grassroots program. The top management had no

idea that such a program was being initiated at the company at the time it was launched, and many

of them, including Anderson, reportedly found out about it more than a year after it was launched.

THE WORKING OF ROWE

ROWE was a system which worked on the principle that productivity was the cornerstone of work.

Working did not mean being at office. Rather, work was done when results were accomplished.

ROWE‟s vision was that productivity at work should be measured by output and not by the

number of hours spent on the work.

Employees were assigned targets of what to achieve in a certain time frame (targets could be

weekly, monthly or quarterly, depending on the nature of their work and the level in the

hierarchy). Targets were usually set jointly by the manager and the employee. The employee was

then responsible for achieving these targets. Employees could choose to pace work in a way that

was convenient to them. They could also work at whatever time of the day was convenient for

them and from wherever they wanted.

ROWE created an inclusive system, which recognized that different people had different needs.

For instance, different people were productive at different times of the day. By making all people

work during set hours, the company could be losing out on their productive best. Since ROWE

allowed people to work at whatever time they felt like working, it ensured that they put in

optimum performance. Marissa Plume, a Best Buy employee, worked better at night and said she

did her best work from her bedroom at midnight after shifting to ROWE.12

Whenever a department signed up for ROWE, the entire department did so together, so that no

employee felt left out. Teams joining up for ROWE had to first work out a system by which they

could get in touch with each other when needed. Initially some teams set up an online calendar in

which everyone entered exactly where they were at any given time. Others hung whiteboards

outside their cubicles with messages like „in office today‟ or „Out of the office this afternoon,

available by e-mail.‟13 Every department had its own rules and measures to prevent flexibility from

generating chaos. For instance, the public relations department employees used pagers to ensure

that someone was always available in an emergency. Other employees made extensive use of their

cell phones and laptops to get work done even though they were not in the office.

Teams were also required to prioritize their tasks to ensure that important tasks were not ignored.

Most teams found that their regular meetings were redundant, and that they could get by with

meetings at less frequent intervals. Teams that adopted ROWE did away completely with

impromptu meetings. If meetings were necessary, they used technology like conference calling or

dialed into the meeting from wherever they were.

Traci Tobias (Tobias), the manager of the travel reimbursements team at Best Buy admitted that

the number of meetings her team held had fallen drastically after they shifted to ROWE. Earlier

the team used to lose a lot of time in unnecessary meetings, which usually ended up in idle talk.

But after the implementation of ROWE, people simply contacted the person they needed to speak

to through e-mail or cell phone, without having to set up a formal meeting and involving several

other people in it. Tobias confirmed that conversations among team members had become more

concise and to-the-point as the number of meetings decreased.

Teams also worked out the division of the tasks among themselves. For instance, if a client needed

someone to be present in office on a particular day, the managers did not take the decision as to

who should be available, but left the decision to the team members. Managers said that after the

12

13

Lesley Stahl, “Working 24/7,” CBS News, July 23, 2006.

Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

5

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

implementation of ROWE they had to start planning their teams‟ tasks more carefully, as they

needed to give them clear indications of what was expected from them. They could no longer just

stop by their employees‟ desks and allot work as they were not likely to be there.

ROWE teams had no typical working day. They came and went when they wanted. Reportedly,

some employees did not come to the office for weeks at a time after they shifted to ROWE, but

their productivity did not drop.

NOT AN EASY ROAD

Implementing ROWE was not easy. In the first place, it required a complete overhaul of people‟s

attitudes towards work. Traditionally, employees were programmed to think that displaying a

commitment to work by coming in early and leaving late could ensure them success. But this was

eliminated as a criterion for judging performance under ROWE.

Several employees who were working with ROWE admitted to having misgivings about whether

they would be able to cope with the new system. Some people reportedly felt confused about what

would be expected from them at the workplace. Staying longest at the office was no longer a

guarantee of success. Denise LaMere, a Best Buy corporate strategist, was one of the employees

who found it difficult to adapt to the new environment. LaMere did not have children, and

therefore had had an advantage earlier as she could spend long hours at the office. Under ROWE

however, long hours at the office became pointless. “It made me very nervous. I had all this panic.

