1 Proxy Politics, Economic Protest, or Traditionalist Backlash

advertisement

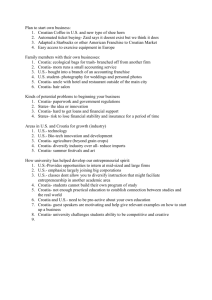

Proxy Politics, Economic Protest, or Traditionalist Backlash: Croatia’s Referendum on the Constitutional Definition of Marriage1 Josip Glaurdić Leverhulme Early Career Fellow Department of Politics and International Studies University of Cambridge Cambridge, CB3 9DT United Kingdom jg527@cam.ac.uk +44-750-327-7011 (corresponding author) Vuk Vuković Lecturer Department of Economics Zagreb School of Economics and Management Jordanovac 110 Zagreb, 10000 Croatia vuk.vukovic1@gmail.com 1 The authors express their gratitude to Ms. Irena Kravos of the Croatian Electoral Commission, Ms. Ivanka Purić of the Croatian Bureau of Statistics, Ms. Mirna Valinger of the Croatian Tax Administration, and in particular to Dr. Maruška Vizek of the Institute of Economics, Zagreb for invaluable help with data collection. 1 This article sheds light on the popular sources of opposition to the extension of gay rights in Eastern Europe by analysing the results of the 2013 Croatian referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage – the first referendum of this kind in Europe. Contrary to popular interpretations, our aggregate-level analysis reveals that the referendum results primarily reflected the pattern of support for the two principal electoral blocs, rather than communities’ traditionalist characteristics or grievances stemming from economic adversity. The article thereby stresses the importance of embedding the issue of contention over gay rights in Eastern Europe into the context of conventional political competition. There is arguably no issue demonstrating the sociocultural rift between Europe’s East and West better than the issue of same-sex marriage and gay rights in general (Štulhofer & Rimac 2009). Violence against gay activists and gay pride participants in a string of East and Southeast European countries is perhaps only the most visible aspect of that rift. No less significant, however, are the clear differences between East and West European states in the legal treatment of gay rights, as well as the pervasive political opposition to change in this sphere of human rights in Eastern Europe (Holzhacker 2013), which appears to be grounded in the persistent negative popular attitudes toward homosexuality (Brajdić Vuković & Štulhofer 2012; Inglehart & Welzel 2005). In spite of some valuable efforts at exposing the process of politicisation of (homo)sexuality in individual East European states (e.g. Keinz 2011; Mole 2011; O’Dwyer 2012; Turcescu & Stan 2005), our understanding of the popular sources of opposition to the extension of gay rights in the region is still limited. We attempt to change that by analysing the results of Croatia’s 2013 referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage – a milestone in the political battle over gay rights in Eastern Europe. Over the past decade and a half, referendums and ballot initiatives have been used by conservative activists in more than thirty US states as a method of prohibiting same-sex marriage (Lax & Phillips 2009). The Croatian referendum was the first of this kind in the European context.2 2 Three referendums close in their subject matter to Croatia’s took place in June 2005 in Switzerland, June 2011 in Liechtenstein, and March 2012 in Slovenia. The Switzerland and Liechtenstein referendums were concerning registered partnership laws. They were both approved: by 58% of the voters in Switzerland and 68.7% of the voters in Liechtenstein. The Slovenian referendum was regarding the new Family Law which was to give registered same-sex partnerships all rights of married heterosexual couples except adoption. The law was rejected, with 54.5% voting against on a 30.3% turnout. Ireland was the second European country to hold a referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage on 22 May 2015. The referendum question defined marriage as a union between two persons regardless of sex. The measure passed with 62% of the votes. 2 On 1 December 2013, in a landslide referendum vote, Croatian voters supported the insertion of a definition of marriage as a ‘life union between a woman and a man’ into the constitution. Their decision, coming after a bitter campaign which pitted a politically savvy new conservative movement backed by the Catholic Church on the one side, and the government, the largest media outlets, and the loose coalition of leftleaning NGOs on the other – offered more questions than answers. Was this merely a traditionalist backlash of a deeply conservative Southeast European country against change coming from the European Union or the West in general? Was it a form of an economic protest vote actually aimed at the disappointing performance of the ruling centre-left government coalition led by the Social Democratic Party (SDP)? Or was underneath all of this – in spite of the fact that nearly all Croatian regions voted ‘yes’ and in spite of the pro-referendum activists’ seeming detachment from mainstream politics – the pattern of competition between the two principal electoral blocs: the centre-left SDP and the centre-right Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ)? In other words, was the referendum a form of conventional politics by proxy? Answering these questions is important not only because it will shed a new light on the politics of gay rights in Croatia and the rest of post-communist Eastern Europe, but also because it will give us a better understanding of the process of interaction between conventional politics and popular demands for direct democracy in the region. Our analysis is based on an original dataset which is comprised of referendum results, series of economic and socio-demographic variables, as well as results of Croatia’s 2011 parliamentary elections – all collected on the aggregate level of more than 500 Croatian municipalities. In that sense, it is comparable to the studies of referendums in the American states which were based on county-level data (e.g. Camp 2008; McVeigh & Diaz 2009). Each one of our three lines of inquiry – proxy politics, economic protest, and traditionalist backlash – is represented by a set of independent variables, which are also supplemented with a number of important controls. Data is analysed using the beta maximum likelihood estimation method, which is supplemented with an examination of the comparative effect size of all independent variables. The remainder of the article is organised as follows. We first provide an overview of the Croatian referendum campaign, as well as the general political context in which it took place. Then we present our principal hypotheses, which are derived from the literature on popular attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights, as well as the growing literature on same-sex marriage referendums in the United States. We structure our review of these literatures according to their findings on the individual, social context, and political level. We then present our data and methods, as well as results and interpretations of our findings. Our final section 3 concludes, while drawing parallels between the Croatian referendum and similar initiatives in various US states, as well as providing implications for the future of politics of gay rights in Eastern Europe and the EU in general. The referendum campaign and the Croatian political context When it comes to gay rights and popular attitudes toward homosexuality, Croatia was no regional outlier in early 2013. It had its share of violent outbursts against gay pride marches (Bronic 2012). Its legislation on samesex partnerships (Zakon o istospolnim zajednicama) was curt and limited to certain financial and inheritance rights (Hrvatski sabor 2003b) and its Family Law (Obiteljski zakon) actually already defined marriage as a ‘life union between a woman and a man’ (Hrvatski sabor 2003a). Croatia’s centre-left government, which came to office in December 2011, paid lip-service to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights, but did little to change this legislative situation. The public opinion on homosexuality also fit the general East European pattern, though it was somewhat less homonegative than in the rest of Southeast Europe (Brajdić Vuković & Štulhofer 2012). In other words, there seemed to be no particularly ‘special’ reason why a conservative movement pushing for a referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage surfaced in Croatia in early 2013. Not least because Croatia’s referendum legislation was actually rather restrictive, with a requirement of supporting signatures by 10% of all registered voters (about 450,000 signatures) which were to be collected within a 15-day period (Hrvatski sabor 2001). Indeed, until 2013, Croatia held only two national referendums – the independence referendum in 1991 and the referendum on accession to the EU in 2012 – both of which were requested by the president and the parliament. The referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage was thus the first referendum in Croatian history which was organised due to popular demand. For careful observers of the politics of gay rights in Eastern Europe, however, the emergence of the campaign for the constitutional definition of marriage in Croatia was less surprising because it took place almost concurrently with the country’s 1 July 2013 accession into the EU. This followed a similar pattern found in the rest of the region. Although recognition of same-sex marriage was never part of conditions for EU accession, EU institutions have pushed East European accession candidates to start treating LGBT rights as human rights (Kollman 2009). However, rather than an improvement in rights and liberties of the LGBT population, the immediate effect of EU accession in a number of new member states was a significant political