'mummy said i don't remember anything'

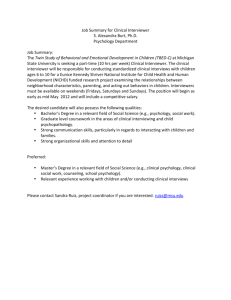

advertisement

‘MUMMY SAID I DON'T REMEMBER ANYTHING’: TRUE MEMORIES, FALSE MEMORIES AND CONSEQUENCES BY BIANCA GRUBOR LAW381: SUPERVISED LEGAL RESEARCH SUPERVISOR: GUY HALL WORD COUNT: 8,876 I dedicate all 8,876 words to an inspiring professor and even better friend. I am a better me because of you. 2 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 4 EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY AND MEMORY RECALL 5 TYPES OF MEMORIES 7 REPRESSED MEMORIES 7 SUPPRESSED MEMORIES 9 ALTERED MEMORIES 10 FALSE MEMORIES 12 OBSTACLES TO THE TRUTH 13 INTERVIEWER TONE 15 POSITION OF AUTHORITY 16 REPEATED QUESTIONING 17 TIME AND TYPE OF INTERVIEWER 19 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Protocol 22 EASTWOOD AND PATTON REPORT 23 INNOCENCE PROJECT 26 RONALD COTTON OR BOBBY POOLE? 27 CONCLUSION 28 REFERENCE LIST 30 3 I INTRODUCTION Since the 1990’s a ‘memory war’ has waged between scholars, physicians and scientists alike over the validity and reliability of different forms of memory.1 The issue has come into the fore of the legal arena because of its implications in the testimony of witnesses, namely the legitimacy of child witnesses.2 Children are being called as witnesses and are asked to recount certain events with as much accuracy as possible. There is the underlying belief or expectation that these memories have not been tampered with.3 This paper will start by demonstrating that eyewitness testimony accounts are not conclusive, and that memory is vulnerable to distortions; a problem that is further aggravated in the case of children. An evaluation of the different forms of memory, namely, repressed, suppressed, altered and false memories will demonstrate the degree of variations in the processing of memory. This paper will then evaluate how suggestibility and interviewer bias (through mechanisms such as: the tone of the interviewer; the interviewer’s relative position of authority; repeated questioning; and the timing of the interview) manipulate a child into changing, whether consciously or unconsciously, the recall of their memory. This paper will then consider the report titled ‘The Experiences of Child Complainants of Sexual Abuse in the Criminal Justice System’4 (Eastwood and Patton Report) that outlines some of the cross-jurisdictional concerns of children as witnesses. The Eastwood and Patton Report establishes trial processes can re-victimise children to such as point where the trauma has a strong negative impact on their ability to recall a memory 1 Lawrence Patihis, Lavina Y Ho, Ian W Tingen, Scott O Lilienfeld and Elizabeth F Loftus, ‘Are the “Memory Wars” Over? A Scientist – Practitioner Gap in Beliefs about Repressed Memory’ (2014) 25(2) Psychological Science 520. 2 Martine B Powell, Rebecca Wright and Carolyn H Hughes-Scholes, ‘Contrasting the perceptions of child testimony experts, prosecutors and police officers regarding individual child abuse interviews’ (2010) 11(3) Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 35. 3 Karen Saywitz and Rebecca Nathanson, ‘Children’s testimony and their perceptions of stress in and out of the courtroom’ (1993) 71 Child Abuse and Neglect 614. 4 C Eastwood, and W Patton, ‘The experiences of child complainants of sexual abuse in the criminal justice system’ (2002) Report to the Criminology Research Council, Canberra. 4 with the requisite degree of accuracy. This paper will conclude with an assessment of the United States initiative; the Innocence Project, a organisation dedicated to the exoneration of wrongfully convicted individuals due to inaccurate eyewitness testimonies. A brief look into the case study of Ronald Cotton will demonstrate the tragic consequences of misidentification, and how it serves as a stern reminder that memory recall is not as infallible as once perceived. II EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY AND MEMORY RECALL For centuries, eyewitness testimony has been used as a primary means for establishing the elements of a crime and determining the guilt of offenders. It is one of the most persuasive forms of evidence that can be presented to the court. It is assumed that humans can recollect most memories with a high degree of accuracy and detail and that recounting a memory is analogous to a video recorder – it is this assumption that poses real concerns for the courtroom.5 In light of recent developments in the study and understanding of memory, the tenacity of eyewitness testimony has been drawn into question. For decades, research and analysis was predominantly focused on quantity based memory assessments6 concentrating primarily on traditional memory recognition and input-bound measures. 7 In recent years, the studies have moved from this quantitative approach to that of a qualitative one; namely, the various ways in which memories can become distorted and erroneous.8 5 Tanya Rapus Benton, David F Ross, Emily Bradshaw, W Neil Thomas and Gregory Bradshaw, ‘Eyewitness Memory is still not Common Sense: Comparing Jurors, Judges and Law Enforcement to Eyewitness Experts’ (2006) 20(1) Applied Cognitive Psychology 119. 6 W Schneider and D F Bjorklund, ‘Memory’ in W Damon, D Kuhn, and R S Siegler (eds), Handbook of child psychology: Cognition, perception and language (Wiley, 1998) 475. 7 A Koriat and M Goldsmith, ‘Memory metaphors and the real-life/laboratory controversy: Correspondence versus storehouse conceptions of memory (1996) 19 Behavioral and Brain Sciences 221. 8 H L Roediger III, ‘Memory illusions’ (1996) 35 Journal of Memory and Language 91. 5 Eyewitness testimony can be unreliable given its dependence on the interaction between human senses and the brain’s processes in remembering these interactions.9 Memory is suggestible to many different sources of distortions that can affect the integrity of the original memory. 10 These problems are further exacerbated in the case of child witnesses. Historically, the judicial system has been cautious when relying on children’s evidence, attributable to the perceived inferiority of the accuracy of childrens’ memory11 and studies that revealed the high degree of suggestibility that children are vulnerable to.12 In general, the studies show that overall, children remember less than adults.13 Some of the explanations posited for this are; children have not developed cogent storage, encoding and retrieval faculties,14 they do not have established processes of semantic organisation15 and their metacognitive skills and knowledge structures are under matured, particularly at a young age.16 Since these early reports, studies have found that children’s ability for memory recall is not as weak and suggestible as originally thought – particularly when open-ended questions are used.17 Generally, studies have found that children will tend to remember 9 Joyce W Lacy and Craig E L Stark, ‘The Neuroscience of Memory: Implications for the Courtroom’ (2013) 14 Nature Reviews 649. 10 Ibid. 11 G S Goodman, ‘Children’s testimony in historical perspective’ (1984) 40 Journal of Social Issues 13. 12 Guy Whipple, ‘The observer as reporter: a survey of the “psychology of testimony”’ (1909) 6 Psychological Bulletin 161. 13 N Schneider and F E Weinert, ‘Universal Trends and Individual Differences in Memory Development’ in A de Ribaupierre (eds), Transition Mechanisms in Child Development: The Longitudinal Perspective (Cambridge University Press) 77. 14 C J Brainerd, ‘Three-state models of memory development: A review of advances in statistical methodology’ (1985) 40 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 387. 15 A L Brown, ‘Theories of memory and the problem of development: Activity, growth and knowledge’ (1979) Levels of Processing 240. 16 W Schneider and M Pressley, Memory development between 2 and 20 (Springer New York, 2nd ed, 1989). 17 W S Cassel, C E M Roebers and D F Bjorklund, ‘Developmental patterns of eyewitness responses to repeated and increasingly suggestive questions’ (1998) 61 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 127; C Peterson, ‘Children’s memory for medical emergencies: 2 years later’ (1999) 35 Developmental Psychology 1501; B V Marin, D L Holmes, M Guth and P Kovac, ‘The potential of 6 distressing or stressful events better than mundane every day events.18 Further, memories of events of a more personal nature are remembered with greater accuracy than if the child did not have a personal connection to the event.19 Additionally in younger children, the lack of preformed schemas makes them resistant to erroneous suggestions. A schema is an encapsulated network structure of multiple sensory episodes that can be altered by either assimilation or accommodation; essentially, where there are ‘missing pieces’ to a memory, children may fill these with pieces that are consistent with preformed schemas of a similar event.20 From the studies suggested above, it seems that the debate is not centred on one of quantity, the issue lies in that of the quality and whether or not children’s memories of events are as substantively accurate as they can be. III TYPES OF MEMORIES A Repressed Memories A repressed memory is one where an individual can recall, although it has been blocked from their conscious mind or they have been previously unable to recall it.21 children as eyewitnesses: A comparison of children and adults on eyewitness tasks’ (1995) 3 Law and Human Behavior 302; M R McCauley and R P Fisher, ‘Facilitating children’s eyewitness recall with the revised cognitive interview’ (1995) 80 Journal of Applied Psychology 512. 18 Kelly McWilliams, Rachel Narr, Gail S. Goodman, Sandra Ruiz and Macaria Mendoza, ‘Children’s memory of their mother’s murder: Accuracy, suggestibility, and resistance to suggestion’ (2013) 21(5) Memory 592. 