Everything we knew about success was suddenly changing,” she said.14

Employees could also no longer look to the top for directions and instructions, which made them

feel vulnerable. “It takes away everything that you felt was normal,” said Owens.15 In the early

stages of the program, employees reportedly felt guilty when they took time off for their families

or to pursue their hobbies, and it took them a lot of time to adapt to the new way of doing things.

Managers, on the other hand, had to be able to give up control and trust their employees to get

their work done. Many managers wondered how they would establish authority if they could no

longer control their employees‟ work time. When ROWE was launched, some managers resisted it

strongly as they felt that their authority would be undermined. Many managers felt that it was big

mistake to allow employees to work as and when they wanted. They argued that this might work

well in the case of employees who were self motivated, but when applied indiscriminately to all, it

would only lead to chaos and a drop in productivity.

Some managers also argued that in some jobs, face time between the managers and employees was

very important. For instance, many managers felt that administrative assistants need to be at their

desk to „serve‟ their bosses.16 (As of late 2006, this issue had still not been resolved.)

Another problem with ROWE was that, as of 2006, it was still restricted to a few departments at

Best Buy‟s corporate offices. Because of this, when employees were transferred from a department

which had ROWE to one that did not, they felt demoralized. On the other hand, employees who

were accustomed to regular hours of work felt disturbed when they moved to a ROWE department.

Best Buy also had to confront some barriers to change in implementing ROWE. Because

employees were accustomed to certain behaviors in the workplace, and had specific ideas about

what constituted productivity, it was not easy to bring about a change in their attitudes. People who

had flexible schedules or took time off were often criticized by their more „hardworking‟

colleagues.

14

15

16

Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

6

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

Ressler and Thompson used the term „sludge‟ to refer to the collection of attitudes and comments

at the workplace that hindered the progress of ROWE. Examples of sludge included comments like

“Wow, I wish I could come in at 10,” “Out late last night?” “Were you here this weekend?” etc.17

Such comments were meant to make people on flexible schedules feel guilty. Ressler and

Thompson understood that sludge was one of the biggest impediments to the acceptance of

ROWE. Sludge made it hard for people to take time off without feeling guilty and defensive.

Therefore, handling sludge was one the biggest tasks in a ROWE implementation. Departments

usually developed their own methods to combat sludge. For instance, some employees called

„sludge‟ out aloud whenever someone made a negative comment. Others put in a dollar in a kitty

for every sludge comment they heard. As a part of ROWE training, employees were given

suggestions on how to handle sludge without becoming defensive. For instance, when asked about

where they were or why they were not in office at a certain time, employees were taught to

respond with statements like “Was there something you needed?” and “Don‟t you have my cell?”

The expectation was that a positive and non-defensive attitude would one day eliminate sludge

from the workplace.

Some departments also resisted ROWE on the grounds that their work did not lend itself to

flexibility. The legal department at Best Buy was one of the departments that had chosen not to

adopt ROWE. The reason was that Best Buy‟s lawyers were compensated in part for how well

they served their clients, and they were worried that if they took an afternoon off, or were not in

the office when clients called, they might be labeled as unresponsive. It was also difficult to apply

ROWE for general administrative staff and retail employees.

THE OUTCOMES

As of late 2006, more than 50 percent of the employees at Best Buy‟s headquarters were on

ROWE. The company announced that ROWE had yielded positive results in the few years that it

had been in practice at the headquarters. Reportedly, ROWE teams had an average 3.2 percent

lower voluntary turnover than non-ROWE teams. Average productivity of ROWE teams had also

increased 35 percent.18 Employee engagement, which was a measure of job satisfaction and hence

an important factor in retention, was also reported to be significantly higher in ROWE teams.

