View a critical analysis from English 2604

advertisement

r

The

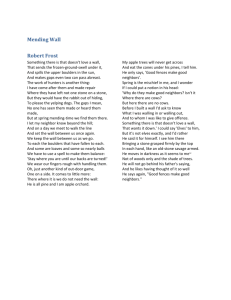

MendingWall: A Case of Misleading Simplicity

Mark Dewyea

English 2604

Dr. Welch

2/28/r0

2

Unearthing the true meaning of Robert Frost's Mending Wall requires adherence to the enduring

adage: 'T.{ever judge a book by its cover." This mindset prevents the apparent simplicity of the poem from

misleading the reader. Considering the speaker's lack of perception and ironic self-contradiction, the

possible underestimation of his neighbor's reasoning, and the ambiguous attitude Frost himself conveys

suggest the audience should conscientiously avoid accepting the poem at face value. Despite the alluring

temptation to accept the persona's apparent hatred of walls, Mending Wall intricately presents two

contradicting opinions regarding man's necessity for barriers. The paradoxical nature of the poem lies in

the fact that both views prove true. The neighbor realizes man simply cannot coexist peacefully without

the limitations of boundaries regulating interaction. The speaker voices mankind's inherent detestation

the restraints imposed by walls and the satisfaction derived from their destruction.

of

EXXffrn"

?

argument deliberately unsettled to acknowledge the coexistence of these views. This indiffArdnt

juxtaposition creates the ironic disparity between the poem's apparently straightforward meaning and the

subtler understanding that neither view prevails in reality (Barry, 110).

In Mending Wall, arock barricade divides the narrator's apple orchard from his neighbor's pineladen propeny. The majority of the blank verse poem represents the speaker's intemal monologue

contemplating the opposing view between himself and his neighbor regarding the need for walls. Every

spring the speaker seeks out his neighbor to repair the wall separating their properties. The speaker

apparently considers the wall unnecessary, as neither individual owns cows that could intrude on the

other's land. He additionally observes: "Something there is that doesn't love a wall". The neighbor refutes

his argument, simply saying, "Good fences make good neighbors". At the conclusion of the poem, the

speaker judges his neighbor as a primitive "savage", unwilling to question his inherited principles

of

times past in light of the persona's supposedly superior, enlightened views. When the narrator voices his

doubts concerning walls, the neighbor merely repeats: "Good fences make good neighbors". The poem's

I

N#,n r, o*

Tr**

structure consists of four distinct sections. In the initial section (lines 1-11), the speaker reflects on the

l

two culprits of the annual destruction of the wall: nature and humanity. An explanation of the ritual

I

I

repairing of the barrier conducted each spring follows (lines 12-30). In this section the narrator questions

the necessity of the wall only to be met with the neighbor's opposing axiom. The next section (lines

I

3l-

41) reveals the speaker's intemal reasoning why he considers walls useless. The concluding section of the

poem follows (lines 42-5I), in which he passes judgment on his neighbor's seemingly outdated attitude.

Frost uses syntax effectively to maintain tonal tension in the opening lines in order to foreshadow

the tension between the neighbor and the speaker and the incongruous appearance of the depleted wall.

His initial trochaic substitution in place of aniamb, "Something" in line one and "under" in line 2,

.onnurffih" unrhymed

vvrrucrlr/i'w

pentametSd rrr@Jvrrry

t.,.;L

sru'J'rwu iambic

r@r'urw Pw'r.'rwlw*w

majority vr

adheres to

. tr. This

of the

urv lruv'r

rv (Faggen,

\r o65wrr, 31).

foem ou'vrwD

hfr{f^

variation in rhythm reflects the similar incongruity of the wall before repaired by the neighborsrFrost's

continual variation of the traditional iambic pentameter emphasizes key words (such as "Something"),

straining against the natural rhythm. The language deviates from an iambic pattern, as evidenced by the

?T.*r.h

,;-Air^Jtr*,

"l

3

breaks in the feet found in the second and third lines that divide the words among more than one foot

(Faggen, 32.) This aspect creates an underlying tonal tension, emphasizing the poem's contradictory

views. These scarce deviations contrast sharply to the remainder of the poem. The general adherence to

iambic pentameter gives the poem a methodically deliberate tone that reinforces the "rock by rock"

process of mending the wall. Charles Bernstein recognizes Frost's ability to use the tone of his language u^ tr" ol-sr-

to correspond to his poem's content: "Mending

voice that breaks the vemacular over its lines,

l(all

is a fascinating fabrication, a metricalized, colloquial

as theme synthesizes sound"

(Bernstein, I34-I35).

