A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library

Materials Budgets

Wanda V Dole

Dean of Libraries, Washburn University, Topeka Kansas 66621, USA

Abstract

Academic librarians have proposed a variety of methods and formulae for the allocation of library materials budgets by discipline and by format. Percentage Based Allocations

(PBA) is a method that uses simple institutional statistics to create a model for allocation.

First proposed by David Genaway in 1986 (Genaway, 1986a), it is a method by which the percentage of the library’s budget allocated to each discipline is equal to the percentage of the total university budget for instruction and departmental research received by the corresponding academic department or programme.

This paper examines the application of PBA at two academic libraries of very different size and type: a large academic research and a small comprehensive university library.

It discusses the rationale for selecting PBA, and compares PBA with other allocation methods or formulae. It postulates that PBA is an objective method for the distribution of library materials budget funds in alignment with university and library priorities. The paper also examines the question of PBA’s scalability to small and medium-sized institutions.

The literature does not contain any examples of implementation of PBA other than that at the two institutions studied.

Introduction

The allocation of an academic library’s materials budget is a challenging process.

There is a dynamic tension between devising allocations that correctly reflect institutional priorities and explaining those allocations within a politically charged environment.

There are three basic methods of allocation mentioned in the literature: allocation formulae, the historical method, and PBA

(Genaway, 1986a). Allocation formulae for academic libraries are based on publishing industry and local statistics such as publishing cost and output, enrolment, number of faculty, and number and level of degree programmes. In the historical method, allocations are based on past practice and historical data; increases to the total budget are added as increments to the past year’s allocations. Percentage Based

Allocation uses institutional statistics to build a mathematical model for the allocation of funds on subject or departmental lines. This paper discusses

PBA in depth.

Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002

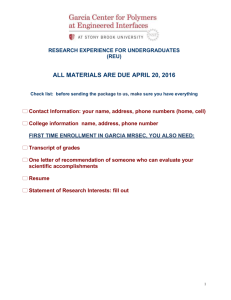

Scarce resources “inevitably cause the spotlight to focus on the methodology of the distribution technique employed.” (Eave,

1989, p 130). Strategic planning and library self-studies furnish the impetus for the examination of a library’s allocation system.

At the State University of New York at

Stony Brook in the early 1990s and

Washburn University in 2002, the combination of strategic planning, an

Association of Research Libraries (ARL)

Collection Analysis Project, and scarce resources led to such an examination and to the consideration of PBA as a new system of allocation.

Allocation can be defined as “the process of distributing available financial resources at the disposal of an organization for specified purchases and functions.” (Shreeve, 1991, p 17). There is a vast body of literature on how and why to allocate the library materials … so vast, according to Lowry

(1992, p 122), that “Rare is the faculty member, or for that matter the librarian, who is willing to digest the mountain of

98

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets published literature necessary to developing a comprehensive plan that satisfies the general institutional interests.” Several review articles provide an overview of this literature (German and Schmidt, 2001; Rein,

1993; Budd, 1991; Packer, 1988; Werking,

1988; Sellen, 1987; Sanders, 1983; Yunker and Covey, 1980; Schad, 1979). Much of the literature describes allocation formulae in theory and in practice. Theoretical articles far outnumber those describing formulae that have actually been implemented and deemed successful. Lowry suggests that the formulae discussed in the literature are often

“akin to Rube Goldberg contraptions, fascinating to watch, but overly elaborate means to ends.” (Lowry, 1992, p 122).

The ALA Glossary of Library and

Information Science defines the formula budget as “a budget in which the allocations are based on pre-established standards, such as an established expenditure for materials per student in an academic library.” (Young et al , 1983, p 100). The literature on budget allocation states that objective, quantitative data should be used to determine relative need for funding among the different allocation units. Three categories of objective data are mentioned in the literature of budget allocation:

1.

Factors relating to the university and library users

2.

Measure of library use

3.

Size and cost of the literature in a specific discipline

Librarians have used all or some of these categories as variables in devising formulae aimed at quantifying allocation decisions.

In 1984, Shirk questioned whether any of the published allocation formulae could rightly be considered a “formula” (Shirk, 1984). He pointed out that a formula must be scientific

(i.e. theoretically and empirically sound) to be a viable, long-term budgeting technique.

According to Shirk, an allocations formula must have the following essential characteristics in order to be considered scientific:

1.

It is an explicit, mathematical expression of a theorem

2.

It can be empirically tested (Shirk, 1984, p 39)

Shirk dismissed most published allocation formulae as not scientific, but merely

“notationally simplified expressions of arbitrary procedures.” They are “arbitrary conventions” whose success depends on their political acceptance, not upon a defensible theoretical framework that relates objective variables to the collection’s performance in a meaningful way (Shirk,

1984, p 45-46).

The actual use of allocation formulae has decreased during the last 60 years from

73.3% of US college libraries in the 1940s

(Muller, 1941, p 321), to 67.5% of southeastern academic libraries in the 1970s

(Greaves, 1974, p 142) and finally to only

40.6% in the late 1980s (Budd and Adams,

1989, p 384) and 40% in the 1990s (Tuten and Jones, 1995).

Percentage Based Allocation

In 1986 David Genaway proposed

Percentage Based Allocation (PBA) as a simplified approach to the allocation of the library materials budget (Genaway, 1986a).

He suggested that “any method used to allocate university-wide resources will ultimately be reflected at one point … the budget line given to each college or department for instruction and research.

Generally, this figure reflects accreditation standards, number of faculty, student credit hours, new programs, level of courses taught, etc. In many cases, it also reflects complex formulas used at the state level that use various subsidy methods.” (Genaway,

1986a, p 289).

Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002 99

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Genaway goes on to outline how the university’s “bottom line” figure for

“instructional and departmental research”

(I&DR) or similar category for each college or department could be used as the basis for allocating the library acquisitions budget.

(Ibid). “Essentially, the percent of I&DR (or similar budget line) budget received by each department or college would be used to determine the library allocation: i.e. each academic unit would receive the same percent of the library materials budget that it received for instruction and research from the university’s budget. Simply put, the

“bottom line” of a college or university’s budget for instruction and research for a given academic unit divided by the institution’s total for instruction and research equals the percent of the university’s budget received by each college or school. This percent equals the percent of allocated library budget that would be received by that college or school.”

