Indian Removal - Portland State University

advertisement

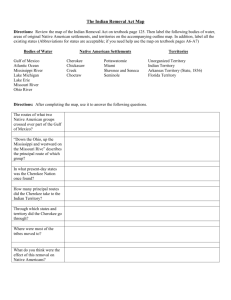

Indian Removal TAHPDX: Teaching American History Project 2009 Beth Cookler Veronica Dolby Gabor Muskat Ilana Rembelinsky Mario Sanchez http://www.upa.pdx.edu/IMS/currentprojects/TAHv3/Curricula.html Table of Contents Introduction to Indian Removal Guide Essential Question Guide Rationale Learning Goals Page 3 Historical Background Narrative Sources & Bibliography Page 4 Indian Removal Map Analysis Activity Page 9 Document-Based Question Activity DBQ Middle and Sheltered High School DBQ High School DBQ Documents Rationale Page 12 Page 22 Page 33 Drama: Shall We Leave Our Land? Page 35 Other Classroom Activities Page 42 Annotated Bibliography Page 44 2 Introduction to Indian Removal Guide Essential Question How do the Louisiana Purchase and the subsequent Indian Removal Act and displacement of the Cherokee reflect conflicting opinions and changing federal Indian policy? Rationale The purpose of this unit is to illustrate both the Native American perspective and the dominant culture’s perspective on the Louisiana Purchase and the subsequent displacement of Native Americans. During this unit students will investigate and evaluate the political, social and economic impacts of political decisions on Native Americans. Students will gain a deeper understanding of the various concepts of land ownership. Learning Goals Students will be able to: • Understand the scope and extent of Native American displacement. • Evaluate the impact of the Louisiana Purchase on the Cherokee. • Increase their ability to understand various perspectives in looking at history. • Heighten their awareness about the complicated interactions between Native Americans and the dominant culture. • Examine how politicians weigh what is just and ideal vs what is practical or achievable. 3 Indian Removal Background Narrative The background narrative is designed to provide the teacher with information that will assist in presenting this subject matter in the classroom. The annotated bibliography provides further resources. 4 Historical Background Narrative The European settlers of North America and, later, the United States Government developed changing and conflicting opinions and policies towards Native Americans. Similarly, Native Americans developed diverse reactions to those policies as well. Below is brief summary of how policy toward the Native Americans changed, beginning with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and ending with the Cherokee removal from Georgia and the Trail of Tears. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 Native Americans occupied the North American continent long before the arrival of Europeans. The population of European immigrants in North America grew rapidly and eventually developed an insatiable desire for land stretching from the Atlantic to Pacific Oceans. From the very first series of contacts with the Native Americans, the new Euro-Americans believed that they had discovered the continent and were thus entitled to its land. This belief in the private ownership of land resulted in a numerous encounters between the Native Americans and the new Americans, oftentimes adverse to Native Americans. As the young United States continued to expand its boundaries westward to the Pacific Ocean, the new Americans met with Indian nations that had historically occupied the land. The newcomers needed land for settlement, and they aggressively sought it by sale, treaty or by force of arms. In 1787, in the pursuit of western lands, the United States Congress under the Articles of Confederation approved the Northwest Ordinance. The Ordinance set up a government for the Northwest Territory (see map) and provided for the vast region to be divided into separate territories that could petition to become states when the territory reached a population of 60,000 [white] settlers. The Northwest Ordinance accelerated the westward expansion of the United States into lands occupied by Native Americans. Because of this, the Ordinance had a specific clause that addressed the problem. It stated that “the utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed.” Despite the intentions of the Northwest Ordinance to respect Native lands, white settlers and land speculators poured into the Northwest Territory, squatting on Indian lands by the thousands. This resulted in numerous conflicts between Indians and settlers and wars between Indian nations and the U.S. government. Despite the explicit language of the Northwest Ordinance to honor and protect the Native American’s claims to their lands, the United States government most often favored white settlers and promoted westward expansion. 5 The Louisiana Purchase and Indian Removal Between 1790 and 1830, tribes east of the Mississippi River, including the Cherokees, signed many treaties with the United States government. Although the treaties ostensibly were entered into in good faith, the United States government struggled to find a balance between the obligation of the new nation to uphold its treaty commitments and the desires of its new citizens for more and more land. Any good faith of the United States government was quickly abandoned when faced with the growing pressure to adopt policies favoring westward expansion. