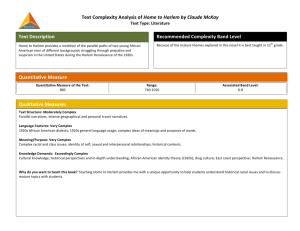

An Arguement for Claude McKay's Significance in the Harlem

advertisement

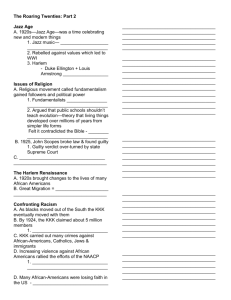

David Arteaga 1 Spokesman for the Oppressed: An Argument for Claude McKay’s Significance in the Harlem Renaissance The term “Harlem Renaissance” is somewhat anomalous. Harlem refers to the predominantly African-American neighborhood within the borough of Manhattan. Renaissance, according to its French roots, means “rebirth” of art and literature.1 Via word-by-word analysis, Harlem Renaissance strictly means a cultural rebirth in Harlem. Nonetheless, it is difficult to separate this cultural movement from its socio-political aspects. It is thus fitting that Claude McKay heavily participated in the Harlem Renaissance, for his character encompasses multidimensional artistic and political facets as well. This essay examines Claude McKay and his complex relationship with the Harlem Renaissance. In fact, this essay seeks to argue that Claude McKay became a prominent leader in the Harlem Renaissance through his publication of Harlem Shadows because the novel successfully expresses the voice of African Americans during the 1920s. The Harlem Renaissance began in 1920. Because northern factories lacked the workforce needed to meet the industrial demands of World War I, many African Americans in the South migrated north in search of work. With this influx of African Americans, northern cities experienced the creation of a “new cultural landscape,” a landscape in which African American writers, artists, musicians, and intellectuals were introducing works to previously whitedominated cultures.2 Although the creation of a new cultural landscape occurred nationwide, the Harlem Renaissance derives its name from the neighborhood of Harlem in the borough of Manhattan, New York City. It was to this neighborhood, in particular, that many African American artists and intellectuals moved. Well-known African American artists who lived in Harlem during the 1920’s include but are not limited to: Paul Robeson, Count Basie, Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Augusta Savage. The goal of these African Americans and other David Arteaga 2 participants in the Harlem Renaissance was “to find outlets for group expression and selfdetermination as a means of achieving equality and civil rights” (History.com Staff). In other words, the Harlem Renaissance was a means by which African Americans established a national black identity through various forms of artistic self-expression — dance, poetry, literature, music, theater, and the arts. Although the Harlem Renaissance was short-lived, coming to an end at the start of the Great Depression in 1929, it established a stepping ground for a new era of American politics. Claude McKay’s history with the Harlem Renaissance is complex. Let us examine the trajectory of his life step-wise, for this knowledge is critical in order to analyze McKay’s role and significance in the movement. Claude McKay was born in Jamaica on September 15, 1889. According to Max Eastman, McKay was raised by a “wise and beautiful mother” and lived an early, “happy tropic life of play and affection” (McKay and Eastman xi). As McKay grew older, however, he became attracted to America, “a new land to which all people who had youth and a youthful mind turned” (quoted in Cooper 298). Thus in 1912, at the age of 23, McKay moved to the United States with plans to learn scientific farming. McKay’s agriculture studies lasted only two years, however. At first, McKay studied at the Alabama Tuskegee Institute, but strong southern racial prejudice influenced his transferring to Kansas State College. In 1914, McKay left Kansas State College, for he wished to pursue a literary career in New York City. McKay landed in Harlem where he worked job-to-job as a porter, janitor, and waiter in order to pay for his living. After his publication of “The Harlem Dancer” and “Invocation,” McKay gained national publicity. This recognition afforded his meeting Max Eastman, editor of The Liberator, an American Marxist magazine. Thanks to Eastman, McKay not only worked for The Liberator but also began to identity with the bohemian radicals of Greenwich Village. This work with The David Arteaga 3 Liberator afforded McKay a new life of luxury.4 In 1919, he travelled to England to write for Sylvia Pankhurst’s socialist paper The Workers’ Dreadnought. In 1921, McKay returned to Harlem and briefly worked as co-editor of The Liberator. During this period, McKay published Harlem Shadows and befriended leading African American intellectuals James W. Johnson and W. E. B. Dubois. At the end of 1922, McKay travelled to Russia, where he was very popular amongst the political and literary elite.4 In fact, McKay met Trotsky, Sen Katayama, and various Russian writers. After time in Russia, McKay spent twelve years in Europe until his return to America in 1934. It is evident