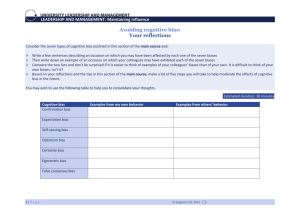

Cognitive Bias Report

advertisement