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson believed that the Louisiana Territory purchase would solve the problem of Indian and white relations. The Louisiana Purchase added almost one million sparsely populated square miles west of the Mississippi River to the United States (see map). At the time of the purchase, Jefferson believed that the Indians would willingly sell their lands east of the Mississippi and agree to relocate to the vast lands west of the river and live in peace without interference from the whites. Also, Jefferson believed that white settlements would not encroach upon the lands west of the Mississippi for at least fifty years. He was wrong on both counts. First, the Native Americans were fundamentally tied to their lands. Most of the efforts at voluntary relocations that involved land swaps were untenable to the Indians, who wanted to remain on their traditional lands. Second, Jefferson grossly underestimated the rate of western expansion and the insatiable desire for land by white settlers. Jefferson was correct, however, that the lands west of the Mississippi would provide necessary land for the relocation of the Native Americans living east of the Mississippi, but only temporarily. Contrary to Jefferson’s belief that the Louisiana Purchase would alleviate the “Indian problem,” the purchase instead accelerated pressure to remove Indians to the newly available lands. The Cherokee Example Under Article VI of the Louisiana Purchase treaty, the United States had agreed to honor existing treaties with Native Americans "until, by mutual consent of the United States and the said tribes or nations, other suitable articles shall have been agreed upon." Proponents of Indian removal to west of the Mississippi River seized upon the "other suitable articles" language in the Louisiana Purchase to make their case for removing Native American tribes from their ancestral homelands. Specifically, the treatment of the Cherokees living in Georgia exemplifies how the Louisiana Purchase impacted Indian nations living east of the Mississippi. 6 Beginning in 1791, a series of treaties between the Cherokee nation and the United States federal government gave recognition to the Cherokee as a nation with its own laws and lands. Nevertheless, a growing nation, a growing white population and issues of states’ rights complicated the continuing policy of recognizing Indian nations, and the Cherokees, in particular. In 1802, Georgia ceded all of its western lands to the federal government with the expectation that all titles to land in Georgia held by the Cherokee would be extinguished by the federal government. That did not happen. In 1828, Georgia passed a law pronouncing all laws of the Cherokee Nation to be null and void. In 1829, gold was discovered in Georgia on Cherokee land, which intensified Georgia’s efforts to gain ownership of these lands. Finally, in 1830, the United States Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. After heated debate, the Act passed by one vote in the U.S. Senate. Passage of the Indian Removal Act eventually led to the forcible removal of the Cherokee from Georgia to Indian Territory, located in present day Oklahoma. By 1835, the Cherokee were politically divided and despondent. Most Cherokees supported Principal Chief John Ross, who fought the encroachment of whites starting with the 1832 land lottery. However, a minority (fewer than 500 out of 17,000 Cherokee in North Georgia) followed Major Ridge, his son John, and Elias Boudinot, who advocated removal. The Treaty of New Echota, signed by Major Ridge and members of the Treaty Party in 1835, gave President Andrew Jackson the legal document he needed to remove the Cherokees despite protest by Chief Ross. Ratification of the treaty by the United States Senate sealed the fate of the Cherokee Nation. Among those who spoke out against the ratification were Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, but it nonetheless passed by a single vote. In 1838 the United States began the forced removal of Cherokee, fulfilling a promise the government had made to the State of Georgia in 1802. Ordered to remove the Cherokee, General John Wool resigned his command in protest, delaying the action only slightly. His replacement, General Winfield Scott, arrived at New Echota on May 17, 1838 with 7,000 heavily armed forces. The forced migration of the Cherokee to Indian Territory is known as the Trail of Tears. Background Narrative Bibliography: Many of the sources and materials used for this background narrative come from TAHPDX: Great Decisions in American History, A Teaching American History Project in partnership with the Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies at Portland State University and the Portland, Beaverton, Hillsboro and Forest Grove School Districts, funded by the US Department of Education. This site provides an excellent overview of the Louisiana Purchase and its impact on Native Americans living east of the Mississippi River. Available at http://www.upa.pdx.edu/IMS/currentprojects/TAHv3/Content/Louisiana_Purchase.html. The following websites were also essential in composing the background narrative: 1. See http://www.pbs.org/ktca/liberty/popup_northwest.html for a brief description of the Northwest Ordinance. 2. http://www.nps.gov/archive/jeff/LewisClark2/Circa1804/Heritage/LouisianaPurchase/Louisi anaPurchase.htm This site from the National Park Service provides a brief, but detailed, history of the Louisiana Purchase. 7 3. See http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2959.html for an article on the history of Indian removal, generally. 4. http://www.cherokeehistory.com/ This site provides an excellent history of the Cherokee and served as a principal source for the Historical Background Narrative. 5. http://www.cherokee.org/ This cite provides a concise history of the roundup of the Cherokee in Georgia from the native perspective. 6. Beyond Worcester: The Alabama Supreme Court and the Sovereignty of the Creek Nation, Tim Alan Garrison. Journal of the Early Republic, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Autumn, 1999), pp. 423-450; Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press on behalf of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic. This article gives a detailed account of the Supreme Court cases authored by Justice Marshall granting the Cherokee independent sovereign nation status. The article details the pressure on Georgia politicians and courts to remove the Cherokee from Georgia as the white population of Georgia grew and after gold was discovered. 