19 M L Courage and M L Howe, ‘Autobiographical memory: Individual differences and developmental course’ in A Gruszka, G Matthews and B Szymura (eds), Handbook of Individual Differences in Cognition (Springer, 2010) 409; G S Goodman, L Rudy, B L Bottoms and C Aman, ‘Children’s concerns and memory functioning: Conclusions from a longitudinal study of family violence’ in M Howe, G S Goodman and D Cicchetti (eds), Stress, Trauma and Children’s Memory Development: Neurobiological, Cognitive, Clinical and Legal Perspectives (Oxford, 1990) 255. 20 William C Thompson, Alison K Clarke-Stewart and Stephen J Lapore, ‘What did the Janitor do? Suggestive interviewing and the accuracy of children’s accounts’ (1997) 21 Law and Human Behavior 422. 21 James Ost, Dan B Wright, Simon Easton, Lorraine Hope and Christopher C French, ‘Recovered memories, Satanic abuse, Dissociative Identity Disorder and false memories in the UK: A Survey of Clinical Psychologists and Hypnotherapists’ (2013) 19(1) Psychology, Crime and Law 10. 7 Simply put, a repressed memory is where; something happens that is so shocking that the mind grabs hold of the memory and pushes it underground, into some unaccessible corner of unconscious. There it sleeps for years, or even decades or even forever – isolated from the rest of mental life. Then one day it may rise up and emerge into consciousness.22 A debate has occurred between clinicians and academics over the veracity of repressed memories and what implications this debate will yield in future studies of memory. One side argues for the validity of repressed memories and their importance particularly in child sexual abuse cases, while the other side questions the probative value of a repressed memory and the method of its ‘re-discovery’.23 Advocates for the former side argue that skeptics of repressed memories misunderstand the true meaning of what constitutes a repressed memory.24 Freud originally stated that ‘the essence of repression lies simply in turning something away, and keeping it at a distance from the conscious’.25 Further, Freud proposed two types of repression: the first being a fully unconscious defence, where the mind subconsciously deletes the memory;26 while the second type concerns the conscious and active avoidance of the memory, namely suppression.27 While there is 22 Elizabeth F Loftus, ‘The reality of repressed memories’ (1993) 48(5) American Psychologist 525. 23 Ayesha Khurshid and Kristine M Jacquin, ‘Expert Testimony Influences Juror Decisions in Criminal Trials Involving Recovered Memories of Childhood Sexual Abuse’ (2013) 22(8) Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 952. 24 Chris R Brewin and Bernice Andrews, ‘Why it is Scientifically Respectable to Believe in Repression: A Response to Patihis, Ho, Tingen, Lilienfeld and Loftus (2014)’ (2014) Psychological Science 1965. 25 Martin A Conway, ‘Repression revisited’ (2001) 410 Nature 319. 26 C R Brewin and B Andrews, ‘Recovered Memories of Trauma: Phenomenology and Cognitive Mechanisms’ (1998) 18(8) Clinical Psychology Review 963; K S Bones and P Farvolden, ‘Revisiting a century-old Freudian slip – From suggestion disavowed to the truth repressed’ (1996) 119(3) Psychological Bulletin 374. 27 M C Anderson and E Huddleston, ‘Towards a cognitive and neurobiological model of motivating forgetting’ in R F Belli (eds), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol 58. True and false recovered memories: Towards a reconciliation of the debate (Springer, 2012) 67; M C Anderson and C Green, ‘Suppressing unwanted memories by executive control’ (2001) 410 Nature 366. 8 little evidence to support the existence of the first type of repressed memory,28 advocates argue that the second form of repression is not repression in the truest sense, but rather the suppression of memory.29 B Suppressed Memories Suppression is defined as an ‘active, deliberate conscious attempt to forget acutely painful or unacceptable thoughts and wishes by diverting attention to other matters’.30 This is a process where an individual can consciously shut down the retrieval of a particular memory.31 This process is voluntary and concerns conscious avoidance of the memory and any associated stimuli.32 Anderson and Green33 conducted the renowned ‘think/no think’ study with word pairs to determine if preventing awareness to an undesirable memory would inhibit its later retrieval. The study concluded that it is possible to actively suppress a memory both in the short and long term.34 Further the study also found that in the long term, the active avoidance of the memory inhibited its later recall and increased the number of times details in the memory were forgotten.35 28 David S Holmes, ‘The Evidence for Repression: An examination of sixty years of research’ in J L Singer (eds), Repression and Dissociation: Implications for Personality theory, Psychopathology and Health (University of Chicago Press, 1990) 96; Loftus, above n 21, 522. 29 This principle will be discussed later in the paper. 30 Jaqueline Kanvovitz, ‘Hypnotic Memories and Civil Sexual Abuse Trials’ (1992) 45 Vanderbilt Law Review 1190. 31 M C Anderson, R Bjork and E Bjork, ‘Remembering can cause forgetting: Retrieval dynamics in long term memory’ (1994) 20(5) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition 1074. 32 U Mayr and S W Keele, ‘Changing the internal constraints on action: the role of backward inhibition’ (2000) 129 Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 15. 33 Anderson and Green, above n 27, 368. 34 Ibid, 367. 35 Ibid. 9 While these studies are show promise in relation to memory suppression, the dependent variable were words, not a traumatic autobiographical memory.36 Conversely, some scholars have also found that individuals who have experienced more traumatic events in their lives had a greater degree of suppression than individuals who did not. 37 While the studies do not paint a consistent picture as to the nature of suppressed memories, one cannot ignore the findings above. Mechanisms do exist that can push unwanted memories out of an individual’s conscious and this can have permanent effects on the accessibility of these suppressed memories.38 Some advocates suggest that it is very unlikely that an individual can completely forget or repress a traumatic experience. 39 Additionally, studies suggest that traumatic experiences are in fact remembered clearly by victims as opposed to being repressed.40 Further, there is little scientific evidence to suggest that repeat traumatic events can be repressed, for years and then be made recoverable through therapeutic intervention.41 C Altered Memories Research demonstrates that individuals can unintentionally assimilate misinformation in an original memory from the recollections of others, which is known as the ‘misinformation effect’. The misinformation effect refers to the process when misleading information is presented to an individual in relation to a particular memory and that 36 Lawrence Patihis, Scott O. Lilenfeld, Lavina Y. Ho and Elizabeth F. Loftus, ‘Unconscious repressed memory is scientifically questionable’ (2014) Psychological Science, 1968. 37 Anderson and Huddleston, above n 27, 82. 38 M C Anderson and B A Spellman, ‘On the status of inhibitory mechanisms in cognition: Memory retrieval as a model case’ (1995) 102 Psychological Review 80. 39 Richard J McNally and Elke Geraerts, ‘A New Solution to the Recovered Memory Debate’ (2009) 4 Perspectives on Psychological Science 130; John F Kilstrom, ‘An Unbalanced Balancing Act: Blocked, Recovered and False Memories in the Laboratory and Clinic [review and commentaries] (2004) 11 Clinical Psychology: Science and Practise 38. 40 Ibid. 41 Holmes, above n 28, 85; Loftus, above n 22, 530. 10 misinformation is adopted as part of the original memory.42 The misinformation that is presented is generally given unintentionally either through the types of questions asked,43 feedback provided post interviews, 44 and body language and the like during the investigation process.45 Further, Fuzzy Trace Theory can be used to explain the misinformation effect. According to Fuzzy Trace Theory; Memories are duly recorded as verbatim representations of the exact and surface form of details, and in parallel as gist representations containing the general sense of what happened. Verbatim and gist traces are stored independently, and verbatim traces decay at a faster rate than do gist traces. Younger children rely more on verbatim than gist processing compared to older children…46 Fuzzy Trace Theory adopts a degree of the misinformation effect, namely that over time the original memory will fade due to the decay of the verbatim representations, and be replaced with a modified, tampered version. From a legal perspective, this can cause severe issues with the reliability of memories as their integrity can be compromised by their very source. 42 Elizabeth F Loftus, ‘Planting misinformation in the human mind: a 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory’ (2005) 12(4) Learning & Memory 365. 43 Elizabeth F Loftus, Eyewitness Testimony (Harvard University Press, 2nd ed, 1996) 55. 44 Positive feedback can reinforce the strength of an individual’s eyewitness testimony; C Semmler, N Brewer and G Wells, ‘Effects of post-identification feedback on eyewitness identification and nonidentification confidence’ (2004) 89 Journal of Applied Psychology 340. Contrariwise it can also decrease the confidence in an individual’s testimony; C Luus and G Wells, ‘The malleability of eyewitness confidence: co-witness and perseverance effects’ (1994) 79 Journal of Applied Psychology 722. 45 L Garrioch and C Brimacombe, ‘Lineup administrator’s expectations: their impact on eyewitness confidence’ (2001) 25 Law and Human Behaviour 312. 46 Kim P Roberts and Martine B Powell, ‘The roles of prior experience and the timing of misinformation presentations on young children’s event memories’ (2007) 78(4) Child Development 1140. 