and social backlash (O’Dwyer 2012), leading some to consider the impact of EU conditionality in this policy area as ‘Potemkin harmonisation’ (O’Dwyer & Schwartz 2010). The emergence of a conservative social movement at 4 this particular historical juncture in Croatia’s political life was, thus, arguably a product of its interaction with the process of Europeanisation mandated by the European Union. The referendum was successfully lobbied for by a citizens’ initiative called ‘In the Name of the Family’ (U ime obitelji) which had the support of the leaders of all religious communities (IKA 2013) and a decisively strong backing of the Croatian Catholic Church.3 The initiative was officially founded in March 2013, though it had its roots in the conservative civil activist groups and right-wing political parties which had earlier led a highly visible campaign directed against the health education curriculum proposed by the Croatian Ministry of Education. One of the principal bones of contention was the curriculum’s supposed ‘promotion of homosexuality’ and ‘homosexual propaganda’ (AZOO 2013; GROZD 2013). Joined together under the umbrella of ‘In the Name of the Family’, these conservative activists cited the French movement ‘Mayors for Children’ (Maires pour l’enfance) as a direct inspiration for their new initiative. Unlike France, where there was an ex post negative popular reaction to a new law granting marriage rights to same-sex couples, with many mayors refusing to marry same-sex couples in their constituencies – leaders of the Croatian movement claimed they wanted to react ex ante, i.e. before any similar change in the status of same-sex partnerships was implemented by the Croatian government. They wanted the legal definition of marriage as outlined in the Croatian Family Law to be transferred into the constitution, thus conceivably preventing any future moves toward the equalization of marital rights between homosexual and heterosexual couples. ‘In the Name of the Family’ presented itself to the public in April 2013 and started an intensive campaign with crucial organisational and logistical support from Catholic clergy. It also cultivated transnational ties with conservative activists in the United States. The initiative claimed to finance itself mainly via donations and to rely on the work of over 6000 volunteers. Their full sources of financing, however, remained unknown, as they repeatedly refused to publicly disclose their donors’ identities (HRT 2013a). The legally required collection of referendum signatures took place between 12 and 26 May 2013 on more than 2000 locations across Croatia, many of which were local churches. During that period there were multiple reports of verbal, and at times also physical, abuse against the pro-referendum activists by individuals in mostly urban areas (e.g. Korljan 2013). In spite of such outbursts of public disapproval, and in spite of stark opposition to the referendum arising from civil society associations representing the LGBT community, as well as the generally negative attitude toward ‘In the Name of the Family’ by the mainstream media and the government, the initiative managed to 3 In the immediate run-up to the referendum, the Jewish community withdrew its support for the campaign of ‘In the Name of the Family’ (Kovačević Barišić 2013). 5 collect 749,316 signatures which were turned over to the Croatian Parliament on 14 June 2013. This completed the first step in their push for the referendum. What remained was for the government to check the validity of the signatures, and for the Croatian Parliament to either challenge the constitutionality of the proposed referendum question in front of the Constitutional Court or to set a date for the actual vote. The summer that followed was dominated by various procedural challenges to the referendum initiative by the members of the governing Kukuriku Coalition led by the Social Democratic Party (SDP).4 None of these challenges, however, came to fruition. The signature count confirmed that their number indeed satisfied the legal requirement.5 And the governing coalition was forced to opt against a constitutional challenge – most likely because it would have been nearly impossible to argue the unconstitutionality of the referendum question which merely restated the already existing legal definition of marriage from the Family Law (that was drafted, no less, by the SDP-led coalition in 2003). On 9 November the Parliament thus called for the referendum to be held on 1 December. And on 14 November the Constitutional Court issued its opinion that a possible victory for the ‘yes’ camp carried immediate legal effect, while also suggesting that the issue of constitutionality of the referendum question was misplaced because of a lack of parliamentary challenge (Ustavni sud 2013). The intervention of the Constitutional Court was the final confirmation that the pro-referendum activists managed to outmanoeuvre their opponents in the government and the NGO sector. The campaign, however, only intensified in the run-up to the vote. President Ivo Josipović, Prime Minister Zoran Milanović, and most cabinet ministers from the SDP and its coalition partners openly supported the ‘no’ campaign, as did the majority of the mainstream media (Tportal.hr 2013; Klančir 2013). Almost all major newspapers and news portals published editorials opposing the referendum and inviting readers to vote ‘no’ (e.g. Mijić 2013; Pavičić 2013). On the other hand, the principal opposition party – the centre-right Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) – officially expressed support for the referendum initiative and called on its members to vote ‘yes’ (HDZ 2013). Although this led prominent members of the ruling coalition to suggest that the referendum was an HDZ ploy aimed at destabilising the government (Dnevnik.hr 2013), the referendum initiative actually presented a significant challenge for the HDZ. The party was in the midst of internal ideological and power struggles following the 2011 electoral defeat, as well as facing criminal proceedings for 4 The coalition was named after the Kukuriku Hotel near Rijeka where the constituent parties (Social Democratic Party (SDP), Croatian People’s Party (HNS), Istrian Democratic Assembly (IDS), and the Croatian Pensioners’ Party (HSU)) signed their coalition agreement. 5 The final confirmed number of valid signatures was 683,948 (Hrvatski sabor 2013). 6 illegal party financing dating back to the era of the disgraced former Prime Minister Ivo Sanader who had been sentenced to ten years in prison for corruption. ‘In the Name of the Family’ was thus threatening to hijack the right side of the political spectrum and to step into the HDZ’s space. HDZ rank and file, as well as party local leaderships, actively supported the referendum and campaigned for its success, but the national bosses took a somewhat detached role in an effort to ‘clip the wings’ of the movement’s most prominent leaders. The ruling social democrats, on the other hand, took a diametrically opposite approach. Their national leadership vocally criticised the referendum, but they failed to offer any meaningful grassroots support for the ‘no’ camp. An additional catalyst of political conflict in the run-up to the referendum was the simultaneous campaign of various war veterans’ organisations, united in the association ‘Centre for the Defence of the Croatian Vukovar’ (Stožer za obranu hrvatskog Vukovara) for the limitation of the use of Cyrillic script only to communities where Serbs constituted a majority. Croatia’s Constitutional Law on the Rights of National Minorities guarantees equal use of minority script and language in areas where minority population exceeds one third of the total population, rather than a half, as demanded by the Stožer (Hrvatski sabor 2002). The government’s attempt to implement this law in the town of Vukovar – site of the greatest battle of Croatia’s war for independence, where the 2011 census showed the Serbs now constituted 34.9% (i.e. over one third) of the population, however, resulted in a series of protests during the fall of 2013, with the activists mounting a drive for another national referendum.6 Government officials and the mainstream media thus strongly campaigned for the ‘no’ vote on the marriage referendum not only because they viewed it as a discriminatory manipulation of the constitution, but also because they were afraid of a dangerous precedent being set which could plunge Croatia into a spiral of constitutional instability (Patković 2013). The government’s efforts, however, were to no avail. On 1 December, the ‘yes’ camp recorded a clear victory with 65.9% of the votes, though on a somewhat disappointing turnout of only 37.9%. Nineteen out of 21 Croatian counties voted ‘yes’, with only the westernmost Istria and Primorje bucking the trend. The press – in Croatia and throughout Europe – saw the result either as a sign of a conservative revolution backed by the Catholic Church or as backlash against the government which failed to spark Croatia’s economy out of its deep recession (Economist 2013; Radosavljevic 2013). The referendum certainly did not seem to have any immediate political consequences. Although the HDZ supported the referendum, particularly at the grassroots level, a public opinion survey done immediately after the referendum showed no change in popular support for the 6 The proposed referendum question was proclaimed unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court in August 2014. 