(Genaway, 1986a, p 289).

Genaway bases PBA on the following assumptions:

1.

A balanced collection of library materials reflecting the curricula of an institution is desirable

2.

The college or university administration applies the state regents’ formulas, governing boards, or similar rational methods of determining allocations to the institution to the redistribution of the funds intra-university

3.

There is a positive correlation between an academic department’s instructional and research budget and library intensiveness (Genaway, 1986a, p 291)

He lists the following advantages to PBA

(Genaway, 1986a, p 291):

1.

PBA is a dynamic rather than static method. Although allocations would not change drastically from year to year, they would reflect long-term changes in the college or university’s curriculum.

The method is stable enough to be functional. Most present allocations have been constant for several years

2.

It incorporates all of the items found in most formulas, although these items may be covert or indirect. The institutional allocation to each department does or at least should reflect all the criteria normally found in most formulas

3.

It is not single-element driven, although it is a single element and simple to determine and administer. It is not

“driven” solely by student credit hours or courses, although it is indirectly influenced by these factors

4.

It is likely to be considered more equitable by a greater number of department heads and faculty than many existing methods or other formulas. This might be especially true if there were no systematic method of allocation when the PBA approach was introduced, and allocation was based on previous spending patterns instead. However, if it resulted in any losses over the status quo method of allocation, it might not be as accepted

5.

It could be applied at the school, college, departmental or programme level

He also cites possible disadvantages

(Genaway, 1968a, p 291-2):

1.

It is based on the assumption that the college or university’s instructional budget is subdivided on the basis of a rational plan or formula that incorporates all the usual elements for determining budgets. This may or may not be the case

2.

It assumes a high positive correlation between size of an academic unit’s budget and that unit’s library needs or intensiveness. Academic departments with large credit hour production and, hence, usually a high budget with a large

100 Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets number of faculty may have limited need for library acquisitions. Health and

Physical Education is an example. Other disciplines, such as English and

Chemistry, may be more library intensive and require acquisition monies in excess of the proportion allocated for instruction and research. If audiovisual materials are a part of the library acquisitions budget, this argument might be negated, since the more multi-media oriented disciplines would then remain library intensive

3.

It could result in a substantial reduction in dollar amounts given to a college when initially applied. This would require a period of adjustment. If this occurs, a gradual “phasing-in” or shifting to the new method could be accomplished over a period of two or three years. Perhaps this might be accomplished by using the average between the two percentages each year until this gap has diminished.

Theoretically, it should become narrower each year

4.

In private colleges or universities, the amount of the instruction and research budget allocated to each school or college might be more difficult to obtain, depending on the nature of the administration. In state-supported colleges and universities, these figures are usually considered a matter of public record and should be readily available

Writing in 1986, Genaway suggested that

PBA might “work best in an institution where the library acquisitions budget includes audiovisual materials as well as books, periodicals, and micro format items, such as a community college or small general college. Inclusion of audiovisual materials would balance the needs of more physical- and skill-oriented disciplines, such as physical education, against more book-intensive disciplines such as history and literature.” (Genaway, 1986a, p 292). In today’s environment, an inclusive budget would cover newer formats, such as electronic resources, introduced after

Genaway developed PBA in 1986.

When Genaway proposed PBA in 1986 he was not aware of any institutions using the method. A literature search has not revealed any publications on the use of PBA to date.

In 1992 when evaluating allocation formulae for use in his study, Young used the criterion that the formula must be formally accepted and used by the institution that developed it.

Using this criterion, he rejected PBA

(Young, 1992, p 231), which he erroneously considered a formula.

Rein cites PBA as an example of “allocation without formula” and calls it “seductive” as

“it appears to dovetail collection development goals into university priorities

... is comprehensible both to library and non-library staff; and it is by far the least time-intensive procedure available” (Rein,

1993, p 28-29). She cites as a drawback the assumptions that per capita cost per resource unit is the same for all academic departments, or that the university has a weighted cost factor built into its teaching and research budget which directly correlates to the differences in library materials costs for each department (Rein,

1993, p 29).

PBA at two institutions

Stony Brook: Background

The State University of New York (SUNY) at Stony Brook is a young public Carnegie

Research University I. Founded in 1956 as a training institution for teachers of mathematics and science at the secondary and community college level, Stony Brook rapidly expanded its mission to include the full range of undergraduate and graduate programs through the doctorate in the humanities, social sciences, sciences, and engineering. In 2001/02 the University enrolled 20,855 students: 13,646 undergraduates in 57 academic majors and

7,209 graduate and professional students in

Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002 101

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

69 areas; 1,849 full- and part-time faculty teach in seventy departments. Major academic units include the College of Arts and Sciences, College of Engineering and

Applied Sciences and the Health Sciences

Center.

The Stony Brook library system consists of the Frank Melville Jr Memorial Library, which houses the largest portion of the collections, and seven branch libraries. A

Health Sciences Library is administered separately. Throughout this paper, the terms library, libraries, and library system refer to the Melville Library and its branches, excluding the Health Sciences Library.

During the 1960s and 1970s the library system received generous funding for collection development and attempted to acquire materials at the comprehensive level in most fields. After growing rapidly in the

1960s and 1970s, the acquisitions budget thereafter levelled off and failed to keep pace with inflation. The level of collecting fell from 91,983 monographic volumes added in 1970/71 to 21,000 in 1990/91 (the year preceding Strategic Planning) and is now at 26,755 (2001/02). The number of purchased serials declined from 11,111

1970/71 to 8,060 1990/91 is now 6,117 print journals, 11,709 e-journals. There are also

451 databases currently purchased

(2001/02).

