Wilderness and Social Reform in Herman Melville's The Piazza

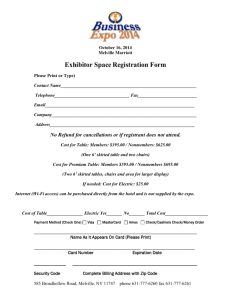

advertisement

"I' l1 Sweeten Thy Sad Grave":

Wilderness and Social Reform in Herman Melville's The Piazza Tales

by

Molly Mande

A thesis submitted to

Sonoma State University

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of

MASTERS OF ARTS

in

English

Dr. Kim Hester-Williams, Chair

Dr. Timothy Wandling

I

I

Date

Copyright 2013

By Molly Mande

11

Authorization for Reproduction of Master's Thesis (or Project)

I grant permission for the print or digital reproduction of this thesis in its

entirety, without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or

agency requesting reproduction absorb the cost and provide proper acknowledgment of

authorship.

Signai&e*

Ill

"I'll Sweeten Thy Sad Grave": Wilderness and Social Reform in Herman Melville's

The Piazza Tales

Thesis by

Molly Mande

ABSTRACT

This thesis explores how Herman Melville's depiction of the relationship between Man

and Wilderness in his collection of short stories, The Piazza Tales, critiques the social

reform movements of the mid-nineteenth century. By highlighting how Melville's

portrayal of the relationship between Man and Wilderness parallels that seen in Early

American survey writing texts such as Notes on the State of Virginia as well as midnineteenth century nature writing texts such as Walden, this thesis asserts that Melville is

showing how the evolution of the relationship between Man and Wilderness retains an

inherent level of subjugation. Similarly, by showing how Melville's text parallels the

relationship between Man and Wilderness with that of Man and subjugated Man, this

thesis suggests that Melville was making a claim that, due to the inherent subjugation that

exists within the American social structure, the social reform movements of the mid-19th

century would, ultimately, be ineffective-a reality which is apparent in the persistence

of social, racial, and economical stratification in early 21st century America.

Chapter 1 synthesizes G.W.F. Hegel's Master-Slave Dialectic and Bill Brown's "Thing

Theory" in order to demonstrate how Melville's depiction of the relationship between

Man and Wilderness mirrors the relationship between Man and Subjugated Man. Chapter

2 explores the parallels between Thomas Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia,

Melville's depiction of the relationship between Man and Wilderness in "The Piazza,"

"The Lightning Rod Man," "The Encantadas," and "The Belltower," and the treatment of

subjugated peoples in pre-Westward Movement America. Chapter 3 examines how

Melville's portrayal of the relationship between Man and Wilderness in "The Piazza,"

"The Lightening Rod Man," "The Belltower," and "Bartleby the Scrivener" imitates that

of mid-nineteenth-century America

Signature

MA Program: English

Sonoma State University

iv

·Acknowledgements

A sincere and humble thanks to everyone who has encouraged me, pushed me, and held

my hand throughout my Masters program and throughout the process of writing this

thesis, especially:

To my family, for their unconditional love, support, and for understanding when I forget

to call.

To the amazing ladies of my cohort, for constantly inspiring me with friendship as well as

scholarship.

To Toby, for being there with affection, understanding, and bourbon during my moments

of success and my moments of crisis.

To Thaine Steams and John Kunat, for pushing me into the deep end and making me

realize I could swim-metaphorically.

To Scott Miller and Mira-Lisa Katz, for showing me scholarship can be empathetic and

unique.

To Tim Wandling, for following and encouraging my ever-evolving thesis topic.

To Kim Hester-Williams, for giving me my first breath of fresh air that is American

Literature, and for constant and unwavering support, enthusiasm, feedback, and handholding throughout the distance-sport that has been my writing process.

And finally, to Herman Melville who gave me a path to his heart, his mind, and his world

through the seemingly endless literary labyrinth that is The Piazza Tales.

v

Table of Contents

Section

Page

Introduction ................................................................................................ 1

Chapter I. ........................................................................................................................14

Chapter IL ................................................................................................................... 30

Chapter III. ............................................................................................ 42

Conclusion........................................................................................................................ 56

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................... 5

Vl

Introduction

"Jn these times offailingfaith and feeble knees, we

have the piazza and the pew "

"The Piazza"

Herman's Melville's collection of short stories, The Piazza Tales, is unique not

only because it is the only collection of his short stories to be published during his

lifetime, but also because it appears to represent a shift in focus and intent for the writer.

Melville's early works, such as Typee and Omoo, were well-received travel-fiction

novels, which explored the exotic worlds of the Pacific Islands he had encountered as a

sailor. His next few novels, Mardi, Whitejacket, Redburn, and Moby Dick-which also

took place at sea but were significantly more philosophical and symbol-ladened-were

not nearly so well received. Melville's frustration with his novels' lack of success was

particularly apparent in response to the minimal popularity of Moby Dick which,

compared to Whitejacket and Redburn, "two jobs which [he had] done for money," he

thought of as his masterpiece. Thus, by the time he wrote the short story, "The Piazza,"

and published the collection of stories in, The Piazza Tales, Melville was frustrated that

the novels he, and some critics, felt were monumentally better writing, were so poorly

received. However, despite the diminishing popularity of his works, Melville refused to

return to writing travel-fiction, but instead continued to write fiction that was increasingly

symbolic and heavily critical of American social structures. In "The Piazza," the title

story of The Piazza Tales, the narrator, who has journeyed into the surrounding

countryside in search of a Shakespearian fairy kingdom, states he will be "launching [his]

yawl no more for fairyland" (12). While the narrator is referencing his choice to no

2

longer seek a fantastical existence, the statement also reads as a declaration by Melville

to himself and to his readership. While the narrator journeys "no more for fairyland,"

Melville is announcing to his readers that, despite their popularity, he will produce no

more travel stories about exotic lands. Instead, he will continue to do the kind of writing

he thinks to be worthwhile: works that are complex, subversive, and focus on the plights

of America-specifically, in The Piazza Tales, social reform. In addition, the narrator's

statement can be read as a lament of Melville's own loss of optimism. Since the narrator

of "The Piazza" believes himself to be journeying to "fairy-land," and to the shining

house on the hill, his declaration that he will no longer "journey to fairy-land" can be

read as the result of realizing that there is no fairy-land-just the same reality as his own,

but further away. Considering the point in Melville's career that "The Piazza" was

written, this loss of optimistic fantasy likely mirrored his state of mind, as well as that of

the narrator. For Melville, no longer journeying "to fairy-land" alludes to his

determination not to succumb to pressures from publishers and his readership to return to

writing about the fantastical lands he encountered while at sea, as well as to no longer

holding on to the belief that his work would be appreciated for its depth, complexity, and

philosophical exploration of the American social structures.

This is not the only occurrence of Melville's voice and persona appearing within

one of his characters in The Piazza Tales. While not overt, the autobiographical elements,

which are scattered throughout the collection, serve to ground The Piazza Tales in

Melville's contemporary America, which allows the reader to draw numerous parallels

between the tales and many social issues that were ubiquitous in Pre-Civil War

America-especially those that directly affected Melville. For example, "Bartleby the

3

Scrivener," which was previously published in Putnam's in 1853 is often considered to

be about Melville's own frustrations with how the industrialization of the workforce was

changing the business of writing. Similarly, both "Benito Cereno" and "The Encantadas"

deal with the social hierarchy of a ship, which Melville, who spent many years on a

whaling ship, had vast experience with. In fact, many of Melville's critiques of social

inequality are thought to have originated with the social hierarchy he witnessed while

under way. Most specifically, according to Andrew Delbanco, Melville was wary of how

"human beings organize themselves into ranks, and how those doing the organizing

always reserve a place for themselves at the top" (157). As for "The Piazza," according to

Biographer Hershel Parker, it was "a celebration of Melville's own piazza" and The

Piazza Tales were "'written on a piazza which command[ed] a grand view northward to

[Mt.] Greylock'" (164, 273). The significance of Melville's presence in "The Piazza"which is often thought to act as a key to the collection-is that by paralleling himself

with the narrator of 'The Piazza,' Melville draws a connection between his 'view'-that

of an America which is attempting to reform its social structure in hopes of a 'truer'

democracy-and the narrator's view-the wilderness.