7 opposition or the coalition government (HRT 2013b). In spite of speculation about the HDZ’s co-optation of the highest leadership of ‘In the Name of the Family’ (Puljić-Šego 2014), this did not materialise. A number of high-profile referendum activists actually led the formation of a new right-wing electoral bloc called Alliance for Croatia (Savez za Hrvatsku), which wanted to challenge the HDZ as the dominant party of the right, but soon fizzled out. Moreover, in July 2014 the governing coalition passed a new Law on Same-Sex Life Partnerships, which de facto equalized same-sex partnerships with marriage in all matters except adoption (Hrvatski sabor 2014). The referendum, therefore, failed to halt the expansion of rights of same-sex couples in Croatia, which are today arguably at the highest level in Eastern Europe.7 The issue seems to have disappeared from the public scene without any real understanding of the foundations of Croatian voters’ choice. Attitudes toward homosexuality and support for gay rights: deriving hypotheses Research on popular attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights has a long history. It has been reinvigorated and pushed into new directions with the issue of same-sex marriage becoming a major subject of political contention in the United States over the past decade and a half. Researchers have attempted to embed the wave of same-sex marriage ballot initiatives and referendums which have taken place in more than thirty American states into the general stream of research on US electoral politics, with special attention given to the effect of conflicts over same-sex marriage on voter mobilization, transformation of traditional party cleavages, and the supposedly deepening cultural gulf between liberals and conservatives. When it comes to research on the attitudes toward homosexuality and the politics of gay rights outside the context of US referendums, we can identify two general strands – one concentrating on values and demographic characteristics of individual voters and their families, and the other focusing on the impact of the larger social context, such as community openness, tolerance, equality, as well as economic performance. Individual-level research has shown virtually every demographic characteristic – such as race, class, gender, family status, age, education, income, and religion – as significant in determining attitudes toward gay rights. A number of studies have demonstrated that, when it comes to homosexuality in general, men tend to be less tolerant than women (Brajdić Vuković & Štulhofer 2012; Britton 1990; Yang 1997), older people tend to be less tolerant than younger people (Inglehart 1990; Loftus 2001), blacks tend to be less tolerant than whites 7 Of the post-communist East European states, only Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, and Slovenia – in addition to Croatia – have provisions for same-sex partnerships, but their legislation is more limited than the Croatian Law on Same-Sex Life Partnerships. 8 (Abrajano 2010), those who are married with children tend to be less tolerant than those who are not (Dejowski 1992), and those who could be considered working class tend to be less tolerant than the so-called professionals (Andersen & Fetner 2008). Whereas findings on the effect of income have been more varied (Gaines & Garand 2010), education has been consistently shown as a crucial predictor of liberal attitudes toward homosexuality – leading some to attribute the recent rise in support for gay rights largely to the increase in the proportion of people pursuing university education (Herek & Glunt 1993; Loftus 2001; Treas 2002). Ultimately, however, variables reflecting traditional values and religious identities have been demonstrated to have a decisive impact on attitudes toward homosexuality in general, as well as same-sex marriage and gay rights. Prejudiced attitudes toward homosexuality have thus been shown to be correlated with support of traditional sex roles (CottenHuston & Waite 1999; Polimeni, Hardie & Buzwell 2000), whereas support for gay rights has been shown to be lower among those who subscribe to traditional moral values (Brewer 2003; Campbell & Larson 2007; Wilcox et al. 2007). Similarly, when it comes to religious identity, more homonegative attitudes have been found among Orthodox Christians, Muslims, and evangelical Protestants than among Catholics (Brajdić Vuković & Štulhofer 2012; Campbell & Monson 2008) as well as among those who consider themselves religious or attend religious services more often (Brewer 2003; Haider-Markel & Joslyn 2005; Wilcox et al. 2007). Studies examining the impact of social context on attitudes toward homosexuality and on political decisions regarding gay rights have also made important contributions. Just like the proponents of contact theory convincingly demonstrated that people with gays or lesbians among their personal contacts have more tolerant attitudes toward homosexuality (Barth, Overby & Huffmon 2009; Cullen, Wright & Alessandri 2002), researchers have also found aggregate levels of tolerance to be higher in larger and more open communities, as well as in communities with higher proportions of same-sex couples (Gaines & Garand 2010; Overby & Barth 2002; Stephan & McMullin 1982; Štulhofer & Rimac 2009). On the other hand, areas where traditional gender roles and marriage patterns prevail (and particularly where communities are weak) have been shown to be less supportive of gay rights (McVeigh & Diaz 2009). More intriguingly, research has also shown the level of tolerance of homosexuality and acceptance of gay rights to be positively correlated with the level of economic development, economic equality, as well as economic performance in general (Andersen & Fetner 2008; Hodges Persell et al. 2001; McVeigh & Diaz 2009; Uslaner 2002). In other words, economic adversity and inequality likely have a negative effect on social trust and tolerance. When it comes to referendums on same-sex marriage, individual attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights (with critical influence of various aspects of the social context) obviously get channelled through the 9 more or less regular political process. In many ways, they are projected through the lens of the already existing political competition, with parties and individual political players taking various stances on the issue of samesex marriage based on their own electoral calculus. When it comes to the United States, those stances and the resulting policies more often than not reflect the general public opinion, with some bias in favour of preferences of religious conservatives due to their very well organised and powerful interest groups (Lax & Phillips 2009). Aggregate-level research in the American context has indeed shown voting patterns in state referendums to be significantly related to voting patterns in regular elections, with more Democratic counties and states tending to be more in favour of same-sex marriage (Camp 2008; McVeigh & Diaz 2009).8 This is evidently a partisan issue, even if the mainstream parties are not always – or even most times – setting the public agenda when it comes to referendums and ballot initiatives regarding same-sex marriage. The agenda is most often set exactly by those well organised religious conservative groups which have used this issue not only to effect real policy change, but also to mobilise their largely evangelical base and to implicitly shift the foundations of support within the Republican Party (Camp 2008; Campbell & Monson 2008). Considering these findings in the literature and considering the idiosyncrasies of the Croatian referendum campaign, we decided to structure our inquiry around three (sets of) hypotheses – dealing in turn with the possible effects of political allegiances; economic performance; as well as traditional values, gender roles, and marriage practices on referendum results. H1: Level of support for the constitutional definition of marriage has a positive relationship with the level of support for the HDZ and a negative relationship with the vote for the SDP-led coalition. H1a: Voter turnout in the referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage has a positive relationship with the level of support for the HDZ and a negative relationship with the vote for the SDP-led coalition. As already discussed, in the US context researchers have generally found a strong connection between party affiliation/vote share and support for same-sex marriage on the aggregate level (Camp 2008; McVeigh & Diaz 2009). In the Croatian context, levels of support for the HDZ and the SDP-led coalition are basically proxies for the principal left-right line of political division, as these two players have consistently captured between two thirds and four fifths of all votes, as well as about 90% of parliamentary seats in the last decade and a half. Our past research has also shown that the cleavages between these two parties/blocs have remained remarkably 8 But see Gaines & Garand (2010) for conflicting individual-level evidence. 