CPS pilot on forced marriage and so-called 'honour'

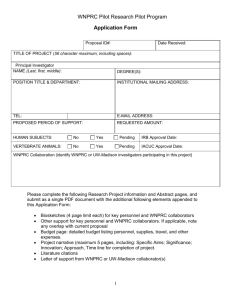

advertisement