Whiteman:Layout 1 - Werner Forman Archive

advertisement

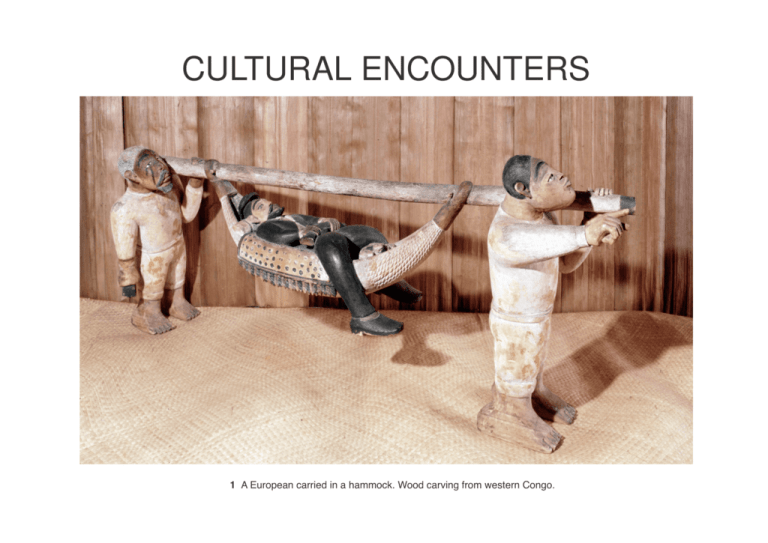

CULTURAL ENCOUNTERS 1 A European carried in a hammock. Wood carving from western Congo. In recent centuries at least, there cannot have existed a people so isolated that they had no knowledge of others. Since before Roman times, travellers had been following established cross-country trade routes through Central Asia to and from India and beyond, bringing goods which were shipped to Europe and carried south from Morocco by the great camel caravans across the Sahara to the western Sudan. Ocean voyages too have been undertaken for thousands of years. The Minoans carried on regular trade between Crete and Egypt, the Phoenicians were trading to England for tin in 600 BC and by the 10th century the Vikings were making regular expeditions to Newfoundland from their settlements in Greenland. In the east, traders from the ports of Arabia and Asia had been sailing on short-range voyages in the Indian Ocean, along the East Coast of Africa and in the Pacific since the earliest times. The idea of early explorers in the South Pacific that “We were the first that ever burst into that silent sea” was, it is generally agreed, a romantic illusion. Even if contact had not taken place, stories and very often, trade goods preceded the strangers. In around 430 BC Herodotus wrote that he had heard that north Europeans slept for six months at a time because of the insupportable cold and that they had feet of goats. More recently, in 1935, an expedition to a remote part of New Guinea came upon a hitherto unknown tribe whose headman greeted the European explorers brandishing a steel axe. Fact and fancy were very often mixed. But in the mid-l5th century, important developments in Europe led to a wave of maritime enterprise and overseas expansion which changed the world and fanciful stories of exotic white men became fact for peoples in every continent of the world. The Atlantic seaboard countries of Europe were forced, because of the Venetian and Muslim hold on international trade with Asia and Africa and in the Mediterranean, to look towards their ocean horizons. New long-range sailing techniques became available chiefly through the work of Prince Henry of Portugal, later known as Henry the Navigator (1394-1460) who, under the patronage of his brother the king, researched crucial changes in ship design and navigation skills. These innovations and inventions, along with the desire for commercial prizes, were to lead the Portuguese to venture further and further south. A number of maritime expeditions set out down the coast of Africa in search of gold and pepper, in particular. By 1445 they had reached Senegal, in 1487 they were at the Cape of Good Hope and in 1498 Vasco da Gama arrived in India. Some thirty years after Columbus, a Genoese sailor in the service of the Spanish monarchs, led the way to the discovery of a whole new continent, the “New World”. A ship commanded by Magellan, a Portuguese, completed the first voyage around the world proving that all the oceans of the world were linked. With these great voyages of discovery came new maritime skills followed by new geographical knowledge. From this time all European nations with access to the Atlantic had the opportunity to make contact with the world far beyond their shores. The first Portuguese expeditions were followed by the Spanish, the British, the French, the Danes, the Swedes and the Germans. During the course of the next two hundred years European explorers and traders made contact with Africa, the Americas, southern China, Indonesia, Australia, New Zealand and Japan. 3 An ivory salt cellar with figures of Portuguese noblemen and on its lid a ship with a crow’s nest and lookout. Nigerian. There have been several periods of European exploration and many types of stranger. Some were seen as benign, some cruel and harsh and it cannot be denied that violent and destructive crimes were perpetrated and indigenous populations suffered terribly during this long period of European expansion. But during the earliest period, following the arrival of the Portuguese on the west coast of Africa, after a certain amount of raiding and looting, relations with the coastal Africans settled down and, for a time, peaceful trading benefited all. Products highly valued in Europe such as pepper, amber, gold, ivory and indigo were traded for metal goods, cottons, silks, glass, mirrors and armour. During this early period the trade was largely one of partnership between Africans and Europeans. Representations of foreigners in Africa at this stage were few but their presence was noted at the court of Benin, on the bronze plaques on which were recorded historical events and which adorned the walls of the palace of the Oba. Merchants and dignitaries also appeared on the so-called Afro-Portuguese ivories which were made in Sierra Leone for export to the Portuguese royal court. 