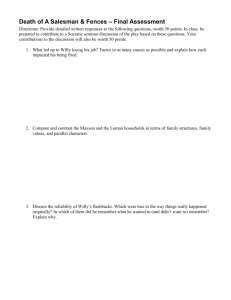

Death of a Salesman

advertisement