10 stable during this period (Glaurdić & Vuković 2015b). Studies examining the referendums and ballot initiatives restricting same-sex marriage in US states have, furthermore, found these initiatives to have a somewhat complex mobilizing effect on voters, with evangelical Republicans coming out to the polls in droves and the secularists – Republican and Democrat – demobilising (Camp 2008; Campbell & Monson 2008). In spite of this complex US dynamic, we hypothesise that in the Croatian context the marriage referendum was a mobilising event for the HDZ voters and a demobilising event for the voters of the ruling SDP-led Coalition. H2: Level of support for the constitutional definition of marriage has a negative relationship with the level of economic performance. While economic development has been consistently shown to be a solid predictor of positive attitudes toward gay rights and same-sex marriage (Brajdić Vuković & Štulhofer 2012; Kelley 2001; Štulhofer & Rimac 2009), the impact of economic performance variables such as income, unemployment, or reliance on social welfare has been more mixed (Gaines & Garand 2010; McVeigh & Diaz 2009). Nevertheless, consistent with the literature suggesting that economic hardship can lead to a decline in social trust and tolerance (Hodges Persell et al. 2001), and in order to test a popular interpretation of the Croatian referendum as a form of economic backlash against an incompetent government, we hypothesise that lower levels of economic performance led to a higher ‘yes’ vote and a lower ‘no’ vote. H3: Level of support for the constitutional definition of marriage has a positive relationship with the level of prevalence of traditional gender roles and marriage patterns, as well as religious identification. As discussed earlier, individual level studies have consistently shown family status, attitudes toward gender roles, and various aspects of religious beliefs to have a strong relationship with attitudes toward gay rights and same-sex marriage (Brewer 2003; Campbell & Larson 2007; Haider-Markel & Joslyn 2005; Olson, Cadge, & Harrison 2006; Wilcox et al. 2007). These findings have also been confirmed on the aggregate level in the US context, with the communities characterised by traditional gender roles and family structures, as well as evangelical Christian beliefs, exhibiting strong opposition to same-sex marriage (McVeigh & Diaz 2009). We thus expect to find something similar in the analysis of the Croatian referendum results. Our expectations regarding the various control variables are discussed in the following section. 11 Data and methods Our data has been collected on the level of Croatia’s more than 500 municipalities and was provided by four institutions: Croatian Bureau of Statistics (DZS), Tax Administration (Porezna uprava), Croatia’s Electoral Commission (DIP), and the Croatian Employment Service (HZZ). The focus of our analysis is on communities, as represented by municipalities, rather than individuals – not only because of the availability of reliable data with a national reach, but also because we believe attitudes toward issues such as same-sex marriage are decisively formed through social interaction (McVeigh & Diaz 2009). There are obviously limitations to drawing individual-level inferences from aggregate-level data, but the nature of the questions we are interested in makes this methodological choice justified. The descriptive statistics of all the dependent and independent variables are presented in Table 1. [Table 1 about here] We look at referendum results not as a simple binary yes/no choice because we believe that this would not capture the voting process fully. In referenda voters actually have three choices: to vote ‘yes’, to vote ‘no’, or to abstain from voting altogether. Our three dependent variables – Marriage Yes, Marriage No, and Marriage Abstain – are, therefore, the proportions of voters who made those three choices: to vote for the constitutional definition of marriage as a life union between a woman and a man, to vote against it, or to abstain from voting.9 Figure 1 shows these three variables mapped onto Croatia’s municipalities. [Figure 1 about here] Following our theoretical considerations and the discussion of the background to the Croatian referendum, we cluster our independent variables into four groups: political, economic, traditional, and control. Our two political variables, HDZ and Kukuriku Coalition, represent the shares of votes for the two largest electoral competitors in the 2011 election: HDZ and the centre-left Kukuriku Coalition led by the Social Democratic Party (SDP). As discussed earlier, these two political variables are basically proxies for the principal left-right line of political division in Croatia akin to the Republican-Democrat division in the US. Considering 9 Looking at the referendum results in this more encompassing way raised the issue of Croatia’s problematic voter rolls, which have been in administrative disarray for years. Considering the proximity of the 2011 census to the referendum, and the fact that the census definition of adult residents was virtually identical to the legal definition of a citizen with the right to vote, we used the census figures for adult residents of a municipality as a superior measure of the number of voters than the electoral register figures. Furthermore, in our calculations we considered invalid ballots (0.6% of those who voted) as abstentions. 12 our previously posed hypotheses, this means that in practical terms we expect the higher vote shares for the HDZ to have a positive relationship with the variable Marriage Yes, as well as a negative relationship with the variables Marriage No and Marriage Abstain, whereas the opposite should hold for the Kukuriku Coalition. When it comes to economic variables, we include Unemployment (representing the average monthly unemployment rate in 2013), Income p/c (monthly per capita net income in Croatian kunas in 2013), and % Social welfare (proportion of the population receiving social welfare assistance according to the 2011 census). Following from our second hypothesis, which was posed based on the literature suggesting that economic hardship can lead to a decline in social trust and tolerance, this would mean that we expect the lower levels of income per capita, as well as higher rates of unemployment and social welfare assistance, to lead to a higher ‘yes’ vote and a lower ‘no’ vote. Capturing traditional values regarding family life on the aggregate level is challenging. Nevertheless, we feel our set of four variables – all based on the 2011 census and past aggregate-level research efforts – offer a solid foundation. The variable % Married thus measures the proportion of families in a given municipality with couples in a heterosexual marriage; % Divorced measures the proportion of the adult population which is divorced; % Workforce female represents the proportion of the municipality’s workforce which is female; and finally % Non-believers represents the proportion of the municipality’s population not belonging to any organised religion. Considering our third hypothesis, therefore, this would mean that we expect % Married to have a positive relationship with Marriage Yes and negative with Marriage No, whereas the opposite should hold for % Divorced, % Workforce female, and % Non-believers. In addition to the political, economic, and traditional clusters of potential explanatory variables, we also include six demographic controls which we find to be particularly important: Years of education, Average age, Log settlement size, % Local born, % Croats, and War disabled per ‘000. Average age represents the average years of age of the municipality’s population, whereas Years of education represents the average years of education of the municipality’s population older than 15 years of age – both based on the 2011 census. We include these variables because research has consistently shown the young and the better educated to have more tolerant attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights (Andersen & Fetner 2008; Inglehart 1990; Loftus 2001; Treas 2002). The variable Log settlement size is our measure of the municipalities’ urban/rural character and we include it because of the long line of research which has shown the size of locale to be positively related to 13 tolerance (Stephan & McMullin 1982).11 The variable % Local born, on the other hand, attempts to capture not the size, but the type of communities these municipalities are made of. It represents the proportion of inhabitants living in their municipality of birth. Our motivation for the inclusion of this variable comes from contact theory which suggests that negative views of minority groups are based on ignorance, and – since isolation leads to ignorance – contact can help change that (Allport 1954; Barth, Overby & Huffmon 2009). Although our variable is by no means a perfect test of contact theory, we believe it captures the extent to which individual municipalities are composed of insular communities. Finally, we include the variables % Croats and War disabled per ‘000 because our previous research has shown them to be the most important determinants of the pattern of voting and turnout in Croatia (Glaurdić & Vuković 2015b). The first of those two variables represents simply the proportion of Croats in the municipality’s 2011 population, with higher values consistently leading to higher turnout and disproportionately higher vote shares for the HDZ. The second variable is based on the number of disabled persons whose cause of disability was the 1991-1995 war, as tallied in the 2001 census. This variable attempts to capture the effects of the Croatian 1991-1995 war for independence on individual municipalities, and our past research has shown it to be the foundation of the strongest electoral cleavage in Croatia, with the communities which suffered more in the war disproportionately going for the HDZ. We include it in our analysis here in part due to the drive for a referendum on the use of the Cyrillic script led by the war veterans’ associations, which took place almost simultaneously to the drive for the referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage. Since our dependent variables are all proportional variables, distributed narrowly around the mean on a 0 to 1 interval, we were unable to use the ordinary least squares (OLS) method as this would violate the linearity assumptions of the conditional expectation function. Instead we apply a maximum likelihood estimation with a 11 Log settlement size in our case actually represents the log of the weighted average settlement size in a given municipality: Log settlement size = log where is the population of a settlement and ∑ ∑ is the number of settlements in a given municipality. Since each municipality consists of a number of settlements – villages, towns, cities – taking the log of a full population of a given municipality as a proxy measure for the possible effects of the urban-rural