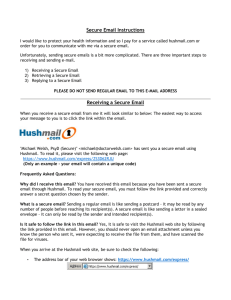

Encrypted Email HUSHMAIL - Look

advertisement

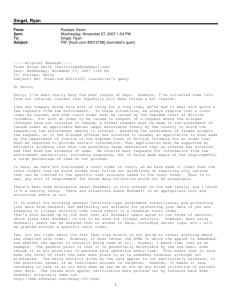

Encrypted E-Mail Company Hushmail Spills to Feds By Ryan Singel 11.07.07 3:39 PM Hushmail, alongtime provider of encrypted web-based email, markets itself by saying that "not even a Hushmail employee with access to our servers can read your encrypted e-mail, since each message is uniquely encoded before it leaves your computer." But it turns out that statement seems not to apply to individuals targeted by government agencies that are able to convince a Canadian court to serve a court order on the company. A September court document (.pdf) from a federal prosecution of alleged steroid dealers reveals the Canadian company turned over 12 CDs worth of e-mails from three Hushmail accounts, following a court order obtained through a mutual assistance treaty between the U.S. and Canada. The charging document alleges that many Chinese wholesale steroid chemical providers, underground laboratories and steroid retailers do business over Hushmail. The court revelation demonstrates a privacy risk in a relatively-new, simple webmail offering by Hushmail, which the company acknowledges is less secure than its signature product. A subsequent and refreshingly frank e-mail interview with Hushmail’s CTO seems to indicate that government agencies can also order their way into individual accounts on Hushmail’s ultra-secure web-based e-mail service, which relies on a browser-based Java encryption engine. Since its debut in 1999, Hushmail has dominated a unique market niche for highly-secure webmail with its innovative, client-side encryption engine. Hushmail uses industry-standard cryptographic and encryption protocols (OpenPGP and AES 256) to scramble the contents of messages stored on their servers. They also host the public key needed for other people using encrypted email services to send secure messages to a Hushmail account. The first time a Hushmail user logs on, his browser downloads a Java applet that takes care of the decryption and encryption of messages on his computer, after the user types in the right passphrase. So messages reach Hushmail’s server already encrypted. The Java code also decrypts the message on the recipient’s computer, so an unencrypted copy never crosses the internet or hits Hushmails servers. In this scenario, if a law enforcement agency demands all the e-mails sent to or from an account, Hushmail can only turn over the scrambled messages since it has no way of reversing the encryption. However, installing Java and loading and running the Java applet can be annoying. So in 2006, Hushmail began offering a service more akin to traditional web mail. Users connect to the service via a SSL (https://) connection and Hushmail runs the Encryption Engine on their side. Users then tell the server-side engine what the right passphrase is and all the messages in the account can then be read as they would in any other web-based email account. The rub of that option is that Hushmail has — even if only for a brief moment — a copy of your passphrase. As they disclose in the technical comparison of the two options, this means that an attacker with access to Hushmail’s servers can get at the passphrase and thus all of the messages. In the case of the alleged steroid dealer, the feds seemed to compel Hushmail to exploit this hole, store the suspects’ secret passphrase or decryption key, decrypt their messages and hand them over. Hushmail CTO Brian Smith declined to talk about any specific law enforcement requests, but described the general vulnerability to THREAT LEVEL in an e-mail interview (You can read the entire e-mail thread here): The key point, though, is that in the non-Java configuration, private key and passphrase operations are performed on the server- side. This requires that users place a higher level of trust in our servers as a trade off for the better usability they get from not having to install Java and load an applet. This might clarify things a bit when you are considering what actions we might be required to take under a court order. Again, I stress that our requirement in complying with a court order is that we not take actions that would affect users other than those specifically named in the order. Hushmail’s marketing copy largely glosses over this vulnerability, reassuring users that the non-Java option is secure. Turning on Java provides an additional layer of security, but is not necessary for secure communication using this system[...] Java allows you to keep more of the sensitive operations on your local machine, adding an extra level of protection. However, as all communication with the webserver is encrypted, and sensitive data is always encrypted when stored on disk, the non-Java option also provides a very high level of security. But can the feds force Hushmail to modify the Java applet sent to a particular user, which could then capture and sends the user’s passphrase to Hushmail, then to the government? Hushmail’s own threat matrix includes this possibility, saying that if an attacker got into Hushmail’s servers, they could compromise an account — but that "evidence of the attack" (presumably the rogue Java applet) could be found on the user’s computer. Hushmail’s Smith: [T]he difference being that in Java mode, what the attacker does is potentially detectable by the user (via view source in the browser). "View source" would not be enough to detect a bugged Java applet, but a user could to examine the applet’s runtime code and the source code for the Java applet is publicly available for review. But that doesn’t mean a user could easily verify that the applet served up by Hushmail was compiled from the public source code. Smith concurs and hints that Hushmail’s Java architecture doesn’t technically prohibit the company from being able to turn over unscrambled emails to cops with court orders. You are right about the fact that view source is not going to reveal anything about the compiled Java code. However, it does reveal the HTML in which the applet is embedded, and whether the applet is actually being used at all. Anyway, I meant that just as an example. The general point is that it is potentially detectable by the end-user, even though it is not practical to perform this operation every time. This means that in Java mode the level of trust the user must place in us is somewhat reduced, although not eliminated. The extra security given by the Java applet is not particularly relevant, in the practical sense, if an individual account is targeted. (emphasis added) [...] Hushmail won’t protect law violators being chased by patient law enforcement officials, according to Smith. [Hushmail] is useful for avoiding general Carnivore-type government surveillance, and protecting your data from hackers, but definitely not suitable for protecting your data if you are engaging in illegal activity that could result in a Canadian court order. That’s also backed up by the fact that all Hushmail users agree to our terms of service, which state that Hushmail is not to be used for illegal activity. However, when using Hushmail, users can be assured that no access to data, including server logs, etc., will be granted without a specific court order. Smith also says that it only accepts court orders issued by the British Columbia Supreme Court and that non-Canadian cops have to make a formal request to the Canadian government whose Justice Department then applies, with sworn affidavits, for a court order. We receive many requests for information from law enforcement authorities, including subpoenas, but on being made aware of the requirements, a large percentage of them do not proceed. To date, we have not challenged a court order in court, as we have made it clear that the court orders that we would accept must follow our guidelines of requiring only actions that can be limited to the specific user accounts named in the court order. That is to say, any sort of requirement for broad data collection would not be acceptable. I was first tipped to this story via the Cryptography Mailing List, and Kevin, who had been talking with Hushmail about similar matters involving another case, followed up with Smith. We both agree Hushmail deserves credit for its frank and open replies (.pdf). Such candor is hard to come by these days, especially since most ISPs won’t even tell you how long they hold onto your IP address or if they sell your web-surfing habits to the highest bidders.