7. The following site gives a concise account of the internal conflict within the Cherokee on the issue of removal which was whether to go peacefully or whether to resist relocation forcefully (http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2959.html). From the site: The Cherokee, on the other hand, were tricked with an illegitimate treaty. In 1833, a small faction agreed to sign a removal agreement: the Treaty of New Echota. The leaders of this group were not the recognized leaders of the Cherokee nation, and over 15,000 Cherokees -- led by Chief John Ross -- signed a petition in protest. The Supreme Court ignored their demands and ratified the treaty in 1836. The Cherokee were given two years to migrate voluntarily, at the end of which time they would be forcibly removed. By 1838 only 2,000 had migrated; 16,000 remained on their land. The U.S. government sent in 7,000 troops, who forced the Cherokees into stockades at bayonet point. They were not allowed time to gather their belongings, and as they left, whites looted their homes. Then began the march known as the Trail of Tears, in which 4,000 Cherokee people died of cold, hunger, and disease on their way to the western lands. 8. How the Indians Lost their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005. The United States government shaped the legal framework under which the European settlers could dispossess the Native Americans of land making it easy to acquire land claimed by Native Americans. 9. The Louisiana Purchase: Jefferson's Noble Bargain? (Monticello Monograph Series, distributed for the Thomas Jefferson Foundation) and Levinson, Sanford and Bartholomew Sparrow, ed., The Louisiana Purchase and American Expansion, 1803-1898. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005. 10. For a discussion of the Cherokee Indian cases before the United States Supreme Court in the 1830s on the issue of Indian sovereign nation status see http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/antebellum/landmark_cherokee.html. 8 Indian Removal Map Analysis Activity 9 Indian Removal Mapping Activity The Indian Removal Google Earth project organizes data folders and layers that show Native American cultural groups, the various Trails of Tears and population expansion westward. Review basic geographic concepts: • Absolute and Relative Location • Latitude/Longitude • Direction & Distance • Cardinal Directions (North, South, East, West) • Push/Pull Factors To complete this activity, secure a computer lab and confirm that it has Google Earth loaded. Have students run through a quick Google Earth tutorial to get familiar with the program and how to navigate the map layers. A short tutorial can be found on the TAHPDX <Curricula> webpage at http://www.upa.pdx.edu/IMS/currentprojects/TAHv3/Curricula.html (linked at the top of the page. The Indian Removal Google Earth project can be opened (double-click) directly from the TAHPDX <Curricula> webpage. It will be included with the Indian Removal Guide (listed alphabetically on this page). -------------------------------------------------Mapping Activity Focus Question: Predict the factors contributing to the decision to remove American Indian tribes from their native lands. Instructions: Your group has been assigned an American Indian tribe to learn about. For your tribe, you are going to follow the journey through early United States history, examining the interaction between your tribe and the American government. Tribes: Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw Launch the Indian Removal Google Earth Project; use the following layers to answer the questions below in a notebook: • • • • • • • • Pre-Settlement Indian Languages Map Trail of Tears Map 1830-1835 Current Geography: Rivers Land assigned to Emigrant Indians 1836 “In Time and Place” web link from the Cherokee Census data 1800 Population per county 1830 Population per county Ruler tool and thumbtack to measure distance 10 1. Find your tribe’s location on the Pre-Settlement Indian Languages map. From the center point of that location, what is the latitude and longitude of your tribe’s piece of land? 2. Evaluate the geographical features of that location. What natural resources might your tribe have benefited from? 3. Now look at the Trail of Tears map and the Land Assigned to Emigrant Indians map. Where did your tribe move to? What is the latitude and longitude of the new location? 4. Using the ruler tool, measure the distance of your tribe’s journey. How far did they have to travel to their new location? (If there is more than one route, choose one.) 5. Evaluate the geographical features of the route. What obstacles may your tribe have encountered on their journey? Be specific. 6. Which tribe(s) already lived in that location? Predict whether your tribe may have lived in peace with other tribes or whether conflict may have arisen. 7. Evaluate the geographical features of the new location. What natural resources might your tribe have benefited from in the new place? 8. Examine the census data from the Population per County maps from 1800 and 1830. a. What changes do you notice? b. How might changes in population affect the decision of the United States government to remove your tribe from its native land? 9. What other factors may have motivated the United States government to decide that the removal of your tribe was necessary and important for the United States? 10. From the perspective of your tribe, how might you have felt if the US government forced you to leave your native land and travel to a new location? 11 Indian Removal Document-Based Question Activity Middle and Sheltered High School 12 DBQ Hook Activity Question: What is the relationship between the arrival of the European settlers and the territorial claims of indigenous populations over time? This activity is a simulation of how territory changed ownership over time between the European settlers and the Native Americans. Start with the whole class sitting comfortably at their seats. Announce that all students are members of a Native American tribe and this is their ancestral homeland. For each round, use a random method of selecting 2-3 students (depending on size of class) who will switch roles. Suggested methods of selection: birthday closest to date, first letter of first name closest to the beginning of the alphabet, clothing specification, etc. Round 1 Announce that the two students selected randomly (see above) encountered settlers on their land and they were shot. They die and their new role is to be European