Week 5 - Relevance

advertisement

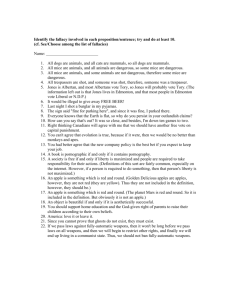

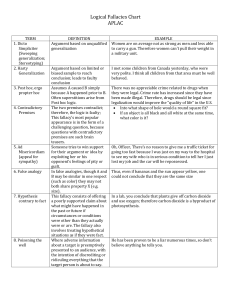

5. Relevance 1 Relevance “Relevance,” you’ll recall is the second of Govier’s ARG conditions. So, no surprise, it is important to understand the idea of relevance in order to evaluate arguments. As Govier notes (172), however, the idea of relevance is so basic to thinking and the development of knowledge that it is difficult to define. Still, there are some things that we can usefully say about it … 2 1 Understanding Relevance Govier distinguishes three basic ideas about relevance: 1. Positive Relevance 2. Negative Relevance 3. Irrelevance 3 Positive Relevance Statement A is positively relevant to another statement B if and only if the truth of A counts in favour of the truth of B. I.e., A provides some evidence for B, or some reason to believe that B is true. Condition: If A is true (acceptable), then A supplies some evidence or support for B. 4 2 Example 1. University graduates have, on average, much higher salaries than people who don’t go to university. 2. University graduates are more likely to be promoted. 3. University graduates are more likely to end up in professional and managerial positions. 4. Getting a university education is a good way for an individual to build a better economic future. 1, 2, and 3, are all positively relevant to 4. 5 Negative Relevance Statement A is negatively relevant to another statement B if and only if the truth of A counts against the truth of B. 6 3 Example 1. Experts attribute a marked rise in childhood obesity and adult onset diabetes to our increased consumption of fast food. 2. Fast food can be part of a healthy diet. 1 is negatively relevant to 2. 7 Irrelevance Statement A is irrelevant to another statement B is and only if it is neither positively relevant nor negatively relevant to B. When there is irrelevance, there is no relationship of logical support or logical undermining between the two statements. A does not provide a reason for B; nor does it provide a reason against B. 8 4 (Classic) Example 1. It’s new! 2. It’s improved! The truth of 1 is irrelevant to the truth of 2. 9 Example (Govier’s) 1. Natural catastrophes such as earthquakes are beyond human control. 2. Human beings have no freedom of choice concerning their actions. 1 is irrelevant to 2; the fact that some things are beyond our control says nothing about things that are under our control. 10 5 Relevance and the ARG Conditions If the premises of an argument considered together are irrelevant or negatively relevant to the conclusion, then that argument is not cogent. And, any time the premises of an argument fail the R condition, the argument as whole fails the G condition as well—irrelevant or negatively relevant premises cannot provide adequate grounds for any conclusion. 11 Premises that seem to be irrelevant Govier notes that sometimes premises which seem to be irrelevant can be made relevant if we assume one or more missing premises. 12 6 Govier’s Example 1. Both our [Western] type of alphabet and our type of numbers originate from the Middle East. So, 2. Western civilization as a distinct entity does not exist. At first glance, 1 appears to be entirely irrelevant to 2, but can make it relevant by supplying some missing premises that the arguer may have intended … 13 1. Both our [Western] type of alphabet and out type of numbers originate from the Middle East. 3. The Middle East is not part of the West. 4. A civilization is a distinct entity only if all of its important elements come from within its own area. So, 2. Western civilization as a distinct entity does not exist. 3 and 4 make 1 relevant to 2, but only introducing some possibly unacceptable premises; the argument no longer fails R, but it may fail A. 14 7 Another (Simpler) Example 1. Sheryl has brown eyes Therefore, 2. Sheryl is a good hockey player. 1. Sheryl has brown eyes 3. People with brown eyes are good hockey players Therefore, 2. Sheryl is a good hockey player. By adding 3., we can make 1. relevant to 2., but only at the cost of introducing an premise of doubtful acceptability. 15 “Expansive Reconstruction” Some informal logicians maintain that it is (sometimes) acceptable to supply a missing premise in order to overcome R problems (Recall: the “principle of charity”) Govier cautions. however: 1) Can we be sure that we are reconstructing the argument and not supplying a new argument? 2) We may simply shift the problem from one ARG condition to another (as in the previous examples). 16 8 Non Sequiturs Non sequitur < Latin “does not follow” An irrelevant premise or any remark that seems irrelevant or out of context. (Reportive definition context: generally, simply a mistake, not something that an arguer does consciously). 17 Red Herring A distracting remark that is irrelevant to the argument and leads an audience away from the point at issue. (Reportive definition context: sometimes simply a mistake, sometimes a strategy consciously in order to persuade). 18 9 Example: A dialogue A. Why are you not willing to support gun control legislation? Don’t you have any feelings for the thousands of lives that are lost each year do to gun violence? B. I don’t understand why people who get so worked up people being killed by guns don’t have the same feelings for the thousands of unborn children whose lives are blotted out each year. Isn’t the sanctity of life involved in both issues? Why haven’t you supported our anti-abortion legislation? 