Main Events during the Classical Period (1750-1825

advertisement

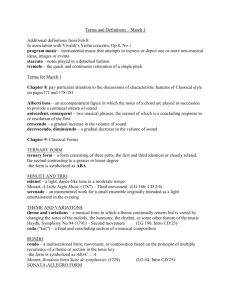

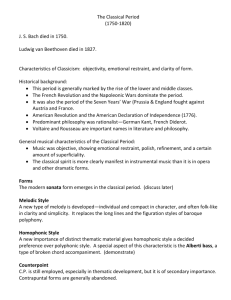

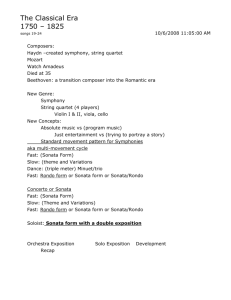

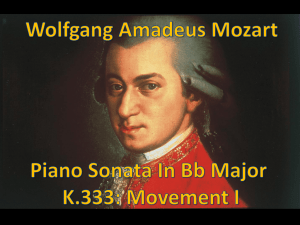

Main Events during the Classical Period (1750-1825) The Enlightenment (Age of Reason) – centred in France (though spreading across Europe), this was a cultural movement which promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuse from the Church and state. Mannheim School – orchestral techniques pioneered by the court orchestra of Mannheim which influenced composers such as Haydn, Hofmann and Mozart. 1760 – The Industrial Revolution (major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation and technology had a profound effect on the socioeconomic and cultural conditions of the time). 1769 – Watt’s Steam Engine is patented The American Revolution (1775-1783) 1775 – Electric battery invented by Volts 1776 – American Declaration of Independence 1787 – French Revolution the absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years as society underwent an epic transformation. 1796 – First vaccination Feudal, aristocratic and religious privileges evaporated as ideas about hierarchy and tradition succumbed to new Enlightenment principals. 1804 – Napoleon crowned Emperor 1819 – First steamship crosses the Atlantic Ocean 1821 – Faraday invents the electric motor and generator Robert Burns (1759-1796) Jane Austin (1775-1817) Music’s Place in Society - Composers The late 18th century was a period of great social upheaval. The breakdown of the old social order reached its culmination in the French Revolution (1789-99) and music ceased to be the exclusive preserve of pampered aristocrats or prelates (high ranking member of the Christian clergy). This radical social shift is reflected in the careers of the four great Classical composers. The Classical period boasts some of the best known classical composers in the history of Western music – namely Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. These composers formed what is now known as the First Viennese School of Composition and their works are still part of the core repertoire of classical music as a whole. Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) - Austrian Joseph Haydn was the eldest and longest lived of the ‘First Viennese School.’ Born when Bach and Handel were at the height of their fame, he outlived his friend Mozart by 18 years and saw his former pupil Beethoven well established in his own career. It was Haydn who practically invented the Classical musical forms of symphony, concerto, string quartet and sonata. Haydn’s life spanned a period of great social change. He was one of the last major musicians to work for a single aristocratic patron – in his case, the Hungarian Esterhazy family at the castle of Eisenstadt, 80km from Vienna. Haydn was isolated at Eszterhaza where there was no one to bother him, and he was, as he said, ‘forced to become original.’ By the 1780s his international reputation was spreading rapidly and he managed to negotiate a new contract with his employer which allowed him to compose for other patrons and have his work published. After the death of Prince Nikolaus Esterhazy in 1790, he was free to travel for the first time, spreading European reputation. During his long career, Haydn wrote 104 symphonies, string quartets, concerts, 15 surviving operas and 12 Masses. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) - Austrian By the age of four, Wolfgang began to study keyboard and composition with his father. His elder sister Maira Anna was also a talented pianist. His father, Leopold, a talented violinist in the court orchestra of the Archbishop of Slazburg, saw it as his duty to exhibit his exceptional children to the world. Mozart wrote his first symphony at the age of eight and by nineteen was touring in his own right. He moved to Vienna in 1781 were he wrote some of his most celebrated work including his operas The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, Cosi fan Tutte and The Magic Flute (full of Masonic symbolism – it has been suggested that he paid for this with his life) where he displayed his talent for bringing characters to life and allowing them to express real human emotions through music. However, the Viennese audiences of the time did not always appreciate this. Mozart wrote 21 piano concertos, 41 symphonies, 24 string quartets and 17 Masses among other chamber work