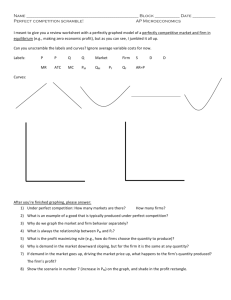

A Phenomenon Called 'Product Differentiation'

advertisement