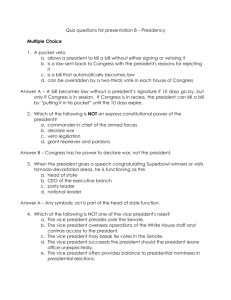

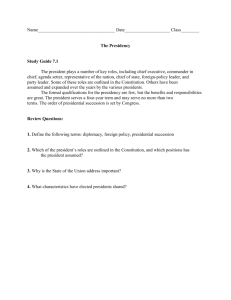

presidential succession and inability

advertisement