The Piazza Tales, published in 1856, was originally set to contain five stories:

"Benito Cereno," "Bartleby the Scrivener," ''The Encantadas," "The Lightening-Rod

Man," and "The Belltower"-all previously published in Putnam 's Magazine between

the years of 1851-1855. Originally, this five-work collection was to be titled Benito

Cerino and Other Sketches. However, the title story, "Benito Cereno," would prove a

slight complication for Melville. According to Parker's extensive biography of Melville,

Pictor, a correspondent for the Evening Post, wrote an editorial titled "The Origin of

4

Melville's 'Benito Cereno"' in which he strove to inform all of New York that "Benito

Cereno" was "founded on an incident in Amasa Delano's Voyages and Travels" and to

fill readers in on "how the story was going to end" (272). As a result, and perhaps at the

urging of his publishers, Melville decided he would include a note that would append

'Benito Cereno' and give credit to Delano. However, Melville's decision to include his

note with 'Benito Cereno' changed in early 1856 when, due to his publishers pushing him

for a new story to include in the collection, Melville composed "The Piazza." Upon

completion, Melville wrote to his publishers Dix & Edwards to let them know he would

be including "The Piazza" and changing the title to The Piazza Tales. In this letter, he

also stated that since "the book [was] now to be published as a collection of 'Tales,"' the

appended note was, "unsuitable [and] had better be omitted" (Parker 275). Through the

addition of"The Piazza," and the subsequent shift in the title, Melville's collection

gained a new layer of meaning, which rendered the note appended to "Benito Cereno"

unnecessary.

Melville's emphasis on the shift to a "collection of 'Tales,"' in his letter to his

publishers, indicates several things that are important to deciphering this new layer of

meaning within The Piazza Tales (Sealts 56). First, that Melville believed there was an

important difference between the words 'Sketches' and 'Tales.' The Oxford English

Dictionary defines 'tale' as both "a story or narrative, true or fictitious," as well as "a

mere story, as opposed to a narrative or fact," while 'sketch' is defined as "a brief

account, description, or narrative giving the main or important facts. " 1 Thus, the word

'tale' holds connotations of both truth and fiction, while 'sketch' indicates a story that is

1

"tale, n." The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online., Oxford University Press. 21 February 2013

<http://dictionary .oedcom/>, "sketch, n." The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed 1989. OED Online., Oxford University Press. 21

February, 2013.

5

based on 'facts.' For Melville to determine the appended note was no longer suitable,

once the title of the collection had changed, suggests that his definition of 'tales' includes

that of a work of fiction, and, thus, does not require a citation of Delano's Voyages and

Travels as the origin of 'Benito Cereno.' Secondly, Melville's deliberate use of the word

"Tales" in the title of his collection also hints at his larger project If, as OED states,

'~tales"

refers to stories that are either "true or fictitious," Melville is bringing the truth

and fiction of each story into question through the very title The Piazza Tales. While in

the case of "Benito Cereno," the term 'tale' in the title may serve to highlight its fictitious

state; for the five other works, it also serves to bring into question the 'truth' of each tale.

As previously mentioned, ''The Piazza," "Benito Cereno," "The Encantadas," and

"Bartleby the Scrivener" can easily be read as allusions to Melville's own experiences.

However, each of these stories also contains elements that diverge from Melville's life.

For example, although ''The Piazza" might be "a celebration of Melville's own piazza,

the narrator of 'The Piazza' is also portrayed as processing a Thoreau-esque

transcendentalist approach to the surrounding wildemess---an ideology of which Melville

was a known skeptic (Parker 164). Similarly, 'Benito Cereno,' may be based on a true

occurrence, but Melville's "tale" is actually a greatly embellished fictive account, which

bears only a skeletal resemblance to Delano's original account. By allowing these tales

to resemble real-life situations---or "sketches"-while still being "tales," Melville is

blurring the line between fact and fiction and, thus, bringing the very divide between fact

and fiction-or reality and illusion-into question.

There are, in fact, many elements in 'The Piazza,' which bring reality in question

and make Melville's story, according to Parker, a "meditation on illusion and truth"

6

(273). One example is the epigraph, which is a quote from Shakespeare's Cymbeline. The

epigraph reads: "with fairest flowers/whilst summer lasts and I live here, Fidele-" ( 1).

While at first read this quote may appear to relate to 'The Piazza' because of its mention

of nature ('flowers,' 'summer'), the odd choice to leave the name, 'Fidele,' at the end

hints that the quote is being utilized for some other veiled meaning. In Cymbe/ine, Fidele

is the name taken on by Imogen, the daughter of the king of Brittan, when she flees her

home, disguised as a boy (Shakespeare 1199). At this point in Shakespeare's play,

Imogen is the target of many false accusations and assumptions: her love, Posthamus, has

accused her of infidelity because of a lie told by Posthamus' friend; she has taken on the

persona (and attire) of a boy, Fidele, in order to flee her kingdom; and she is, at the time

the quote is spoken to her, presumed to be dead because she has taken poison, which she

believes to be medicine. The speaker of the quote believes that Imogen is a boy, Fidele,

and that 'he' is dead. Thus, under the surface of this quote, are many layers of uncertain

reality and false perception. Melville was known to be an avid admirer and reader of

Shakespeare's works, and according to F.O. Matthiessen, author of American

Renaissance, had "[gone] through the whole of Shakespeare in the winter of 1849" (412).

Melville would have been thoroughly aware of the depth of meaning behind his

Shakespeare epigraph, and thus his choice to preface 'The Piazza' with it is a strong

indication of his desire to bring reality and perception into question in 'The Piazza. ' 2

Matthiessen also draws a connection between Melville's interest in Shakespeare

and Melville's desire to explore the division between reality and perception. According

to Matthiessen, "in [Melville's] examination of both society and religion he became

2

Among various proofs of Melville's admiration of Shakespeare is a painting, which Melville had in is collection, which Andrew

Delbanco includes in his Biography of Melville, Melville: His World and His Work. The painting is of"Cymbaline, Act 2, Scene 2:

'A bed chamber; Imogen in Bed."'