2 Two Portuguese males holding hands, perhaps father and son, on a brass plaque from the palace of the Benin Obas. But this first peaceful trade laid the foundations for an altogether more sinister phase of European expansion. From the 16th to the 19th century the trade in gold and in slaves dominated European interests. By the time the slave trade was abolished in 1865 between nine and ten million slaves had been sent to Europe and across the ocean to the American colonies. During this time rivalry bet-ween the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British erupted on the west African coast and today the slave castles of Elmina and Cape Coast Castle, fortresses which passed into the hands of each of these powers in turn, stand as grim monuments to an evil trade. With the abolition of slavery, the European powers became obsessed with obtaining land and raw materials. Europeans were travelling to Africa, India and the Far East in growing numbers. Civil servants, businessmen, technicians, teachers and missionaries pursued political and economic power and zealously set about the cultural and spiritual reform of the inhabitants of the countries they sought to manipulate and control. What did the indigenous peoples think of these exotic strangers? Were they awed by our dazzling technology and intelligence? We tend to flatter ourselves that that is the way it was. But nobody really bothered to ask. Some clues to the truth can be gained by studying a fascinating number of objects and works of art, all of which were created according to local tradition and all of which have a common theme – the role of the “white man” in the countries he visited and the reaction of the people he sought to dominate. Europeans can be seen being carried in hammocks in Africa, smoking hookahs in India, consorting with geishas in Japan, fighting with guns in America, and hunting in China. The physique, clothes, personalities, customs and possessions of the explorers, soldiers, 4 Elmina Castle was a major base for the slave trade. Ghana. 5 A European being driven in a car. Luba, Congo. 6 A mask representing a European wearing sun glasses, with a rum barrel on his head and a pencil behind his ear. Yoruba, Nigeria merchants, missionaries and colonial administrators have been observed and recorded. It is not possible to generalize about the meaning and function of the images for they were made by a variety of people who were subjected at different times in history and in different circumstances to European culture. The high civilizations and the so-called primitive societies each reacted differently to the presence in their countries of the “exotic white man”. In Africa, up to the mid-l9th century, colonization had not much impact on the traditional way of African life. The conflict and the 7 A white man dressed like a captain with the symbols of his power – umbrella, clock, mirror, tools, etc. A magical painted board – henta-koi – from Nicobar Islands, India. 8 Another “henta” from the Nicobars. Deuse, the white man’s god, is shown with instruments of his power. Such magical shields were kept in the home of a sick person.If the person died, the shield was discarded. In Africa, up to the mid-l9th century, colonization had not much impact on the traditional way of African life. The conflict and the harm arose when Europeans occupying the land sought to impose systems of law and government without taking into account tribal and group customs. By 1912, Europe had colonised the whole of Africa except Ethiopia and Liberia and when the First World War broke out Africa was divided up between the British, French, Germans, Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese and Belgians. Between the white man and the vanquished population there existed a