Entry to Arrest: Ramey, Payton, and Steagald

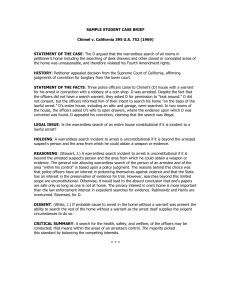

advertisement