7

increasingly possessed by Hamlet's problem," which is "the difference between what

seems and what is" (376). The examination of this dlfference manifests throughout "The

Piazza" The narrator, in recounting his 'journey into fairy-land,' refers to it as "a true

voyage; but. .. interesting as if invented" and, after his return, he laments how he is

"haunted by Marianna's face, and many as real a story" (4, 12). In both of these

statements, Melville's use of the word 'as' serves to make the statements conditional and,

thus, leave the reader unsure whether the narrator's journey actually transpired, or if it

was imagined by him. This decentering of 'reality' becomes all the more complex due to

the juxtaposition with the narrator's own constructed reality. On one side is what, at first,

appears to be a fairly straightforward and undisputable reality: the narrator decides to

hike up a mountain, finds a decrepit house, talks to the girl who lives there, and comes

home. On the other side is the fantastical world the narrator paints through constant

allusions to fictional and allegorical works and characters as well as lamentations on the

subliminal beauty of the surrounding wilderness. For example, the narrator's description

of the surrounding wilderness includes references to a sky which holds "Orion" and his

"Democles' sword," and can be as "ominous as Hecate's cauldron"; mountains which are

"Charlamaigne" and "his peers," who "play at hide-and-seek"; a meadow where

"Macbeth and foreboding Banquo" walk; and a path to fairy-land along which the

narrator finds "Eve's Apples," and a ring where "fairies must have danced" (2, 4, 7). By

describing his world through these fanciful elements, the narrator creates a sense of

division between the reality of his world-he lives in a farmhouse, goes on a hike, and

meets a girl who lives on an adjacent mountain--and how he chooses to view the

world-he lives in a magical land surrounded by literary, mythical, and biblical

8

characters, and journeyed to fairy-land. However, because that which appears to be

reality (the 'journey,' Marianna) is later brought into question, it is suddenly the

constructed reality of the narrator that maintains a sense of stability and, thus, reality. 3

Further complicating the issue of reality in 'The Piazza' is the fact that the literary

references the narrator uses are predominately of European origin: A Midsummer's

Nights Dream, Hamlet, Macbeth, and Cymbeline by William Shakespeare, The Faerie

Queene by Edmund Spencer, and Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. Considering

these references are the basis upon which he builds his constructed reality, they can be

considered crucial points of reference for his sense of reality. However, because these

stories are of European origin, the narrator is essentially overlaying a reality of European

origin upon an American landscape. While the envisioning of European literary

characters in an American wilderness may not seem problematic, it is actually

symptomatic of a larger ideological problem. Scott A. Kemp, author of"'They But

Reflect the Things': Style and Rhetorical Purpose in Melville's 'The Piazza Tale,'(sic)"

suggests that "['The Piazza'] critiques an America that had failed to overturn Old World

abuses and implement lasting republican reform" (60). Kemp's claim is further supported

by Thomas Jefferson's survey text, Notes on the State o/Virginia, where Jefferson

discusses how "The common law of England" was "made the basis" of the laws and

codes of the newly established Commonwealth of Virginia (144). Although the

democratic model of American politics boasted a divergence from Britain's Monarchy, it

3

Although it post-dares Melville, the mechanics of this juxtaposition can be explained by Jean Baudrillard's Simulacra and

Simulation. In his theoretical rext, Baudrillard discusses how what we rend to look at as ''the real" is only real in contrast to what we

see as the unreal. He gives the example of Disneyland in contrast to the surrounding Los Angeles metropolitan area. Disneyland is a

self-identified figurehead of the unreal. It is an intentionally construcred hyperfantastical. reality. However, because people look to

Disneyland as an example of non-reality, Los Angeles, which is in no way a model ofreality, seems "real." Similarly, in contrastto

the narrator of "The Piazza"' s augmenred reality, there is no reason to doubt the reality of the journey he goes on. However, once the

reality of that journey is brought into question, it is suddenly the fantastical world he has painted which retains the greater sense of

reality. Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 1994. Print.

9

can be inferred from Jefferson's statement that much in the way of laws and political

structure was actually modeled on English law. Considering the potential conflict

between the separation from British rule and the emulation of British rule, the fact that

the narrator of "The Piazza" overlays his American landscape with European fantasy

models to create his fantastical reality, seems to be Melville implying that America's

democracy was overlaid by European ideology and social structures. This concern of the

division between how American democracy was perceived, and the ways in which it was

simply perpetuating age-old social systems, appears to be a concept Melville struggled

with, and one he explores deeply throughout The Piazza Tales.

Melville's exploration and criticism of American social reform did not begin with

The Piazza Tales. Even his early works of travel-fiction, under the pretense of exposing

readers to the exotic world of the Pacific Isles, were, according to David S. Reynolds,

author of Beneath the American Renaissance, "protest[s] against mainstream

Christianity" and "missionaries on the South Sea Islands" as well as "subversive

commentary on the norms and values of white civilization" (137). However, in The

Piazza Tales, Melville's critique of American social reform seems to be situated in a

place of personal proximity, involvement, and consequence that his prior works were not

In the years leading up to and during Melville's work on The Piazza Tales, he found

himself increasingly involved and affected by the shifts in the social and labor

movements. Melville's father-in-law, Judge Shaw was pivotal to setting and enforcing

the standards of the Fugitive Slave law when he, despite his own personal beliefs that

slavery was "abhorrent," "declined to affirm the unconstitutionality of the Fugitive Slave

Law" (Delbanco 154). Through his father-in-law, Melville saw how personal ideologies

10

about social atrocities were no match for a structure that already favored one class over

another. In addition, Melville, unlike many of his contemporaries, was caught between

his own feelings of apprehension and shame in regards to American slavery, and his

direct link to the enforcement of slavery. According to Carolyn L. Karcher, author of

Shadow Over the Promised Land: Slavery, Race and Violence in Melville's America,

Melville was unable to "openly attack racism and the federal government's policy of

buttressing slavery" because "he would have had to brave not merely public opprobrium,

but the reproaches of a betrayed mentor"-his father-in-law who had helped to fund and

support Melville and his family after Melville's father's death (10). However, for

Melville, slavery was not the only locus of American social discord. His own

professional and financial struggles led to a skepticism about the ways industrialization

was changing labor and had, according to John Evelev, author of Tolerable

Entertainment, "begun to undermine the artisan systems ... replacing its vocational

structures of 'trade' and 'calling' with unskilled and disadvantageous 'job' or 'piece'

work that offered little or no possibility of upward mobility" (ix). Because

industrialization privileged efficiency and quantity of output, it shifted the employment

model away from individual skilled craftsmen to a large, faceless, unskilled workforce

who were often paid poorly and forced to work long hours. In other words, in mid-to-late

nineteenth century there was a shift from chattel slavery to "wage" slavery. Although

Melville was never forced to work a factory job, shortly before he published The Piazza

Tales, he found himself frequently under pressure from his publishers to produce piece

after piece-much like in a factory assembly line-rather than being valued for

producing quality work. In fact, it is likely that this shift was responsible for impeding his

11

success as an author, and these concerns about the affect the industrial workforce was

having on personal liberty-a narrative which persist throughout the narrative of

"Bartleby the Scrivener"-suggests that it is speaking to Melville's own anxieties and

skepticism.

The strongest support for The Piazza Tales being representative of Melville's

personal experience in American social reform lies in his choice of title. In "The Piazza"

the narrator chooses to build a piazza from which he can observe the surrounding

wilderness without being affected by it. Although he does venture out into the world, by

the end of the story he has chosen to "stick to the piazza" because it is his "royal box" his

"amphitheatre" (12). Much in the same way, The Piazza Tales operate as Melville's

piazza. He is able to view, and even examine, the landscape of Pre-Civil War America

from the removed space of his writing. Although the same could be said about much of

his work, Melville's choice to title the collection The Piazza Tales indicates that not only

are they a collection of tales which are brought together by the themes they share with the

title story, "The Piazza," but they are, themselves, Melville's piazza. The further

significance of this parallel is in how it strongly aligns Melville's America with the

narrator's wilderness, and, thus, reveals the dominant argument of The Piazza Tales.

Where in "The Piazza" it is the wilderness that the narrator views and explores from his

piazza, in The Piazza Tales it is the various problematic elements of American Social

reform that Melville is exploring. Thus, by looking at The Piazza Tales as Melville's

piazza, a seemingly deliberate narrative equivalency is drawn between social reform and

wilderness.

12

This equivalency is reinforced by a common philosophical standpoint, which

appears in how Melville portrays relationships between both Man versus Man as well as

Man versus Wilderness. This philosophical framework is that of Gennan theorist G. W.F.

