1. Describe the ways in which Berlioz's Symphonie

advertisement

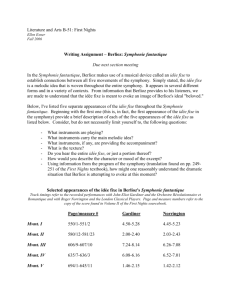

CHAPTER 20 1. Describe the ways in which Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique reflects Romanticism. How does it differ from symphonies you have studied in earlier chapters? In what ways is the idée fixe presented throughout the symphony? How do the program and the idée fixe influence the form of the work? Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique is a paragon of musical Romanticism for many reasons. First, it is profoundly influenced by literature. In contrast to earlier symphonies, it follows an extramusical narrative arc devised by the composer, thus making it an early example of “program music.” (Music without a literary subtext became known as “absolute music.”) Further, Berlioz’s vaguely autobiographical premise was itself indebted to a range of literary influences, and this program was given to audiences in advance of performance to help guide their listening. The “story” of Symphonie fantastique is filled with many common Romantic tropes, including love, obsession, mystery, the otherworldly, and the grotesque. To capture these qualities in sound, Berlioz relied on an unprecedentedly large orchestra and innovative scoring techniques. The idée fixe undergoes a series of transformations over the course of the piece that reflect the development of the story. Its first statement is wistful and filled with longing; it sonically mirrors the palpitations of a fluttering, love-struck heart as the hero of the story first encounters his beloved. The theme goes on to represent the characters’ fleeting connection in the midst of a ball; a pastoral setting; a grisly execution; and finally, in a warped and grotesque version that parodies a dance tune, a witches’ Sabbath. The program and idée fixe motive inspire and shape every aspect of the symphony’s form. It does not unfold like earlier symphonies, which are typically structured on a four-movement pattern dictated by musical considerations; rather, Symphonie fantastique is an “instrumental drama” that, like opera, is organized around the text. 2. Discuss Mendelssohn’s treatment of literary and pictorial themes in his music. Many of Mendelssohn’s best-known compositions are based on literary themes; however, his treatment of such themes differs considerably from Berlioz. In Mendelssohn’s literature-inspired works, most notably the overtures—including A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, Hebrides, and Fair Melusine—music is meant to portray the general mood and scenery of the literary story and setting, not its narrative arc. Mendelssohn was more concerned with musical evocation than musical storytelling. 3. Describe the significance of chorales in German music, especially in Mendelssohn’s Paulus. In what respects is Paulus a nationalistic work? How would you characterize the kind of nationalism it expresses? In their stark simplicity, chorales are associated in German music with community (i.e., their simplicity makes them accessible to all church-goers, not just the musically talented). Their uniquely communal nature helped to turn the chorale from a strictly Lutheran worship genre to the musical property of all Germans. Indeed, it became a symbol of Germanness. Mendelssohn exploited this connotation in Paulus, where prominent chorales function both as an autobiographical statement of allegiance to Christianity (Mendelssohn was born into the Jewish faith), and as a symbol of German national identity. Paulus thus reflects a German nationalism rooted in a folksy idea of spiritual community. 4. How did Wagner’s essay “Judaism in Music” represent a change in the nature of nationalism? Wagner’s essay claimed that national belonging was not a matter of culture—that is, of allegiances and values—but rather an issue of nature (i.e., people’s essential, immutable ethnic and racial origins). Nationalism was thus an exclusionary concept: Those who were not racially “German” (such as the Jews) were viewed by Wagner and his followers as fundamentally exempt from inclusion in the national community. 5. Describe the many ways in which Schumann’s music and critical writings were influenced by literature. Schumann modeled some of his compositions on works of literature. Moreover, many of his pieces are structured like books, with the sorts of formal divisions usually reserved for texts (e.g., prologues and epilogues). Schumann’s “fragment” aesthetic is similarly influenced by literature: Texts that are incomplete and fragmentary inspired him to create their musical analogy with fleeting, mysterious gestures that engage the listener’s memory without offering any real answers. Most obviously, however, Schumann’s embrace of literary models is exhibited in his song cycles, which feature the poetry of some of the finest writers of the day, particularly Heinrich Heine. His critical writings were equally influenced by literature. Many of his articles took the form of a narrative, with allegorical connotations, invented interlocutors (notably “The League of David”), and a colorful cast of alter egos, including the wild and passionate Florestan, sensitive and gentle Eusebius, and judgmental Master Raro. 6. Describe Schumann’s attitudes toward program music, as expressed in his own musical works and in his review of Symphonie fantastique. Schumann had an ambivalent opinion of program music. On the one hand, he liked to fill his music with subtle literary references. For instance, his Fantasy (Op. 17) was originally conceived with programmatic titles for each of its three movements, and an epigraph from a famous Romantic poet (Schlegel). However, he withdrew all titles at the last minute while also leaving an asterism in the score to indicate that something had been omitted. This created an enigma that players and audiences were encouraged to solve for themselves. DCS Valued Customer 3/5/12 6:03 PM Comment [1]: AU: Should this say “leaving an asterism in the score”? On the other hand, Schumann abhorred giving the performer and audience too much extramusical context for a piece of music. To him, overtly programmatic texts constrained the composer’s freedom and limited the possible range of musical meaning available to audiences. This view is illustrated in his critiques of Symphonie fantastique (a piece he otherwise adored). 7. How does Schumann’s setting of Dichterliebe reflect a sensitivity to the poetry? The emotional ambiguity characteristic of Heine’s poetry is reflected in Schumann’s harmonic strategies to elide stable conclusion (e.g., “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai,” which pivots uneasily between two chromatic neighbors and ends with an unresolved dominant seventh). He also uses music to contradict the words of the poem; for example, in the final song (“Die alten, bösen Lieder”) he belies the morose lyrics with music that parodies a cheerful tune. In this way, Schumann’s settings were musical interpretations of their literary sources, not simply mirrors onto their literal content. 8. What are some reasons that women composers did not flourish fully in the nineteenth century? Cultural attitudes in the nineteenth century were patriarchal and restrictive to women. Women were expected first and foremost to be obedient wives and mothers; to many, a career as a composer constituted an intrusion upon these domestic duties, and should thus be avoided. For example, Fanny Mendelssohn, who was arguably just as musically precocious as her younger brother, was flatly forbidden by her father from publishing her compositions and performing publically. The virtuoso pianist Clara Wieck came to believe that “a woman must not wish to compose”: instead, she spent her days tending to her needy husband Robert Schumann and their eight children.