cleavage would not be methodologically sound. Our measure, we believe, more accurately captures the experience of municipalities’ inhabitants of living in locales of particular size. 14 beta redistribution (Ferrari & Cribari-Neto 2004; Paolino 2001), deemed appropriate given our sample size and dependent variables which do not include borderline values of 0 and 1 (Kieschnick & McCullough 2003). We use the Ferrari and Cribari-Neto (2004) reparameterization of a regression model for a beta distributed dependent variable and apply a maximum likelihood estimation using the statistical program STATA to estimate our parameters. We describe the advantages of applying the beta maximum likelihood estimation in greater detail in Glaurdić & Vuković 2015a. In our estimation we control for heteroscedasticity by applying a robust estimation of standard errors and test for possible problems of multicollinearity by computing variance inflation factors (VIF) for all independent variables. We find their values well below the maximum recommended value of 10 (Marquardt 1970), with the mean value of 2.74. Although multicollinearity is not an issue, parsing out the effects of our three clusters of explanatory variables can be difficult. This is particularly the case when it comes to the political cluster, which could be deemed as causally ‘shallower’ than the traditional or the economic (Kitschelt 2003). To alleviate some concerns in this regard, prior to employing the full model which includes all our explanatory variables, we test the impact of each of the three clusters on the referendum outcome independently. While this does not expose the causal mechanism behind the observed pattern of voting (for example, communities’ traditional values might be impacting their political allegiances which might in turn impact their referendum vote), it does help us understand the foundations of this pattern and the comparative explanatory power of the three sets of variables. Moreover, we should also note that our past research (2015b) has shown that in the Croatian context the pattern of communities’ party allegiances is not particularly ‘shallow’, but has actually exhibited a great dose of stability over the past decade and a half. Our full model, employing all three clusters of variables, therefore, does not merely serve as a ‘technical implementation of Ockham’s razor’ (Kitschelt 2003, p. 63). Rather, in combination with the other three models, it allows us a fairly comprehensive explanation of the pattern of voting in Croatia’s referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage. Results and interpretations The results of our analysis are presented in Table 2. The columns depict each of the three main dependent variables as the three possible choices for voters in the referendum (‘yes’, ‘no’, or abstain) within our four models. In that respect the three columns within each model should be observed simultaneously when interpreting the effects of an individual explanatory variable on the predicted voting outcome. Instead of the usual log odds obtained via maximum likelihood estimation, we report average marginal effects primarily 15 because of a more useful and easier interpretation. Average marginal effects predict the change in the dependent variable as a unit change of the independent variable (for further discussion, see Angrist & Pischke 2009, pp. 103-106). For goodness of fit, we apply the usual R2 statistic and the standard Wald test. We also report the log likelihood for each of the regressions tested. Here it would be worth mentioning that, as a form of a robustness test, we performed the same analysis using the OLS method and achieved nearly identical results. [Table 2 about here] The most striking results presented in Table 2 are obviously those related to our two political variables HDZ and Kukuriku Coalition. The findings from both Model 1 and the full model (Model 4) fit perfectly with our Hypotheses 1 and 1a. Coefficients are in the expected direction and both variables are statistically significant at the 1% level in eleven out of twelve cases. Moreover, goodness of fit measures in Model 1 are far superior to those in Models 2 and 3. In fact, they are marginally lower than those in the full model. It is clear that this referendum was a very partisan event. If we look at the figures in the full model, an extra percentage point in the 2011 vote for the HDZ brought a net gain at the referendum for the ‘yes’ camp of more than 0.6 percentage points. Similarly, an extra percentage point for the Kukuriku Coalition brought a net gain of nearly 0.5 percentage points for the ‘no’ camp. What is equally interesting, our results suggest that the referendum – although generally characterized by low turnout – disproportionally brought out the voters in areas of higher HDZ support, just as we predicted. One extra percentage point in HDZ support implied the rate of abstention was about 0.6 percentage points lower, whereas one extra percentage point in support for the Kukuriku Coalition implied the rate of abstention was about 0.1 percentage points higher. Considering these findings, one could even view Croatia’s referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage as a ‘second-order election’ in which voters’ choice is a proxy for a vote of confidence in the national government (Reif & Schmitt, 1980). On the other hand, our results show more limited evidence for the economic backlash hypothesis. Out of our three economic variables, we only see statistical significance on the 1% level for Income p/c and 10% level for Unemployment in the No column, as well as on the 10% level for Income p/c in the Abstain column of the full model. An extra percentage point in the average rate of unemployment thus implied a very modest decrease in the ‘no’ vote of 0.026 percentage points, whereas 100 Croatian kunas of additional monthly net income per capita implied an increase in the ‘no’ vote of 0.11 percentage points. These figures are stronger in the pared down Model 2, with the three economic variables reaching statistical significance at the 1% level in seven out of nine cases. Interestingly, however, whereas the coefficients for Income p/c and Unemployment are here in the expected direction, that is not the case for the variable % Social welfare, casting doubt on our 16 Hypothesis 2. Moreover, the goodness of fit measures in Model 2 are substantially lower than in the other three models. Our finding regarding the impact of income on the level of support for a constitutional definition of marriage does follow findings on county level in US states which had similar referenda (McVeigh & Diaz 2009). Nevertheless, considering the overall weakness of the findings for all three variables, we would be reluctant to suggest that our figures demonstrate the referendum results were primarily driven by sentiments of economic resentment, frustration, or perception of economic threat from the lifting of discriminatory barriers against homosexual couples. Our variables capturing traditional gender roles and family structures, as well as religious affiliation, on the other hand, seem to offer more promise. Our two variables concerned with family structure – % Married and % Divorced – reach statistical significance in three out of six cases in the full model and five out of six cases in the pared down Model 3, though with one important difference: in the pared down model % Married seems to lead to higher ‘no’ vote, whereas in the full model it leads to higher ‘yes’ vote. In spite of this twist, we can relatively safely say that, just as US counties characterised by traditional family structures demonstrated opposition to same-sex marriage in various ballot initiatives and referenda (McVeigh & Diaz 2009), so was the case with Croatian municipalities. Our proxy for traditional gender roles, % Workforce female, on the other hand, exhibits statistical significance only for the ‘no’ vote in Model 3. This is possibly owing to the fact that in the post-socialist context gender makeup of the workforce might not be the best way to capture traditional gender roles. Nevertheless, since we tested our model with several alternative variables (representing the proportion of female population that is inactive, proportion of housewives among adult women, and the level of gender segregation in educational fields) all of which were inferior to % Workforce female in improving our model and also failed to achieve any statistical significance, we are comfortable concluding that traditional gender roles did not play a part in determining the voting pattern in Croatia’s marriage referendum. However, judging by the figures for our variable % Non-believers, it seems that religion did play a significant role. As discussed earlier, leaders of all religious communities expressed support for the referendum and the ‘yes’ camp. Moreover, measuring religiosity or church attendance on the municipal level was not possible. Our variable % Non-believers is, therefore, arguably the best possible for capturing religious differences among communities. And, as the figures in both Model 3 and 4 in Table 2 show, it had a highly statistically significant effect on both turnout and the ‘no’ vote. An extra percentage point in % Non-believers led to a nearly 0.7 percentage points lower level of voting abstinence and a 0.1 percentage points higher ‘no’ vote. Interestingly, whereas referenda on same-sex marriage in the United States led to a demobilization of secularists (Campbell & Monson 2008), in 17 Croatia the opposite seems to have been the case for more secularist communities. As promising as these findings are, however, we have to note the substantially lower goodness of fit figures for Model 3, as compared to Models 1 and 4. Finally, our control variables also yielded some important results. As discussed earlier, past individuallevel research has