Hegel, which, in short, details the intricacies, and complexities in a relationship between

a master and a slave or, in his tenninology, a "lord" and a "bondsman" (115). Hegel's

theory is most readily apparent in the fonner title story, 'Benito Cereno,' which Sterling

Stuckey, whose essay 'Tambourine in Glory' appears in the Cambridge Companion to

Herman Melville, refers to as "the finest expression in literature of [Hegel's master-slave]

relationship" (55). Because this story deals with slavery, it also provides a clear example

of how Hegel's theory speaks to the history of subjugated peoples in America. However,

Melville's treatment of wilderness in

~The

Piazza,' as well as the other five Piazza Tales,

also emulates the Hegelian Master/Slave relationship by showing the various ways in

which wilderness was dominated, as well as the ways in which it was never truly

mastered. Thus, through showing how the Hegelian Master/Slave relationship exists in

both Man versus Man and Man versus Wilderness relationships, Melville begins to draw

a parallel between the subjugation of men and the subjugation of wilderness in America.

Throughout The Piazza Tales, Melville also shows the ways in which the

Hegelian Master/Slave relationship, and the evolution of that relationship, has penneated

the history of America. For example, 'The Encantadas,' satirizes how early American

survey writers, such as Thomas Jefferson, related to Wilderness in an effort to understand

and dominate it, and 'The Piazza' shows how the Transcendentalist reverence of

wilderness is also a fonn of dominating wilderness. The significance of Melville's

portrayal of this evolution of the relationship between Man and Wilderness in America is

13

that while the relationship between Man and Wilderness has significantly evolved, the

relationship between Man and Man has yet to evolve. However, the social reform

movements-such as abolition, and labor reform-are proof that America was, in 1856,

standing on the brink of social evolution.

Thus, I argue that through the parallel that is drawn between wilderness and social

reform in The Piazza Tales-especially between wilderness and slavery, Melville is

prophesizing the fate of a post-social reform America. By means of his clear allusions to

Hegel throughout The Piazza Tales, Melville shows how outwardly violent and

dominating Man/Wilderness relationships and seemingly benign Man/Wilderness

relationships are both still relationships where man subjugates wilderness. Furthermore,

by demonstrating the parallels between the outwardly violent relationship to Wilderness,

and the outwardly violent relationship to subjugated peoples, such as chattel slaves,

Melville situates Wilderness as analogous to subjugated peoples. Therefore, by

illustrating how the seemingly more benign treatment of Wilderness in mid-nineteenth

century America is, in fact, still a form of subjugation, Melville is also suggesting that

even if treatment of subjugated peoples becomes more benign, it will likely also continue

to be a form of subjugation. In this way, through his depiction of these two distinct

relationships between man and wilderness, Melville suggests that even a post socialreform America will still be subject to a social structure that, according to Hegel, is made

up of'Lords' and 'Bondsmen.'

14

Chapter 1

" ... on. where a huge, cross-grain block, fern-bedded,

showed where, in forgotten times man after man had tried

to split it, but lost his wedges for his pains-which wedges

yet rusted in their holes"

"The Piazza"

Melville's inspiration for "Benito Cereno"-which is about a rebellion on a slave

ship-can be easily, and often is, attributed to the pre-Civil war anxieties about slave

uprisings. However, considering Melville's penchant for subversive and complex fiction,

which often tackled social issues under the surface of the narrative, it is unlikely that his

inspiration would be so overt as the very thing the story is about. Just as his early travel

fiction actually took on the Christian missionaries, and Moby Dick was a commentary on

slavery, "Benito Cereno" discusses much more than just the potential hazards of the slave

trade. Many have theorized that when he wrote "Benito Cereno" Melville was thinking of

German philosopher and theorist G.F.W. Hegel's work Phenomenology ofSpirit. Hegel's

theory, which is commonly referred to as "the master-slave dialectic," explores the

complexities of dominate/subordinate relationships. Considering "Benito Cereno" is

about the relationship dynamics between slaves and the crew of the slave ship, it's no

surprise that, as Melville scholar Sterling Stuckey states, "the Hegelian echo ... is

deafening" (54). While Stuckey's claim was merely a theory at the time he made it, there

is now solid evidence that he was correct. According to Melville's own journals, on

October 21st, 1849, during a rainy night in Newfoundland, Melville and his friends,

"Adler and Taylor" discussed "Hegel, Schlegel, Kant [etc.] ... under the influence of the

whiskey" (8). The knowledge that Melville had read and discussed Hegel's theories

15

several years before writing "Benito Cereno," as well as the clear similarities between the

relationship dynamics in "Benito Cereno" and Hegel's theories, points almost defmitively

to the conclusion that "Benito Cereno was, in fact, strongly influenced by Hegel.

However, "Benito Cereno" is not the only one ofMelville's tales that features Hegel's

master-slave dialectic. All six of the stories in The Piazza Tales contain relationships that

mirror the relationship described in Hegel's text. Furthermore, this persistent presence of

Hegel throughout The Piazza Tales suggests an intentional paralleling of these

relationships. Through the frequent occurrence of Hegelian relationships, Melville's

words equates overt master-slave relationships with relationships that would likely not be

thought of as master-slave relationships. The result of this equivalency is a touchstone

definition of subjugation-a definition that equates all Hegelian relationships with

slavery. Thus, by utilizing Hegel's master/slave dialectic to standardize the definition of

slavery, Melville reveals how the same social hegemony of white-male domination

privileged liberated individuals to take the place of master to many non-liberated

"slaves," including women, subjugated working-class men, and even America itself-the

vast expanse whose seemingly limitless land and resources was claimed and exploited in

the foundation of the United States. In fact, it is upon the subjugation of wilderness that

Melville appears to place the greatest focus. Through its use of Hegel's theoretical

framework as a key to define and identify the many forms of mastering behavior that

occur throughout The Piazza Tales-most specifically, those between man and

wilderness-Melville's text creates a clear parallel between overt forms of slavery and

seemingly benign interactions between man and wilderness.

16

Hegel's Master/Slave dialectic comes from his theoretical text Phenomenology of

Spirit-within the section titled "Independence and Dependence of Self-Consciousness:

Lordship and Bondage." As briefly summarized above, Hegel's theory details the

mutually defining relationship of two consciousnesses, and the inevitable struggle of "life

and death" that will ultimately define their dynamic as master and slave, or "Lord" and

"Bondsman" (Hegel 111 ). This process develops thusly: first there is a point of

recognition in which each consciousness becomes defined through the awareness of its

existence by the other consciousness; secondly there is an assessment of equality-the

other consciousness is recognized as not self, and is "other"; as such, the 'other' is

unessential. Next there is a "life and death struggle" to determine the essential and the

unessential being; and lastly the outcome of the struggle determines the master and the

slave, who are defined by each other-the master believes himself to live for himself

only, while the slave's life is to work for the master (Hegel 111-19 ). However, according

to Hegel, these binary roles prove to be just the opposite of what they appear, for the

"truth" of the lord is "something quite different from an independent consciousness/' and

the truth of the "servile consciousness of the bondsman" proves to be the "independent

consciousness"-meaning that the position of the master is inherently dependent upon

the slave, while the slave is not dependent upon the master ( 116, 117). The result of this

process is that since the bondsman (or the "slave," or the "subjugated individual'') is not

reliant upon the master to define him, he is afforded agency, or, as Hegel puts it,

"independence."

