is the aia the end of grace? - New York University Law Review

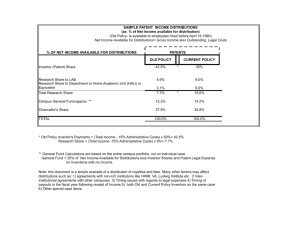

advertisement