Stony Brook: Strategic planning and CAP studies

During the Stony Brook Libraries’ 1991/92 strategic planning effort, a Collection

Development Task Force examined the

Libraries’ collection development programme in relation to external factors and to the mission and goals of the university. In its June 1992 final report, the

Task Force concluded that a number of actions were necessary to insure that the collection management and development programme was responsive to the university’s priorities and goals (State

University of New York at Stony Brook

Libraries, 1992b). The Task Force recommended that the Libraries

•

Conduct the ARL/OMS (Association of

Research Libraries/Office of

Management Services) Collection

Analysis Project ... to help develop collection development policies/procedures and mechanisms for keeping collection development in touch with the changes in the University programmes and missions

•

Develop a rational allocation of resources (library materials budget) which reflects the strengths/missions/goals of the

University

Both recommendations were included in the libraries’ Strategic Plan and accepted for implementation (State University of New

York at Stony Brook Libraries , 1992a).

In late 1992 and early 1993, the Libraries conducted the ARL/OMS Collection

Analysis Project (CAP), “as a crucial first step in promoting the necessary change to collection management and development at

Stony Brook into conformity with the best accepted professional practices and thereby make it more responsive to the University’s priorities and needs” (State University of

New York at Stony Brook Libraries, 1993a).

Four task forces were created by the CAP

Study Team to examine key issues related to collection management, and to make recommendations for improving the efficacy of the Libraries’ collection development and management programme. This paper examines the work of the Task Force

Funding and Materials Budget Allocation whose charge was to examine the Libraries’ budget process and propose alternatives for allocating the acquisitions and access budget.

After assessing the strengths and weaknesses of the Libraries’ allocation process, the Task

102 Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Force found that the failings of the

Libraries’ allocation system were due mostly to its inability to adapt to changes in the

University’s academic and research programs (State University of New York at

Stony Brook Libraries , 1993b). The Task

Force also identified several weaknesses in the budget process used by the Libraries

(State University of New York at Stony

Brook Libraries , 1993a, p 1-3). The allocation process used by Stony Brook up to 1993 was for the most part historical.

Materials funds were distributed incrementally to each allocation unit according to a paradigm devised in the

1970s. The rationale and criteria for this process had never been systematically examined.

There were many observations of the allocation process. Those most relevant to

PBA are:

1.

Allocations were not based on objective criteria, which makes it difficult to defend budget decisions

2.

Allocation units were not adequately correlated with the University’s curriculum and do not entirely reflect the changing academic emphases of the

University. Some allocations perpetuate past needs, which may no longer be valid

3.

Automatic expenditures for periodical subscriptions and standing orders can result in the loss of flexibility to purchase other library materials

4.

No portion of the budget was held for contingencies, and the Libraries did not receive extra funding from the

University for new programmes.

One-time adjustments for new programmes were possible but they were not added to the budget base

5.

The budget process did not provide for the impact of new technologies, and did not address the issue of on-site ownership versus access. As a result, in the early 1990s the Libraries experienced

6.

difficulties acquiring electronic information resources

There was no provision for adjusting allocations in relation to inflation

7.

A strategy for dealing with the costs of interlibrary loan, document delivery, and database searching had never been developed

8.

The budget process was outdated and did not support the systematic and consistent development of the collections. There was no mechanism for periodic review of the process

The Task Force decided at the outset that it would not state the obvious by advocating increased funding for the Libraries, but drew up recommendations that would be applicable to the Libraries’ budgeting process regardless of levels of funding. The recommendations developed by the Task

Force addressed each of the weaknesses identified in the analysis of the Libraries’ allocation process.

Stony Brook: CAP recommendations

After reviewing the literature on budget allocation, the Task Force studied and discussed possible solutions to the problems identified in the analysis of current practice and developed the following set of recommendations addressing each of the weaknesses listed above (State University of

New York at Stony Brook Libraries p 3-14):

, 1993a,

1.

Develop a written statement describing the allocation process and the criteria upon which allocation decisions are based

2.

Use objective data in distributing the

Libraries’ acquisitions and access budget among various allocation units.

Percentage Based Allocation (PBA) was recommended as a good starting point for accomplishing this

Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002 103

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

3.

Re-examine the choice of allocation units and correlate discipline with

Library of Congress Classification numbers. Create a separate allocation unit for access to information

4.

Provide each fund with a single allocation for monographs and continuations

5.

Establish a separate allocation to cover contingencies and special purchases

6.

Develop a mechanism for periodic review of the allocation process

All of the recommendations were accepted by the CAP Steering Committee and included in the final CAP recommendations

(State University of New York at Stony

Brook Libraries , 1993a). In his Preface to the CAP Final Report , John Brewster Smith, then Dean and Director of Libraries, singled out PBA as one of the study’s most difficult, but most important, recommendations, because it called for reviewing and adjusting historical allocations used for so long by the

Library. He recognised that PBA would be

“an exceedingly sensitive undertaking and one that will require understanding and support of higher University administration, especially the academic deans.” (State

University of New York at Stony Brook

Libraries , 1993a, p ii).

Stony Brook’s rationale for PBA

Why did the Stony Brook Task Force chose

PBA instead of one of the numerous allocation formulae described in the literature? In its Final Report, the Stony

Brook Task Force concluded that most formulae are too constrictive, and the choice, application, and weighting of variables are often arbitrary and subjective. The Task

Force found, however, that Percentage

Based Allocation (PBA) would provide a good starting point for identifying possible imbalances and inequities in a library’s allocations.

PBA is a method by which the percentage of the library’s material budget allocated to each discipline is equal to the percentage of the parent institution’s instruction and departmental research funding (I&DR) received by the corresponding academic department or program (Genaway, 1986a).

All of the factors relating to the university and library users have presumably been applied and weighted by university administrators; therefore, the allocations arrived at are pragmatic and politically defendable in that they reflect the university’s strength and goals as determined by the university administration.

The Task Force did not recommend that allocations be based solely on PBA.

Although PBA may assist in determining the amount of support needed for departments, it is not practical for allocating funds to library departments (such as Reference, Special

Collections, Maps, etc) and it does not take into account the publication output and cost or differences in need and demand for library materials among various disciplines.

The Task Force believed that these are important factors that should also be examined and analysed during the allocation process.

PBA provided the foundation for a codified but flexible budget allocation process that also includes several types of objective data.

The mathematical scheme is derived from

PBA documents and epitomises past practice and demonstrates accountability when asking for funding. Written policies and procedures (such as PBA) are essential to the continuing review and improvement of the budgeting process. The Task Force concluded that a combination of codified policy, quantitative data, and professional judgment would lead to acceptable decisions and a valid process for allocating the library’s materials budget.