The most blatant example of the Hegelian Master/Slave relationship in The Piazza

Tales is between the slaves and the ship's crew in "Benito Cereno." Prior to the

17

beginning of the story, the Spanish crew of the San Dominick was overthrown by the

slaves who "revolted suddenly," "wound[ing] the boatswain and the carpender,"

"kill[ing] eighteen men," and "throwing [others] alive overboard" (Melville 105). Thus,

at the story's start, when Captain Amasa Delano comes in contact with the ship and its

crew, a very literal life-and-death struggle has already transpired, and, through the

struggle, the slaves have "made themselves masters" while the crew members have

become the "bondsmen" (Melville 105). This transfer of power was achievable because

of what Hegel claims is an inherent contradiction in all power dynamics. Although the

crew was in a dominant position, their dominance was dependent on the slaves'

subordinance. Conversely, because the slaves had no desire to maintain their subordinate

position they were not reliant upon the crew's dominance. It is in the conflict between the

master's desire to maintain his position, and the slave's desire to change his position that

Hegel claims the slave has power over the master. Since "the truth of the independent

consciousness" is "the servile consciousness of the bondsman," the slaves were, in

actuality, the "independent consciousness" and, as such, had the power to revolt. In

addition, the slaves were willing to risk their lives to achieve independence--which,

according to Hegel, is a crucial part of the struggle. He says that it is only by "showing

that [one] is not attached to any specific existence" and "staking [one's] own life" that

one can achieve a state of "being for themselves"-which is, in essence, independence

(113, 114). However, in taking the role of "Lord," the slaves lose their independence, as

they are now dependent on the crew's subordinance. The crew members, in turn, are now

independent consciousnesses as they do not rely on the slaves to maintain their position

This new independence is evident through the crew's many attempts to alert Captain

18

Delano to their situation-each of whom is essentially "staking of [his] own life" since

their attempts at revealing the revolt result in the crew member being punished (Hegel

I 13). Near the conclusion of "Benito Cereno," the crew members manage to win back

their position as master when the title character, who has been dominated by the slave

Babo throughout the story, very literally stakes his life by suddenly leaping over to

Captain Delano's ship.

The significance of Melville's use of Hegel in "Benito Cereno" is in the way in

which it aligns Hegel's master-slave dialectic with an overt depiction of slavery. Since

"Benito Cereno" is based on a true story and explores the relationships and atrocities

involved in chattel slavery, it stands out as a representation of slavery. By showing how

Hegel's theory naturally exists within the structure of chattel slavery, Melville has

created an undeniable equivalency between chattel slavery and Hegel's master-slave

dialectic within The Piazza Tales. However, the importance of this standardized

definition lies in its manifestations throughout The Piazza Tales. By utilizing Hegel's

master-slave dialectic to depict a variety of relationships, Melville seems to suggest that

chattel slavery, however horrific, was not the only form of slavery that had transpired

throughout the history of America. For example, in "Bartleby the Scrivener," the narrator,

as Bartleby's superior, should be in a position of power over Bartleby. However, over the

course of the story, he finds that he is unable to control Bartleby. Rather than do what the

narrator requests of him, Bartleby declares that he would "prefer not to"-and does just

that. The collapse of the narrator and Bartleby's power dynamic comes from Bartleby's

decision not to play the part of the employee. Since the role of the Bondsman is to fulfill

the "action of the lord," or that which the dominant consciousness requests, Bartleby is

19

disowning his position as Bondsman. Furthermore, by "prefer[ing] not to," Bartleby

enacts the power that Hegel claims the "Bondsman" possesses. 4

Although the Hegelian relationships between humans in The Piazza Tales are the

most obvious, they are not the only manifestations--nor are they the most numerous. A

clearly Hegelian dynamic occurs in "The Belltower" between clockmaker Bannadonna

and his belltower as well as the land upon which the belltower is built Bannadonna, who

has been hired to design and oversee the building of a large belltower with a clock-the

"noblest bell-tower"-is depicted, in several instances, as dominating or mastering

someone or something (174). For example, Bannadonna is described as "mounting" his

unfinished bell-tower, and "gazing upon the white summits of blue island Alps, and

whiter crests of bluer Alps off-shore-signs invisible from the plain" ( 175). Thus, in

"mounting" the tower, Bannadonna is physically dominating it, and, simultaneously,

exerting dominance over the wilderness as his man-made object affords him an elevated

position and view he would have not gotten without it (175). In addition, the tower is

built in ''renovated earth"-meaning that the ground was dug into, softened, in order to

start the tower, and thus, was physically tamed for his purpose (174). Later, as the belltower is near completion, Bannadonna believes himself to be in complete control of the

mechanics and figures, which make up the complex bell and clock system. However, it is

these objects, the very ones he believes himself to be master of, which-through

performing the functions and movements they were programmed to enact-kill him.

Finally, the very tower and earth he had also believed himself to be master of, prove him

wrong: the tower, for which the bell was too heavy, cracked, and, a year later, an

4

Actually, through his complete lack of participation in the power dynamic, Bartleby seems to forfeit his place in the Hegelian

struggle all together. He is not the "Bondsman," because his actions are no longer those of the narrator, but he is not the "Lord"

either, because he does not attempt to dominate the narrator. See chapter 3 for further discussion.

20

earthquake felled the tower entirely. Thus, as Hegel suggests, Bannadonna, as the

master, did not have absolute power over that which he dominated. Instead, the

"slaves"-through what could be characterized as "life and death struggles" since they

ended in death and destruction-appeared to have agency because they, unlike

Bannadonna, where not reliant on him to define them.

While the examples from "Benito Cereno," "Bartleby the Scrivener," and "The

Belltower," do show how parallels can be drawn between Hegel's master/slave dialectic

and Melville's works, it is also clear that drawing a comparison becomes more complex

and convoluted when attempting to use Hegel's theory to define a relationship that is not

readily recognizable as a traditional master/slave relationship-most specifically a

"mastering" relationship between man and object or man and wilderness. This is because

while there is a parallel between man's domination, or "mastering," of nature and the

Lord's mastering of the Bondsman, the utilization of Hegel's dialectic becomes

increasingly difficult when you consider that Hegel is discussing the relationship between

two consciousnesses-an attribute objects and wilderness themselves do not possess.

Without a consciousness, the object or the wilderness cannot be mastered because it is

not participating in the Hegelian struggle. However, it is apparent in ''The Belltower"

that Bannadonna believes himself to be master over things, such as the statues and the

earth, which do not possess a consciousness. Thus, the relationship between man and

wilderness is not one of real "life and death struggle" but, rather, one of a perceived

struggle, and, subsequently a perceived "mastering." In order to demonstrate how the

perception of wilderness as something that needs to be mastered, and, subsequently,

21

something that has been mastered, is formulated, it is necessary to determine how a

consciousness perceives a non-consciousness.

Both Hegel, and Bill Brown, author of"Thing Theory," discuss the process by

which an object is perceived by a consciousness, or, in Brown's case, a person. Through

this process of perception, both Hegel and Brown show how an object, or even the

wilderness, can be transformed into something with the illusion of a consciousness-a

consciousness which, therefore, can be mastered by a true consciousness. In the section

of Phenomenology ofSpirit, titled "Perception: Or the Thing and Deception," Hegel

specifically discusses the process of a consciousness perceiving an object-a process of

perception, which establishes the Thing, and its "thinghood" (68). Hegel posits that it is

through both the "perceiving" and the "being perceived" of the object-as well as the

recognition of its "Also" (that which exists in addition to its attributes), which produces

an object's "pure universal" or "'thinghood"' (67, 69, 73). Hegel suggests that it is

through the perception of a consciousness (the liberated individual) that the object (in this

case, wilderness) gains meaning-more specifically, it gains the meaning that the

perceiver bestows on it. Although "meaning" is inherently vague and intangible, it is

Hegel's use of the word "also," to describe the meaning in addition to "the thing" that

suggests that it is a quality layered onto the thing itself--a quality formulated by

perception.