The opening section (lines 1-11) of the poem begins with the understatement: "Something there is

o'something" not in favor of walls. He

that doesn't love a wall." The speaker identifies nature as the first

observes how the 'ofrozen-ground-swell" of the earth under the wall "spills the upper boulders in the sun".

The "frozen-gtound-swell" could be interpreted as frost, coincidently the author's last name. As the frost

in the poem destroys walls, this phrase implies that the poet likewise favored their removal. The remark in

line four describing the gaps made by nature's deterioration of the wall suggests that its removal increases

unity and fellowship between individuals by making: "gaps even two can pass abreast".

The speaker's early opposition to walls creates the dramatic ironv of thedrt3mr:);videnced by

Marie Borroff s reaction to the poem, the reader naturally gravitates towards the'narrator's view: "The

speaker is in sympathy with the force working form within the ground which 'doesn't love a

wall'; this

attitude is also the poet's, and the reader is invited to share in it" (Borrotr, 39). The poem's 'simplistic'

appearance is deceptive. The two central characters seem to present themselves as clear foils, each

lr",^/

h-dL"*^,

of universal

with

I

negating views. According to the persona's inconlusive vie*ythe wall's symbolization

separation evidently violates the laws ofnature. The speak6r appears to be rational, and therefore

attractive to readers, in his arguments (Coulthard, 42). This rationality, however, falters over the course

of

the poem. As literary critic John Barry points out: "The total effect of the poem is, ironically, more

thoughtful and subtle, more true to human experience" (Barry, 111).

The speaker proceeds to identiff humanity as the second "something" opposing walls. He

explains that hunters have destroyed the wall in their pursuit of rabbits, leaving "not one stone on a

stone". Lines 5-l

I include the first instances of the speaker's

self-contradiction andpuzzlement. He says

he has followed after the hunters and o'made repair" of the wall. This contradicts his

initial apparent

opposition to it, represented by his opening statement. Why maintain the wall if he truly believes it to be

an unnatural impediment to unity or fellowship between people?

Lines 10-11 question the validity of his argument that bolh man and nature oppose walls: "No one

has seen them [the gaps] made or heard them

made.'

fniJffi#the

t\'

speaker's claim that nature and

humanity oppose walls presents a mere personal assumptior; not factual evidence. The speaker never

precisely identifies the "Something" that does not love walls-

Hi; uncertainty contrasts notably with the

thisffilf

imply that true understanding of walls

apparently direct assertion: "something there

is..."

eludes the speaker's rational attempts to provide an expllnation (Barry, 110). The deliberate lack

of

4

clarity in the word "something" reflects an invitation by Frost for the reader to personally consider

it is that does not love

a

oowhat

wall". As Judith Oster explains: "A poem can be an invitation, we may get

invited in and challenged to play the game, but we are not assured of a perfect score", which holds

especially true in Mending Wall (Osteql9).

The speaker's reference to

tunt".i@iilffi},

his lack of certainty regarding the need for

o'another"

walls. His diction implies this interpretation: "The work of hunters is another thing". The words

and

"thing" appear distinctly ambiguous. The speaker presumably means that the hunter's actions are an

additional force that intrinsically recognizes the negativity of walls and wants to eradicate them (Watson,

654). His word choice implies he has little understanding of the argument he attempts to make. He fails to

recognize too the differences that nature compared to humanity visits on the wall. While nature only

upsets the "upper boulders in the sun", humanity

"left not one stone on a stone". Nature leaves the wall

somewhat intact, yet man completely destroys it. This provides a counterargument to the narrator's

assumption that nature rejects the concept of walls. AVparentlynature favors the preservation of walls to a

certain extent, but not to the point that they completely inhibit unity. Mankind, on the other hand,

seemingly hates all walls and favors their complete destruction.

The persona ironically fails to perceive that his description of the hunters resembles his

relationship with his neighbor and reinforces the latter's axiom: "Good fences make good neighbors". The

hunters' destruction of the wall in an attempt to draw out rabbits parallels, interestingly, the speaker's

opposition to its existence. The']elping dogs" may compare to the speaker's incurable urge to force his

friendship on his neighbor, who apparently shares no interest in interacting with him. Indeed, the speaker

felt he had to "let...[his] neighbor know behind the hilP' when it was time to mend the wall (Watson,

655). This situation supports the neighbor's implication that the ability of walls to prevent interaction

may not always be negative: they can protect privacy and individualism from unwanted intruders.