Settlers. Give settlers one quarter of the room to occupy and then have the remaining students (Native Americans) move to the remaining part of the room. Round 2 Announce that the two students selected randomly (see above) got the measles from contact with European settlers and died. Their new role is to be European Settlers. Give settlers one half of the room to occupy and then have the remaining students (Native Americans) move to the remaining part of the room. Round 3 Announce that the two students selected randomly (see above) died of starvation due to loss of hunting and agricultural lands. Their new role is to be European Settlers. Give settlers three quarters of the room to occupy and then have the remaining students (Native Americans) move to the remaining part of the room. Round 4 Announce that for their own protection from the settlers the Native Americans have been given new territory that they need to move to immediately. The settlers must escort them to their new territory. (Teacher brings students to a previously arranged location on the school grounds. If possible arrange to move students to an occupied classroom, foreign language class would be best if possible where students don’t understand the language being spoken.) Debrief Return to class when ready. Start with a 5 minute quick write about the experience and have students write down 1 question. Discuss main lesson question and student questions as a class. 13 DBQ Question: Did the Trail of Tears represent change in federal policy towards Native Americans, as demonstrated through its dealings with the Cherokee people? Background Information (for student) In 1787, the United States Congress approved the Northwest Ordinance. This Ordinance accelerated the westward expansion of the United States into lands already occupied by Native Americans. Because of this, the Ordinance had a specific clause that addressed the problem. It stated that “the utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed.” Despite the intentions of the Northwest Ordinance to respect native lands, white settlers and land speculators poured westward, squatting on Indian lands by the thousands. This resulted in numerous conflicts between Indians and settlers and wars between Indian nations and the U.S. government. Despite the explicit language of the Northwest Ordinance to honor and protect the Native American’s claims to their lands, the United States government most often favored white settlers and promoted westward expansion. The United States Constitution also has a clause that addresses how the government should deal with Indian nations. Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 states “The Congress shall have power…to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes…” The Commerce Clause represents one of the most fundamental powers delegated to the Congress by the founders, a definition of the balance of power between the federal government, the states, and the Indian nations. In 1828, Georgia claimed the right to make laws for the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee went to the Federal Courts to defend their right to make their own laws and maintain their property rights as an independent nation within the United States. Their case reached the United States Supreme Court. In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Chief Justice John Marshall, writing the majority opinion for the Court, declared Georgia’s action unconstitutional. The opinion recognized the Cherokee’s status as a sovereign nation, meaning that the Cherokee had absolute authority over its territory. However, President Andrew Jackson refused to recognize the Court’s authority and failed to enforce the Court’s decision. Instead, Jackson sided with Georgia and said that the federal government would not interfere with a state’s right to pass laws relating to issues within its borders. As a result, the Federal Government would not intervene and stop Georgia from extending its authority over Cherokee lands, thus opening up the Cherokee lands to white settlers. As the population of whites grew in Georgia, more and more began to settle in western Georgia, the area of Georgia where the Cherokee lived. Though treaties between the Cherokee and the Federal Government guaranteed these lands to the Cherokee, the encroachment of white settlers sparked conflicts with the Cherokee, who were aggressively defending their territory. The growing conflict was exacerbated by the discovery of gold on Cherokee lands. 14 In 1830, at the urging of President Jackson, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. The Act authorized the Federal government to pay Native Americans to move west of the Mississippi River. The exercise of this federal power had more far reaching consequences however. In 1835, the Federal Government forced the Cherokee to agree to a disputed Treaty of New Echota, in which the Cherokee agreed to give up all of their ancestral lands in Georgia. In 1838, an army of 7,000 federal troops came to remove the Cherokee from their lands and lead them west. Under threat of force, the Cherokee agreed to leave, knowing that resistance would ultimately lead to their destruction. More than 15,000 Cherokee began their long and sorrowful march to the west, traveling hundreds of miles over a period of several months. They had little food or shelter. The Cherokee people call this journey the "Trail Where We Cried” (also known as the “Trail of Tears”) because of its devastating effects. The Cherokee faced hunger, disease, and exhaustion on the forced march. Over 4,000 Cherokees died on the journey, mostly children and the elderly. National Park Service, Trail of Tears. 