Bill Brown's "Thing Theory" almost seems to pick up where Hegel's theory of

perception left off. 5 Similar to Hegel's claims regarding how a consciousness' perception

of an object establishes the Thing and its "thinghood," Brown's Thing Theory illustrates

the difference between an "object" and a "thing" as well as the process by which an

' Brown developed "Thing Theory," and is also the author of an essay titled "Thing Theory."

22

"object" becomes a '<thing." Just as depicted by Hegel, this process relies on how the

object is perceived by the human subject. However, Brown goes on to explain how

perception bestows meaning, or, in Hegel's terms, its "also." "The story of objects

asserting themselves as things," says Brown in his essay "Thing Theory," "is the story of

a changed relation to the human subject"-that changed relationship being one of

perception and recognition (4 ). Brown's theory centers around how objects gain

"thingness" when they "assert themselves" upon human subjects (4). In the context of

Thing Theory, "assert" refers to anything which forces us to "see" the object-when "you

cut your finger on a sheet of paper, you trip over some toy, you get bopped on the head

by a falling nut"; or, in a less negative context, you notice the aesthetics of, or have a

fondness for, a particular object (4). The transformation from object to thing is, thus, the

"magic by which objects become values, fetishes, idols and totems"-or, in the case of

Bannadonna, the magic by which objects gained meaning through perception and thus

became '<things" which he could master (5).

Several scenes from "The Piazza" exemplify how perception can master

wilderness. In this story, the narrator has "removed" to a remote mountaintop home. He,

like generations of early American settlers before him, finds himself in a vast, and

untamed wilderness. This wilderness is in stark contrast to the civilization with which he

is aligned-a relationship, which is evident in the fact that the narrator "removed to the

country" or, rather, "removed" from civilization to the country-the absence of

civilization ( 1). However, despite his desire to "remove" himself from civilization and

place himself in the wilderness, he, as a free white male, represents civilization and

cannot also be aligned with wilderness. Therefore, rather than simply enjoy the

23

wilderness, he oscillates between---0r rather experiences the paradoxical duality offeeling both awe at the sublimity, and terror at the wildness, of the sprawling landscape

around him-a conflict he attempts to rectify through aligning wilderness with himself

( 1). He does this by perceiving the parallels between natural objects-which are

unfamiliar and not part of civilization-and material objects-which are familiar and

identifiable as belonging to man. 6 For instance, the "limestone hills" are "galleries hung,"

his favorite seat upon a "hillside bank" is a "green velvet lounge," "road-side golden

rods" are "guide-posts" and a "hopper-like hollow" of a mountain-side is a "purpled

breast-pocket" (Melville 2, 4, 6). By creating a link between natural and material objects,

the narrator thrusts these disconcertingly wild, natural objects into the realm of the

familiar-that which is already 'owned' by man, and, more importantly, that which he

has a relationship with because they are his-and bestows them with ''thingness." This

act is vital to the narrator's ability to feel he has mastered the wilderness around him, as

the process ofthingifying results in objects having the imposed illusion of a

consciousness.

As previously suggested, another way, according to Brown, in which an object

gains ''thingness" is when the object is perceived as "[asserting] their presence and

power" (4). Brown further explains that, "we begin to confront the thingness of objects

when they stop working for us," and that objects "assert themselves as things" when "the

drill breaks, when the car stalls, when the windows get filthy" (4 ). This very act of

"asserting" is evident throughout "The Piazza." For example, on the first page, when the

narrator describes the creation of his mountaintop home-which sits amidst a vast

6

In order to differentiate between all things in wilderness and all things in civilization I am defining "natural object" as any object

found in, or that belongs to, natme (tree, rock, bird, etc.) and "material object'' as any object found in, or that belongs to, civilization

(chair, paperclip, book, etc).

24

wilderness-recounting that "in digging for the foundation the workmen used both spade

and axe, fighting the Troglodytes of those subterranean parts-sturdy roots of a sturdy

wood, encamped upon what is now a long land-slide of sleeping meadow, sloping away

off from my poppy bed" (1). Within this short passage is the full transformation of the

root from natural object, to thing, that is, to participant in a Hegelian master/slave

relationships. First, the roots are described as "not working" for the workmen--thus

forcing them to "confront the thingness" of the roots (Brown 4). The thingness of the

roots manifests in its characterization as "sturdy," which necessitates a fight in order to

remove them. Finally, the "mastering" of nature occurs in the fact that nature was fought,

defeated and, subsequently, cultivated-a conflict, which concludes in a relationship

where nature is seen as "for the other." The spot chosen was clearly unfit for building

without removal of trees~ nature was violently displaced as the workmen "fought" with

"spade and axe" until all that remained were the cast-aside corpses, the "'sturdy roots of a

sturdy wood" sitting upon the landscaped yard, which had since eroded due to removal of

the trees ( 1). Thus, through the acquisition of "thingness" because their presence

manifests through the act of "assertion," there is a built in suggestion of potential conflict

and struggle-the very makings of a Hegelian master/slave relationship. As such, these

natural objects, and wilderness as a whole, are perceived as something which can, and

must, be brought into a Hegelian struggle and, eventually, mastered.

Personification of natural objects is another perception-based means of mastering, which

is utilized by the narrator of "The Piazza" in order to align them with civilization.

Similar to the process of objectification and thingification, personification serves to pull

the natural objects out of wilderness, and position them within civilization. For example,

25

he frequently addresses the mountain ranges as if they were people: Mt. Greylock with

"all his hills about him, like Charlemagne among his peers," "certain ranges" which were

"here and there double-filed, as in platoons," and a "blue summit, peering up away

behind the rest" who will "plainly tell you" that he "considers himself. .. by several cubits

their superior" (2, 4). By choosing to perceive the individual mountains as people, the

narrator has transformed a sublimely powerful and daunting natural object into a fellow

human-something he can relate to, rather than something that threatens to dominate

him. Also, simultaneously, through continuing to view the mountains from his piazza, his

"box-royal," he is transforming the mountains into not only people, but playersperformers for his own amusement, like Jesters for a King (12).

However, as Hegel's master/slave dialectic details, the slave can never truly be

mastered. The power dynamic between the master and the slave is not an absolute binary

because the master, in actuality, needs the slave in order to exist as he does, while the

slave does not need the master-his worth comes from himself. Since the master's

identity is predicated upon his relationship as master to the slave, his identity is not

autonomous--and rather, ''the truth of the independent consciousness is accordingly the

servile consciousness of the bondsman" because the bondsman, or slave, has no

investment in staying a slave and, as such, does not rely on the master to define him

(Hegel 117). In this way, the slave is independent, whereas the master needs the slave

and, as such, is ultimately dependant. As a result, these two consciousnesses are

interlocked more intricately than if one was just dominating the other. 7 Additionally,

because the master/slave relationship between man and wilderness is actually an illusion

7

I envision this Hegelian relationship looking like the symbol of the yin·yang-filthough it still depicts the binaries of black and

white, both halves envelop a portion of the other and there is no clear top or bottom, just a sense of cyclical·ness.