Reinforcing this point, William Ward says that:

Mending Wall expresses the concern that in a world which doesn't seem to love a wall

the individual may somehow get lost. Despite the obvious war appeal of the good

neighborliness that wants walls down, walls are nonetheless the essential barriers that

must exist between man and man if the individual is to preserve his own soul, and mutual

understanding and respect are to survive and flourish. (Ward, 428)

The speaker remains apparently unaware that his neighbor may not wish to interact with him beyond the

task of repairing the wall. He wishes to impose his view about walls on his neighbor ("put a notion in his

head"-line 32), much as the world attempts to impose views different from our own. The neighbor

realizes that without limitations (i.e. walls), outside forces would destroy the sense of individualism that

gives us identity. The nature of hunting reinforces the destruction of the individual. When the hunters

seek out the rabbit from hiding they do so with the intention to

neighbor in an attempt to

"kill"

kill. Likewise, the speaker draws out his

the neighbor's individuality by forcing his opinion on him.

j,,a

5

The speaker fails to recognize his own innate fondness for sheltering himself from the outside

world. He originally regards the act of the hunters to "have the rabbit out of hiding" with a negative tone,

since the resulting destruction of the wall means additional work for him. The argument here lies not

against the morality of walls, but against the constant efforts required to maintain them. He unknowingly

supports this conclusion in line 22 where he describes the tremendous exertion of mending the wall: "We

wear our fingers rough with handling them". Ironically, he unconsciously performs the same act as the

hunters against his neighbor. He draws his neighbor out of hiding only to laboriously mend the wall.

The second section of the poem (lines 12-30) describing the mending process continues to reflect

the ironic contradiction of the speaker's seemingly negative view of walls. In line

neighbor know beyond the

hill", clearly establishing that

the speaker take the initiative to maintain the wall

if

l3

he says:

"I

let my

he initiates the mending of the wall. Why would

he did not believe in it? The mending brings the

neighbors partly together, as described in line 14: "we meet to walk the line". But the wall still separates

them while they perform the chore: "We keep the wall between us as we go". They never truly come

together, which leads to the question whether this practice really exhibits a "mending-time", as suggested

in line 12. The purpose of their meeting serves only to

o'set

the wall between us once again".It seems to

instead represent a deterioration of the neighborly relationship

if viewed from the speaker's standpoint

opposing walls. Emphasizing the sense of separation is the repetition of "the wall between us" in lines 15

and 16. From the neighbor's view, ironically, the mending of the wall proves essential in maintaining

their relationship. Since "Good fences make good neighbors" the maintenance of the wall truly

"mending-time" of their relationship

.

/

ffir3

{f,)

Line 17 emphasizes the separation of the two individuals while performing the repairs: "To each

the boulders that have fallen to each". The speaker explains that they only pick up and replace the stones

found on their respective sides of the wall, therefore the process does not reflect

a

truly collaborative

effort. Each individual bears his own burden without the help of the other. The stones vary in size,

as

indicated in the metaphor in line 18: "Some are loaves and some so nearly balls". The wall prevents

cooperation, which would surely expedite the laborious task that leads the neighbors to: "Wear our fingers

rough with handling them."

saying

{

that he and the neighbor have to use a "spell" to keep them in place long enough until "their backs are

* H

The speaker suggests that the very stones comprising the wall resist their role as a barrier,

turned". This implies that the rocks themselves naturally oppose their role in walls, and only an unnatural

"spell" can hold them in place. Once again the speaker seems to argue that nature inherently

1

' ''l'\* n ..

opposes u 4"{

walls. The remalk, "Stay where you are until our backs are turnedj' identifies the wall as much of a

the *fi

rocks will fall after they depart, this doesn't matter as long as they do not witness the wall's deterioration

-:::#-" -. \"?

psychological separation as it is a physical one. Although the

'"'/#

,p#",

ffi'.#ftHl ;;"',.##;''il;- ff#

e

and the neighbor know that

;#;;"

* ;*#

:

,'*

*fi

t"t4

^, *.^

'J\4".{l/}"

o

rry' \ I hd**'b/'

hljrA

r

r[1rrr.nr.#,

'

f"; r(-

.r"r.*" t-

The description of the r4ending process as.4n "outdoor game" (line 23) with "one [neighbor] on a

side" again emphasizes th8-if

$pkfr'fud|e!,1#ffithe

mending process represents a form

?