that McKay’s biography during the 1920’s is indeed complex. Certain critics have examined this biography and made arguments that belittle McKay’s role in the Harlem Renaissance. I plan examine these arguments and refute them step-wise. First, it has been argued that Claude McKay’s absence from Harlem during the 1920s belittles his significance in the Harlem Renaissance.2,5 McKay was absent from Harlem from 1919-1921 during his work in England and from 1922-1934 during his travels in Russia & Europe. Nonetheless, it is arguable that although McKay was physically absent from Harlem for most of the Harlem Renaissance, he was spiritually and emotionally present. In his autobiography A Long Way From Home, McKay describes a comfort that overcomes him when he returns from England to Harlem in 1921: “A wave of thrills flooded the arteries of my being, and I felt as if I had undergone initiation as a member of my tribe. And I was happy. Yes it was a rare sensation again to be just one black among many. It was good to be lost in the shadows of Harlem again” (79). McKay’s description of Harlem as “my tribe” establishes a connection between Harlem and Jamaica. This connection suggests that Harlem is McKay’s trans-oceanic home, away from his native Jamaican upbringing. Furthermore, it should be noted that McKay David Arteaga 4 did not leave Harlem with mal-intention. In A Long Way From Home, McKay explains that his desires to travel in 1922 were not motivated by a desire to leave Harlem; rather, they were motived by a dominant urge: “All I had was the urge to go, and that discovered the way” (121). Second, it could be argued that McKay’s experiences with wealth and white elite alienates him from most African Americans, and for this reason, he is not a representative African American voice in Harlem Shadows. It is true that McKay’s literary fame afforded his association with powerful white elite.4 For example, during his time with The Liberator, McKay worked in close association with many white radicals living in Greenwich Village. Moreover, during his travels in Russia, McKay was well received amongst white Russian political and literary leaders. In fact, McKay was invited to exclusive Russian party circles.4 Nonetheless, McKay suffered from the trials of racial prejudice before and after his literary success. As a child, McKay learned of his family’s abduction in Madagascar and subsequent voyage to Jamaica where they were sold as slaves at auction.3 In addition, McKay suffered from racial prejudice while learning at the Alabama Tuskegee Institute. However, perhaps McKay’s most poignant experience with racism occurred in 1921, after he had earned national literary recognition. McKay and a white co-worker at The Liberator were invited review the New York play He Who Gets Slapped. Although both were dramatic guests, McKay was sent to the second balcony while his co-worker was sent to the first row. McKay wrote about his emotions while sitting on the second balcony: “Apart, alone, black and shrouded in blackness, quivering in every fiber, my heart denying itself and hiding from every gesture of kindliness, hard in its belief that kindliness is to be found in no nation or race” (quoted in Tillery 56). These experiences give McKay’s voice strong credibility and reliability as he seeks to describe the sentiments of African Americans suffering from racial prejudice in Harlem Shadows. David Arteaga 5 Third, McKay has been criticized for using traditional English structure and language rather than native dialect in Harlem Shadows.5 During the Harlem Renaissance, African American writers sought to use black vernacular and folk expression to deform traditional white literary structure.5 McKay’s poetic structure, however, is strongly traditional. In fact, in Harlem Shadows McKay often utilizes the English sonnet. In light of these criticisms, Hathaway argues that although McKay uses antimodernist structure, he conveys modernist themes: “McKay provided an alternative model of modernist writing during the period by addressing distinctly modern themes, particularly surrounding race and urbanization, in an antimodernist form” (58). In other words, although Harlem Shadows features traditionally structured poetry, the novel is distinctly African American, for it discusses modern themes (read: “modern” for the 1920’s) concerning African Americans in Harlem. Fourth, it has been argued that McKay’s disagreements with major figures of the Harlem Renaissance diminishes his role in the movement.5 Being a left-wing radical, McKay disagreed with the values of conservative African Americans and often called for more activism on behalf of apolitical African American leaders. Despite these disagreements, whites, blacks, liberals, and conservatives praised Harlem Shadows upon its publication in 1922.6 In fact, the novel was very well received by conservative African American leaders Walter White and James Weldon Johnson. Walter