26

of perception, wilderness's participation in the struggle, and wilderness's position as

"slave" are equally illusionary. Thus, wilderness has no investment in being man's slave,

in fact, wilderness just is. 8 While Man-who has built his identity, in relation to

wilderness, on being master-is dependent on wilderness. This inability for man to truly

master nature manifests itself throughout "The Piazza." Early in the story there are small

incidents of nature "rebelling" against the narrator as master: when the cold and damp of

his ''velvet lounge" allow a "sly ear-ache" to "[invade]" him; or when one of his

cultivated plants, a "Chinese creeper," becomes infested with "strange, cankerous worms

(2). In both of these cases the narrator believed himself to have civilized his immediate

wilderness. The ''velvet lounge" was the very same that he saw as his personal easychair, and the "Chinese creeper" was likely a non-native plant he chose to grow for its

aesthetic beauty. Yet, in both cases, the fact that he was not able to completely control

these elements of wilderness disrupts his sense of mastery. As the story progresses,

evidence of nature's autonomy grows: the narrator describes "blackberry brakes that tried

to pluck [him] back," a "zigzag road, half overgrown with blueberry bushes," and

"vagrant raspberry bushes-willful assertors of their right of way"-all subtle indications

of a wilderness which resists being mastered (7, 8). The most striking examples,

however, are the paradoxical occurrences of material objects, which have been all but

transformed into natural objects-mirroring the narrator's transformation of natural

objects into material objects. For example, as the narrator journeys into "fairy-land" he

encounters an "old saw-mill, bound down and hushed with vines," and, upon

encountering Marianna's cabin he is surprised to see that "the clap-boards, innocent of

8

In fact, the definition of "wilderness" dictates that it is "\Ulcultivated" and "\Ulinhabited" and thus not only doesn't need man but

ceases to be wilderness when inhabited by man.

27

paint, were yet green as the north side of lichened pines" (7, 8). In each of these

descriptions is a man-made structure or object, which attempted to impose on nature, that,

in turn, has been reclaimed by the wilderness.

In focusing on the resistance and reclamation of wilderness, Melville seems to be

alluding to two aspects of social reform. First, considering that Melville is playing with

the concept of perception throughout The Piazza Tales, the fact that the most prominent

Hegelian relationship in the text also hinges on perception is significant. Just as Melville

decenters the reader's sense of fact and fiction by bringing reality and perception into

question, he also appears to be questioning the practice of mastering wilderness, as well

as whether man has even mastered it at all. This suggestion alludes to a particular anxiety

many held in regards to the abolition of slavery, which Thomas Jefferson famously

referred to as "hav[ing] the wolf by its ears" as that they "could neither hold him, nor

safely let him go." Through his use of Hegel, Melville seems to be exploring this same

moral and social conflict While there is no question that chattel slaves were, in many

ways, very much "mastered" by slave owners, the fact that uprisings and other acts of

resistance occurred were proof that there was never complete control. Additionally, the

fact that American society had progressed to a point where the abolition of slavery was

strongly supported by a large percentage of the population further upholds the Hegelian

idea that these "Lords" did not have complete power over their "Bondsmen."

Furthermore, as Toni Morrison suggests, in the transcript of her lecture "Unspeakable

Things Unspoken," it was the very perception of natural superiority that Melville was

touching on. Morrison proposes that in writing Moby Dick Melville was particularly

concerned with questioning "whiteness idealized" and the "sin" of "racial superiority"

28

( 141, 143). The same project of deconstructing the idea of superiority appears within The

Piazza Tales in the form of the perceived mastering of wilderness. Just as with

wilderness, subjugated peoples such as chattel slaves were not choosing to participate in

the Master-Slave dialectic. As a result, a perception of mastery is, in essence, fictitious.

However, this assertion does not gloss over or negate the very real and absolutely horrific

treatment chattel slaves faced as a result of this perception. Rather, Melville is gesturing

to the fact that there was subjugation despite the illusionary nature of the Hegelian

master-slave dialectic. The way in which Melville uses Hegel throughout the text to align

the relationship between man and wilderness with the relationship between master and

slave, also suggests that he is indicating that perception, ultimately, does not matter.

Whether or not wilderness is participating in the master/slave relationship, whether or not

it is true struggle or one imagined by man, man is still actively subjugating wilderness.

Perhaps the most crucial point that Melville makes is that because wilderness is

not actively participating in the Hegelian struggle, the subjugation is coming purely from

man-from the white liberated individual. This suggests that subjugation is ultimately a

behavior or relationship dynamic that is built into the American social structure. After all,

America was built through the forceful subjugation of both wilderness and peoples and,

therefore, America was literally founded on subjugation. Similarly, Melville seems to

suggest that if subjugation is, in fact, something that is deeply ingrained in social

dynamics, it cannot simply be eliminated by amendments and social reform movements.

Thus, it is by using Hegel to show how the relationship between Man and Wilderness is

analogous to relationships in which Man is subjugated by Man, that Melville utilizes the

history of subjugated wilderness to show the likely trajectory of the social reform

29

movements which are occurring in Pre-Civil War America. Through the ways in which

Melville parallels both the Man/Wilderness relationship of early America, and the

Man/Wilderness relationships of his contemporary America that Melville suggests the

inevitable futility of social reform. It is this claim that seems to be at the center of

Melville's social criticism. From the vantage point of almost 150 years in the future it is

impossible not to recognize some poignant truth in Melville's claim. Although abolition

and suffrage both did give way to increased rights for slaves and women, and the

implementation of further civil rights acts have continued to signal the movement toward

equality for all Americans, subjugation is still a frequent, or even constant state for nonstraight, white, male Americans.

30

Chapter 2

"From the heart ofthe Hearth Stone Hills, they quarried

the Kaaba, or Holy Stone, to which, each Thanksgiving, the

social pilgrims used to come"

"The Piazza"

It is an undeniable and tragic fact that America was founded, cultivated, built, and

even defended thanks to a gruesome and horrific history of chattel slavery. While we, in

2013, might feel somewhat removed from that shameful part of our country's past, the

number of years since slavery was abolished is actually only about half the number of

years that slavery was legal and prevalent. As a result, we remain a country that is more

linked to slavery, than not. Considering how ingrained the practice of chattel slavery is in

our nation's foundation and history, it is not surprising that early Americans also acted as

"master" to other peoples and things. 9 One of these "things" was the American

Wilderness, which was often seen as 'hostile' and as something that needed to be tamed.

This attitude toward wilderness persisted up through Westward expansion and the settling

of California-at which point it seemed that the American wilderness had been tamed.

However, much like the narrator in "The Piazza"-who finds himself in a vast wilderness

within which he, a creature of civilization, has no place--the early settlers of America,

and many subsequent generations thereafter, found themselves in a vast continent of

wilderness which was unfamiliar, unknown, dangerous, and, for many, fatal. 10 In order to

9

For the purpose of this paper I am defming early Americans as people who lived before and during the Western Expansion since the

shift from aggressively "mastering" wilderness, and revering wilderness coincides with the point in time when most of lhe Nation had

been officially claimed for the United States.

10

Jamestown, the first settlement of Pilgrims experienced monumentally high mortality rates. According to Karen Ordahl

Kupperman, author of "Apathy and Death in early Jamestown," only "thirty-eight of the original 108 settlers were alive" at the end of

31

make the new world habitable, it was imperative that they believed it had been brought

out of the realm of the unknown and the wild. and into that of the known and the tamed.

The implementation of this need took the form of many different actions: some actions-such as developing towns and cities, cultivating land for agriculture, and chopping down

trees for lumber and farmland~utilized and displaced the wilderness; conversely, some

actions--such as surveying and mapping, categorizing and naming of new species of

flora and fauna, and the attributing of value to different natural resources--aimed to

transform the wilderness into something known. These same types of interactions

between man and wilderness weave throughout Melville's The Piazza Tales-especially

in "The Piazza." "The Encantadas," and "The Belltower." Throughout these stories,

Melville's depiction of man's relationship with wilderness not only mirrors Hegel's

master-slave dialectic, but also mirrors the relationship between man and wilderness that

was prevalent in the eighteenth century-as is documented in non-fiction survey texts,

such a Thomas Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia. In addition, just as Melville's

use of Hegel throughout The Piazza Tales serves to parallel the treatment of wilderness

with that of chattel slaves, the very survey texts Melville alludes to in his stories contain

similar parallels. By illuminating the overt, even violent ways in which wilderness was

subjugated and aligning them with the similar subjugation of chattel slaves--which is

depicted in both Melville's texts and the survey writing texts--The Piazza Tales creates

an undeniable parallel between the subjugation of wilderness, and the subjugation of

peoples in early America.

the first year in America. Mi1ny of these deaths were due to exposure to new diseases, exposure to severe weather, and malnutritionall of which are the result of attempting to settle in an unknown wilderness.