104 Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002

Application of PBA at Stony Brook

The SUNY Stony Brook Libraries have been using PBA to allocate the library acquisitions and access budget since 1994.

The following institutional statistics are used to build allocations:

1.

The University’s Operating Budget , an annual publication that lists departmental allocations by object code

2.

Historical data from the Library’s acquisition department: the previous year’s serials and monograph expenditures by fund code

3.

The Library’s acquisition and access budget

The process requires several calculations.

The University’s Operating Budget is used to create a mathematical model: each academic department’s allocation for salary and wages (I&DR) is divided by the total

University I&DR to obtain the percentage it represents of the total.

The PBA percentages are then applied to the

Library’s acquisition budget, after funds have been set aside for access (10-15% of the total acquisitions budget) and contingency (5% of the budget after access funds have been subtracted).

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Table 1 shows the dollar figures for the

University’s 1997/98 I&DR (the basis for the 1998/99 PBA) and the PBA for 1998/99.

One of the guidelines that Stony Brook applied to PBA is not to increase or decrease an allocation by more than 10%. Table 2 shows how this “comfort zone” of 10% was used in building the allocations. The PBA allocation is compared to the previous year’s actual expenditures. If the difference between the two was greater than 10%, the comfort zone figure was the actual increase or decrease. The resulting allocations were called “modified PBA”. Table 3 compares the historical allocations in place before

PBA was initiated with PBA allocations and modified PBA allocations (the “actual expenditures”) over time. Although there are still some glaring gaps between the PBA figure and the actual expenditures for several subjects, slow and steady progress has been made toward equitable distribution.

Stony Brook’s CAP recommended that there be one allocation for both monographs and continuations. This means that the PBA allocation is the total allocation for a subject and, in order to establish a monograph allocation, the cost of serials (usually the previous year’s actual expenditures with an inflationary increase) is subtracted from the

PBA allocation (Table 4).

Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002 105

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Table 1 Calculation of PBA Stony Brook 1998-1999

HUMANITIES AND

SOCIAL SCIENCES

Total x 43%

Art

Classics/Comp.Stu/

Studies/Rel

English

French/Italian

Asian Studies

German/Slavic

Hispanic

Philosophy

Women’s Studies

Theater

Anthropology

Africana

Economics

History

Linguistics

Political Science

Psychology

Social Science/

Sociology

Management

CED

Subtotal

LIBRARY DEPTS

Library Science

AV/Film Studies

Documents

Maps

Reference

Special Collections

General Interest/

Periodicals/Papers

Subtotal

MUSIC

Music

SCIENCES

Biology

Chemistry

ESS

Math/Appl. Math

Physics/Astronomy

Engineering

Computer Science

MASIC

Subtotal

TOTAL

I & D R 97/98 % of Total PBA 98/99

$ 1,138,642

$ 1,029,034

5.3%

4.7%

49,296

43,715

$ 1,900,758 8.8% 81,849

$ 775,598

$ 20,000

$ 433,801

$ 795,598

3.6%

0.09%

2.0%

3.7%

33,484

837

18,602

34,414

$ 1,510,594

$ 230,359

$ 573,555

$ 854,792

$ 368,442

$ 1,523,931

$ 1,608,633

$ 685,824

7.0%

1.1%

2.7%

4.0%

1.7%

7.1%

7.4%

3.1%

65,107

10,231

25,113

37,204

15,812

66,038

68,828

28,833

$ 1,355,514

$ 2,842,375

$ 430,014

$ 1,479,354

$ 1,148,297

$ 866,689

6.3%

13.3%

8.9%

5.3%

4.0%

58,597

123,704

82,780

49,296

37,204

$ 21,571,804 100.0% 930,944

26,846

15,653

97,333

3,489

192,884

4,671

74,492

Total X 4%

Total x 53%

$ 4,577,058

$ 2,710,341

$ 1,271,726

$ 4,680,336

$ 5,857,263

$ 4,669,184

$ 2,069,486

$ 934,000

$ 26,769,394

$ 50,360,832

17.0%

10.0%

4.8%

17.5%

22.0%

17.5%

7.7%

3.5%

100.0%

415,368

132,637

298,766

175,745

84,357

307,553

386,638

307,553

135,323

61,511

1,757,446

3,236,395

106 Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Table 2 - PBA comfort zone Stony Brook, 1998-1999

HUMANITIES/SOCIAL SCIENCES

Actual exp.

97/98

Art

Classics/Comp.

Studies/Rel

English

French/Italian

Asian Studies

German/Slavic

Hispanic

Philosophy

Women’s Studies

Theater

Anthropology

PBA

98/99

$

Difference

$

Difference

Comfort

Zone

Modified

PBA

$33,975

$35,183

$49,296 ($15,321)

$43,715 ($8,532)

-45%

-24%

$3,398

$3,518

$37,236

$37,359

$59,894 $81,849 ($21,955) -37% $5,989 $63,726

$42,684 $33,484 $9,200 22% $4,268 $40,384

$25,194

$27,689

$37,124

$60,505

$38,841

$9,303

$32,937

$837

$18,602

$34,414

$65,107

$10,231

$24,357

$9,087

$2,710

($4,602)

$28,610

$25,113 ($15,810)

$37,204 ($4,267)

97%

33%

7%

-8%

74%

-170%

-13%

$2,519

$2,769

$3,712

$6,051

$3,884

$930

$3,294

$27,000

$24,920

$34,414

$65,107

$30,970

$13,275

$36,231

Africana

Economics

History

Linguistics

Political Science

Psychology

Social Science/

Sociology

Management

CED

Subtotal

Documents

Maps

Reference

Periodicals/Papers

Subtotal

MUSIC

Music

SCIENCES

Biology

Chemistry

ESS

Math/Appl. Math

Physics

Engineering

Computer Science

MASIC

General Science

Subtotal

TOTAL

$16,307

$95,346

$71,982

$27,154

$54,528

$83,801

$55,822 $82,780 ($26,958) -48% $5,582 $61,404

$23,175

$28,576

$860,020

$26,846

$15,653

$97,333

$3,489

$15,812

$66,038

$68,828

$28,833

$495

$29,308

$3,154

($1,679)