consistently shown the young and the better educated to have more tolerant attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights (Andersen & Fetner 2008; Inglehart 1990; Loftus 2001; Treas 2002). Our aggregate-level analysis did not produce comparable results. As the full model figures in Table 2 show, Average age counterintuitively had a negative relationship with the ‘yes’ vote and a positive relationship with the ‘no’ vote. Additional years of education, on the other hand, led to nearly equally higher values for both Marriage Yes and Marriage No, primarily because they led to higher turnout. When it comes to our measure of the urban-rural cleavage Log settlement size, we get contradicting results in the first three pared down models, but ultimately find that it only had a mildly negative effect on Marriage Yes in the full model. Our variable capturing the openness of the municipalities’ communities, however, did have a statistically significant – though very modest – relationship with the ‘no’ vote in the full model. One extra percentage point in the variable % Local born resulted in a 0.025 percentage point decrease in the ‘no’ vote. In other words, residents of municipalities with more insular communities were less likely to vote ‘no’. However, arguably the most notable findings when it comes to our control variables are those related to % Croats and War disabled per ‘000. As Table 2 shows, the variable % Croats consistently led to higher ‘yes’ vote and higher turnout in all four of our models. In the full model, one extra percentage point of Croats in the municipality’s population implied the rate of abstention was 0.24 percentage points lower and the proportion of ‘yes’ votes 0.28 percentage points higher. Put differently, in areas with higher proportions of minority voters, the turnout was disproportionally lower – as was the vote ‘yes’. This dynamic can be visually observed on the lowest map in our Figure 1. The darkest patches – signifying the greatest level of abstention – roughly correspond to the territory occupied during the Croatian war for independence by the Krajina Serbs. This territory is today inhabited by both Croats and Serbs and the referendum turnout there was low in both ethnic communities. Nevertheless, it was exceptionally low in communities with a Serb majority, with figures in some villages going as low as 2%. We observed a similar dynamic in Croatia’s referendum on EU membership (Glaurdić & Vuković 2015a). Since there were no reports of any organised boycott or efforts at vote suppression in either referendum, we can only repeat the conclusion we made in the case of Croatia’s vote on EU 18 membership: low turnout in these municipalities may be seen as evidence of the deeply ingrained post-war political marginalization of the Serb community which is likely both institutional and self-imposed. As discussed earlier, our past research has shown the legacy of Croatia’s war for independence – as proxied by War disabled per ‘000 – to be the foundation of the strongest electoral cleavage in Croatia, with the communities which suffered more in the war disproportionately going for the HDZ. We included this variable in our analysis here due to the extremely polarising drive for a referendum on the use of the Cyrillic script led by the war veterans’ associations. As the figures in Table 2 show, the variable War disabled per ‘000 had a strong statistically significant effect on all three of our dependent variables in Models 2 and 3. Higher values led to higher ‘yes’ vote, lower ‘no’ vote, and lower abstention. This would suggest a reinforcing effect of the concurrent mobilization processes for the two referendums. The effect, however, washes out once we include the political variables. In Model 1, the coefficients for War disabled per ‘000 even change directions, whereas in the full model this variable seems to have a positive relationship only with Marriage Abstain. This would suggest that voters in areas that were more exposed to war violence were also more inclined to abstain from voting in the marriage referendum – once their political allegiances were taken into account. In other words, the variables HDZ and Kukuriku Coalition are likely acting as crucial intervening variables here: they are picking up the differences in the level of communities’ war exposure. Our findings suggest that popular interpretations suggesting an ideological overlap between the two referendum drives – on the constitutional definition of marriage and on the use of the Cyrillic script – need to be cautiously reconsidered and need to take political parties (particularly the HDZ) seriously into account. [Table 3 about here] As illuminating as our beta maximum likelihood estimation results are, we wanted to go one step further than the comparison of the four models and provide a sense of the comparative effect size of all our independent variables. In order to do that, we estimated Eta-squared13 and partial Eta-squared14 values for each of our independent variables. Eta-squared can be defined as the proportion of total variation in the dependent 13 Defined as: = , where is the sum of squares of the effect of interest, while is the total sum of squares for all effects, interactions and errors in the ANOVA. The formula implies we needed to use the standard OLS regression to calculate this effect. We felt confident doing that because our OLS results were nearly identical to the results of our beta maximum likelihood estimation model. 14 = , where is the error variance attributed to the effect of interest. 19 variable attributed to an effect of a specific independent variable. The larger the value of Eta-squared, the larger the effect a particular variable carries, or in other words, the higher the variance attributed to that particular variable. We also report partial Eta-squared because with Eta-squared the proportion explained by a particular variable decreases as more variables are added to the model, making it difficult to compare the effect of a variable across samples. Partial Eta-squared solves this problem by including the unexplained variation in the dependent variable (the error variance attributed to the effect) plus the variation explained by the independent variable instead of the total variation in the dependent variable – meaning that any variation explained by other independent variables is removed from the denominator. The results of our analysis are presented in Table 3, with the three variables having the highest effect values clearly marked in each column. As is obvious from our analysis, the two political variables had by far the largest effects, with the variable HDZ in particular being decisive for both Marriage Yes and Marriage Abstain. Municipalities’ vote shares for the HDZ were the primary determinants of referendum turnout and support for the ‘yes’ camp. Turnout was also particularly strongly affected by % Croats and Years of education – variables that likely had little to do with this referendum per se, but are merely the markers of greater overall electoral participation. Only in the ‘no’ vote do one traditional and one economic variable – % Non-believers and Income p/c – show up among the top-3 variables based on effect size, though even there Eta-squared and partial Etasquared values are not particularly high. This leads us to conclude that the referendum results were indeed primarily driven by the underlying political loyalties – making the referendum a form of proxy political competition between the two largest electoral camps with the victory not only in the actual result, but also in mobilization, going to the HDZ. Conclusions and implications The Croatian referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage was a milestone in the political battle over gay rights in Eastern Europe. After a string of referendums and ballot initiatives which succeeded in constitutionally limiting same-sex marriage in more than thirty US states, this was the first referendum of its kind in the European context. Conservative activists have mounted similar campaigns in a number of European countries but only in Croatia have they thus far managed to alter the constitution through a referendum. Judging by the bitterness of the referendum campaign, their direct democracy initiative intensified the nature of political competition in Croatia for a period of time, and widened it to include cultural conflicts which were earlier either absent or only fought on the margins. While it is too soon to pass a definite judgment on the long-term effects of 20 the referendum campaign on Croatia’s domestic politics, the analysis presented in this article does allow us to draw several larger lessons for our understanding of political conflict over gay rights not only in Croatia, but also in the rest of (Eastern) Europe. First, our investigation permits us to draw important parallels with comparable cases in various US states. Most obviously, a number of similarities could be identified in the patterns of referendum results, as for example in the impact of income, religious identification, or traditional family structures on the level of support for the constitutional definition of marriage. Contextual factors driving popular attitudes toward gay rights in Croatia seem to be similar to those in the United States. Moreover, the very nature of the referendum campaign in Croatia was in many ways a carbon copy of similar campaigns in the US – with a well organised conservative group driving the agenda and pressuring not only the centre-left government, but also the centre-right opposition into action. In other words, our discussion gives credence to those who see a migration of political contestation over the issue of same-sex marriage and gay rights from the United States across the Atlantic. Unlike the United States, however, where the conservative religious groups managed