Best Buy reportedly witnessed several non-quantifiable benefits as well. For instance, managers at

the company said that ROWE made their work easier. They admitted that, despite their previous

misgivings, performance was actually easier to track under ROWE than under conventional

systems. Similarly, problems were also easier to identify and correct. “You can find a performance

problem a lot faster on this program, because that‟s all you‟re looking for…,” said Chap Achen , a

departmental manager at Best Buy.19

Employees were happy with their freedom. Their stress levels were reported to have fallen

significantly as they no longer had to be answerable for their time. They also did not have to worry

when a personal emergency came up. They could simply work from wherever they were, if they

were not in a position to get to the office.

ROWE was especially appreciated by people who had families, as it gave them more time to spend

with them without feeling guilty. The work/life balance that they achieved because of ROWE far

exceeded what they could have hoped to achieve from regular flexibility programs. According to

Best Buy, ROWE was appreciated by both men and women for the work/life balance it provided.

17

18

19

Michelle Conlin, “How to Kill Meetings,” BusinessWeek Online Extra, December 11, 2006.

“Case Study,” http://culturerx.com (accessed on January 8, 2006)

“Working When and Where You Want,” www.abcnews.com, October 3 2005.

7

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

Tobias said that previously she used to avoid her two children, aged four and two, every morning,

because if they saw her they would ask her to stay for breakfast. But under ROWE, she no longer

had to do that, as she was free to schedule her time according to her needs. Her goals were clear

and she knew exactly what she had to complete by what time. This allowed her to make time for

her family, she said.20However, Tobias emphasized that working under ROWE did not mean that

she was giving more importance to her family than to her work. It just allowed her to balance both

aspects of her life better. “The family doesn‟t always win. But the family doesn‟t always lose

either. I don‟t feel guilty anymore,” she said.21

Ressler and Thompson said that older employees often admitted to them that they felt sad about

not being able to balance their work and lives better when they were younger. “People in the babyboom generation realize what they gave up to get ahead in the workplace, and a lot of times it‟s

their families. They realize that it doesn‟t have to be that way,” said Ressler.22 Joe Pagano, a Vice

President of merchandising at Best Buy said, “I basically worked every Saturday, and some

Sundays. It‟s one of the biggest regrets of my life.”23

For the company, one of the biggest benefits in addition to the increased productivity was the

program‟s value as a retention tool. It also helped Best Buy attract the best talent in its recruitment

programs. Starting 2007, the company was planning to use ROWE as a major selling point in its

campus recruitment program.

Third party vendors of Best Buy were also said to be happy because when they dealt with the

company‟s employees they were fully committed to the task on hand, as they did not have to worry

about the time, or need to get anywhere else in a hurry.

Best Buy was impressed with the early results from ROWE, and was so convinced about its

potential that it set up a wholly owned subsidiary called CultureRx in November 2006, to provide

ROWE-oriented consulting services to external clients. CultureRx was located at Best Buy‟s

headquarters in Minneapolis, and was managed by Ressler and Thomson. As of late 2006,

CultureRx still did not have any outside clients, but the company‟s public relations representative

Rebecca Selby said that they were in talks with some „very interesting‟ potential clients.24

ROWE‟S LIMITATIONS

Notwithstanding its acceptance among employees, ROWE had several kinks that needed to be

ironed out before the program could become a workplace standard. One of the biggest concerns

about ROWE was that the difference between the work and personal time of the employees could

become blurred. Some people felt that just because employees were not working when they should

be, they might be working at all times of the day, blurring the difference between work and leisure.

This had the potential to create more stress for them than long work hours, said some analysts.

After the adoption of ROWE, some employees were reportedly working longer hours than they did

before. Some employees admitted that they sometimes worked around 70 hours a week to

complete their tasks (The standard work week at Best Buy was 40 hours). However, they said that

they did not find it pressuring to work more hours because they spread their work over seven days

instead of five. They also admitted that although they worked more hours with no additional

monetary benefit, they were happy to do it because of the flexibility.25

20

21

22

23

24

25

Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

Patrick J. Kiger “ROWE‟s Adaptability Questioned,” Workforce Management (accessed on December 26, 2006.)