$58,597 ($4,069)

$123,704 ($39,903)

$49,296 ($26,121)

$37,204 ($8,628)

$930,944

$26,846

$15,653

$97,333

$3,489

($70,924)

3%

31%

4%

-6%

-7%

-48%

-113%

-30%

-8%

$1,631

$9,535

$7,198

$2,715

$5,453

$8,380

$2,318

$2,858

$86,002

$15,812

$85,811

$71,000

$32,833

$58,597

$92,181

$26,493

$31,361

$886,114

$26,846

$15,653

$97,333

$3,489

$192,884

$4,671

$74,492

$192,884

$4,671

$74,492

$192,884

$4,671

$74,492

$415,368

$88,754

$415,368

$132,637 ($43,883) -49% $8,875

$415,368

$97,629

$304,185

$395,133

$164,036

$206,497

$263,532

$356,514

$101,787

$64,368

$17,523

$298,766

$175,745

$84,357

$307,553

$386,638

$307,553

$5,419

$219,388

$79,679

($101,056)

($123,106)

$48,961

$135,323 ($33,536)

$61,511

$25,000

$2,857

($7,477)

$1,873,575 $1,782,446 $91,129

$3,237,717 $3,261,395 ($23,678)

2%

56%

49%

-49%

-47%

14%

-33%

4%

-43%

5%

-1%

$30,419

$39,513

$16,404

$298,766

$355,620

$140,000

$227,147 $20,650

$26,353

$35,651

$10,179

$6,437

$1,752

$319,811

$320,863

$111,966

$61,511

$25,000

$187,358 $1,860,684

$3,259,795

Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002 107

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Table 3 Comparison of historical allocations and PBA 1993-1999

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES

Historical

1993

PBA

1994

Actual

Expend

1995 1994/1995

PBA

1995

Actual

Expend

1996 1995/1996

PBA

1996

Actual

Expend

1997 1996/1997

PBA

1997

Actual

Expend

1998 1997/1998

PBA

1998

1999

Art

Classics/Comp/Studies/

Rel.

English

French/Italian

German/Slavic

Hispanic

Philosophy

Women’s Studies

Theater

Anthropology

Africana

Economics

History

Linguistics

Political Science

Psychology

Social Science/Sociology

Management

CED

TOTAL

4.55

5.44

4.42

4.39

4.43

4.38

5.61

4.57

5.44

5.07

5.54

4.93

4.17

4.18

5.04

4.83

3.95

4.09

5.3

4.7

6.96

12.42

7.09

3.87

7.59

6.13

8.72

3.35

6.95

5.22

10.36

3.68

7.14

4.98

9.27

3.84

6.96

8.8

4.96

2.93

3.6

0.09

5.62

4.46

6.18

2.02

2.57

4.40

7.41

0.24

5.83

4.53

6.89

2.11

2.18

3.05

5.87

0.58

4.21

3.71

6.82

1.18

2.46

3.06

6.90

0.72

4.31

4.50

6.32

4.24

2.62

3.57

7.09

0.75

3.22

4.32

7.04

4.52

2

3.7

7

1.1

1.97

3.73

1.46

11.34

3.41

3.98

1.58

7.84

8.67

4.51

8.52

2.24

8.73

5.47

8.73

14.44

1.22

4.28

1.51

11.80

3.83

4.26

1.09

5.24

8.93

7.21

3.79

2.53

8.31

5.86

9.32

17.22

1.68

4.04

1.06

12.05

11.56

3.70

4.05

1.37

5.84

8.16

3.86

2.90

7.84

5.99

9.54

13.95

1.21

3.68

1.90

13.72

9.21

3.23

6.55

9.41

3.15

4.18

1.49

7.61

7.48

3.06

6.08

14.30

1.08

3.83

1.90

11.09

8.37

3.16

6.34

9.74

2.7

4

1.7

7.1

7.4

3.1

6.3

13.3

7.17

10.28

0.69

0.52

8.14

9.43

1.71

6.85

8.44

8.76

0.53

6.42

9.69

1.21

9.18

5.17

6.49

2.69

8.9

5.3

0.58

1.88

0.63

3.80

0.45

1.68

0.35

1.20

3.32

4

100.00 100.00

100.00 100.00

100.00 100.00

100.00 100.00

100.00

100.0

Maps

Documents

Reference

Periodicals/Papers

TOTAL

MUSIC

Music

SCIENCES

Biology

Chemistry

ESS

Math/Appl. Math

Physics/Astronomy

Engineering

Computer Science

MASIC

TOTAL

7.02 5.22 4.28 3.53 3.77

1.53 2.04 1.37 0.84 0.84

23.26 15.34 27.61 27.48 23.43

47.98 54.56 44.56 47.70 46.44

0.99 0.99 0.74 0.87 1.12

11.47 12.92 11.15 13.17 17.93

100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00

2.50

4.80

2.80

3.60

2.60

4.90

2.69

4.19

2.76

4

100.00 100.00

100.00 100.00

100.00 100.00

100.00 100.00

100.00

100.0

20.18

18.70

25.30

12.85

10.94

8.10

9.75

16.11

11.37

14.27

17.44

16.00

4.98

0.00

8.57

5.36

18.51

22.60

9.26

10.03

12.99

18.36

5.38

18.14

11.34

7.67

12.85

22.09

12.96

6.53

2.88

8.39

18.58

22.77

9.11

9.72

13.62

18.55

5.19

16.00

10.44

7.00

18.40

18.75

16.77

8.10

2.46

4.54

17.16

23.20

8.61

9.55

13.93

19.37

5.18

2.99

16.28

10.22

6.88

17.28

18.85

16.74

8.64

5.10

16.39

21.29

8.84

11.13

14.20

19.21

5.48

3.47

17

10

4.8

17.5

22

17.5

7.7

3.5

100.00 100.00

100.00 100.00

100.00 100.00

100.00 100.00

100.00

100.0

108 Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

FUND

Africana

Anthropology

Art

A/V

Biology

Continuing Ed

Chemistry

Chinese

Classics

Comp. Literature

Computer Science

Documents

ESS

Economics

Engineering

English

Film Studies

French

German

General Science

History

Italian

Japanese

Korean

Library Science

Linguistics

Maps

MASIC

Mathematics

Music

Public Admin.