11 D False Memories A false memory is one where an individual can remember with vivid accuracy an event that never happened.47 False memories are described as errors of commission, unlike forgetting which is described as errors of omission.48 False memories are a result of losing the particular source of the original memory.49 Studies have demonstrated that children and adults will remember a plausible false event, suggesting that the cognitive processes involved in memory are similar.50 Fuzzy trace theory assumes that individuals store real memories, yet over time misinformation is moulded into the original memory, and this can result in the true memory being lost.51 The main elements necessary for the construction of a false memory are; that the event be a plausible one, that the individual believes in the event and constructs a memory from that, and that the individual has mistakenly attributed the constructed memory to actual memory.52 One of the main issues facing the judicial system is that, given the suggestibility of child witnesses, there is the potential for their evidence to be tainted by either other evidence or through juries and judges discounting part or whole of their testimony as they consider it unreliable.53 47 Cara Laney and Elizabeth F Loftus, ‘Recent Advances in False Memory Research’ (2013) 43(2) South African Journal of Psychology 141. 48 Marcia K Johnson, Carol L Raye, Karen J Mitchell and Elizabeth Ankudowich, ‘The cognitive neuroscience of true and false memories’ in R F Belli (ed), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol 58. True and false recovered memories: Towards a reconciliation of the debate (Springer, 2012) 18. 49 Maggie Bruck, Stephen J Ceci and Laura Melnyk, ‘Draw it Again Sam: The Effects of Drawing on Children’s Suggestibility and Source Monitoring Ability’ (2000) 77(3) Journal of Experimental Psychology 187. 50 Kathy Pezdek and Danielle Hodge, ‘Planting False Childhood Memories in Children: the Role of Event Plausibility’ (1999) 70 Child Development 891. 51 C J Brainerd, V F Reyna and E Brandse, Are children’s false memories more persistent than their true memories?’ (1995) 6 Psychological Science above 363. 52 Deryn Strange, Mathew P Gerrie and Maryanne Garry, ‘A Few Seemingly Harmless Routes to a False Memory’ (2005) 6 Cognitive Processes 239. 53 Elizabeth F Loftus, ‘Our Changeable Memories: Legal and Practical Implications’ (2003) 4 Nature Reviews Neuroscience 233. 12 IV OBSTACLES TO THE TRUTH The issue with legal practitioners eliciting information out of children is the manner in which that information is obtained and whether or not there have been suggestive influences on that. 54 Scholars posit that inadequate and inefficient interviewing techniques can increase the degree of suggestibility and contamination of memories in children.55 Suggestibility has both a broad and narrow definition. The broad definition concerns ‘the degree of which children’s encoding, storage, retrieval and reporting of events can be influenced by a range of social and psychological factors’.56 The narrower definition is ‘the extent to which individuals come to accept and subsequently incorporate post-event information into their memory recollections.’57 Studies have also pointed to the impact that interviewer bias and confirmation bias have on memory retrieval in children.58 Personal beliefs and expectations influence the way individuals think, encode and remember then world around them.59 People tend to interpret information presented to them in line with these held beliefs and expectations.60 Because of this, people actively seek information that confirms these beliefs and expectations rather than disconfirm it.61 54 Ibid. 55 Maggie Bruck and Stephen J. Ceci, ‘The Suggestibility of Children’s Memory’ (1990) 50 Annual Review of Psychology 420. 56 Ibid. 57 Ibid, 421. 58 Carolyn H Hughes-Scholes and Martine B Powell, ‘An examination of the types of leading questions used by investigative interviewers of children’ (2008) 31(2) Policing (Bradford): An International Journal of Police Strategies 212. 59 N J Rose and J W Sherman, ‘Expectancy’ in A W Kruglanski and E T Higgins (eds), Social Psychology: Handbook of basic principles (Guilford Press, 2007) 94. 60 Bradley D McAuliff and Brian H Bornstein, ‘Beliefs and expectancies in legal decision making: an introduction to the Special Issue’ (2012) 18(1) Psychology, Law and Crime 2. 61 C G Lord, L Ross and M R Lepper, ‘Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: the effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence’ (1979) 37(11) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2099. 13 Interviewer bias is characterised by interviewers holding a set of preconceived beliefs about an event, and how (at times) interviews are moulded to reflect these beliefs.62 Similarly, confirmation bias is defined as ‘the seeking or interpreting of evidence in ways that are partial to existing beliefs, expectations or a hypothesis in hand’.63 In relation to eyewitness testimony, during the interview and investigation phase, the interviewer seeks to confirm presumed particulars that the interviewee may have not disclosed.64 This bias causes interviewers to seek confirmatory information and disregard information that they believe to be inconsistent.65 This bias can affect the entire structure of the interview.66 Scholars point out that it is challenging to have an unbiased interviewer as they rarely conduct interviews, for example; on abuse, without prior background information that is indicative of the abuse.67 Even when trying to be neutral, interviewers can bias the questions asked in their interviews.68 One of the main factors that affect confirmation and interviewer bias is the preliminary information that the interviewer has before the interview, which can affect the style of the interview and can result in the increase in the rate of false witness 62 Ceci and Bruck, above n 55, 425. 63 R S Nickerson, ‘Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises’ (1998) 2 Review of General Psychology 175. 64 Stephen J Ceci and Maggie Bruck, ‘The role of interviewer bias’ in Stephen J Ceci and Maggie Bruck, Jeopardy in the courtroom: A scientific analysis of children’s testimony (American Psychological Association, 1999) 91. 65 Martine B Powell, Carolyn N Hughes-Scholes and Stefanie J Sharman, ‘Skill in interviewing reduces confirmation bias’ (2012) 9 Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling 126. 66 Ceci and Bruck, above n 55, 430. 67 N M Aarons, M B Powell and J Browne, ‘Police perceptions of interviews involving children with intellectual disabilities: a qualitative inquiry’ (2004) 14(3) Policing and Society 274. 68 Thompson, Clarke-Stuart and Lapore, above n 20, 408. 14 testimonies.69 Further, biased interviewers tend to ask more misleading questions with the presumed aim of obtaining ‘withheld’ information.70 Other factors, when coupled with interviewer and confirmation bias can increase the degree of suggestibility that a child is vulnerable to from an interviewer. These factors include; the interviewer’s tone, the relative position of authority, utilisation of repeated questioning and the timing and type of interview conducted. A Interviewer Tone The tone that an interviewer uses when interviewing a child can influence a child’s suggestibility. Children can be influenced by the tone and urgency of an interviewer that can lead to the child making false claims. The emotional tone moulds the linguistic interaction between interviewer and interviewee and influences the amount of false reports that are recorded. In one study, Thompson, Clarke-Stewart and Lapore 71 assessed the degree of suggestibility of young children in relation to the activities of a janitor. When a neutral interviewer questioned the children, their recollections of the event were consistent and correct. In interviews where the interviewer was overly supportive, the children provided as many accurate as inaccurate statements. Finally, in interviews where the interviewer was cold and authoritative, the rate of false statements was greater than accurate statements. The beliefs that children held about the janitor prior to the interview were altered and stored in their long-term memory.72 69 M B Powell, M Garry and N D Brewer, ‘Eyewitness Testimony’ in I Frekelton and H Selby (eds), Expert Evidence (Thompson Reuters, 2009) 28. 70 Gail S Goodman, Anupama Sharma, Sherry F Thomas and Mary G Considine, ‘Mother knows best: Effects of relationship status and interviewer bias on children’s memory’ (1995) 60 Journal of Experimental Psychology 200. 71 Thompson, Clarke-Stuart and Lapore, above n 20, 405. 72 Ibid, 421. 15 B Position of Authority The Social Demands/Response Biases Hypothesis predicts … that children are seen to make a deliberate, conscious decision to report the suggested item based on the social context and/or pragmatic cues presented to them at the time of testing.73 This hypothesis is used as an alternate model to explain suggestibility as children will report false evidence because of the social demands of the interview process.74 One of these social demands relates to the perceived credible and authoritative position of the interviewer to the child.75 Studies have found that children have a tendency to adopt statements made by adults as credible, given their position of authority. 76 Additionally, due to the socialisation process, it is presumed that children have a willingness to try and please adults by providing information they believe is being asked of them.77 Young children rely on the questions asked from the interviewer to provide a framework and guide them through their memory recall.78 Young children are sensitive to the differences in credibility of the source of misleading information. 