of

competition between the two. Since ealh bears his own burden in mending the wall, "To each [go] the

boulders that have fallen to each." This description emphasizes the 'competing' opinions eachpeighbor

holds. The speaker's assumption that the process 'ocomes to little more"

(line 24) presents#tak)

understatement. The neighbors' contrasting views on walls carry profound meaning about the overall

ffi3 t**&-- -

-\'

power and morality of separation prevalent in human society.

u!,u.f,.a*r

The second section concludes with the speaker's seemingly rational argument against the need for

a

")

wall: "My apple trees will never get across and eat the cones under his pines". This statement

emphasizes not only the physical separation of the neighboring properties, but also the separation between

perspectives. Although the speaker's apparent rationality here may suggest that he is especially wise, the

neighbor remains unconvinced, replying simply: "Good fences make good neighbors".

The third section of the poem (lines 31-41) consists of the speaker's introspective consideration

of walls. In line 31 he says: "Spring is the mischief in me". This phrase connotes two main ideas: the first

a revelation in the speaker's own character, and the second a connection to Robert Frost's goal as a poet.

The speaker continually regards walls as unnatural, aligning his wish to eradicate them with nature's

7-ru

apparentlysimilarattemptsattheirdestruction.Whenthespeakersay,ttrat1ffi L,UN

me," he attempts to reinforce that alignment, as A.R. Coulthard suggests: "Like all true sons of nature, the lt^.*.-]q

speaker loves spring and under its inspiration wishes to instruct his winter minded neighbor"

(Coulthard,

t"*'T

^

e{"^q

4l). This apparent harmony with nature contributes to the reader's temptation to side with the

misleadingly perceptive speaker. While his intentions to enlighten his neighbor may initially appear

@*w"

noble, his inner dialogue reveals smugness and conceit. He only thinl<s about attempting to persuade

his

T*

neighbor to re-consider his opinion. He never verbally poses the rational argument that neither of them

own cows that need to be contained by a wall. Instead he thinks to himself: 'ol'd rather he said it for

himself. The persona has no reason to keep his neighbor uninformed other than to maintain what he

perceives as intellectually superior. He prefers to revel in his apparent wisdom, spouting condescending

maxims that do nothing but prove his own lack of insincerity towards his neighbor: "Before I built a wall

I'd

ask to know / What I was walling in or walling out" (Coulthard,

4l).

Because he did not

consider , q, d,

li(/-\

his

these questions before he voluntarily initiated the wall's repair, this statement ironically contradicts

earlier actions. He caps his obnoxious display of sophistication with the pun in line 38 in "offense" and

fence". This casual humor regarding such a serious matter casts doubt

t'lo

O

I

"{

whether the speaker truly

harbors a passionate moral objection to walls.

/" [4^

The "mischief' alluded to in line 31 reflects also Frost's aim for the poem and his own

-ambiguous consideration of walls. When asked by Leonidas Payne whether in

Y]grdllUjryAl Frost

had

fulfilled his intention "with the characters portrayed and the atmosphere of the place", he replied: "I

should be sorry

if

a single one

of my poems stopped with either of those things, stopped anywhere in fact.

7

My poems are all

set to

trip the reader head foremost into the boundless...my innate mischievousness"

(Faggen, 42).Payne explains his perception of Frost's work:

"A

meanings, not just on a first or second reading, but permanently,

a place where

reader who does not

will not

'trip' over the

be propelled into the boundless,

it is not reassuring to be but which is our true and real destination in Frost's work" (Faggen,

43). Mending Wall propels the reader into the o'boundless" by presenting the paradoxical coexistence

of

two contradicting views regarding walls. The ironic appearance that the poem opposes walls presents one

side of the reality. It remains in "deadlock" with the neighbors' contrasting views, as Frost observed:

"Poetry is neither the force nor the check. It is the tremor of the deadlock" (Faggen, 69). He was not

attempting to prove one view superior to the other. Instead, he was aware of how the two opinions both

proved true in reality. He reinforced this view in a 1915 interview: "One disposition in life is cell walls

breaking and cell walls making. Health is a period called peace in the balance between the two" (Faggen,

67). Frost does not make this distinction evident in the poem, preferring the readers to form their own

perception of the poem's meaning. Frost openly acknowledges his poem's ambiguity:

"I played exactly

fair in it. Twice I say 'Good fences make good neighbors' and twice 'Something there is that doesn't love

a

wall"' (Coulthard, 42)

In the concluding section of Mending Wall (lines 42-51\the speaker judges his neighbor. In line