Philosopy

Physics

Political Science

Pyschology

Reference

Religious Studies

Russian

Sociology

Spanish

Special Collections

Theater

Women’s Studies

Gen. Int. Newspapers

Gen. Int. Periodicals

General Humanities

SUBTOTALS

ACCESS

BINDING

POSTAGE

SUBTOTAL

TOTAL ALLOCATIONS

Table 4 Derivation of monographic allocation Stony Brook 1998-1999

FY 1998/99

Allocation

$15,812

$32,816

$37,236

$7,826

$298,766

$31,361

$355,620

$11,000

$4,359

$17,000

$91,608

$97,333

$158,032

FY 1998/99

Serials

$5,000

$12,000

$6,900

$125

$318,000

$25,000

$377,136

$1,500

$2,000

$7,000

$77,000

$85,000

$120,000

FY 1998/99

Monographs

$10,812

$20,816

$30,336

$7,701

$28,000

$3,161

$25,000

$9,500

$2,359

$10,000

$25,000

$12,333

$38,032

$136,247

$320,863

$63,726

$7,826

$61,000

$327,928

$9,275

$2,500

$34,238

$28,000

$54,451

$5,326

$18,384

$16,700

$25,000

$68,828

$7,088

$4,400

$11,750

$18,073

$11,296

$12,300

$13,250

$50,755

$18,000

$10,000

$4,824

$462

$13,176

$9,538

$6,000 $3,900

$26,846 $21,000 $5,846

$28,833

$4,000

$57,931

$227,147

$97,629

$25,493

$65,107

$289,885

$14,000

$1,337

$57,000

$188,593

$22,000

$16,450

$20,060

$2,601,071

$14,833

$2,663

$931

$35,000

$75,629

$10,834

$45,047

$25,000

$58,597

$92,181

$192,884

$16,000

$14,190

$61,404

$34,414

$4,671

$13,275

$30,970

$7,639

$28,190

$63,000

$162,678

$7,000

$5,870

$28,630

$5,500

$1,094

$3,680

$2,500

$7,639

$30,407

$29,181

$30,206

$9,000

$8,320

$32,774

$28,914

$3,577

$9,595

$28,470

$47,474

$1,856

$47,474

$1,856

$3,248,769 $4,790,583 $885,507

$595,711

$70,000

$12,000

$677,711

$3,926,480

Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002 109

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Washburn University: Background

Founded in 1865 as a church-related college,

Washburn University is a municipal university with an enrolment of approximately 6,200 students and a full-time faculty of 250. It is a Carnegie Master’s

University I with broad-based liberal arts and professional education programmes leading to 190 certificate, associate, baccalaureate, master’s and juris doctor degrees. The primary emphasis is on undergraduate education. The University

Libraries (the Mabee Library and a

Curriculum Resources Center) serve the needs of undergraduate and graduate instruction in the humanities and social science. There is a separately administered

Law Library. In this paper, the terms Library and Libraries refer to the Mabee Library and the Curriculum Resources Center.

During the last two decades, the Libraries have received smaller and smaller additions to the materials budget. Between 1980/81 and 1985/86, the Libraries received relatively large increases between 6% and

25%. Between 1985/86 and the present

(2001/02) the increases were much smaller.

In fact there were decreases in the monograph budget between 1995/96 and

1999/00. The budget has been flat since

1999. The periodicals budget has dropped nearly 30% since 1980/81. The Libraries’ materials budgets have not kept pace with inflation; thus, there has been a decline in the number of monographs and media items purchased and cancellation of periodical subscriptions. Approximately 5,000 monograph volumes are purchased annually; the number of purchased serials declined from 869 in 1998/99 to 385 in 2000/01.

There has been a steady growth in the number and percentage of the library materials budget devoted to electronic resources. The investment in these resources nearly doubled in five years, from 12% of the materials budget in 1994/95 to 20% in

1999/00.

Washburn: Strategic planning and CAP

In 2000 the Washburn University Libraries began a strategic planning process that resulted in the Washburn University, Mabee

Library, Strategic Plan, 2000-03 (Washburn

University Mabee Library, 2000) . One of the major goals identified in the Strategic Plan involved collection development. The goal was “to acquire, preserve, and provide access to a diverse collection of print and non-print information resources that are directly aligned with the University’s academic priorities.” Various strategies to achieve this goal were developed including the recommendation that the Libraries contact ARL to learn if it still offered the

Collection Analysis Project (CAP) as an assisted self-study.

With the assistance of a facilitator from the

Association of Research Libraries,

Washburn began a CAP study in November

2001 to “assess the efficacy of … [the] collection management program and policies” and is still working on the process.

Washburn’s CAP resembles Stony Brook’s in goals and procedure. Three task forces were created to examine key issues and to make recommendations for the improvement of the collection development and management programme.

The Task Force on Funding and Materials

Budget Allocation was given the assignment to examine the current method of funding and materials budget allocation and to make recommendations for change where appropriate. It was specifically asked to examine PBA. The Task Force began its work in June 2002 and at this time (August

2002) has done only preliminary work with

PBA.

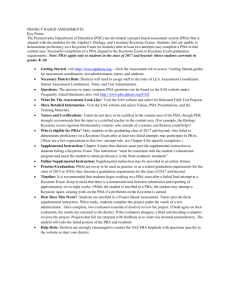

The Task Force identified the following major weaknesses in the Washburn budget process:

1.

A complex allocation formula devised in

1980s for monographs (Table 5)

110 Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

2.

A totally historical periodicals budget.

There has been no attempt at a rational allocation of the periodicals budget and, until 2002, periodical expenditures were not tracked by fund codes

3.

There is no statement regarding budgeting for electronic resources

4.

There is no strategy for dealing with the costs of interlibrary, document delivery and bibliographic utilities

The Task Force has done preliminary comparison of the formula used to allocate the monograph budget and PBA.