79 Studies find that children are more resistant to suggestibility of 73 Robyn E Halliday, Valerie F Reyna and Brett Hayes, ‘Memory processes underlying misinformation effects in child witnesses’ (2002) 22 Developmental Review 60. 74 Ibid. 75 Ibid, 61. 76 M S Zaragoza, ‘Preschool children’s susceptibility to memory impairment’ in J Doris (ed), The suggestibility of children’s recollections: Implications for eyewitness testimony (American Psychological Association, 1991) 34. 77 P Newcombe and M Siegal, ‘Where to look first for suggestibility in young children’ (1996) 59 Cognition 348; M Siegal and C Peterson, ‘Memory and suggestibility in conversations with young children’ (1995) 47 Australian Journal of Psychology 39. 78 Sarina Butler, Julien Gross and Harlene Hayne, ‘The effects of drawing on memory performance in young children’ (1995) 31 Developmental Psychology 464. 79 Rachel Sutherland and Harlene Hayne, ‘Age-Related Changes in the Misinformation Effect’ (2001) 79(4) Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 389. 16 misinformation when presented post event from a young child compared to that of an adult. 80 Academics have also concluded that the types of adults that provide misinformation can influence the degree of suggestibility and misinformation that is adopted into a child’s memory.81 As children get older, their understanding of social roles tends to change and they can resist misleading suggestions that are presented by adults.82 While the Social Demand/Response Biases Hypothesis does provide some insight into the factors behind suggestibility, it is only tenable in some situations and is seldom the only cause behind a child adopting misleading suggestions. C Repeated Questioning The literature suggests that when questioned repeatedly on a particular point, children change their answer in an attempt to be more compatible with that of the interviewer.83 In the event of repeated questioning, the errors that are made in one interview can be carried through to subsequent interviews. 84 In these subsequent interviews, when children try and recall information, the information is erroneous, as the original memory has now been altered.85 When children are asked repeatedly about false events, the assent rate rises for each event; a child will more likely agree to a false claim in the third interview rather than the second.86 80 Stephen J Ceci, D F Ross and M P. Toglia, ‘Suggestibility in Children’s Memory: Psycholegal Implications’ (1987) 116 Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 43. 81 M J Lampinen and V L Smith, ‘The incredible (and sometimes incredulous) child witness: Child eyewitnesses’ sensitivity to source credibility cues’ (1995) 80 Journal of Applied Psychology 625; M P Toglia, D F Ross, S J Ceci and H Hembrooke, ‘The suggestibility of children’s memory; A social, psychological and cognitive interpretation’ in M L Howe, C J Brainerd and V F Reyna (eds), Development of long term retention (Springer-Verlag, 1992) 229. 82 Sutherland and Hayne, above n 79, 390. 83 S A Rose and M Blank, ‘The potency of context in children’s cognition: An illustration through conversation’ (1974) 45 Child Development 503. 84 Karen Salmon and Margret-Ellen Pipe, ‘Recalling an event one year later: The effects of props, drawing and prior interviews’ (2000) 14 Applied Cognitive Psychology 100. 85 Bruck, Ceci and Melnyk, above n 49, 193. 86 Ibid. 17 While the negative effects of repeated questioning is indisputable, some studies on repeated questioning have revealed that they can help promote further recall and make memories resistant to decay.87 Repeated questioning can enhance the strength of a memory of an event as the child is made to continuously rehearse the event – stopping the memory from fading.88 Some scholars have elaborated on this and suggest that repeated questioning can lead to hypermnesia.89 Hypermnesia refers ‘to increased recall levels associated with longer retention intervals’90 and ‘occurs when the recall of previously unreported information exceeds the forgetting of previously recalled information.’91 One of the main concerns with relying on ‘recalled’ information is the problem of whether or not this new information is genuine or created through suggestion. In relation to violent events, scholars suggest that witnesses can experience temporary retrograde and anterograde amnesia, which affects their ability to provide accurate and complete testimony directly after an event.92 What this suggests is that if in an initial interview, a child’s memory is not complete, it does not mean that the missing pieces of that memory have been permanently lost or decayed.93 87 Ibid, 190. 88 J A Quas, L C Malloy, A Melinder, G S Goodman, M D’Mello and J Schaaf, ‘Developmental differences in the effects of repeated interviews and interviewer bias on young children’s event memory and false reports’ (2007) 43 Developmental Psychology 835. 89 D La Rooy, M E Pipe and J E Murray, ‘Reminiscence and hypermnesia in children’s eyewitness memory’ (2005) 90 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 241; M L Howe, A Kelland, L Bryant-Brown and S L Clark, ‘Measuring the development of children’s amnesia and hypermnesia’ in M L Howe, C J Brainerd and V F Reyna (eds), Development of long-term retention (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1992) 77; H R Dent and G M Stephenson, ‘An experimental study of the effectiveness of different techniques of questioning child witnesses’ (1979) 18 British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 46. 90 . D G Payne, ‘Hypermnesia and reminiscence in recall: A historical and empirical review’ (1987) 10 Psychological Bulletin 15. 91 Ellen Scrivner and Martin A Safer, ‘Eyewitnesses show hypermnesia for details about a violent event’ (1988) 73(3) Journal of Applied Psychology 371. 92 S Christianson and L Nilsson, ‘Functional amnesia as induced by psychological trauma’ (1984) 12 Memory and Cognition 151; E F Loftus and T E Burns, ‘Mental shock can produce retrograde amnesia’ (1982) 10 Memory and Cognition 320. 93 Scrivner and Safer, above n 91, 372. 18 Scholars have not reached a conclusive finding on the issue of repeated questioning. While there is evidence in support, there is also a considerable body of evidence that rejects these findings. There is some discussion that the effectiveness of repeated questioning should be assessed in conjunction with the form of questioning that interviewers utilise. D Time and Type of Interviewer The timing of an interview with child witnesses is crucial for eliciting untainted, fresh memories and also as a means of protecting these memories from the effects of subsequent suggestibility.94 A higher degree of accurate information is elicited when investigative interviews occur as soon after the event as possible. 95 Interviews immediately preceding an event can restore and reinforce the strength of the original memory and inoculate it against the threat of misinformation and suggestibility. 96 Memory trace-strength theory supports this hypothesis. A memory strength trace is strong if ‘the original information is retained in an elaborate form in which many of the semantic and formal features are preserved in a richly associated network representation’97 and ‘that weaker memories are more suggestible to suggestion than strong memories.’98 Academics suggest that the earlier an interview with a child witness takes place, the more likely that the original memory will have a strong memory trace and will be less suggestible to misleading information.99 94 G S Goodman, B L Bottoms, B M Schwartz-Kenney and L Rudy, ‘Children’s testimony about a stressful event: Improving children’s reports’ (1991) 1(1) Journal of Narrative and Life History 74. 95 M B Powell and K P Roberts, ‘The effect of repeated experience on children’s suggestibility across two question types’ (2002) 16 Applied Cognitive Psychology 368. 96 K Pezdek and C Roe, ‘The effect of memory trace strength on suggestibility’ (1995) 60 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 120. 97 Ibid, 117. 98 Ibid, 120. 99 V F Reyna, R Halliday and T Marche, ‘Explaining the development of false memories’ (2002) 22 Development Review 454. 19 Other studies have suggested that it is the delay between the event and the interview that helps in memory recall as an individual has had time to consider both the original memory and misinformation which in-turn allow the misinformation to be forgotten.100 The rationale is that the interview acts as a reminder and the original memory is reactivated during the interview.101 The only pre-condition is that the interview does not occur so far outside the ‘time-window’ that it is forgotten.102 While there is evidence to suggest that delay or non-delay can have an effect on the accuracy of memory retrieval, there is no agreement among scholars that the effect of misinformation on original memories is either mitigated or exacerbated by early or late investigative interviews.103 Studies have found that the form of questions asked of child witnesses can have considerable effect on the answers given in interviews.104 As stated above, children rely on the questioning technique of the interviewer to provide a framework which helps guide them through the interview process.105 Studies suggest that children provide more accurate reports of events when asked open-ended questions as it gives a child the autonomy to recollect a specific set of events as they remember them to be,106 without suspecting that there is a predetermined answer that the interviewer is looking for.107 In 100 R A Schmidt and R A Bjork, ‘New conceptualization of practise: Common principles in three paradigms suggest new concepts for training’ (1992) 3 Psychological Science 212. 101 K P Roberts, M E Lamb and K J Sternberg, ‘Effects of the timing of post event information on preschoolers’ memories of an event’ (1999) 13 Applied Cognitive Psychology 544. 102 C Rovee-Collier, ‘Time window in cognitive development’ (1995) 31 Developmental Psychology 155. 