and concertos. For several years Mozart’s career of teaching, composing and giving concerts of his own works proved successful. However, Mozart had a reputation for his arrogance which made him many enemies, including the powerful court composer, Antonio Salieri. Saleri and his friends were intensely jealous of Mozart’s abundant talent as depicted in the Oscar-winning film Amadeus which asserts, somewhat unfairly, that he poisoned the composer. The final years of his brief life were a dismal catalogue of financial worry, constant moves to cheaper apartments and failing health. His last work was an anonymous commission for a Requiem Mass. As he worked on this, he became obsessed by the idea that it would be his own and that he was being poisoned (in fact he had advanced kidney disease). He died in his wife’s arms in 1791 but because he left little money he was given the cheapest possible funeral in an unmarked grave. Few mourners accompanied the cortege. The unfinished Requiem was completed after his death by one of his pupils. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) - German Mozart died in Vienna in 1791, a year before the 20 year old Beethoven arrived in Vienna, keen to make his name as a musician. By this time, the face of European society was changing fast. The French Revolution was in full swing and Austria – horrified at the treatment meted out the French monarchs, particularly Queen Marie Antoinette, a former Austrian archduchess – had declared war on France. For more than two decades, Europe would be ripped apart by war. While Mozart’s life had remained largely unaffected by international politics, Beethoven’s revolutionary artistic vision was shaped by the ideology and volcanic social change of the turbulent times in which he lived. In 1787, Beethoven had hoped to take lessons with Mozart who was much impressed by the young man’s talent. But his trip was curtailed by news of his mother’s serious illness. He found an influential patron who later persuaded the elector to allow Beethoven leave to study with Haydn in Vienna. Beethoven found that his lessons were not a great success but quickly began to make his name as a pianist with a formidable reputation for improvisation. Beethoven’s early works show his desire to push the boundaries of conventional compositional technique, to expand sonata form and to infuse his work with unheard-of drama and passion. During his life he developed the ‘symphonic ideal’ which Beethoven perfected at a stroke with his Third Symphony (dedicated to Napoleon) and further celebrated with his Fifth, Sixth, Seventh and Ninth. This was a revolutionary method of unifying the symphony through the development of short melodic fragments or motifs over the course of the work. Beethoven felt that the minuet and trio which traditionally constituted the third movement of a symphony had outlived its purpose and from the Second Symphony onwards, replaced with a faster, more dynamic and rhythmically propelled scherzo which still retains the ternary form structure with a slower, more lyrical middle section. By the age of 30, at the height of his career, Beethoven was forced to acknowledge that he was going deaf. For several years he tried to hide his hearing problems for social and professional reasons. During this time he composed some of his most famous and enduring work including his only opera Fidelio and Symphonies no.3-6. Symphony no.5 includes the famous ‘de de de derrr, de de de derrr’ motif and Symphony no.6, The Pastoral is one of the earliest symphonic examples of ‘tone painting,’ illustrating scenes of Austrian country life which was revolutionary for its time. In 1824, Beethoven unveiled his 9th symphony, bursting the bonds of convention by introducing into the finale a setting for solo voices and chorus of Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy.’ Beethoven died of liver disease in 1827 with 10,000 people said to have watched the funeral procession. The poet Franz Grillparzer spoke these words at his funeral, ‘[he is] the man who inherited and enriched the immortal fame of Handel and Bach, of Haydn and Mozart…Until his death he preserved a father’s heart for mankind. Thus he was, thus he died, thus he will live to the end of time.’ Sonata and Sonata Form Sonata Sonata Form Exposition First Subject Second Subject Development Recapitulation Bridge Transition Coda Variation Alberti Bass Modulation Dominant Tonic Scherzo Minuet and Trio Sequence Sonata: A work for solo piano, or a solo instrument accompanied by piano, in three or four movements. The typical structure is: i. Moderate tempo in sonata form. ii. Slow tempo. iii. Scherzo or Minuet and Trio. iv. Fast tempo. Sonata Form: Important form for Classical instrumental music. The structure is: i. Exposition. Introduces the two main themes which are known are the first subject and the second subject. These themes are written in different keys and are separated by a transition or bridge passage – a short piece of music which connects the two themes. The first theme is presented in the tonic while the second theme is often written in the dominant key (5th higher or 4th lower than the tonic). The Exposition may end with a brief coda – a short piece of music which rounds off the section. The Exposition will end in the dominant key. ii. Development. The composer develops the first and second subjects. Ideas from both subjects will be taken and developed. For example, he may take the opening notes of the first subject and create a sequence from these. The composer will modulate several times in this section before returning to the tonic at the end of this section. iii. Recapitulation. The first subject is repeated in a related key. The second subject, which was originally heard in the dominant, will now be heard in the tonic. The music will end with a coda – a short passage which rounds off the music. First Subject in Tonic (C) Bridge (Transition) linking the first and second subjects Second Subject in Dominant (G) Coda I (G) Developmen t Several modulations ending in the tonic (C) First Subject in a related key Exposition Development The composer presents the two themes (the first and second subjects) in the tonic and dominant keys. The first and second subjects are developed. For example, he may take ideas from both subjects and write a sequence, use imitation of the ideas between parts, combine ideas. There will be several modulations before returning to the tonic. Bridge (Transition) linking the first and second subjects Second Subject in Tonic (C) Coda II Recapitulation The first and second subjects are presented in the tonic before ending with a coda. Study Score – Movement I of Mozart’s Piano Sonata No.15 in C First subject Written in the tonic key of C major. Note the use of an alberti bass as an accompaniment in the first phrase. The second phrase begins with a sequence of scales. Transition I This passage continues the scalic movement, modulating to the dominant of G major (note the use of the F# accidental in bar 10) in bar 12. Second Subject Written in the dominant key of G. This theme uses a descending triadic figure whereas the opening theme uses an ascending triadic figure its first phrase. Transition II Reinforces the dominant key of G major which the second subject is written in. Codetta Short series of perfect cadences in the dominant key of G major. Development Having concluded the exposition in the dominant (G major), Mozart now starts the development in G minor (the dominant minor). He combines an idea from the codetta (derived from the broken chords found in the first phrase of both subjects, their accompaniments and the second phrase of the second subject) with the scalic passages found in the second phrase of the first subject and the first transition. The music modulates through the following keys – G minor, D minor, A minor – with imitation between two distinct voices. Modulations are achieving through tonic-dominant relationships (see score) before moving to the key of F major for the start of the recapitulation. Recapitulation The first subject is now heard in the key of F major. Transition I’ Starting in F major, this mirrors transition I. However, this time Mozart switches the voices, giving the scalic passage to the bass voice and chords to the treble voice. As in transition I, the music then modulates to the dominant before the one bar introduction to the second subject takes us to the tonic key (C). Second Subject As expected, the second subject can now be heard in the tonic of C major. Transition II’ This is the same as transition I except for the shift in key. Coda II Mirroring coda I, firmly establishing the tonic of C major. Chamber Music Chamber music: Music written for a small group of musicians with one player per part. Examples of this are a string quartet, a piano trio (typically a piano, violin and cello), a woodwind quintet, a solo instrument (flute, cello, violin, clarinet, etc) accompanied by the piano. Symphony Symphony