Table 5 Allocation formula for Washburn University Library

“Books and research materials fund”

1) Scope of subject literature

A.

Average book cost for each department/school from the most recent complete fiscal year as a percent of overall book cost for all academic unit book purchases (locally derived data)

B.

C.

Number of titles published in each subject during the most recent complete fiscal year as a percent of all titles published for all subjects in which the library collects (Blackwell North America supplied data based on our subject profiles)

A is weighted as 1, B is weighted as 1. (A + B)/2 = weight of 1 for this entire aspect of the formula.

2) Credit hours

A.

Lower division credit hours by department/school as a percent of all lower division hours for the most recent complete academic year (locally derived data)

B.

Upper division credit hours by department/school as a percent of all upper division hours for the most recent complete academic year (locally derived data)

C.

D.

Graduate credit hours by department/school as a percent of all graduate hours for the most recent complete academic year (locally derived data)

A is weighted as 1, B is weighted as 2, C is weighted as 3. (A + B + C) x 2 = weight of 2 for this entire aspect of the formula.

3) FTE Faculty

A.

FTE faculty by department/school as a percent of all FTE faculty for the most recent complete academic year (locally derived data)

B.

A is weighted as 1.

4) Usage

A.

B.

Class use for each department/school as a percent of total class use (locally derived data during one library survey period each semester)

Circulation by subject as a percent of total circulation (locally derived data during one library survey period each semester)

C.

A is weighted as 1, B is weighted as 1. (A + B)/2 x 1.5 = weight of 1.5 for this entire aspect of the formula.

5) Factors 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 are normalized to equal 100% and applied to 67.5% of the “Books and Research

Materials” fund.

6) No single year fluctuation of more or less than 20% than the previous allocation is allowed for any department/school.

Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002 111

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Preliminary applications at Washburn

The Washburn CAP Task Force has done only preliminary calculations based on the same data elements used at Stony Brook: the

University’s I&DR budget and historical allocations and expenditures for library materials. PBA allocations were created and compared with actual allocations and expenditures for 2000/01 (Table 6). Much work still needs to be done: identifying a comfort zone of 10%, calculating a modified

PBA and subtracting the previous year’s periodical expenditures to produce the suggested allocation for monographs. This

PBA allocation can then be compared to the amount actually allocated by formula for monographs in 2000/01 and the differences examined.

Examination of the preliminary data does show some unexpected discrepancies. For example, according to PBA (which mirrors the profile of actual university support for programs), Psychology, with master’s level programs, would receive less funding than

Mathematics, with only undergraduate programs. Does this mean that the undergraduate program in Mathematics is a higher university priority than the master’s program in Psychology? Does it mean that university I&DR is not, contrary to

Genaway’s suggestions, an indication of university priorities? Is this discrepancy idiosyncratic to Washburn or indicative of the differences (in salary structures and rewards systems) between small comprehensive universities and large research universities?

Table 6 Washburn University: Comparison of actual expenditures and PBA

DEPARTMENTS

Allied Health

Art

Biology

Business

Chemistry

Computer Science

Criminal Justice

Education

English

Health & Phys Ed.

History

Human Services

Mass Media

Mathematics

Modern Foreign Lang.

Music

Nursing

Office/Legal/Tech

Philosophy

Physics

Political Science

Psychology

Social Work

Sociology

Speech Comm.

Theatre

TOTAL

2.03%

1.08%

1.82%

4.38%

1.22%

2.34%

3.15%

3.36%

1.70%

4.05%

6.60%

4.65%

2.60%

3.25%

2.96%

1.26%

10.13%

4.92%

3.29%

1.06%

0.96%

100.00%

%

OF

TOTAL

B

1.48%

2.35%

9.31%

12.59%

7.45%

ACTUAL

EXPENDITURES

2000/01

A

$4,873.06

$7,729.58

$30,615.39

$41,428.24

$24,506.40

$5,606.88

$13,309.91

$21,719.01

$15,291.24

$8,559.17

$10,690.34

$9,735.31

$4,161.48

$6,688.03

$3,566.27

$5,991.87

$14,412.70

$4,013.76

$7,690.41

$10,349.06

$11,068.64

$33,331.05

$16,172.94

$10,820.94

$3,473.05

$3,171.14

$328,975.87

PBA

C

$12,168.10

$8,101.75

$15,162.53

$53,276.73

$7,353.39

$10,519.13

$11,009.67

$19,173.77

$23,958.29

$10,884.97

$8,977.20

$6,172.64

$8,687.16

$14,812.16

$5,329.19

$14,654.73

$19,992.20

$7,308.51

$7,543.93

$6,828.49

$10,154.82

$11,989.95

$12,438.34

$10,473.80

$7,359.27

$4,645.14

$328,975.87

4.50%

1.62%

4.45%

6.08%

2.22%

2.29%

2.08%

3.09%

3.20%

3.35%

5.83%

7.28%

3.31%

2.73%

1.88%

2.64%

3.64%

3.78%

3.18%

2.24%

1.41%

100.00%

%

OF

TOTAL

D

3.70%

2.46%

4.61%

16.19%

2.24%

$

DIFFERENCE

%

DIFFERENCE

E

$7,295.04

$372.17

-$14,452.86

$11,848.49

-$17,153.01

F

149.70%

4.81%

-50.47%

28.60%

-69.99%

$4,912.25

-$2,300.24

-$2,545.24

$8,667.05

$2,325.80

$1,713.14

-$3,562.67

$4,525.68

$8,124.13

$1,762.92

$8,662.86

$5,579.50

$3,294.75

-$146.48

-$3,520.57

-$913.82

87.61%

-17.28%

-11.72%

56.68%

27.17%

-16.03%

-36.60%

108.75%

121.47%

49.43%

144.58%

38.71%

82.09%

-1.90%

-34.02%

-8.26%

-$21,341.10

-$3,734.60

-$347.14

$3,886.22

-64.03%

-23.09%

-3.21%

111.90%

$1,474.00

46.48%

112 Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002

Conclusions

Percentage Based Allocation has been tried and found workable at a large academic research library. It has been used by SUNY

Stony Brook since 1994. Stony Brook’s implementation of PBA was tempered by local circumstances. The acquisitions budget was flat from 1990/91 to 1995/96 and since

1995/96 any inflationary increases have been used to increase the allocation for access (electronic resources). Thus the

Libraries lacked the additional funds necessary to correct imbalances in the allocations without taking funds away from some academic department. Although political realities and lack of financial resources prevented the immediate implementation of a pure and unmodified

PBA, the framework for a rational allocation of the materials budget was put in place and progress has made toward equitable distribution each year.