103 For evidence on delay leading to adoption of misinformation see, T A Marche, ‘Memory strength affects reporting of misinformation’ (1999) 73 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 67; and for evidence that misinformation is adopted in interviews very soon after the event see, D S Lindsay, ‘Misleading suggestions can impair eyewitnesses’ ability to remember event details’ (1990) 16 Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition 1080. 104 H R Dent, ‘The effects of interviewing strategies on the results of interviews with child witnesses’ in A Trankell (ed), Reconstructing the past (Kluwer 1982) 283. 105 Ceci and Bruck, above n 55, 430. 106 M E Lamb, Y Orbach I Hershkowitz, P W Esplin and D Horowitz, ‘Structured forensic interview protocols improve the quality and informativeness of investigative interviews with children: A review of research using the NICHD Investigative Interview Protocol’ (2007) 31 Child Abuse & Neglect 1210. 107 C Peterson and M Biggs, ‘Interviewing children about trauma: Problems with “specific” questions’ (1997) 10 Journal of Traumatic Stress 283. 20 addition, open-ended questions require the child to contemplate all possible alternatives when answering the questions,108 while specific questions only provide a child with a predetermined set of options to choose from.109 Open-ended questions allow children to retrieve and attribute experience details to the memory, which, also assists in making children’s memories resistant to suggestibility.110 While open-ended questions have been proven to educe better memory recall, children lack the capacity to provide coherent, rich and detailed accounts of their memories purely using only open-ended questioning. 111 Compared to adults, children employ fewer memory strategies in memory retrieval and will need cues from the interviewer for their memory systems to be activated.112 It is here that academics agree that the cues provided from the interviewer can very easily become suggestive.113 One of the main problems with the use of open-ended questions is that interviewers find it difficult to implement them in the course of the interview, 114 as children can sometimes provide limited information and the specific probing is necessary to extract the requisite information.115 Specific questioning techniques can be disruptive in an interview as the child is 108 Lamb, Orbach, Hershkowitz, Esplin and Horowitz, above n 106, 1214. 109 Ibid. 110 Deborah A Connolly and Heather L Price, ‘Children’s Suggestibility for an instance of a repeated event versus a unique event: The effect of degree of association between variable details’ (2006) 93 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 208. 111 G S Goodman, J A Quas, J M Batterman-Faunce, M M Riddlesberger and J Kuhn, ‘Predictors of accurate and inaccurate memories of traumatic events experienced in childhood’ (1994) 3 Consciousness and Cognition 273. 112 D F Bjorklund, T R Coyle and J F Gaultney, ‘Developmental differences in the acquisition and maintenance of an organisational strategy: Evidence for the utilisation deficiency hypothesis’ (1992) 54 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 437. 113 Ibid. 114 Rebecca Wright and Martine B Powell, ‘Investigative interviewers’ perceptions of their difficulty in adhering to open-ended questions with child witnesses’ (2006) 8(4) International Journal of Police Science and Management 318. 115 Peterson and Biggs, above n 107, 281. 21 redirected from focusing on their own memories to focusing externally to the questions posed by the interviewer.116 1 The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Protocol Some academics have theorised that the coordinated use of both open-ended and specific questions is the preferable option when interviewing children. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Protocol (NICHD Protocol) is a program developed in the Untied States that assesses all stages of an investigative interview and the role of all the actors in the interview.117 Interviews start with introductions and rapport building in an attempt to establish a relationship with the child, and also to explain the investigative interview process.118 Open-ended prompts about the event follow in order for the child to familiarise themselves with the substantive elements of the targeted event.119 When the interviewer is confident what the child has sufficiently familiarised themselves with the target event, the interviewer will continue with open-ended questions concerning parts of the memory, followed with direct questions where necessary.120 While the NICHD Protocol has been found to promote more accurate memory recall than other interviewing techniques, it cannot address the motivational factors behind a child’s reluctance to disclose information about an event.121 Further, the literature is slim on how the NICHD Protocol is tailored for those with mental and intellectual difficulties.122 116 M B Powell, R P Fisher and R Wright, ‘Investigative Interviewing’ in N Brewer and K Williams (eds), Psychology and Law: An Empirical Perspective (Guilford Press, 2005) 25. 117 Lamb, Orbach, Hershkowitz, Esplin and Horowitz, above n 106, 1204. 118 Ibid. 119 Ibid, 1205. 120 Ibid. 121 M E Pipe, M E Lamb, Y Orbach and A Cederborg, Child Sexual Abuse: Disclosure, delay and denial (Routledge, 2007) 52. 122 P M Sullivan and J F Knutson, ‘Maltreatment and Disabilities: A population-based epidemiological study’ (2000) 24(10) Child Abuse and Neglect 1268. 22 Therefore, while there is promise in the research on the effective interviewing techniques of children, there is still more work that needs to be done with relation to all the competing variables and how they work together to elicit the most accurate information out of child witnesses. V THE EASTWOOD AND PATTON REPORT The issues discussed above are further aggravated when children move into the court proceedings themselves. Not only is the misleading, deceptive and suggestive nature of the trial damaging for children, it can have a devastating effect on their memories. The Eastwood and Patton Report was produced by Dr Christine Eastwood and Professor Wendy Patton, which assessed the criminal justice system’s response to child complainants of sexual abuse. One of the significant issues faced by child witnesses is the lack of protection offered by actors of the court system before, during or after the court process.123 One defence lawyer stated; The Crown don't care about the child. The police don't care about the child. And I don't care about the child. You see the trial is not about the child. It simply makes the child a witness… You've got to get around this idea that the criminal justice system is about the child, it shouldn't be about the child, and hopefully will never be about the child.124 The Eastwood and Patton Report conducts a cross-jurisdictional analysis of Queensland (Qld), New South Wales (NSW) and Western Australia (WA) to determine how the states manage child witnesses and facilitate a process where the child can provide their evidence in a safe and neutral environment. Out of the three states evaluated, it was found that WA ranked the best, with Qld ranked the lowest. 125 One of the key differentials that separated WA from the other states was the commitment to the 123 Sarah O’Neill and Rachel Zajac, ‘The role of repeated interviewing in children’s responses to cross examination style questioning’ (2013) 104(1) British Journal of Psychology 24. 124 Eastwood and Patton, above n 4, 2. 125 Ibid, 11-32. 23 protection of children during the court process both in terms of legislation126 and legal reform.127 The Attorney-General, in the Second Reading Speech of the Criminal Law (Procedure) Amendment Bill128 was aware of the harm that the trial process have for children and the authenticity of their memories, ‘the delays caused by preliminary hearings also have severe repercussions as they can impact upon the ability of witnesses to recall facts as clearly as they once might have.’129 Throughout their research, Eastwood and Patton with a host of other scholars have found that the criminal justice system itself is responsible for causing further trauma and abuse to child witnesses.130 The traditional criminal justice system was developed for adult use and leaves children painfully vulnerable to its effects. The Eastwood and Patton Report evaluated, from the child’s perspective, the various stages of the trial process from committal hearings all the way to the final verdict and sentence.131 One of the most detrimental effects of the court process is through cross-examination. Lawyers use crossexamination as a means of discrediting the witness through misleading, suggestive and deceptive means.132 This is particularly more problematic in the case of children taking the stand. The following extract of a court transcript demonstrates the degree of forced suggestibility in children: Mr X: Did he ever threaten you? Child: I don't think so. 126 Evidence Act 1906 (WA) s 106. 127 Law Reform Commission of Western Australia, Evidence of Children and Other Vulnerable Witnesses, Project No 87 (1991). 128 Criminal Law (Procedure) Amendment Bill 2002 (WA). 129 Western Australia, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 27 March 2002, 9026-9030 (James Andrew McGinty, Attorney-General). 130 E Henderson, ‘Persuading and controlling: The theory of cross examination in relation to children’ in H Westcott, G Davies and R Bull (eds), Children’s Testimony: A handbook of psychological research and forensic practise (John Wiley & Sons, 2002) 285; C Smart, Feminism and the power of the law (Routledge, 1989) 24. 131 Eastwood and Patton, above n 4, 49-62. 132 Henderson, above n 130, 200. 