Modulation Sonata Form Recapitulation Minuet and Trio Motif Unison Relative major Trio Minuet and Trio Triple time Exposition Development Scherzo Question and Answer Theme and Variations Scherzo Fugue Coda Compound Time Symphony: A large work for an orchestra usually in four movements. In the Classical period the movements were usually: i. Fast. Often written in sonata form. ii. Slow iii. Minuet and Trio (3 beats in a bar). This minuet was later replaced by a scherzo which is in triple time (3 beats in a bar or in compound time). iv. Fast Theme and Variations Theme and Variations Development Triplets Imitation Canon Sequence Coda Repetition Theme and Variations: The theme is a melody, a tune which is the main idea for a composition. In theme and variations, the theme may form a whole section of the composition. The variations occurs when the main theme or tune is altered, perhaps by adding extra notes, changing from major to minor or vice versa, changing harmony, rhythm,, time signature, or when the them is played in the bass, etc. Opera – Coloratura Opera Overture Aria Da Capo Aria Coloratura Recitative Chorus Opera: Drama set to music with soloists, chorus, acting and orchestral accompaniment. It normally performed in a theatre. Coloratura: Term for high, florid vocal singing which involves scales, runs and ornaments. Sometimes these passages were written down but often they were extemporised by the performer. Excerpts from Mozart’s ‘Queen of the Night’ aria from The Magic Flute NEW INVENTIONS!!! The Piano The pianoforte was invented around 1709 by Bartolomeo Cristofori, a harpsichord builder and keeper of the royal musical instruments in Florence. Early Cristorfi pianos looked and sounded like contemporary harpsichords and were half the size of modern pianos. The main difference between the piano and the harpsichord was that the strings of the former were struck by hammers rather than being plucked by quills as in the harpsichord. The earliest music for the piano was a sonata composed by Lodovico Giustini in 1732, the year after Cristofori’s death. The square piano was made in 1742 by Johann Sacher. Although cheaper to produce, the bass strings had to be short and were therefore weak in volume. In Britain, square pianos were made by Johannes Zumpe from 1760 and it was on one of these instruments that J.C.Bach (a son of J.S.Bach) gave his London recital. French builder Sebastien Erand improved the mechanics and sound of the instrument in the early 19th century. By the end of the 18th century the piano had become more than just a fashionable toy and was a living force in culture and entertainment in the homes of the wealthy. In 1739, Domenico del Mela experimented with the upright piano. About 1800 it was discovered that the soundboard could be dropped towards the floor, placing most of the string length behind the keyboard in front of the player’s knees, thereby decreasing the overall height of the instrument. In the 1830s the problem of short bass strings was solved with the invention of the overstrung piano in which shorter strings ran vertically and the bass strings crossed obliquely over them allowing for greater length. This method is still used today. Many experiments in the 18th century helped to develop the mechanics, function and sound created by the pedals. In addition, several changes took place with the types of materials used for the strings. Beethoven and Mozart would not recognise their music now as the ‘modern’ piano did not begin to appear until about 1850. The string of the early 19th century were still quite light and thin and at much lower tension than today’s models in which they are so rigid that they act like bars. To increase the volume of the instrument, makers increased the thickness of the strings. The Clarinet The clarinet was invented in the first few years of the 18th century by the renowned woodwind maker Johann Christoph Denner or his Jakob in Nuremburg. In 1809, Iwan Muller, one of the finest clarinettists of his day, brought out the prototype of his 13-keyed model pitched in B flat which was to become the standard instrument for the next hundred years. The final major modification occurred between 1839 and 1843 when clarinettist Hyacinthe Klose collaborated with the maker Louis-August Buffet to simplify the fingering system. Mozart was a massive fan of the clarinet, writing three important works for the clarinettist Anton Stadler – the Kegelstaff Trio, the Clarinet Quintet and the Clarinet Concerto.