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Washburn is just beginning to test whether

PBA is a useful tool for a small to medium sized academic library. Obstacles to PBA at

Washburn are the reluctance to change a long established allocation formula and the difficulty in obtaining accurate statistics on the periodicals budget (both spending per subject and the actual amount spent on periodicals, excluding prepayments, in a fiscal year). Although Genaway originally proposed PBA for small to mid-sized colleges, the preliminary Washburn PBA shows greater discrepancies than the early

PBA at Stony Brook. Does this suggest that

PBA may in fact be more suited to large academic research libraries or are Washburn and Stony Brook unique examples? More research, including replication of PBA at other libraries, is needed.

References

Brownson, Charles W (1991) “Modeling Library Materials Expenditure: Initial Experiments at

Arizona State University,” Library Resources and Technical Services 35/1 (January),

87-103.

Budd, John M (1991) “Allocation Formulas in the Literature: A Review,” Library Acquisitions:

Practice and Theory 15, 95-107.

Budd, John M and Adams, Kay (1989) “Allocation Formulas in Practice,” LibraryAcquisitions:

Practice and Theory 13/4, 382-390.

Cubberley, Carol (1993) “Allocating the Materials Funds Using Total Cost of Materials, J ournal of Academic Librarianship 19/1, 16-21.

Genaway, David C (1986a) “PBA: Percentage Based Allocation for Acquisitions: A Simplified

Method for the Allocation of the Library Materials Budget,” Library Acquisitions: Practice and Theory 10, 287-292.

Genaway, David C (1986b) “The Q Formula: The Flexible Formula for Library Acquisitions in

Relation to the FTE Driven Formula,” Library Acquisitions: Practice and Theory 10,

293-306.

German, Lisa B and Schmidt, Karen A (2001) “Finding the Right Balance: Campus Involvement in the Collections Allocation Process,” Library Collections, Acquisitions & Technical

Services 25, 421-433.

Greaves, Francis Landon (1974) The Allocation Formula as a Form of Book Fund Management in Selected State Supported Academic Libraries.

Dissertation. Florida State University.

Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002 113

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Lowry, Charles B (1992) “Reconciling Pragmatism, Equity, and Need in the Formula Allocation of Book and Serial Funds,” College and Research Libraries 53/2 (March), 121-138.

Muller, Hans (1941) “The Management of College Library Book Budgets,” College and

Research Libraries 2 (September), 321.

Mulliner, Kent (1986) “The Acquisitions Allocations Formula at Ohio University,” Library

Acquisitions: Practice and Theory 10, 315-327.

Packer, Donna (1988) “Acquisitions Allocations: Equity, Politics, and Formulas,” Journal of

Academic Librarianship 14, 276-286.

Rein, Laura O, Hurley, Faith P, Walsh, John C and Wu, Anna C (1993) “Formula-Based Subject

Allocations: A Practical Approach,” Collection Management 17, 25-48.

Sanders, Nancy P (1983) “A Review of Selected Sources in Budgeting for Collection Managers,”

Collection Management 5, 151-159.

Schad, Jasper G (1978) “Allocating Materials Budgets in Institutions of Higher Education,”

Journal of Academic Librarianship 3/1, 328-332.

Shirk, Gary M (1984) “Allocation Formulas for Budgeting Library Materials: Science or

Procedure?” Collection Management 6, 37-47.

Shreeves, Edward, editor (1991) Guide to Budget Allocation for Information

Resources.

Collection Management and Development Guides 4. Chicago: American Library

Association.

State University of New York at Stony Brook (1998) 1997-1998 Operating Budget.

Stony

Brook: The University.

State University of New York at Stony Brook Libraries (1993a) Collection Analysis Project:

Final Report. Stony Brook, The Libraries. ERIC document ED 377 840.

State University of New York at Stony Brook Libraries (1993b) Collection Analysis Project:

Report of the Task Force on Funding and Materials Budget Allocation. Stony Brook: The

Libraries.

State University of New York at Stony Brook Libraries (1992a) Strategic Directions, 1992-1997:

A Plan for the University at Stony Brook Libraries. Stony Brook: The Libraries. ERIC document 377 841.

State University of New York at Stony Brook Libraries (1992b) Strategic Planning Task Force on Collection Development: Final Report. Stony Brook: The Libraries.

Tuten, Jane H and Jones, Beverly, comps. (1995) Allocation Formulas in Academic Libraries.

CLIP Notes 22. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Washburn University Mabee Library (2002) Collection Analysis Project: Interim Report, April

2002 . Topeka, KS: Mabee Library.

Washburn University Mabee Library (2002) Washburn University, Mabee Library, Strategic

Plan, 2000-2003. Topeka, KS: Mabee Library.

Webster, Judith D (1993) “Allocating Library Acquisitions Budgets in an Era of Declining or

Static Funding.” Journal of Library Administration 19, 57-74.

114 Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002

PBA: A Statistics-based Method to Allocate Academic Library Materials Budgets

Werking, Richard Hume (1988) “Allocating the Academic Library’s Book Budget: Historical

Perspectives and Current Reflections.” Journal of Academic Librarianship 14, 140-144.

Young, Heartsill et al (1983) The ALA Glossary of Library and Information Science. Chicago:

American Library Association.

Young, Ian (1992) “A Quantitative Comparison of Acquisitions Budget Allocation Formulas

Using a Single Institutional Setting.” Library Acquisitions: Practice and Theory 16,

229-242.

Yunker, James A and Covey, Carol G (1980) “An Optimizing Approach to the Problem of the

Interdepartmental Allocation of Library Materials Budget,” Library Acquisitions: Practice and Theory 4, 199-223.

Statistics in Practice – Measuring & Managing 2002 115