24 Mr X: What do you mean you don't think so? Child: I can’t remember. Mr X: So the answer is that he never threated you. Is that right? Child: Yes.133 Comments made by children in the Eastwood and Patton Report about being crossexamined, highlight the judicially sanctioned contamination of children’s memories by lawyers and actors of the court. Children from Qld stated how the defence council would badger and ask compound questions in the hope of confusing them; ‘he asked lots of difficult questions and tried to mess me up.’134 A child from NSW expressed how, ‘He [defence council] was trying to get me to say all this stuff [that] wasn't true.’135 Another child documented how the stress of the trial forced them to answer questions as quickly as possible just so they could leave.136 In WA, even with the facilities available, one child reported: I think he [defence council] was trying to confuse me – and that’s awful because in my mind I’m just trying to have my story out there and just to get it out. And then I’ve got some guy twisting my words and saying no, no, no.137 Aside from the suggestibility that a child may be subject to during the investigative interview stage prior to the trial, the above extract and comments is a clear and example of the sanctioned contamination of a child’s memory at a highly stressful and critical time. While the Eastwood and Patton Report did not focus on the suggestibility of child witnesses exclusively, it does indicate that the issue of suggestibility is never far from any evaluation of children and their participation in the judicial system. 133 Eastwood and Patton, above n 4, 134 Eastwood and Patton, above n 4, 59 135 Eastwood and Patton, above n 4, 60 136 Ibid 137 Eastwood and Patton, above n 4, 4. 25 VI THE INNOCENCE PROJECT While this paper has evaluated the problems with child witnesses and their evidence, this section will go one step further and demonstrate the devastating effect of not having adequate interviewing techniques in place during the investigation period and how that can result in innocent people being sent to prison for crimes they did not commit. The Innocence Project is a not-for-profit legal organisation in the United States, dedicated to the exoneration of wrongfully convicted individuals.138 The use of DNA testing has given those who are wrongfully accused a second chance for release and those who are truly guilty to be bought to justice. The Innocence Project also works with law enforcement, law and journalism schools, and lobbies for criminal law reform to prevent further injustices in the future.139 One of the main features of the Innocence Project is the research and training that is offered for law enforcement officials about the suggestibility of human memory, and techniques that can be utilised to ensure the most accurate recall. Studies conducted have found that close to 75% of wrongful convictions are due to eyewitness misidentification – contributable to ineffective interviewing techniques, problematic line-ups and other identification procedures.140 Some of the techniques identified to assist in more accurate recall are the utilisation of double blind administration, proper line-up composition, recording the procedure, adequate instructions for the witness, control of confidence statements and sequential representation.141 While these techniques are being used now in the facilitation of witness investigation, one case in particular bought to the fore the impact of inadequate interviewing techniques and insufficient investigative procedures. 138 Benjamin N Cardozo School of Law, Yeshiva University, <http://www.innocenceproject.org> the Faces of Exoneration, 139 Ibid. 140 Ibid 141 Benjamin N Cardozo School of Law, Yeshiva University, Understand the Causes Eyewitness Misidentification, <http://www.innocenceproject.org/understand/Eyewitness-Misidentification.php> 26 This particular case tells the story of Ronald Cotton, a man wrongfully convicted of a crime he did not commit. A Ronald Cotton or Bobby Poole? In 1984, an assailant entered Jennifer Thompson’s home where he robbed and raped her.142 During the assault, Ms Thompson made every effort to familiarise herself with her assailant; how tall he was, if he had any tattoos and whether or not he had any unusual jewellery.143 Later on that same night, another woman was also assaulted in the same manner as Ms Thompson. Authorities were provided with leads from different people of the public, claiming to know whom the offender was, namely one, Ronald Cotton (Cotton).144 Cotton heard of some of the claims being made against him and went to the police station in an attempt to make sense of the allegations.145 The police then arranged a photo array for Ms Thompson, with a photo of Cotton included, in which she positively identified Cotton as her assailant.146 The authorities organised for a line-up, in which Ms Thompson positively identified Cotton once again.147 Cotton was charged and in 1985 was convicted of one count of burglary and one count of rape and was sentenced to life imprisonment.148 While in prison, Cotton had heard another inmate, Bobby Poole, bragging how it was he who had raped Jennifer Thompson and the other victim.149 Cotton was subsequently 142 State v Cotton, 351 S.E.2.d 277, 280 (N.C., 1987). 143 Steve J Joffee, ‘Long overdue: Utah’s incomplete approach to eyewitness identification and suggestions for reform’ (2010) Utah Law Review 443. 144 Richard A Wise, Clifford S Fishman and Martin A Safer, ‘How to analyse the accuracy of eyewitness testimony in a criminal case’ (2009) 42(2) Connecticut Law Review 439. 145 Ibid, 440. 146 Noah Clements, ‘Flipping a coin: A solution for the inherent unreliability of eyewitness identification testimony’ (2007) 40 Indiana Law Review 276. 147 Gary L Wells, ‘Eyewitness Identification: Systemic Reforms’ (2006) Wisconsin Law Review 622. 148 Wise, Fishman and Safer, above n 1144, 438. 149 Ibid. 27 granted a re-trial given the second victim had failed to identify Cotton in a line-up.150 During the trial, the second victim decided that Cotton was in fact the man who had raped her, even though she had never identified him in a line-up.151 Ms Thompson and the second victim both confirmed hat Cotton was the man who had raped them.152 Further, the court excluded evidence that Bobby Poole had confessed to the crimes.153 Cotton was found guilty of both offences and was sentenced by the Alamance County Superior Court to prison for life plus fifty-four years.154 It was not until 1995, that through the use of DNA analysis, Cotton was exonerated from prison and all charges against him were dropped.155 While this story does have a happy ending with an innocent man being released, and the true offender being bought to justice, the fact cannot be dismissed that the same innocent man was made to spend more then a decade in prison for a crime he did not commit. What this story demonstrates is the tragic consequences of the inadequate handling of eyewitness testimony. Even though Ms Thompson was sure that the person she identified was her assailant, Cotton and Bobby Poole were still two different men. This story shows the fallibility of human memory and highlights how more effective measures need to be implemented in order to stop this from happening again. VII CONCLUSION In conclusion, this paper has looked at some of the issues that impact the accurate recall of memories in child witnesses. Studies, as exhibited above, demonstrate that memories are incredibly malleable and subject to many forms of distortions. Types of memories 150 State v Cotton, 351 S.E.2.d 277, 280 (N.C., 1987). 151 Wise, Fishman and Safer, above n 144, 439. 152 Steven E Clark, ‘Costs and benefits of eyewitness identification reform psychological science and public policy’ (2012) 7(3) Perspectives on Psychological Science 247. 153 Wise, Fishman and Safer, above n 144, 439. 154 State v Cotton, 351 S.E.2.d 277, 280 (N.C., 1987). 155 Neil Vidmar, James E Coleman Jnr and Theresa A Newman, ‘Rethinking reliance on eyewitness testimony’ (2010) 94(1) Judicature 16. 28 such as repressed, suppressed, altered and false memories, while still the subject of some academic debate, warrant concern. Their existence impacts the veracity of children’s evidence and the probative value of that evidence in the eyes of judges and juries. A child’s level of suggestibility and the damaging effects of confirmation and interviewer bias is a devastating combination that has the potential to exacerbate damage to the integrity of a child’s memory. The NICHD protocol provides guidelines for law enforcement officials and clinicians alike for more effective interviewing techniques with relation to children, in order to elicit the most information-rich and uncontaminated memories. While this is a positive step in the right direction, further studies need to be conducted in order to develop a conclusive and effective interviewing strategy for children. This paper also evaluated the Eastwood and Patton Report for its insight into the inadequate and often ineffective treatment of children as witnesses in sexual abuse cases. The findings suggest the treatment of children as witnesses is not only inappropriate but can have negative implications on a child’s ability to categorically recount their testimony. Finally this paper assessed what would happen if the worst came to fruition – namely that somebody’s eyewitness testimony would result in an innocent person being sent to prison. While the evaluation of the Innocence Project did not exclusively focus on child witnesses, it demonstrates the issues with eyewitness testimony and its reliability irrespective of age. The issues and concerns about child witnesses will not go away as children are getting more involved in legal processes than ever before. There is no denying the positive steps that scholars and clinicians have taken in an attempt to understand the complexity of children’s memory. More work needs to be undertaken to ensure that the memories of children are not subsequently tampered with through voluntary or involuntary adult influence and are as reliable as they can be when in a court. 