32

Within Melville's "The Encantadas," Salvator R. Tammoor explores and

documents the many isles that make up the Encantadas, detailing the varying flora and

fauna, as well as the "emphatic uninhabitableness" of the isles themselves-stating that

"the Encantadas refuse to harbor even the outcasts of the beasts" and that "Man and wolf

alike disown them" (127). He goes on to mention the unpredictable wind and truculent

tide, which lead to "fragments of charred wood and smoldering ribs of wrecks" as well as

"old cutlasses and daggers reduced to the mere threads of rust," and how, "mixed with

shells, fragments ofbrokenjars were lying here and there" (146). These items are all

remnants of man, who is no longer present on this island-suggesting that the island

does, in fact, refuse to harbor. The image of desolation Melville paints in this excerpt

hints at how the early Americans likely perceived the wilderness. While the American

Wilderness that the early Americans encountered did not exactly resemble the barren

Encantadas described by Tarnmoor, it was similarly deadly and unwelcoming-at least to

white men who were accustomed to the civilization of England. To them, wilderness

probably felt like it was "[refusing] to harbor" them and, thus, was an aggressor they

needed to defend themselves against. Worse, it was an unknown aggressor--0ne they

were unprepared to defend themselves against. In order to combat the fear that came from

an unfamiliar wilderness, the collection of data and information became necessary.

For early Americans, the "identification" and documentation of wilderness was

more than just a means of understanding the world around them, it was a way of feeling

in control of that terrifying unknown wilderness. In "The Encantadas," Tarnmoor

describes the flora as "tangled tickets of wiry bushes, without fruit and without a name,"

(127). Although the description of a "tangled" and "wiry" bush "without fruit" already

33

renders it uninviting, it is the fact that it is "without a name" which highlights the true

strangeness of the flora A bush "without a name" is so unknown that man has not yet

named it. This is important because, according to Christopher Looby, it is the

"knowledge of the names and qualities of the beings in nature," that was (and is), "the

basis of the American's control over his environment" (252). Because Tarnmoor's

"tangled thickets" were "without a name" they were also not something that was

controlled by man. Thus, in order to be in control of the wilderness (or in this case, the

bush), it needed to be identified, named, and documented. To achieve this control,

Americans began documenting the wilderness in a system that came to be known as the

Natural History Method which, according to Pamela Regis, author of Describing Early

America, "provided [early explorers of America] with a way oflooking at the world, with

a way of describing what they saw, and with an overarching scheme in which to fit what

they had seen" (5). Much of this documentation of the wilderness in early America took

the form of what was known as survey writing. These survey texts provided a written

"portrait" of the surrounding landscape, providing knowledge about the wilderness to

those who read it and, subsequently, demonstrating and aiding the mastery of it One such

survey writer was Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson's well-recognized text, Notes on the State of Virginia, is comprised of

twenty-three "Queries," which explore and document everything from flora and fauna to

the local government of the state of Virginia. There are five sections that address the

natural aspects of Virginia; these are titled "Boundaries of Virginia," "Rivers,"

"Mountains," Cascades" and "Productions mineral, vegetable and animal" (3). For most

sections, there are either detailed descriptions for each of the geographical

34

features/natural objects/animals discussed, or a chart detailing what Jefferson felt to be

the pertinent information for that category. Bearing an undeniable resemblance to the

style of survey-writing and documentation of the plants and animals of Virginia that

Jefferson did in Notes, Tarnmoor, narrator of"The Encantadas," provides a chart for

those who "desire the population of [the island] Albemarle"-promising that he will

"give you, in round numbers, the statistics, according to the most reliable estimates made

upon the spot" (140). The data within the chart itself notes the population of"Men,"

"Ant-Eaters," "Man-haters," "Lizards," "Snakes," "Spiders," "Salamanders," and

"Devils"-a seemingly comical and arbitrary choice of subjects to document. However,

the similarity between Tarnmoor's chart and the charts in Jefferson's text suggest that

Melville was intentionally evoking Jefferson's survey writing in order to critique it. The

satirical contrast of "statistics" and "reliable" with "estimates" that are "made upon the

spot" directly address the potential inaccuracy of the data collected, while the humorous

subject list seeks to illuminate the potential ambiguity in the naming, categorizing and

gauging of populations for various species.

The process of controlling wilderness through survey writing may seem like a

non-invasive and benign practice, however it is through the identification, naming, and

documenting or, as it could also be called, the recognition of the natural object that it

becomes an act of mastering the wilderness. Recognition is one of the first steps in

G.F.W. Hegel's master-slave dialectic. According to Hegel, it is through the "process of

Recognition" that the consciousnesses become "extremes" with "one being only

recognized, the other only recognizing" (111, 113). By this, Hegel means that through

recognition, the two consciousnesses-or in this case, man and wilderness-first split

35

into their roles of "Lord" and "Bondsman" or "Master" and "Slave" and, as a result, the

recognition allows man to achieve dominance--or at least a perceived dominance--over

wilderness. In this way, the process of identifying, naming, and documenting wilderness

was very much a process of mastering wilderness.

Melville's intention to parallel the documentation of wilderness with slavery is

evident in his evoking of Jefferson's text. In addition to Jefferson's inventory of the

wilderness of Virginia, he also has two sections where he similarly discusses Native

tribes and slaves. Through a chart, identical to the one detailing the flora and fauna,

Jefferson reduces "the American Indians" to "mere natural historical objects" (Regis

105). Similarly, in a section on the revision of British laws for the Commonwealth of

Virginia Jefferson "uses the method of natural history to demonstrate that blacks are a

different race, one that is inferior" (Regis 97). In this section, Jefferson discusses the

physical and emotional features of "the blacks," such as the source of the "black of the

negro," the fact that they "have less hair on their face and body," that they "secrete" a

''very strong and disagreeable odor," that they "seem to require less sleep," and that while

"in memory they are equal to the whites," "in reason" they are "much inferior" (145-6).

Horrible inaccuracies aside, the categorization and documentation of peoples in

Jefferson's text serves to highlight an overt parallel in how white men treated wilderness

and people of color: as things to master.

Although the naming and categorizing of wilderness did serve to master it, there

was also a strong sense of reverence for nature that traversed much of the survey writing.

For example, Jefferson's factual and subliminal description of the "Natural bridge,"

which addresses not only the physical description and the aesthetic properties, but also

36

alludes to it having an inherent value as it is "the most sublime of nature's works"-and,

thus, something unique and awe-inspiring which exists solely in America, and, even more

specifically, in Virginia (26). Therefore, these territories are valuable because of its

presence. In fact, much of Jefferson's Notes serves to document the value of America's

vast resources. In the queries titled "Rivers" and "Productions mineral, vegetable and

animal," Jefferson extensively lists resources of great potential monetary value; his use of

the word "Productions" further highlights this agenda as it denotes these natural objects

as things which are, and will be produced and used for production for the benefit of man.

"The Mississippi," Jefferson says, "will be one of the principal channels of future

commerce for the country westward of the Alleghaney"-the transport of goods to and

from America being the main focus in his surveying of Virginia's rivers (9). By

appointing value, the value of potential business which will be possible as a result of

these waterways, Jefferson is implying that the rivers are there for the use of the

American people, and that they have they right to use it; it is a part of their dominion.

Similarly, in "Productions mineral, vegetable and animal," Jefferson lists the precious