Lesley Stahl, “Working 24/7,” CBS News, July 23, 2006.

8

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

On the other hand, there was also a chance that managers might start piling too much work on

employees without any raise in compensation, if they saw that employees were regularly finishing

their work faster than expected and taking more free time. The general belief would be that

employees had been under-worked to start with, for them to be able to finish their work faster than

usual under ROWE.

ROWE was also highly reliant on metrics and the quantifiability of the work. This limited its

application to only those jobs where performance could be measured in quantitative terms.

However, not all the jobs in an organization lend themselves to quantification, which would make

it difficult to bring them under ROWE. ROWE would also not work for employees who preferred

to have clear schedules, and expected direction from their managers at all times.

Analysts also said that no matter what the benefits of ROWE, the program could not provide the

synergy created by face to face communication. Besides, some situations could be handled more

easily when the people were physically present. Some problems would only become more

complicated if they had to be handled over the telephone or by email. Some analysts also said that

ROWE was in fact not as innovative as Best Buy claimed. Technology companies had been

providing a similar environment to their employees for a long time. ROWE however marked the

first time when such a program had been taken up systematically in a company.

OUTLOOK

In late 2006, Best Buy announced that it was working on a project that would allow ROWE to be

implemented in a modified form in the company‟s retail stores, which employed almost 120,000

people. The company believed that an employee-friendly work environment could provide a

solution to the problem of high attrition in the stores. (Best Buy‟s voluntary attrition in its retail

stores was around 65 percent in 2006.)26 “It‟s a well-known fact that it‟s difficult to keep people

working in retail - not just at Best Buy - because of the hours and the stress. We want to look at

deeply held beliefs in the retail environment and whether they're actually in the way of both

associates‟ and customers‟ needs,” said Thompson.

Industry experts were doubtful about the efficacy of ROWE in a retail set-up. In a retail set-up

people were required to be in a certain place at a certain time. This went against the basic premise

of ROWE. Besides, most of the employees were hourly workers, and their employment was

governed by laws, which limited the flexibility to try new practices.

Best Buy, however, maintained that a modified version of ROWE could be implemented in its

retail stores. The management felt that the environment in the stores was very stressful for

employees, which was one of the reasons for the high turnover. Besides, they felt that an

unjustified amount of importance was given to timings, which added to the stress. “If you get

written up for being five minutes late for your shift, maybe that results in you being upset about it

for the next several hours and not giving as good of service to customers as a result,” said

Thompson.27

The company sought to eliminate this by setting up an employee-friendly scheduling system and

designing rewards and consequences around it. “We need to trust that when we give our retail

employees a scenario – store opens at this time, store closes at this time – we need to trust that they

will do what‟s right,” said Thompson.28 The new program would first be implemented in a pilot

store to chart its effect on productivity, employee and customer satisfaction, and turnover, and then

be extended to the other stores. The pilot project was expected to be rolled out in late 2007.

26

27

28

Lynne LaMaster, “Unplugging the Time Clock at Best Buy,” That‟s Crispy, December 11, 2006.

Patrick J. Kiger “ROWE‟s Adaptability Questioned,” Workforce Management (accessed on December 26, 2006.)

“Working When and Where You Want,” www.abcnews.com, October 3 2005.

9

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

Analysts‟ perceptions on the efficacy of ROWE were mixed. Jim Donahue (Donahue), a human

resources consultant at Hewitt Associates, a human resources consultancy firm, was in favor of

ROWE. According to him, although several companies had flexible work arrangements in place

for their employees, most of them restricted flexibility to a small percentage of the workforce. He

believed that the commitment of a company of Best Buy‟s size would serve to popularize flexible

arrangements for a greater part of the workforce. “A Fortune 100 employer doing this gives it a

whole bunch of legitimacy, versus coming from a consultant or from an academic who says, „This

is a good thing,‟” said Donahue.29

Others analysts however, thought ROWE could create a lot of chaos at large corporations. Paul

Rupert (Rupert), a flexibility consultant at Washington DC-based Rupert & Co., said that Best Buy

was in a position to experiment with its systems as the average age of its workforce was relatively

low. He said that as most of the managers at Best Buy were in their 30s (the average age of the

workforce at Best Buy in 2006 was 3630), it was relatively easy for the company to implement

change. However, employees at many other corporate headquarters were in their 50s and 60s, and

it would be much more challenging to implement change at these places, he felt.