15 DBQ Question: Did the Trail of Tears represent change in federal policy towards Native Americans, as demonstrated through its dealings with the Cherokee people? DBQ Documents Note: A rationale for inclusion of the documents is included at the end of the DBQ activity. The sources of the documents can be found in the Annotated Bibliography. Teachers can use their discretion as to which documents they feel would be most appropriate for the students they will be teaching. -------------------------------------------------- Document 1: Treaty at Hopewell, 1785 Excerpts from Treaty at Hopewell with the Cherokee Nation, November 28, 1785 Background: On November 28, 1785, the Treaty of Hopewell was signed between the U.S. representative Benjamin Hawkins and the Cherokee Indians at the plantation of Andrew Pickens on the Seneca River in northwestern South Carolina. The treaty laid out a western boundary where white settlement would not be allowed to expand. ARTICLE V. If any citizen of the United States, or other person not being an Indian, shall attempt to settle on any of the lands westward or southward of the said boundary which are hereby allotted to the Indians for their hunting grounds, or having already settled and will not remove from the same with six months after the ratification of this treaty, such person shall forfeit the protection of the United States, and the Indians may punish him or not as they please… ARTICLE XII. That the Indians may have full confidence in the justice of the United States, respecting their interests, they shall have the right to send a deputy of their choice, whenever they think fit, to Congress. Questions: 1. Who are the parties to the Treaty and when was it passed? 2. How does this Treaty protect Indian Lands? 3. What rights do the Cherokee have if the terms of the Treaty are violated? 16 Document 2: Cherokee Land Maps (1791-1838) Teacher Note: Print this in color so the boundary lines are clear. Red boundary line indicates Cherokee land. Cherokee Land Maps-Original Claims, 1791, and Before Indian Removal 1838 Guiding Questions: 1. Use an atlas and identify which present day states the Cherokee lands were located in for the various time periods. 2. What is happening to the Cherokee land over time? 3. Based on the boundaries of the Cherokee lands in 1838, why might Georgia be the state most active in pursuing Indian removal? 17 Document 3: Indian Removal Act of 1830 Indian Removal Act of 1830 (excerpts) An Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states of territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That it shall and may be lawful for the President of the United States to cause so much of any territory belonging to the United States, west of the river Mississippi, not included in any state of organized territory, and to which the Indian title has been extinguished, as he may judge necessary, to be divided into a suitable number of districts, for the reception of such tribes of nations of Indians as may choose to exchange the lands where they now reside, and remove there; and to cause each of said districts to be so described by natural or artificial marks, as to be easily distinguished from every other. Guiding Questions: 1. What kind of connections can you make between the Louisiana Purchase and Indian Removal to lands west of the Mississippi River? 2. What is the Act’s expectation of Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River? 3. Hypothesize what the impact of Indian Removal would be on tribes west of the Mississippi River. 18 Document 4: Great Heroes of Real Estate Guiding Questions: 1. Whose picture is on this Twenty Dollar Bill? 2. How does this image connect the person with the Indian Removal Act? 3. What do you think is the significance of the stamp: "Great Heroes of Real Estate"? Who do you think it refers to? 4. Do you think this artist would have supported the Cherokee’s rights to keep their land, or Jackson’s Indian Removal Policy? Explain why. 19 Document 5: Cherokee Trail of Tears Timeline The Cherokee Trail of Tears Timeline 1838 February March April May June July August September October November December 15,665 people of the Cherokee Nation approach Congress protesting the Treaty of New Echola. Outraged American citizens throughout the country approach Congress on behalf of the Cherokee. Congress tables statements protesting Cherokee removal. Federal troops ordered to prepare for roundup. Cherokee roundup begins May 23, 1838. Southeast suffers worst drought in recorded history. Tsali (a Cherokee) escapes roundup and returns to North Carolina. First group of Cherokees driven west under Federal guard. Further removal aborted because of drought and "sickly season." Over 13,000 Cherokees imprisoned in military stockades await break in drought. Approximately 1500 die in confinement. In Aquohee stockade, Cherokee chiefs meet in council, reaffirming the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation. John Ross becomes superintendent of the removal. Drought breaks. Cherokee prepare to embark on forced march to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. Ross wins additional funds for food and clothing. For most Cherokee, the "Trail of Tears" begins. Thirteen contingents of Cherokees cross Tennessee, Kentucky and Illinois. First groups reach the Mississippi River, where their crossing is held up by river ice flows. Contingent led by Chief Jesse Bushyhead camps near present day Trail of Tears Park. John Ross leaves Cherokee homeland with last group, carrying the records and laws of the Cherokee Nation. 5000 Cherokees trapped east of the Mississippi by harsh winter, many die. Guiding Questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. What evidence is there about the Cherokee response to the removal? What evidence is there about the response of the American public to the removal? How did the weather impact the move west? What does the timeline tell you about the conditions faced by the Cherokee along the Trail of Tears? 20 Document 6: The Trail of Tears The Trail of Tears (author unknown) We walked that trail, tears in our eyes, dragging our feet in weariness. How could we have believed all their lies? Leaving nothing but blood, they slaughtered our mothers and daughters, and after all was gone, they claimed this land was their “Father’s.” The Trail of Tears. We believed their evil smiles, and believed that they would save us, and now we know the truth, nothing can save the lost. They took our spirit, and fulfilled our every fear, killed our hope, and now we walk. Guiding Questions: 1. What does the author think about the promises of the U.S. government? 