to translate their political capital earned in referendum battles over same-sex marriage into influence over the Republican Party, in Croatia conservative activists were pushed to the sidelines after the referendum and did not manage to penetrate into the leadership ranks of the HDZ. Considering the results of our analysis, this was hardly a surprise. Indeed, our strongest finding is that the pattern of results in the Croatian referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage reveals that the referendum was a form of politics as usual – in spite of the organisational strength of the conservative activists gathered by ‘In the Name of the Family’ and in spite of the precarious state of the HDZ. Most popular interpretations of the outcome of the referendum considered the landslide victory for the ‘yes’ camp either as a protest vote against the poor economic performance of the ruling coalition, or as traditionalist backlash against a way of life imposed from above (or the outside). We have shown that these factors were of secondary importance in determining the pattern of referendum results. This, of course, could simply be a function of the strength of Croatian parties and the party system, which have demonstrated resilience uncharacteristic of the rest of the region. Nevertheless, we would expect to observe similar dynamics throughout Europe – East and West. European parties, particularly in more institutionalized and established party systems, are likely more capable of dominating these sorts of direct democracy challenges than is the case in the United States. This does not mean that European political parties will not be put under increasing popular pressures for different social policies, particularly if the rise of far-right groups continues and if they attempt to broaden their appeal through various direct democracy initiatives. When 21 it comes to same-sex marriage, the dramatic slowdown in EU enlargement, coupled with the fact that most East European states already have constitutional definitions of marriage, may imply this issue is settled. We would argue, however, that the drastic contrast in this policy area between Eastern and Western Europe means the potential for conflict is still far from exhausted. 22 References Abrajano, M. (2010) ‘Are Blacks and Latinos Responsible for the Passage of Proposition 8? Analyzing Voter Attitudes on California’s Proposal to Ban Same-Sex Marriage in 2008’, Political Research Quarterly, 63, 4, December. Allport, G. (1954) The Nature of Prejudice (New York, Doubleday). Andersen, R. & Fetner, T. (2008) ‘Economic Inequality and Intolerance: Attitudes toward Homosexuality in 35 Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 52, 4, October. Angrist, J.D. & Pischke, J.-S. (2009) Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion (Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press). AZOO – Agencija za odgoj i obrazovanje (2013) ‘Istina o zdravstvenom odgoju’, available at: http://www.azoo.hr/images/zdravstveni/Istina.pdf, accessed 13 May 2014. Barth, J., Overby, L.M. & Huffmon, S.H. (2009) ‘Community Context, Personal Contact, and Support for an Anti-Gay Rights Referendum’, Political Research Quarterly, 62, 2, June. Brajdić Vuković, M. & Štulhofer, A. (2012) ‘“The Whole Universe Is Heterosexual!” Correlates of Homonegativity in Seven South-East European Countries’, in Ringdal K. & Simcus A. (eds) (2012). Brewer, P.R. (2003) ‘The Shifting Foundation of Public Opinion on Gay Rights’, Journal of Politics, 65, 4, November. Britton, D. (1990). ‘Homophobia and Homosociality: An Analysis of Boundary Maintenance’, Sociological Quarterly, 31, 3, Summer. Bronic, A. (2012) ‘Croatia Gay Pride March Held under Heavy Security’, Reuters, 9 June 2012, available at: http://uk.reuters.com/article/2012/06/09/uk-croatia-gay-march-idUKBRE8580B420120609, accessed 12 May 2014. Camp, B.J. (2008) ‘Mobilizing the Base and Embarrassing the Opposition: Defense of Marriage Referenda and Cross-Cutting Electoral Cleavages’, Sociological Perspectives, 51, 4, Winter. Campbell, D.E. & Larson, C. (2007) ‘Religious Coalitions for and against Gay Marriage: The Culture War Wages On’, in Rimmerman C. & Wilcox C. (eds) (2007). Campbell, D.E. & Monson, J.Q. (2008) ‘The Religion Card: Gay Marriage and the 2004 Presidential Election’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 72, 3, Fall. Cotten-Huston, A. & Waite, B. (1999) ‘Anti-Homosexual Attitudes in College Students: Predictors and Classroom Interventions’, Journal of Homosexuality, 38, 3. 23 Cullen, J.M., Wright, L.W. & Alessandri, M. (2002) ‘The Personality Variable: Openness to Experience as It Relates to Homophobia’, Journal of Homosexuality, 42, 4. Dejowski, E.F. (1992) ‘Public Endorsement of Restrictions on Three Aspects of Free Expression by Homosexuals: Socio-Demographic and Trend Analysis, 1973-1988’, Journal of Homosexuality, 23, 4. Dnevnik.h (2013) ‘Opačić: Iza referenduma i nereda u Vukovaru stoji HDZ!’ 16 November 2013, available at: http://dnevnik.hr/vijesti/hrvatska/milanka-opacic-iza-referenduma-i-nereda-u-vukovaru-stoji-hdz--311460.html, accessed 13 May 2014. Economist (2013) ‘Croatians Vote Against Gay Marriage’, 5 December 2013, available at: http://www.economist.com/blogs/easternapproaches/2013/12/croatia, accessed 13 May 2014. Ekiert, G. & Hanson, S. (eds) (2003) Capitalism and Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe (New York: Cambridge University Press). Ferrari, S. & Cribari-Neto, F. (2004) ‘Beta Regression for Modeling Rates and Proportions’, Journal of Applied Statistics, 31, 7. Gaines, N.S. & Garand, J.C. (2010) ‘Morality, Equality, or Locality: Analyzing the Determinants of Support for Same-sex Marriage’, Political Research Quarterly, 63, 3, September. Glaurdić, J. & Vuković, V. (2015a) ‘Prosperity and Peace: Economic Interests and War Legacy in Croatia’s EU Referendum Vote’, European Union Politics, forthcoming. Glaurdić, J. & Vuković, V. (2015b) ‘Voting after War: Economic Performance and Legacy of Conflict as Determinants of Electoral Support in Croatia’, Working paper, available at http:// people.ds.cam.ac.uk/jg527/voting_after_war.pdf. GROZD – Glas roditelja za djecu (2013) ‘Što je važno da roditelji znaju o uvođenju programa zdravstvenog odgoja u škole?’ available at: http://www.udruga-grozd.hr/zdravstveni-odgoj/, accessed 13 May 2014. Haider-Markel, D.P., & Joslyn, M.R. (2005) ‘Attributions and the Regulation of Marriage: Considering the Parallels between Race and Homosexuality’, PS: Political Science and Politics, 38, 2, April. HDZ (2013) ‘Izađite na referendum o braku i zaokružite ZA!’ 29 November 2013, available at: http://www.hdz.hr/vijest/nacionalne/izadite-na-referendum-o-braku-i-zaokruzite-za, accessed 13 May 2014. Herek, G.M. & Glunt, E.K. (1993) ‘Interpersonal Contact and Heterosexuals’ Attitudes toward Gay Men: Results from a National Survey’, Journal of Sex Research, 30, 3, August. 24 Hodges Persell, C., Green, A. & Gurevich, L. (2001) ‘Civil Society, Economic Distress, and Social Tolerance’, Sociological Forum, 16, 2, June. Holzhacker, R. (2013) ‘State-Sponsored Homophobia and the Denial of the Right of Assembly in Central and Eastern Europe: The “Boomerang” and the “Ricochet” between European Organizations and Civil Society to Uphold Human Rights’, Law & Policy, 35, 1-2, January-April. HRT (2013a) ‘“U ime obitelji” neće objaviti imena donatora’, 25 November 2013, available at: http://www.hrt.hr/referendum-1-12-2013/u-ime-obitelji-nece-objaviti-imena-donatora, accessed 13 May 2014. HRT (2013b) ‘Predsjedniku jedva četvorka, Vladi i Saboru dvojka’, 7 December 2013, available at: http://vijesti.hrt.hr/predsjedniku-jedva-cetvorka-vladi-i-saboru-dvojka, accessed 13 May 2014. Hrvatski sabor (2001) ‘Zakon o izmjenama i dopunama Zakona o referendumu i drugim oblicima osobnog sudjelovanja u obavljanju državne vlasti i lokalne samouprave’, Narodne novine, 92, October. Hrvatski sabor (2002) ‘Ustavni zakon o pravima nacionalnih manjina’, Narodne novine, 155, December. Hrvatski sabor (2003a) ‘Obiteljski zakon’, Narodne novine, 116, July. Hrvatski sabor (2003b) ‘Zakon o istospolnim zajednicama’, Narodne novine, 116, July. Hrvatski sabor (2013) ‘Odluka o raspisivanju državnog referenduma’, Narodne novine, 134, November. Hrvatski sabor (2014) ‘Zakon o životnom partnerstvu osoba istog spola’, Narodne novine, 92, July. IKA (2013) ‘S Devetoga međureligijskog susreta visokih predstavnika vjerskih zajednica u Hrvatskoj’, 12 November 2013, available at: http://www.ika.hr/index.php?prikaz=vijest&ID=155381, accessed 13 May 2014. Inglehart, R. (1990) Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society (Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press). Inglehart, R. & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press). Keinz, A. (2011) ‘European Desires and National Bedrooms? Negotiating “Normalcy” in Postsocialist Poland’, Central European History, 44. Kelley, J. (2001) ‘Attitudes towards Homosexuality in 29 Nations’, Australian Social Monitor, 4. Kieschnick, R. & McCullough, B.D. (2003) ‘Regression Analysis of Varieties Observed on (0, 1): Percentages, Proportions and Fractions’, Statistical Modelling, 3. Kitschelt, H. (2003) ‘Accounting for Outcomes of Post-communist Regime Diversity: What Counts as a Good Cause?’ in Ekiert, G. & Hanson, S. (eds) (2003). 25 Klančir, I. (2013) ‘Josipović: Izići ću na referendum i glasovati protiv’, Večernji list, 4 November 2013, available at: http://www.vecernji.hr/hrvatska/josipovic-izici-cu-na-referendum-i-glasovati-protiv-900981, accessed 13 May 2014. Kollman, K. (2009) ‘European Institutions, Transnational Networks and National Same-Sex Union Policy: When Soft Law Hits Harder’, Contemporary Politics, 15, 1. Korljan, Z. (2013) ‘Pankerice razbile štand crkvenih aktivista udruge “U ime obitelji” koji su protiv gay brakova!’ Jutarnji list, 17 May 2013, available at: http://www.jutarnji.hr/pankerice-razbile-standcrkvenih-aktivista-koji-su-protiv-gay-brakova/1103259/, accessed 13 May 2014. Kovačević Barišić, R. (2013) ‘Židovska općina Zagreb protiv referenduma’, Večernji list, 15 November 2013, available at: http://www.vecernji.hr/hrvatska/referendumsko-pitanje-zadire-u-prava-manjina-903030, accessed 13 May 2014. Lax, J.R. & Phillips, J.H. (2009) ‘Gay Rights in the States: Public Opinion and Policy Responsiveness’, American Political Science Review, 103, 3, August. Loftus, J. (2001) ‘America’s Liberalization in Attitudes toward Homosexuality, 1973 to 1998’, American Sociological Review, 66, 5, October. Marquardt, D.W. (1970) ‘Generalized Inverses, Ridge Regression and Biased Linear Estimation’, Technometrics, 12. McVeigh, R. & Diaz, M.-E. D. (2009) ‘Voting to Ban Same-Sex Marriage: Interests, Values, and Communities’, American Sociological Review, 74, 6, December. Mijić, B. (2013) ‘Mi smo protiv’, Novi list, 16 November 2013, available at: http://www.novilist.hr/Vijesti/Hrvatska/Mi-smo-PROTIV, accessed 13 May 2014. Mole, R. (2011) ‘Nationality and Sexuality: Homophobic Discourse and the “National Threat” in Contemporary Latvia’, Nations and Nationalism, 17, 3. O’Dwyer, C. (2012) ‘Does the EU Help or Hinder Gay-Rights Movements in Postcommunist Europe? The Case of Poland’, East European Politics, 28, 4. O’Dwyer, C. & Schwartz, K.Z.S. (2010) ‘Minority Rights After EU Enlargement: A Comparison of Antigay Politics in Poland and Latvia’, Comparative European Politics, 8, 2. Olson, L.R., Cadge, W. & Harrison, J.T. (2006) ‘Religion and Public Opinion about Same-Sex Marriage’, Social Science Quarterly, 87, 2, June. 26 Overby, L.M. & Barth, J. (2002) ‘Contact, Community Context, and Public Attitudes toward Gay Men and Lesbians’, Polity, 34, 4, Summer. Paolino, P. (2001) ‘Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Models with Beta-Distributed Dependent Variables’, Political Analysis, 9, 4. Patković, N. ‘Premijer Milanović: “Dok sam ja na čelu Vlade referendum o ćirilici neće proći”’, Jutarnji list, 2 December 2013, available at: http://www.jutarnji.hr/milanovic--vlada-nije-mogla-sprijeciti-referendumo-braku--ali-ovaj-o-cirilici--dok-sam-je-predsjednik-vlade--nece-nikada-proci--neka-to-dobro-cuju/1143921/, accessed 13 May 2014. Pavičić, J. ‘Referendum o braku protivan je kršćanskim načelima. Izađite i glasajte protiv’, Jutarnji list, 4 November 2013, available at: http://www.jutarnji.hr/referendum-o-braku--izadite-i-glasajte-protivprotukrscanska-akcija-protiv-manjina/1137618/, accessed 13 May 2014. Polimeni, A.-M., Hardie, E. & Buzwell, S. (2000) ‘Homophobia among Australian Heterosexuals: The Role of Sex, Gender Role Ideology, and Gender Role Traits’, Current Research in Social Psychology, 5, 4, March. Puljić-Šego, I. (2014) ‘Veliko okupljanje desnice: Pregovori Željke Markić i Tomislava Karamarka’, Večernji list, 28 January 2014, available at: http://www.vecernji.hr/hrvatska/karamarko-preko-zeljke-markicnastoji-doci-i-do-potpore-crkve-917548, accessed 13 May 2014. Radosavljevic, Z. (2013) ‘Croats Set Constitutional Bar to Same-Sex Marriage’, Reuters, 1 December 2013, available at: http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/12/01/uk-croatia-referendumidUKBRE9B005V20131201, accessed 13 May 2014. Reif, K. & Schmitt, H. (1980) ‘Nine Second-Order National Elections – A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results’, European Journal of Political Research, 8, 1. Rimmerman, C. & Wilcox, C. (eds) (2007) The Politics of Same-Sex Marriage (Chicago, University of Chicago Press). Ringdal, K. & Simcus, A. (eds) (2012) The Aftermath of War: Experiences and Social Attitudes in the Western Balkans (London, Ashgate). Stephan, G.E. & McMullin, D.R. (1982) ‘Tolerance of Sexual Nonconformity: City Size as a Situational and Early Learning Determinant’, American Sociological Review, 47, 3, June. Štulhofer, A. & Rimac, I. (2009) ‘Determinants of Homonegativity in Europe’, Journal of Sex Research, 46, 1. 27 Tportal.hr (2013) ‘Referendum izaziva nelagodu, glasujte protiv‘, available at: http://www.tportal.hr/vijesti/hrvatska/301853/Referendum-izaziva-nelagodu-glasujte-protiv.html, accessed 13 May 2014. Treas, J. (2002) ‘How Cohorts, Education, and Ideology Shaped a New Sexual Revolution on American Attitudes toward Nonmarital Sex, 1972-1988’, Sociological Perspectives, 45, 3, Fall. Turcescu, L. & Stan, L. (2005) ‘Religion, Politics and Sexuality in Romania’, Europe-Asia Studies, 57, 2, March. Uslaner, E.M. (2002) The Moral Foundations of Trust (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). Ustavni sud Republike Hrvatske (2013) ‘Priopćenje o narodnom ustavotvornom referendumu o definiciji braka’, Narodne novine, 138, November. Wilcox, C., Brewer, P.R., Shames, S. & Lake, C. (2007) ‘If I Bend This Far I Will Break? Public Opinion About Same-Sex Marriage’, in Rimmerman C. & Wilcox C. (eds) (2007). Yang, A.S. (1997) ‘Trends: Attitudes toward Homosexuality’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 61, 3, Autumn. 28 Table 1. Descriptive statistics Mean St.dev. Min Max Marriage Yes 0.274 0.111 0.007 0.818 Marriage No 0.083 0.051 0.006 0.262 Marriage Abstain 0.640 0.102 0.165 0.971 HDZ 0.179 0.097 0.003 0.675 Kukuriku Coalition 0.244 0.098 0.019 0.523 1739.2 463.1 415.8 3258.4 Unemployment 0.218 0. 099 0. 052 0. 566 % Social welfare 0.055 0.034 0 0.216 % Married 0.812 0.035 0.684 0.901 % Divorced 0.032 0.012 0.005 0.071 % Workforce female 0.416 0.041 0.208 0.506 % Non-believers 0.035 0.037 0 0.232 Average age 42.64 3.33 33.1 63.3 Years of education 9.84 0.87 5.93 12.13 Log population 3.01 0.54 1.65 5.78 % Local born 0.636 0.122 0.219 0.944 % Croats 0.889 0.172 0.018 1 8.54 8.08 0 64.98 Income p/c War disabled per ‘000 29 Table 2. Beta maximum likelihood estimation results Model 1 Model 2 Yes No Abstain HDZ 0.585*** (0.048) -0.092*** (0.014) Kukuriku Coalition -0.318*** (0.042) 0.207*** (0.014) Yes Model 3 No Abstain Yes No Model 4 Abstain Yes No Abstain -0.651*** (0.060) 0.547*** (0.054) -0.078*** (0.015) -0.588*** (0.064) 0.052 (0.047) -0.285*** (0.043) 0.159*** (0.015) 0.124*** (0.046) Political Economic Income p/c -2.2x10-5 (1.8x10-5) 2.7x10-5*** (4.8x10-6) -2x10-5 (1.8x10-5) -3.5x10-6 (1.2x10-5) 1.1x10-5*** -2.5x10-5 * (3.5x10-6) (1.3x10-5) Unemployment 0.295*** (0.074) -0.106*** (0.021) -0.240*** (0.076) 0.031 (0.044) -0.026* (0.015) -0.041 (0.051) % Social welfare -0.343** (0.141) 0.127*** (0.046) 0.319** (0.144) -0.016 (0.094) 0.047 (0.035) 0.03 (0.103) Traditional % Married 0.199 (0.150) 0.082** (0.040) -0.308** (0.149) 0.345*** (0.101) 0.019 (0.027) -0.407*** (0.11) % Divorced -3.623*** (0.538) 1.181*** (0.126) 2.907*** (0.535) -0.491 (0.344) 0.408*** (0.095) 0.279 (0.381) % Workforce female -0.036 (0.118) 0.095*** (0.035) -0.002 (0.118) 0.027 (0.089) -0.008 (0.028) 0.01 (0.103) % Non-believers -0.05 (0.117) 0.252*** (0.042) -0.676*** (0.117) 0.143 (0.107) 0.113*** (0.029) -0.687*** (0.117) Demographic controls Average age -0.004*** (0.001) 0.003*** (0.0003) 0.0003 (0.001) 0.001 (0.001) 0.002*** (0.0004) -0.002 (0.001) 0.004** (0.001) 0.0005 (0.0004) -0.005*** (0.002) -0.002** (0.001) 0.002*** (0.0004) 0.001 (0.001) Years of education 0.024*** (0.004) 0.025*** (0.002) -0.052*** (0.005) 0.010 (0.012) 0.023*** (0.003) -0.029** (0.011) -0.009 (0.008) 0.032*** (0.002) -0.013* (0.008) 0.021*** (0.006) 0.019*** (0.002) -0.029*** (0.007) Log settlement size -0.017*** (0.006) 0.007*** (0.002) 0.009 (0.007) -0.016* (0.008) 0.006** (0.003) 0.009 (0.007) 0.026*** (0.008) -0.012*** (0.002) -0.020*** (0.008) -0.011* (0.006) 0.002 (0.002) 0.007 (0.007) 0.051* (0.026) -0.048*** (0.008) -0.010 (0.028) 0.088** (0.038) -0.046*** (0.009) -0.035 (0.037) -0.110** (0.033) 0.035*** (0.011) 0.066** (0.033) 0.034 (0.028) -0.025*** (0.008) -0.033 (0.031) % Croats 0.287*** (0.023) 0.010 (0.006) -0.224*** (0.023) 0.466*** (0.026) -0.03*** (0.009) -0.394*** (0.025) 0.422*** (0.032) -0.014* (0.008) -0.389*** (0.029) 0.28*** (0.026) 0.008 (0.006) -0.236*** (0.024) War disabled per ‘000 -0.001* (0.0004) 0.0002* (0.0001) 0.001** (0.0005) 0.003*** (0.0004) -0.001*** (0.0002) -0.002*** (0.0005) 0.003*** (0.0004) -0.001*** (0.0002) -0.002*** (0.0004) -0.001 (0.0005) 0.0001 (0.0001) 0.001** (0.0005) % Local born 30 Observations 2 R Wald chi-square (d.f.) Prob > chi-square Log likelihood 546 546 546 546 546 546 546 546 546 546 546 546 0.772 0.897 0.672 0.761 0.882 0.640 0.449 0.812 0.389 0.532 0.814 0.473 1328 (8) 4086.2 (8) 848.9 (8) 709.4 (9) 2242.5 (9) 549.7 (9) 747.8 (10) 2096.8 (10) 657.2 (10) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 842.2 1496 758.3 630.2 1339.3 619.77 671.4 1360 659.1 855.8 1532.5 785.6 ***p<0.01. **p<0.05. *p<0.1. Standard errors in parentheses. 31 1701.8 (15) 4127.1 (15) 1089.3 (15) Table 3. Effect size estimates Marriage Yes Marriage No Marriage Abstain HDZ 9.94 ① (29.42) 0.163 (1.58) 10.68 ① (24.45) Kukuriku Coalition 2.29 ③ (9.79) 2.6 ② (20.46) 0.694 (2.07) Income p/c 0.003 (0.015) 0.974 ③ (8.78) 0.178 (0.54) Unemployment 0.019 (0.081) 0.007 (0.074) 0.04 (0.124) Social welfare 0.021 (0.088) 0.026 (0.258) 0.006 (0.021) % Married 0.663 (2.71) 0.019 (0.188) 0.927 (2.73) % Divorced 0.20 (0.832) 0.135 (1.316) 0.102 (0.309) Female workforce 0.019 (0.081) 0.066 (0.651) 0.0001 (0.001) % Non-believers 0.086 (0.362) 3.41 ① (25.19) 1.55 (4.51) Average age 0.221 (0.919) 0.632 (5.87) 0.008 (0.026) Years of education 0.624 (2.55) 0.697 (6.44) 1.70 ③ (4.9) Log population 0.112 (0.468) 0.19 (1.84) 0.027 (0.082) % Local born 0.249 (1.04) 0.136 (1.33) 0.135 (0.407) 2.84 ② (10.65) 0.041 (0.40) 3.8 ② (10.35) 0.453 (1.86) 0.053 (0.52) 0.717 (2.13) Political Economic Traditional Demographic controls % Croats War disabled per ‘000 Table reports η2 and partial η2 (in parentheses), all multiplied by 102 for ease of presentation. Symbols ①②③ denote the first, second, and third largest effects in each column. 32 Figure 1. Referendum results 33