Some analysts said it was difficult to determine whether increased productivity under ROWE came

about because the company had changed to ROWE or simply because it had changed. They said

that anything that was different from „the usual grind‟ could lead to a temporary spurt in

productivity. But when it became the new standard, employees could fall back into a rut.

Despite the arguments against ROWE, Best Buy was determined to press on with it. The company

announced that all the 4,000 employees working at Best Buy‟s corporate offices would be brought

under ROWE by the end of 2007.31 Whether ROWE becomes the new workplace paradigm or

leads to chaos still remains to be seen.

29

30

31

Annie Baxter, “Best Buy‟s Newest Product – Worker Satisfaction,” http://minnesota.publicradio.org, December 11,

2006.

Michelle Conlin, “Smashing the Clock,” BusinessWeek, December 11, 2006.

Michelle Conlin, “Smashing the Clock,” BusinessWeek, December 11, 2006.

10

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

Exhibit I

Best Buy Logo

Source: www.wikipedia.com

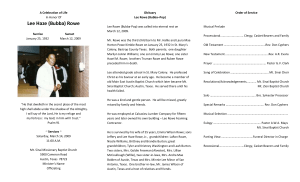

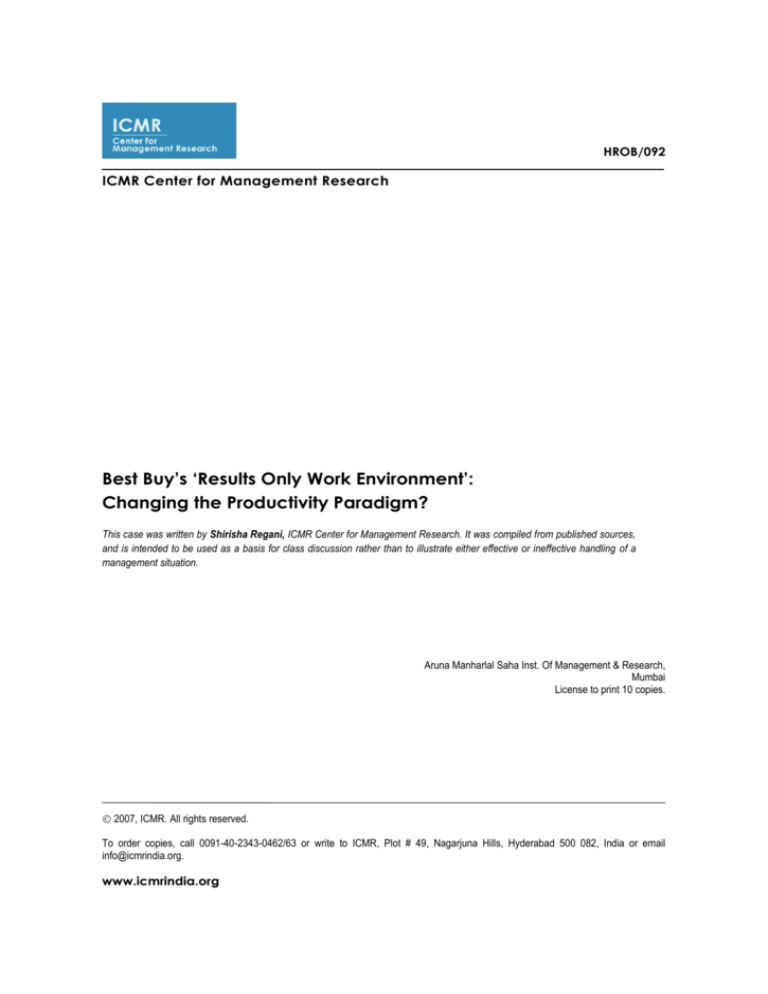

Exhibit II

Annual Income Statement

(All amounts in millions of US dollars except per share data)

