Re(caste)ing Equality Theory: Will Grutter Survive Itself by 2028?

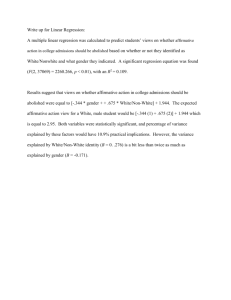

advertisement