19 Fallacies of Relevance We’ve already encountered a few fallacies (common mistakes in reasoning, of a sort that people tend not to notice) in connection with ambiguity and vagueness. (equivocation, begging the question) Govier now introduces several more: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. The Straw Man Fallacy The Ad Hominem Fallacy Guilt by Association Fallacious appeals to Popularity Fallacious appeals to Ignorance 20 10 The Straw Man Fallacy The straw man (or woman) fallacy is committed when a person misrepresents an argument, theory or claim, and then, on the basis of the misrepresentation, claims to have refuted the position that he has misrepresented. 21 Example: A dialogue You say: “Christmas has become overcommercialized and depressing” I say: “Why do you want to do away with Christmas! It makes kids happy. It stimulates the economy. Moreover, it is one of our great Christian traditions and we must maintain our traditions or society will crumble” 22 11 Avoiding the Straw Man in Evaluating Arguments The straw man fallacy involves misrepresenting someone else’s position, so perhaps the most straightforward way to avoid the fallacy is to avoid tinkering with someone else’s argument: Stick to the argument as presented (if available) Avoid adding premises and/or rewording; if you must do so (and sometimes we must) check and re-check to make sure that your interpretation is has a firm basis in what the arguer actually says. 23 The Ad Hominem Fallacy Ad hominem < Latin “to the man” (as opposed to the argument). “To reason from premises about the backgrounds, personalities, characters or circumstances of people to substantive conclusions about their arguments is to commit the ad hominem fallacy unless the premises are relevant to the conclusion because it is about the person or depends on acceptance of that person’s authority or testimony.” (185-6) 24 12 Reportive context Ad hominem arguments are almost always defective from a logical point of view. Yet they are a common tactic in real-world debates (especially legal and political debates). Sadly, they are all-too-often practically effective. 25 A “Natural” Human Weakness? A Govier points out, many a good idea has been rejected because the person proposing it didn’t belong to the “right” class or race or gender or religion or ethnic group. In logical terms, this sort of prejudice is not simply unattractive or unethical it is flat out mistaken: The characteristics of the person offering the argument are one thing; the merits of the argument are another. 26 13 A Special Case of Ad Hominem: To Quoque To quoque < Latin “you too” E.g.: Doctor (puffing on a cigarette): “Smoking is damaging your health. You should quit now.” You: “How can I believe you when you say that? You smoke too!” 27 Guilt by Association The fallacy of guilt by association is committed when a person or his or her views are criticized on the basis a supposed link between that person and a group or movement believed to be disreputable. E.g., “Voluntary euthanasia is wrong. Hitler and the Nazis practiced it.” 28 14 Fallacious Appeal to Popularity Or, in logicians’ lingo: argumentum ad populam Examples: “20,000 Elvis fans can’t be wrong” “Everybody’s doing it” “Isn’t that what most people think?” “Everybody knows that X” 29 Govier’s Definition The appeal to popularity is a fallacy that occurs when people seek to infer merit or truth from popularity. It is known as the fallacy of bandwagon jumping or, in the Latin, ad populam. The premise or premises of such an argument indicate that some product or belief is popular. … The conclusion of the argument is that you should accept [the argument] because it is popular. 30 15 A Special Case: Fallacious Appeal to Tradition A variation on the ad populam in which the audience is asked to accept the merit or truth of some claim or practice because that claim or practice is traditionally accepted. Many traditions are valuable. Possibly the health of a community depends on maintaining at least some traditions. But traditions are not immune from rational criticism just because they are traditions. Consider: foot-binding, clitorodectomy 31 Fallacious Appeals to Ignorance Or, in logicians’ lingo: argumentum ad ignorantiam. An appeal to a lack of evidence in support of some positive conclusion. E.g., 1. We don’t know that S is true Therefore, 2. S is false 32 16 Reportive Context: Argumentum ad ignorantiam Especially common in connection with things that some/most people think do not exist: Extraterrestrial life, God, telepathy, reincarnation, unicorns, WMDs … 33 Rumsfeld: There are things we know that we know. These are the known unknowns—that is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know—but there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we do not know we don’t know. So when we do the best we can and pull all this information, we then say well that’s basically what we see as the situation, there is really only the known knowns and the known unknowns. And each year we discover a few more of those unknown unknowns. 34 17 From ignorance, Govier rightly says, we can infer only lack of knowledge. We cannot infer truth or falsity or probability or improbability from the absence of evidence. One exception: In an empirical investigation of discoverable entities (“we should find Xs here, according to our theory”), the absence of evidence may rightly be taken as evidence of the non-existence of those entities in the context under investigation. 35 Some Other, Related, Fallacies Argumentum as misericordiam: Appeal to pity Accept my conclusion or I’ll be sad, accept my conclusion or I will suffer and/or be pitiable. Argumentum ad baculum: Appeal to force Accept my conclusion or you will suffer. 36 18