Feb 06

Feb 05

Feb 04

Revenue

30,848.0

27,433.0

24,547.0

Cost of Goods Sold

23,122.0

20,938.0

18,350.0

7,726.0

6,495.0

6,197.0

25.0%

23.7%

25.2%

5,626.0

4,594.0

4,508.0

456.0

459.0

385.0

Operating Income

1,644.0

1,442.0

1,304.0

Operating Margin

5.3%

5.3%

5.3%

Nonoperating Income

107.0

1.0

--

30.0

--

8.0

1,721.0

1,443.0

1,296.0

581.0

509.0

496.0

Net Income After Taxes

1,140.0

934.0

800.0

Continuing Operations

1,140.0

934.0

800.0

--

50.0

(95.0)

Total Operations

1,140.0

984.0

705.0

Total Net Income

1,140.0

984.0

705.0

Net Profit Margin

3.7%

3.6%

2.9%

Diluted EPS from Total Net Income ($)

2.27

1.96

1.43

Dividends per Share

0.31

0.28

0.07

Gross Profit

Gross Profit Margin

SG&A Expense

Depreciation & Amortization

Nonoperating Expenses

Income Before Taxes

Income Taxes

Discontinued Operations

Source: www.hoovers.com

11

Best Buy’s ‘Results Only Work Environment’: ….

References & Suggested Readings:

1. “Best Buy Sells Musicland Unit,” New Mexico Business Weekly, June 16, 2003

2. Jyoti Thottam, “Reworking Work,” Time, July 25, 2005.

3. Ariana Eunjung Cha, “Profiling for Profit: Stores Cater to Customer Types,” The

Washington Post, August 22, 2005.

4. “Working When and Where You Want,” www.abcnews.com, October 3 2005.

5. Matthew Boyle, “Best Buy‟s Transformative CEO,” Fortune, March 23, 2006.

6. Matthew Boyle, “Best Buy‟s Giant Gamble,” Fortune, March 29, 2006.

7. Lesley Stahl, “Working 24/7,” CBS News, July 23, 2006.

8. George Anderson, “Best Buy Realigns

www.retailwire.com, December 7, 2006.

Work

Environment

for

Results,”

9. “Best Buy Rethinks the Idea of the Workplace,” insidethecubicle.blogs.com, December 7,

2006

10. Michelle Conlin, “Smashing the Clock,” BusinessWeek, December 11, 2006.

11. Michelle Conlin, “Let them Go,” BusinessWeek, December 11, 2006.

12. Michelle Conlin, “Off the Leash,” BusinessWeek, December 11, 2006.

13. Michelle Conlin, “How to Kill Meetings,” BusinessWeek, December 11, 2006.

14. Lynne LaMaster, “Unplugging the Time Clock at Best Buy,” That‟s Crispy, December 11,

2006.

15. Annie Baxter, “Best Buy‟s Newest Product

http://minnesota.publicradio.org, December 11, 2006.

–

Worker

Satisfaction,”

16. Don Loper, “Best Buy‟s Results Oriented Work Environment, a Workplace Revolution

in the Making,” www.donloper.com, December 13, 2006.

17. Melanie Turek, “Working from the Woods? At Best Buy, Making the Dream a Reality,”

www.collaborationloop.com, December 18, 2006.

18. Patrick J. Kiger, “ROWE‟s Adaptability Questioned,” Workforce Management (accessed

on December 26, 2006.)

19. “Case Study,” http://culturerx.com (accessed on January 8, 2006)

20. “How Best Buy Realized That Productivity Doesn't Necessarily Mean Being in The Office At

8am,” www.techdirt.com, December 5, 2006.

21. www.wikipedia.com

22. www.hoovers.com

23. www.bestbuy.com

12