2. How does this poem contradict the speech by Jackson about the benefits of relocation for Indians? 21 Indian Removal Document-Based Question Activity High School 22 DBQ Hook Activity Question: What is the relationship between the arrival of the European settlers and the territorial claims of indigenous populations over time? This activity is a simulation of how territory changed ownership over time between the European settlers and the Native Americans. Start with the whole class sitting comfortably at their seats. Announce that all students are members of a Native American tribe and this is their ancestral homeland. For each round, use a random method of selecting 2-3 students (depending on size of class) who will switch roles. Suggested methods of selection: birthday closest to date, first letter of first name closest to the beginning of the alphabet, clothing specification, etc. Round 1 Announce that the two students selected randomly (see above) encountered settlers on their land and they were shot. They die and their new role is to be European Settlers. Give settlers one quarter of the room to occupy and then have the remaining students (Native Americans) move to the remaining part of the room. Round 2 Announce that the two students selected randomly (see above) got the measles from contact with European settlers and died. Their new role is to be European Settlers. Give settlers one half of the room to occupy and then have the remaining students (Native Americans) move to the remaining part of the room. Round 3 Announce that the two students selected randomly (see above) died of starvation due to loss of hunting and agricultural lands. Their new role is to be European Settlers. Give settlers three quarters of the room to occupy and then have the remaining students (Native Americans) move to the remaining part of the room. Round 4 Announce that for their own protection from the settlers the Native Americans have been given new territory that they need to move to immediately. The settlers must escort them to their new territory. (Teacher brings students to a previously arranged location on the school grounds. If possible arrange to move students to an occupied classroom, foreign language class would be best if possible where students don’t understand the language being spoken.) Debrief Return to class when ready. Start with a 5 minute quick write about the experience and have students write down 1 question. Discuss main lesson question and student questions as a class. 23 DBQ Question: Did the Trail of Tears represent change in federal policy towards Native Americans, as demonstrated through its dealings with the Cherokee people? Background Information (for student) In 1787, the United States Congress approved the Northwest Ordinance. This Ordinance accelerated the westward expansion of the United States into lands already occupied by Native Americans. Because of this, the Ordinance had a specific clause that addressed the problem. It stated that “the utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed.” Despite the intentions of the Northwest Ordinance to respect native lands, white settlers and land speculators poured westward, squatting on Indian lands by the thousands. This resulted in numerous conflicts between Indians and settlers and wars between Indian nations and the U.S. government. Despite the explicit language of the Northwest Ordinance to honor and protect the Native American’s claims to their lands, the United States government most often favored white settlers and promoted westward expansion. The United States Constitution also has a clause that addresses how the government should deal with Indian nations. Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 states “The Congress shall have power…to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes…” The Commerce Clause represents one of the most fundamental powers delegated to the Congress by the founders, a definition of the balance of power between the federal government, the states, and the Indian nations. In 1828, Georgia claimed the right to make laws for the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee went to the Federal Courts to defend their right to make their own laws and maintain their property rights as an independent nation within the United States. Their case reached the United States Supreme Court. In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Chief Justice John Marshall, writing the majority opinion for the Court, declared Georgia’s action unconstitutional. The opinion recognized the Cherokee’s status as a sovereign nation, meaning that the Cherokee had absolute authority over its territory. However, President Andrew Jackson refused to recognize the Court’s authority and failed to enforce the Court’s decision. Instead, Jackson sided with Georgia and said that the federal government would not interfere with a state’s right to pass laws relating to issues within its borders. As a result, the Federal Government would not intervene and stop Georgia from extending its authority over Cherokee lands, thus opening up the Cherokee lands to white settlers. As the population of whites grew in Georgia, more and more began to settle in western Georgia, the area of Georgia where the Cherokee lived. Though treaties between the Cherokee and the Federal Government guaranteed these lands to the Cherokee, the encroachment of white settlers sparked conflicts with the Cherokee, who were aggressively defending their territory. The growing conflict was exacerbated by the discovery of gold on Cherokee lands. 