state of complete incomprehension. One need not look beyond the records of the brutally oppressive regimes for the reason why, in the masked spectacles of the Yoruba people of Nigeria when the role called for a character that was despicable, avaricious or rapacious, does the mask represent a white man. The shrine figures representing Europeans cannot be said to be gods but rather an attempt to represent authority. “Pay attention or I will call the white man!” mothers would threaten their children. Sometimes the white man is represented merely as a figure of fun. It seemed that the newcomers came from a land of infinite wealth. Images of his omnipotence abound. The “white chiefs”, Edward Vll and Queen Victoria of England and Wilhelm II of Germany, have been portrayed and guns, chairs, bicycles, motor cars, hurricane lamps, sewing machines and other icons of the white man were made, some to be used in healing cults and as shrine objects, or simply to be sold to Europeans. Nor was it possible for the peoples of the Pacific to ignore the white man’s power. The newcomers were welcomed as returning ancestors who brought with them many desirable objects. When the “dead” did not continue to provide this “cargo” in unlimited quantities the people established religious cults whose followers believed that spiritual agents would deliver the sought-after manufactured goods into their hands. Europeans first arrived among the Indians of the northwest coast of America to trade for furs. Already there existed a great tradition of wood and argillite carving but, in the early days of contact, these works were rarely sold. When the use of tobacco was 9 A red-headed sailor or trader whose freckles have been inlaid in glass. Haida culture, Northwest coast of America. 10 A ship’s figurehead in miniature, from an American Indian tobacco pipe. Haida culture, Northwest coast of America. adopted by the people of the northwest coast, figures of white men began to appear on finely carved smoking pipes. From the middle of the 19th century, when the trade in furs was declining due to over-hunting, figures of Europeans, particularly of sailors and their ships, were made as souvenirs and sold to supplement the dwindling number of items that were available for trade. Mediterranean markets had obtained luxuries from India via overland trade routes long before the arrival by sea of the Portuguese in 1498. After the Portuguese came the Dutch, the French and the English, all pursuing commercial interests. In the first centuries 11 Portuguese or other European naval mercenaries in India. Late 16th century. 12 Sir David Ochterlony, Resident at the court of the Great Mogul in Delhi, wearing Indian dress and smoking a hookah, is treated to an entertainment. 18th century. 13 A Dutch merchant and his family attended by their Indian servant. Late 17th century. 14 An official of the East India Company enjoying a water-pipe, attended by servants. c. 1769. of their presence in India, Europeans hardly had much effect on Indian artistic culture. In the 16th century, painters at the court of Akbar occasionally recorded the presence of the foreigners and later, textiles made for the European market combined designs of Indian motifs with figures of Portuguese and Dutch merchants and their families. Officers of the 18th century East India Company lived much in the style of Indian gentlemen, some of them taking to Indian dress and food and some took Indian wives. Gradually more Englishmen began to live in India and make their careers there. They and their wives lived more and more apart and became more and more convinced of their superiority. They commissioned souvenir paintings and as they acquired political strength they had their portraits painted by Mughal painters in a manner which they considered emphasized their power and prestige. The mandarins of ancient China looked upon their country as the centre of the world – everybody not from the “Middle Kingdom” was looked down upon. Unlike Japan, China had long been in contact with peoples to the west. Numerous tomb figures dating from the Tang dynasty (AD 618–906) which depict western and central Asians bear witness as to how the foreign traders were seen. The stereotype image is of a wild man with curly hair, bulging eyes, flaring nostrils, moustache and beard. With the arrival of the Portuguese in China around 1514, the Chinese, with their long tradition of producing wares for export to other Asian states via the Silk Route, began making a wide range of articles to suit the demands of the new customers in Europe. During the 18th century, 15 A Portuguese carrack at Nagasaki depicted on a Japanese folding screen. 