29 VIII REFERENCE LIST A Journal Articles Aarons, N M, M B Powell and J Browne, ‘Police perceptions of interviews involving children with intellectual disabilities: A qualitative inquiry’ (2004) 14(3) Policing and Society 269 Anderson, M C, R Bjork and E Bjork, ‘Remembering can cause forgetting: Retrieval dynamics in long term memory’ (1994) 20(5) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition 1063 Anderson, M C and B A Spellman, ‘On the status of inhibitory mechanisms in cognition: Memory retrieval as a model case’ (1995) 102 Psychological Review 68 Anderson, M C and C Green, ‘Suppressing unwanted memories by executive control’ (2001) 410 Nature 366 Bjorklund, D F, T R Coyle and J F Gaultney, ‘Developmental differences in the acquisition and maintenance of an organisational strategy: Evidence for the utilisation deficiency hypothesis’ (1992) 54 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 434 Bones, K S and P Farvolden, ‘Revisiting a century-old Freudian slip – From suggestion disavowed to the truth repressed’ (1996) 119(3) Psychological Bulletin 355 Brainerd, C J, ‘Three-state models of memory development: A review of advances in statistical methodology’ (1985) 40 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 375 Brainerd, C J, V F Reyna and E Brandse, ‘Are Children’s False Memories more persistent than their True Memories?’ (1995) 6 Psychological Science 359 Brewin, C R and B Andrews, ‘Recovered Memories of Trauma: Phenomenology and Cognitive Mechanisms’ (1998) 18(8) Clinical Psychology Review 949 30 Brewin, Chris R and Bernice Andrews, ‘Why it is Scientifically Respectable to Believe in Repression: A Response to Patihis, Ho, Tingen, Lilienfeld and Loftus (2014)’ (2014) Psychological Science 1965 Brown, A L, ‘Theories of memory and the problem of development: Activity, growth and knowledge’ (1979) Levels of Processing 225 Bruck, Maggie and Stephen J Ceci, ‘The Suggestibility of Children’s Memory’ (1990) 50 Annual Review of Psychology 419 Bruck, Maggie, Stephen J Ceci and Laura Melnyk, ‘Draw it Again Sam: The Effects of Drawing on Children’s Suggestibility and Source Monitoring Ability’ (2000) 77(3) Journal of Experimental Psychology 169 Butler, Sarina, Julien Gross and Harlene Hayne, ‘The effects of drawing on memory performance in young children’ (1995) 31 Developmental Psychology 460 Cassel, W S, C E M Roebers and D F Bjorklund, ‘Developmental patterns of eyewitness responses to repeated and increasingly suggestive questions’ (1998) 61 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 116 Ceci, Stephen J, D F Ross and M P Toglia, ‘Suggestibility in Children’s Memory: Psycholegal Implications’ (1987) 116 Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 38 Christianson S and L Nilsson, ‘Functional amnesia as induced by psychological trauma’ (1984) 12 Memory and Cognition 142. Clark, Steven E, ‘Costs and benefits of eyewitness identification reform psychological science and public policy’ (2012) 7(3) Perspectives on Psychological Science 238 Clements, Noah, ‘Flipping a coin: A solution for the inherent unreliability of eyewitness identification testimony’ (2007) 40 Indiana Law Review 271 31 Connolly, Deborah A and Heather L Price, ‘Children’s Suggestibility for an instance of a repeated event versus a unique event: The effect of degree of association between variable details’ (2006) 93 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 207 Dent, H R and G M Stephenson, ‘An experimental study of the effectiveness of different techniques of questioning child witnesses’ (1979) 18 British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 41 Garrioch, L and C Brimacombe, ‘Lineup administrator’s expectations: their impact on eyewitness confidence’ (2001) 25 Law and Human Behaviour 299 Goodman, G S, ‘Children’s testimony in historical perspective’ (1984) 40 Journal of Social Issues 9 Goodman, G S, B L Bottoms, B M Schwartz-Kenney and L Rudy, ‘Children’s testimony about a stressful event: Improving children’s reports’ (1991) 1(1) Journal of Narrative and Life History 69 Goodman, G S, J A Quas, J M Batterman-Faunce, M M Riddlesberger and J Kuhn, ‘Predictors of accurate and inaccurate memories of traumatic events experienced in childhood’ (1994) 3 Consciousness and Cognition 269 Goodman, Gail S, Anupama Sharma, Sherry F Thomas and Mary G Considine, ‘Mother knows best: Effects of relationship status and interviewer bias on children’s memory’ (1995) 60 Journal of Experimental Psychology 195 Halliday, Robyn E, Valerie F Reyna and Brett K Hayes, ‘ Memory processes underlying misinformation effects in child witnesses’ (2002) 22 Developmental Review 37 Holmes, David S, ‘The Evidence for Repression: An examination of sixty years of research’ in J L Singer (eds), Repression and Dissociation: Implications for Personality theory, Psychopathology and Health (University of Chicago Press, 1990) 85 32 Hughes-Scholes, Carolyn H and Martine B Powell, ‘An examination of the types of leading questions used by investigative interviewers of children’ (2008) 31(2) Policing (Bradford): An International Journal of Police Strategies 210 Joffee, Steve J, ‘Long overdue: Utah’s incomplete approach to eyewitness identification and suggestions for reform’ (2010) Utah Law Review 443 Khurshid, Ayesha and Kristine M Jacquin, ‘Expert Testimony Influences Juror Decisions in Criminal Trials Involving Recovered Memories of Childhood Sexual Abuse’ (2013) 22(8) Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 949 Kilstrom, John F, ‘An Unbalanced Balancing Act: Blocked, Recovered and False Memories in the Laboratory and Clinic [review and commentaries] (2004) 11 Clinical Psychology: Science and Practise 34 Kanvovitz, Jaqueline, ‘Hypnotic Memories and Civil Sexual Abuse Trials’ (1992) 45 Vanderbilt Law Review 1185 Koriat, A and M Goldsmith, ‘Memory metaphors and the real-life/laboratory controversy: Correspondence versus storehouse conceptions of memory (1996) 19 Behavioral and Brain Sciences 167 La Rooy, D, M E Pipe and J E Murray, ‘Reminiscence and hypermnesia in children’s eyewitness memory’ (2005) 90 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 235 Joyce, W Lacy and Craig E L Stark, ‘The Neuroscience of Memory: Implications for the Courtroom’ (2013) 14 Nature Reviews 649 Lampinen, M J and V L Smith, ‘The incredible (and sometimes incredulous) child witness: Child eyewitnesses’ sensitivity to source credibility cues’ (1995) 80 Journal of Applied Psychology 621 Lamb, M E, Y Orbach I Hershkowitz, P W Esplin and D Horowitz, ‘Structured forensic interview protocols improve the quality and informativeness of investigative interviews 33 with children: A review of research using the NICHD Investigative Interview Protocol’ (2007) 31 Child Abuse & Neglect 1201 Laney, Cara and Elizabeth F Loftus, ‘Recent Advances in False Memory Research’ (2013) 43(2) South African Journal of Psychology 137 Lindsay, D S, ‘Misleading suggestions can impair eyewitnesses’ ability to remember event details’ (1990) 16 Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition 1077 Loftus, E F and T E Burns, ‘Mental shock can produce retrograde amnesia’ (1982) 10 Memory and Cognition 318 Loftus, Elizabeth F, ‘The reality of repressed memories’ (1993) 48(5) American Psychologist 518 Loftus, Elizabeth F, ‘Our Changeable Memories: Legal and Practical Implications’ (2003) 4 Nature Reviews Neuroscience 231 Loftus, Elizabeth F, ‘Planting misinformation in the human mind: a 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory’ (2005) 12(4) Learning & Memory 361 Lord, C G, L Ross and M R Lepper, ‘Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: the effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence’ (1979) 37(11) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2098 Luus, C and G Wells, ‘The malleability of eyewitness confidence: co-witness and perseverance effects’ (1994) 79, Journal of Applied Psychology 714 Marche, T A, ‘Memory strength affects reporting of misinformation’ (1999) 73 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 45 Marin, B V, D L Holmes, M Guth and P Kovac, ‘The potential of children as eyewitnesses: A comparison of children and adults on eyewitness tasks’ (1995) 3 Law and Human Behavior 510 34 Mayr, U and S W Keele, ‘Changing the internal constraints on action: the role of backward inhibition’ (2000) 129 Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 4 McAuliff, Bradley D and Brian H Bornstein, ‘Beliefs and expectancies in legal decision making: an introduction to the Special Issue’ (2012) 18(1) Psychology, Law and Crime 1 McCauley, M R and R P Fisher, ‘Facilitating children’s eyewitness recall with the revised cognitive interview’ (1995) 80 Journal of Applied Psychology 510 McNally, Richard J and Elke Geraerts, ‘A New Solution to the Recovered Memory Debate’ (2009) 4 Perspectives on Psychological Science 126 McWilliams, Kelly, Rachel Narr, Gail S. Goodman, Sandra Ruiz and Macaria Mendoza, ‘Children’s memory of their mother’s murder: Accuracy, suggestibility, and resistance to suggestion’ (2013) 21(5) Memory 591 Newcombe, P and M Siegal, ‘Where to look first for suggestibility in young children’ (1996) 59 Cognition 337 Nickerson, R S, ‘Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises’ (1998) 2 Review of General Psychology 175 O’Neill, Sarah and Rachel Zajac, ‘The role of repeated interviewing in children’s responses to cross examination style questioning’ (2013) 104(1) British Journal of Psychology 14 Ost, James, Dan B Wright, Simon Easton, Lorraine Hope and Christopher C French, ‘Recovered memories, Satanic abuse, Dissociative Identity Disorder and false memories in the UK: A Survey of Clinical Psychologists and Hypnotherapists’ (2013) 19(1) Psychology, Crime and Law 1 Payne, D G, ‘Hypermnesia and reminiscence in