24 In 1830, at the urging of President Jackson, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. The Act authorized the Federal government to pay Native Americans to move west of the Mississippi River. The exercise of this federal power had more far reaching consequences however. In 1835, the Federal Government forced the Cherokee to agree to a disputed Treaty of New Echota, in which the Cherokee agreed to give up all of their ancestral lands in Georgia. In 1838, an army of 7,000 federal troops came to remove the Cherokee from their lands and lead them west. Under threat of force, the Cherokee agreed to leave, knowing that resistance would ultimately lead to their destruction. More than 15,000 Cherokee began their long and sorrowful march to the west, traveling hundreds of miles over a period of several months. They had little food or shelter. The Cherokee people call this journey the "Trail Where We Cried” (also known as the “Trail of Tears”) because of its devastating effects. The Cherokee faced hunger, disease, and exhaustion on the forced march. Over 4,000 Cherokees died on the journey, mostly children and the elderly. National Park Service, Trail of Tears. 25 DBQ Question: Did the Trail of Tears represent change in federal policy towards Native Americans, as demonstrated through its dealings with the Cherokee people? DBQ Documents Note: For each of the documents there is a rationale for their inclusion located at the end of the DBQ activity. The sources of the documents can be found in the Annotated Bibliography. Teachers can use their discretion as to which documents they feel would be most appropriate for the students they will be teaching. -------------------------------------------------- Document 1: Treaty at Hopewell, 1785 Excerpts from Treaty at Hopewell with the Cherokee Nation, November 28, 1785 Background: On November 28, 1785, the Treaty of Hopewell was signed between the U.S. representative Benjamin Hawkins and the Cherokee Indians at the plantation of Andrew Pickens on the Seneca River in northwestern South Carolina. The treaty laid out a western boundary where white settlement would not be allowed to expand. ARTICLE V. If any citizen of the United States, or other person not being an Indian, shall attempt to settle on any of the lands westward or southward of the said boundary which are hereby allotted to the Indians for their hunting grounds, or having already settled and will not remove from the same with six months after the ratification of this treaty, such person shall forfeit the protection of the United States, and the Indians may punish him or not as they please… ARTICLE XII. That the Indians may have full confidence in the justice of the United States, respecting their interests, they shall have the right to send a deputy of their choice, whenever they think fit, to Congress. Questions: 1. Who are the parties to the Treaty and when was it passed? 2. How does this Treaty protect Indian Lands? 3. What rights do the Cherokee have if the terms of the Treaty are violated? 26 Document 2: Fifth Amendment to the US Constitution, 1791 Fifth Amendment - Rights of Persons & Property No person shall be…deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just [fair] compensation. Guiding Questions: 1. What does the Fifth Amendment say about private property? About property rights? 2. How might the Fifth Amendment connect to the Indian Removal Act? Does it support it or not? Document 3: Jackson’s Message to Congress, 1830 President Jackson’s Message to Congress “On Indian Removal” December 6, 1830 It gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly thirty years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements, is approaching to a happy consummation [conclusion]. The consequences of a speedy removal will be important to the United Sates, to individual States and to the Indians themselves…It puts an end to all possible danger of collision between the authorities of the General and State Governments, on account of the Indians. It will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters. By opening the whole territory between Tennessee on the north, and Louisiana on the south, to the settlement of the whites, it will incalculably strengthen the southwestern frontier, and render the adjacent States strong enough to repel future invasion without remote aid. It will relieve the whole state of Mississippi, and the western part of Alabama, of Indian occupancy, and enable those States to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power. It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from the power of the State; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way, and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay…and through the influence of good, counsels…To cast off their savage habits, and become an interesting, civilized and Christian community. Guiding Questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. According to Jackson, what are the benefits of removal for the Cherokee? According to Jackson, what are the benefits of removal for the United States? How does Jackson reconcile benefits to all the parties? What are the “common” benefits? Find examples of “loaded terms” Jackson uses to persuade Congress to his point of view? 27 Document 4: Senate Debate on Indian Removal Act, 1830 Excerpts from Senate Debate on Indian Removal Bill, April 16, 1830, Senator Peleg Sprague (Maine), 1830 By several of these treaties, we hare unequivocally guaranteed to them that they shall forever enjoy: 1st. Their separate existence, as a poetical community: 2nd. Undisturbed possession and full enjoyment of their lands, within certain boundaries, which are duly defined and fully described; 3rd. The protection of the United States, against all interference with, or encroachments upon their rights by any people, state, or nation. For these promises, on our part, we received ample consideration--By the restoration and establishing of peace; By large cessions of territory; By the promise on their part to treaty with no other state or nation; and other important stipulations. Whither are the Cherokees to go? What are the benefits of the change? What system has been matured for their security? What laws for their government? These questions are answered only by gilded [showy/glib] promises in general terms; they are to become enlightened and civilized husbandmen. …It is proposed to send them from their cotton fields, their farms and their gardens; to a distant and an unsubdued wilderness. To make them tillers of the earth! To remove them from their looms, their work-shops, their printing press, their schools, and churches, near the white settlements; to frowning forests, surrounded with naked savages. That they may become enlightened and civilized! We have pledged to them our protection and, instead of shielding them where they now are, within our reach, under our own arm, we send these natives of a southern clime to northern regions, amongst fierce and warlike barbarians. And what security do we propose to them? A new guarantee!! Who can look an Indian in the face; and say to him; we, and our fathers, for more than forty years, have made to you the most solemn promises; we now violate and trample upon them all; but offer you in their stead another guarantee!! Guiding Questions: 1. Is Sprague in favor of or against Indian Removal? How do you know? 2. What benefits did Sprague list about previous treaties to all the parties? 