17th century. 16 A Dutch ship’s boy blowing a trumpet. Made in Nagasaki in early 18th century. 17 Portrait of a Danish seaman made in Canton in 1731. 20 A Chinese stereotype of a foreigner: Western Asian trader with a flask has curly hair, flaring nostrils, bulging eyes and moustache. T’ang dynasty, 518–906 AD. 18 Two Jesuits depicted on a Japanese folding screen. Early 17th century. 19 European tea merchants at a tea auction in a Hong Kong warehouse. c. 1800. 21 Chinese view of a European lady rider. 22 Russian and French vessels off Yokohama. 1861, Japanese print. 23 Russian admiral Putyatin arrived in Japan in 1853 to negotiate a treaty which was eventually concluded in 1854 . His squadron lay at anchor off Nagasaki for three months. Japanese print. the craze in France and England for Chinese wares reached its height but apart from the export of porcelain and furniture which supplemented the trade in tea, silk, and drugs, the Chinese showed little interest in portraying Europeans and when they did it was for the export market. The first Europeans to arrive in Japan were the Portuguese in 1542–3 and St Francis Xavier and his missionary priests followed in 1549. Japanese magnates tolerated their presence and in 1570 Nagasaki, then a village, was opened to foreigners. Trade brought the Dutch, Spanish and the English but this first period of western contact with Japan ended in the 18th century with the expulsion of all but a few Dutch tradesmen who were allowed to trade from a station on Deshima Island in Nagasaki harbour. This state of affairs remained until the mid-l9th century when Europeans began to show a renewed interest in trading with Asia. A US naval officer, Commodore Perry was commissioned by his president to begin negotiations and in 1853 ships under his command sailed into Edo Bay. Treaties were signed and Russia as well as other trading nations arrived. These developments have been recorded in graphic detail in many woodblock prints, lacquer screens and art objects and from these it can be seen how bizarre the Japanese found the dress, belongings and custom of the foreigners. The “southern barbarians”, as Europeans were first known, were portrayed as grotesques with big noses and facial hair. Later, during the period of renewed contact in the 19th century, the “red-haired people” once again became objects of intense scrutiny and the vivid detail of the portrayals show the fascination these exotics held for the Japanese. To look at ourselves from another point of view can be a salutary experience. One Native American expressed his opinion thus: “Who can understand the whiteman? What makes him tick? How does he think and why does he think the way he does? Why does he talk so much? Why does he say one thing and mean another? Most important of all, how do you deal with him? Obviously he is here to stay. Sometimes it seems like a hopeless task.” (1) Paul Gauguin, writing of his sojourn in Tahiti, noted: “Above all, they have taught me to understand myself better. I have heard nothing from them but the most profound truth.” 1. from Keith Basso Portraits of the Whiteman - Linguistic Play and Cultural Symbols among the Western Apache. Cambridge University Press, 1979. Text © 2005 Barbara Heller, Illustrations © 2005 Werner Forman Archive 24 A shy Japanese girl serves saké to a coarse bearded foreign sailor. OWNERS OF OBJECTS PHOTOGRAPHED BY WERNER FORMAN: 1 Museum voor Land en Volkenkunde, Rotterdam; 2, 7, 8, 11, 16 British Museum, London; 3 Entwistle Gallery, London; 5 Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale, Tervuren; 6 H. Storrer Collection; 9 Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska; 10, 19 Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts; 12 India Office Library, London; 13 Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris; 14 Victoria and Albert Museum, London; 15 Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo; 17 Handels-og-søfarts museet, Slog Kronborg, Denmark; 18 De Young Museum, San Francisco, California; 21 C. D. Wertheim Collection