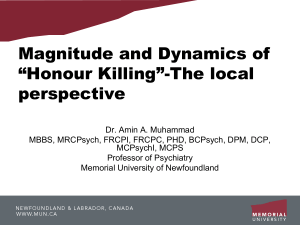

Preliminary Examination of so-called “Honour Killings” in Canada

advertisement