White, Executive Secretary of the NAACP from 1931-1955, acknowledged McKay as “without doubt the most talented and versatile of the new school of imaginative, emotional Negro poets” (quoted in Tillery 54). James Weldon Johnson, executive secretary of the NAACP from 1920-1930, gave McKay more flattering praise: “Mr. McKay is a real poet and a great poet … No Negro has sung more beautifully of his race than McKay and no poet has ever equaled the power with which he expresses the bitterness that so often rises in the heart of his David Arteaga 6 race … The race ought to be proud of a poet capable of voicing it so fully. Such a voice is not found everyday … What he has achieved in this little volume sheds honor upon the whole race” (quoted Tillery 54). It is thus arguable that Harlem Shadows’ universal reception, especially from McKay’s political antagonists, transcends the disagreements between McKay and major figures of the Harlem Renaissance. Lastly, it has been argued that because McKay is not African American, his voice on behalf of African Americans in Harlem is weakened.5 It is arguable, however, that McKay identifies with many African Americans in Harlem, for he like they travelled from tropic homes to New York City. As a result, poems in Harlem Shadows that express McKay’s urge to return to the tropics of Jamaica (i.e. “Home Thoughts,” “Homing Swallows,” “The Plateau”) reflects African Americans’ urge to return to the warmer, more tropic areas of the South. Although I have discussed these arguments and defended them on McKay’s behalf, I believe that they are mute when one considers the goal of the Harlem Renaissance, McKay’s intentions in publishing Harlem Shadows, and discussions of literary ownership. In A Long Way from Home, McKay discusses his emotions after the publication of Harlem Shadows: “The publication of my first American book uplifted me with the greatest joy of my life experience … I had achieved my main purpose” (117). He describes the novel as a “sheaf of songs” and claims that, “I sang in all moods, wild, sweet and bitter” (116). In other words, McKay’s “main purpose,” or authorial intent, in Harlem Shadows was to publish an American novel featuring his “songs,” or self-expression. It is arguable, however, that Harlem Shadows embodies not only McKay’s individual expression but also the expression of all people in Harlem, for as Wimsatt and Beardsley argue, poems belong to neither the poet nor the reader. Rather, poems belong to the public: “The poem is not the critic’s own and not the author’s. … The poem belongs to the David Arteaga 7 public. It is embodied in language, the peculiar expression of the public, and it is about the human being, an object of public knowledge” (470). If poems belong to the public, Harlem Shadows, a series of lyrical poems that describe the life of an African American in Harlem, certainly belongs to the inhabitants of Harlem. We should not be concerned with the reader’s thoughts concerning Harlem Shadows or McKay’s thoughts concerning Harlem Shadows. The novel belongs to the people of Harlem during the 1920’s and is a means by which those inhabitants raised national awareness of their identity. Thus, McKay’s publishing Harlem Shadows agrees with and promotes the intent of the Harlem Renaissance — African American self-expression to raise national black identity — regardless of McKay’s absence from Harlem during the 1920’s, association with Anglo-Saxon elite, use of traditional poetic structure, political disagreements with Harlem Renaissance leaders, and non African American label. The voice that McKay expresses in Harlem Shadows is emotionally diverse. Poems range from expressions of helplessness, despair, & suffering to expressions of resiliency, strength, & protest. According to Hathaway, racism elicited such polarized emotions during the early 20th century, for although racism was repressing, it also provided an adversity that united African Americans.5 Let us first examine McKay’s expressions of helplessness, despair, & suffering in Harlem Shadows. In “In Bondage,” McKay reveals African Americans’ hopelessness to escaping racial prejudice. For instance, although McKay dreams of a peaceful, “leisurely” world, “where life is fairer, lighter, less demanding,” he acknowledges that such life is unrealistic, for he feels eternally bound to the condition of slavery under white men, who themselves are slaves to an insatiable lust for power: “But I am bound with you in your mean graves,/ O black men, simple slaves of ruthless slaves” (McKay 28). Moreover, in “The Castaways,” “The Tired Worker,” and David Arteaga 8 “Dawn in New York,” McKay reveals how urbanization has converted Harlem into a modern wasteland.5 In “The Tired Worker,” McKay dreads the dawn, for it sheds light upon the ruins of inner city Harlem: “O dawn! O dreaded dawn! O let me rest/ Weary my veins, my brain, my life! Have pity!