44 he describes the neighbor as "an old-stone savage armed". This simile contradicts the speaker's earlier

appearance of harmony with nature. His blatantly prejudiced remark emphasizes the same intolerant

disposition of modem society. The speaker essentially constructs a mental wall separating himself from

his neighbor based on his assumed intellectual superiority. He presumes that the neighbor adheres to the

principles of an outdated era, refusing to conform to the speaker's seemingly enlightened view. The

speaker's resentment toward what he cannot understand shows his lack of tolerance, and undermines his

credibility. Such self-contradiction appears in the persona's words when in lines 49-51 he repeats his

neighbor's old adage and thereby implies that he has given the matter no thought, but only-rep-,eats

father's maxim (watson, 655). what

th@tt"plt"#;in

*t*nu"r

his ly-,2-,1t .+^n

actually

contemplated the matter and arrived at the speaker's conclusion on his own (Watson, 655). This verbal

irony filther underminer

th"tffiii"uting

his conceited perspective.

In lines 46-47 the speaker again exhibits intolerance toward his neighbor: "He moves in darkness

as

it seems to me / Not of woods only and the shade of trees". The persona acknowledges that his

neighbor's apparently benighted opinion does not lie in literal darkness, but instead remains clouded in

his mind. His failure to find any rationality behind this stance leads him to assume that his neighbor

unquestionably accepted the words of his father: "He

will not go behind his father's saying / And

he likes

having though of it so well". This judgment proves, however, to underestimate the neighbor's intellect.

The reference to him as "an old-stone savage" could be an allusion by Frost, acknowledging cultural

wisdom from the Paleolithic times as Peter Clarke explains,

r

Every year the proprietors between whose lands the holy objects lay used to meet at or

near them and offer sacrifice again. When such precautions were duly observed,

neighbors might hope that no quarrels would arise between them, and presumably that the

mere stones which were put there to mark out the boundary line would be kept in order

by their fellows (Clarke, 49)

This passage suggests that the neighbor actually possesses legitimate insight regarding the nature of walls.

There may be no need to "go behind" or to question a practice that has worked for thousands of years.

The phrase "father's saying" can be interpreted beyond the biological sense to allude to God, or

divine transcendence. This interpretation emphasizes alternatively the neighbor's religious faith

opposed to blind adherence to an old saying. Biblical support

as

forthe maintenance of walls exists in

Deuteronomy 19:14: "A curse on him who removeth his neighbor's landmark' (Clarke, 49). This passage

may help explain the neighbor's stubbom adherence to his father's adage as a divine commandment.

These allusions to ancient and biblical practices support the neighbor's opinion and sheds light on the

speaker's lack of wisdom. As Robert Faggen says: "Those regarded as low, untutored or rustic may bear

seductively a subversive from of insight, if not wisdom" (Clarke, 70).

Mending Wall implies that neither neighbors' viewpoint can

be

justified as superior. In the poem

Frost successfully emphasizes that no viable conclusion for an age-old problem can be reached, as Louis

Untermeyer explains: "The contradiction is the heart of the poem. It answers itself in the paradox

of

people, in neighbors and competitors, in the contradictory nature of man" (Untermeyer,94).

(-r*-u;-q"-t,

uot\ '*f'1d,

6'""t- e^!*ftt arw"Q*n^

Y*,* ,r,c.lt*'*0-;*J,. Q?,IA d- wt^-^f"-r^ffi-\

,i

t$d,,4

{,9

TJ* {c*<<,a-d^

%-t^t*

fl*i-6

9

Works Cited

Barry, Elaine. Robert Frost (Literature & Life). New York: Ungar Pub Co, 1973.

Borroff, Marie. "Robert Frosfs New Testament: Language and the Poem." Modern Philosophy 69 (197t):

37-44.

Clarke, Peter B. "Frost's 'Mending Wall'." Explicator 43.1 (1984): 48-50.

Coulthard, A. R. "Frost's 'Mending Wall'.' Explicator 45.2 (1987):40-42.

Faggen, Robert. The Cambridge Introduction to Robert Frost (Cambridge Introductions to Literature).

New York Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Oster, Judith. Toward Robert Frost: The Reader and the Poet. Athens, Ga: University

of

Georgia Press,

1994.

Untermeyer, Louis . Robert Frost's Poems. New York: St. Martin's,2002.

Ward, William S. *Lifted Pot Lids and Unmended Walls." College English 27.5 (1966):428-29.

Watson, Charles N., Jr. "Frost's Wall: The View from the Other Side." New England Quarterly: 44.4

(1971):653-56.