Criminal Procedure (Simplification) Project Six

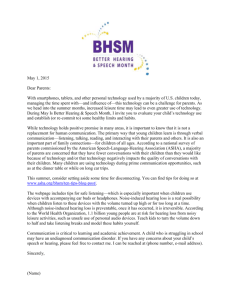

advertisement