/ No! Once again the harsh, ugly city” (McKay 44). Lastly, McKay voices the despair of African American women, who under the subjugation of being black and female often sold their bodies to make a living in the 1920s. For instance, in “Harlem Dancer” McKay, sitting amongst a crowd of men in a strip club, notices that an African American female dancer smiles while she dances in order to mask her inner sadness: “But looking at her falsely-smiling face/ I knew her self was not in that strange place” (McKay 42). Despite these emotions of despair, McKay’s protest poetry in Harlem Shadows reflects a strong will to fight racial prejudice. In fact, according to Smith, Harlem Shadows is “saturated with protest” against policies of discrimination (272). For example, in “Enslaved” McKay calls for the destruction of the white man’s world. In fact, he pleas angels to “consume/ The white man’s world of wonders utterly/ … To liberate my people from its yoke!” (McKay 32). The most famous of McKay’s protest poetry, however, is “If We Must Die.” McKay wrote the poem in response to the race riots of 1919. As African Americans moved to northern cities in search of jobs during WWI, whites and blacks not only interacted at the work place but also in social settings. African Americans were now attending theater shows and visiting beaches that were previously visited by only whites.8 Smith explains that whites did not enjoy these social changes, and resentment resulted in race riots in major American cities. In “If We Must Die” McKay encourages African Americans to be courageous in their fight for equality: “Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,/ Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!” (McKay 53). Looking at the draft of “If We Must Die,” it is evident that Claude McKay intended for the poem David Arteaga 9 to be emphatic. The draft featured only one hand-written correction: “accursed” was changed to “accurséd.”9 The addition of this accent mark changes the two-syllable word “accursed” to a three-syllable word “accurséd.” This extra syllable draws greater attention to “accurséd” for two reasons. First, “accursed” does not normally have an accent; the unfamiliarity of the accent’s presence draws attention to the word. Second, while reading the poem, the accent’s creation of an additional syllable requires that the reader slow down while saying “accurséd.” This change is small, yet it is indicative of McKay’s intentions with the publication of “If We Must Die.” Just as he sought to draw greater attention to the word “accurséd” through the addition of an accent, McKay also sought to draw greater attention to African American identity, racial prejudice, and national inequality in Harlem Shadows. “This is not the poetry of submission or acquiescence; this is not the voice of a gradualist; or is this the native dialect of the jackass. It is one of scorching flame, a voice conscious of persecution, that dares to strike back with vehemence” (Smith 272). McKay’s self-expression in Harlem Shadows on behalf of African Americans was strong. In fact, as Smith describes, this self-expression dared to “strike back” against racial injustice. As a leading spokesman of an oppressed race, McKay facilitated the establishment of a national African American voice, a voice that sought to emphasize not only the injustices of racial prejudice but also the courage, strength, and resiliency of African Americans. It was this voice amongst others that “forged a path for future generations and ushered in a new era of American culture and politics” during the early 20th century (History.com Staff). For this reason, Claude McKay is a prominent, praiseworthy, and admirable leader of the Harlem Renaissance. David Arteaga 10 Citations 1 The Renaissance. “Wikipedia.” Wikimedia Foundation, 22 Nov. 2014. Web. 23 Nov. 2014. 2 McKay, Claude. A Long Way from Home. Ed. Gene Andrew Jarrett. Reprint ed. New York: Rutgers UP, 1937. Google Books. Web 9 Nov. 2014. 3 McKay, Claude, and Max Eastman. Harlem Shadows: The Poems of Claude McKay. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1922. Print. 4 Cooper, Wayne. “Claude McKay and the New Negro of the 1920’s.” Phylon (1960-) 25.3 (1964): 297-306. JSTOR. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. 5 Hathaway, Heather. “The ‘Modernism’ of Claude McKay’s Harlem Shadows.” Race and the Modern Artist. 54-68. Google Books. Web. 16 Nov. 2014. 6 Tillery, Tyrone. Claude McKay: A Black Poet’s Struggle for Identity. Amherst: U of Massachusetts, 1992. Google Books. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. 7 Jr., W. K. Wimsatt. “The Intentional Fallacy.” The Sewanee Review 54.3 (1946): 468-88. JSTOR. Web. 10 Nov. 2014. 8 Smith, Robert A. “Claude McKay: An Essay in Criticism.” Phylon (1940-1956) 9.3 (1948): 270-273. JSTOR. Web. 17 Nov. 2014. 9 McKay, Claude. “If We Must Die.” Draft. Yale University. New Haven. n.d. Print. 10 “Google Ngram Viewer.” Google Ngram Viewer: Aframerican. Web. 30 Nov. 2014.