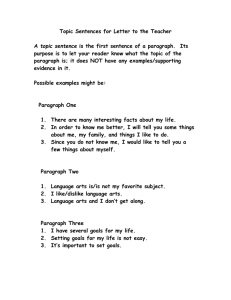

Think Literacy writing strategies

advertisement