recall: A historical and empirical review’ (1987) 10 Psychological Bulletin 5 35 Patihis, Lawrence, Lavina Y Ho, Ian W Tingen, Scott O Lilienfeld and Elizabeth F. Loftus, ‘Are the “Memory Wars” Over? A Scientist – Practitioner Gap in Beliefs about Repressed Memory’ (2014) 25(2) Psychological Science 519 Patihis, Lawrence, Scott O Lilenfeld, Lavina Y Ho and Elizabeth F Loftus, ‘Unconscious repressed memory is scientifically questionable’ (2014) Psychological Science 1967 Peterson, C and M Biggs, ‘Interviewing children about trauma: Problems with “specific” questions’ (1997) 10 Journal of Traumatic Stress 279 Peterson, C, ‘Children’s memory for medical emergencies: 2 years later’ (1999) 35 Developmental Psychology 1493 Pezdek, Kathy and Danielle Hodge, ‘Planting False Childhood Memories in Children: the Role of Event Plausibility’ (1999) 70 Child Development 887 Pezdek, K and C Roe, ‘The effect of memory trace strength on suggestibility’ (1995) 60 Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 116 Powell, M B and K P Roberts, ‘The effect of repeated experience on children’s suggestibility across two question types’ (2002) 16 Applied Cognitive Psychology 367 Powell, Martine B, Rebecca Wright and Carolyn H Hughes-Scholes, ‘Contrasting the perceptions of child testimony experts, prosecutors and police officers regarding individual child abuse interviews’ (2010) 11(3) Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 33 Powell, Martine B, Carolyn N Hughes-Scholes and Stefanie J Sharman, ‘Skill in interviewing reduces confirmation bias’ (2012) 9 Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling 126 Quas, J A, L C Malloy, A Melinder, G S Goodman, M D’Mello and J Schaaf, ‘Developmental differences in the effects of repeated interviews and interviewer bias on young children’s event memory and false reports’ (2007) 43 Developmental Psychology 823 36 Rapus, Tanya Benton, David F Ross, Emily Bradshaw, W Neil Thomas and Gregory Bradshaw, ‘Eyewitness Memory is still not Common Sense: Comparing Jurors, Judges and Law Enforcement to Eyewitness Experts’ (2006) 20(1) Applied Cognitive Psychology 117 Reyna, V F, R Halliday and T Marche, ‘Explaining the development of false memories’ (2002) 22 Development Review 436 Roberts, Kim P and Martine B Powell, ‘The roles of prior experience and the timing of misinformation presentations on young children’s event memories’ (2007) 78(4) Child Development 1137 Roberts, K P, M E Lamb and K J Sternberg, ‘Effects of the timing of post event information on preschoolers’ memories of an event’ (1999) 13 Applied Cognitive Psychology 541 Roediger, III H L, ‘Memory illusions’ (1996) 35 Journal of Memory and Language 76 Rose, S A and M Blank, ‘The potency of context in children’s cognition: An illustration through conversation’ (1974) 45 Child Development 499 Rovee-Collier, C, ‘Time windows in cognitive development’ (1995) 31 Developmental Psychology 147. Salmon, Karen and Margret-Ellen Pipe, ‘Recalling an event one year later: The effects of props, drawing and prior interviews’ (2000) 14 Applied Cognitive Psychology 99 Saywitz, Karen and Rebecca Nathanson, ‘Children’s testimony and their perceptions of stress in and out of the courtroom’ (1993) 71 Child Abuse and Neglect 613 Schmidt, R A and R A Bjork, ‘New conceptualization of practise: Common principles in three paradigms suggest new concepts for training’ (1992) 3 Psychological Science 207 Scrivner, Ellen and Martin A Safer, ‘Eyewitnesses show hypermnesia for details about a violent event’ (1988) 73(3) Journal of Applied Psychology 371 37 Semmler, C, N Brewer and G Wells, ‘Effects of post-identification feedback on eyewitness identification and non-identification confidence’ (2004) 89, Journal of Applied Psychology 334 Siegal, M and C Peterson, ‘Memory and suggestibility in conversations with young children’ (1995) 47 Australian Journal of Psychology 38 Strange, Deryn, Mathew P Gerrie and Maryanne Garry, ‘A Few Seemingly Harmless Routes to a False Memory’ (2005) 6 Cognitive Processes 237 Sullivan, P M and J F Knutson, ‘Maltreatment and Disabilities: A population-based epidemiological study’ (2000) 24(10) Child Abuse and Neglect 1257 Sutherland, Rachel and Harlene Hayne, ‘Age-Related Changes in the Misinformation Effect’ (2001) 79(4) Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 388 Thompson, William C, Alison K Clarke-Stewart and Stephen J Lapore, ‘What did the Janitor do? Suggestive interviewing and the accuracy of children’s accounts’ (1997) 21 Law and Human Behavior 405 Vidmar, Neil, James E Coleman Jnr and Theresa A Newman, ‘Rethinking reliance on eyewitness testimony’ (2010) 94(1) Judicature 16 Wells, Gary L, ‘Eyewitness Identification: Systemic Reforms’ (2006) Wisconsin Law Review 615 Whipple, Guy, ‘The observer as reporter: a survey of the “psychology of testimony”’ (1909) 6 Psychological Bulletin 153 Wise, Richard A, Clifford S Fishman and Martin A Safer, ‘How to analyse the accuracy of eyewitness testimony in a criminal case’ (2009) 42(2) Connecticut Law Review 435 Wright, Rebecca and Martine B Powell, ‘Investigative interviewers’ perceptions of their difficulty in adhering to open-ended questions with child witnesses’ (2006) 8(4) International Journal of Police Science and Management 316 38 B Edited Chapters Anderson, M C and E Huddleston, ‘Towards a cognitive and neurobiological model of motivating forgetting’ in R F Belli (eds), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol 58. True and false recovered memories: Towards a reconciliation of the debate (New York, NY: Springer, 2012) 53 Ceci, Stephen J and Maggie Bruck, ‘The role of interviewer bias’ in Stephen J Ceci and Maggie Bruck, Jeopardy in the courtroom: A scientific analysis of children’s testimony (American Psychological Association, 1999) 87 Courage, M L and M L Howe, ‘Autobiographical memory: Individual differences and developmental course’ in A Gruszka, G Matthews and B Szymura (eds), Handbook of Individual Differences in Cognition (New York NY: Springer, 2010) 403 Dent, H R, ‘The effects of interviewing strategies on the results of interviews with child witnesses’ in A Trankell (ed), Reconstructing the past (The Netherlands: Kluwer 1982) 279 Goodman, G S, L Rudy, B L Bottoms and C Aman, ‘Children’s concerns and memory functioning: Conclusions from a longitudinal study of family violence’ in M Howe, G S Goodman and D Cicchetti (eds), Stress, Trauma and Children’s Memory Development: Neurobiological, Cognitive, Clinical and Legal Perspectives (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1990) 249 Henderson, E, ‘Persuading and controlling: The theory of cross examination in relation to children’ in H Westcott, G Davies and R Bull (eds), Children’s Testimony: A handbook of psychological research and forensic practise (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2002) 279 Howe, M L, A Kelland, L Bryant-Brown and S L Clark, ‘Measuring the development of children’s amnesia and hypermnesia’ in M L Howe, C J Brainerd and V F Reyna (eds), Development of long-term retention (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1992) 56 39 Johnson, Marcia K, Carol L Raye, Karen J Mitchell and Elizabeth Ankudowich, ‘ The Cognitive Neuroscience of True and False Memories’ Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol 58. True and false recovered memories: Towards a reconciliation of the debate (New York, NY: Springer, 2012) 15 Powell, M B, R P Fisher and R Wright, ‘Investigative Interviewing’ in N Brewer and K Williams (eds), Psychology and Law: An Empirical Perspective (New York: Guilford Press, 2005) 11 Powell, M B, M Garry and N D Brewer, ‘Eyewitness Testimony’ in I Frekelton and H Selby (eds) Expert Evidence (Sydney NSW: Thompson Reuters, 2009) 1 Rose, N J and J W Sherman, ‘Expectancy’ in A W Kruglanski and E T Higgins (eds), Social Psychology: Handbook of basic principles (New York: Guilford Press, 2007) 91 Schneider, N and F E Weinert, ‘Universal Trends and Individual Differences in Memory Development’ in A de Ribaupierre (eds), Transition Mechanisms in Child Development: The Longitudinal Perspective (Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press) 68 Schneider, W and D F Bjorklund, ‘Memory’ in W Damon, D Kuhn, and R S Siegler (eds), Handbook of child psychology: Cognition, perception and language (New York: Wiley, 1998) 467 Schneider W and M Pressley, Memory development between 2 and 20 (Springer New York, 2nd ed, 1989) Toglia, M P, D F Ross, S J Ceci and H Hembrooke, ‘The suggestibility of children’s memory; A social, psychological and cognitive interpretation’ in M L Howe, C J Brainerd and V F Reyna (eds), Development of long term retention (New York: SpringerVerlag, 1992) 217 Zaragoza, M S, ‘Preschool children’s susceptibility to memory impairment’ in J Doris (ed), The suggestibility of children’s recollections: Implications for eyewitness testimony (Washington DC: American Psychological Association, 1991) 27 40 C Books Loftus, Elizabeth F, Eyewitness Testimony (Harvard University Press, 2nd ed, 1996) Pipe, M E, M E Lamb, Y Orbach and A Cederborg, Child Sexual Abuse: Disclosure, delay and denial (Routledge, 2007) Smart, C, Feminism and the power of the law (London: Routledge, 1989) D Cases State v Cotton, 351 S.E.2.d 277, 280 (N.C., 1987) E Legislation Criminal Law (Procedure) Amendment Bill 2002 (WA) Evidence Act 1906 (WA) F Other Benjamin N Cardozo School of Law, Yeshiva University, the Faces of Exoneration, <http://www.innocenceproject.org> Eastwood C, and W Patton, ‘The experiences of child complainants of sexual abuse in the criminal justice system’ (2002) Report to the Criminology Research Council, Canberra. Western Australia, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 27 March 2002, 90269030 (James Andrew McGinty, Attorney-General) Law Reform Commission of Western Australia, Evidence of Children and Other Vulnerable Witnesses, Project No 87 (1991) 41