3. According to Sprague, how will the lives of the Cherokees change if they move west of the Mississippi River? 4. How does Sprague describe the change in communities or in Federal Indian Policy that will result from passage of this bill? 28 Document 5: Indian Removal Act of 1830 Indian Removal Act of 1830 (excerpts) An Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states of territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That it shall and may be lawful for the President of the United States to cause so much of any territory belonging to the United States, west of the river Mississippi, not included in any state of organized territory, and to which the Indian title has been extinguished, as he may judge necessary, to be divided into a suitable number of districts, for the reception of such tribes of nations of Indians as may choose to exchange the lands where they now reside, and remove there; and to cause each of said districts to be so described by natural or artificial marks, as to be easily distinguished from every other. Guiding Questions: 1. What kind of connections can you make between the Louisiana Purchase and Indian Removal to lands west of the Mississippi River? 2. What is the Act’s expectation of Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River? 3. Hypothesize what the impact of Indian Removal would be on tribes west of the Mississippi River. 29 Document 6: Great Heroes of Real Estate Great Heroes of Real Estate Guiding Questions: 1. Whose picture is on this Twenty Dollar Bill? 2. How does this image connect the person with the Indian Removal Act? 3. What do you think is the significance of the stamp: "Great Heroes of Real Estate"? Who do you think it refers to? 4. Do you think this artist would have supported the Cherokee’s rights to keep their land, or Jackson’s Indian Removal Policy? Explain why. 30 Document 7: Worcester v. Georgia (1832) Worcester v. Georgia 1832 Background: In this case, the plaintiff, Samuel Austin Worcester, Postmaster of New Echota (the Cherokee capital), appealed his conviction under a Georgia law that required all whites living in Cherokee Territory to obtain permission from the State. Worcester and seven fellow missionaries refused to obey the law. They believed that, because of their support for Cherokees who were organizing to resist removal, they would never be granted permission by the State of Georgia, the defendant in this Supreme Court case. Excerpts from Court ruling: From the commencement of our government Congress has passed acts to regulate trade and intercourse with the Indians; which treat them as nations, respect their rights, and manifest a firm purpose to afford that protection which treaties stipulate. All these acts, and especially that of 1802, which is still in force, manifestly consider the several Indian nations as distinct political communities, having territorial boundaries, within which their authority is exclusive, and having a right to all the lands within those boundaries, which is not only acknowledged, but guaranteed by the United States. . . The Cherokee Nation, then, is a distinct community, occupying its own territory, with boundaries accurately described, in which the laws of Georgia can have no force, and which the citizens of Georgia have no right to enter but with the assent of the Cherokees themselves or in conformity with treaties and with the acts of Congress. The act of the State of Georgia [defendant] under which the plaintiff in error was prosecuted is consequently void, and the judgement a nullity. . . . The Acts of Georgia … are in direct hostility with treaties, repeated in a succession of years, which mark out the boundary that separates the Cherokee country from Georgia; guarantee to them all the land within their boundary; solemnly pledge the faith of the United States to restrain their citizens from trespassing on it; and recognize the pre-existing power of the nation to govern itself. They are in equal hostility with the acts of Congress for regulating this intercourse, and giving effect to the treaties. Judgement reversed. Guiding Questions: 1. Did the Court rule in favor of the plaintiff or the defendant? What reasons are cited for the ruling? 2. How does this ruling define the Cherokee and what reasoning does it use to do so? 3. What previous laws are referenced about the rights of the Cherokee as a sovereign nation? 4. What did the ruling say about the rights of the State of Georgia regarding the Cherokee? 31 Document 8: Cherokee Land Maps (1791-1838) Teacher Note: Print this in color so the boundary lines are clear. Red boundary line indicates Cherokee land. Cherokee Land Maps-Original Claims, 1791, and Before Indian Removal 1838 Guiding Questions: 4. Use an atlas and identify which present day states the Cherokee lands were located in for the various time periods. 5. What is happening to the Cherokee land over time? 6. Based on the boundaries of the Cherokee lands in 1838, why might Georgia be the state most active in pursuing Indian removal? 32 DBQ Rationales for Documents Document: The Removal Act of 1830 (M/H) This document provides students with an opportunity to read the actual Removal Act document and what it says about Native Americans. It reflects the position of the United States government and the power it executed on the people and the land. Document: Worcester v. Georgia 1832 This is a court case between the state of Georgia and a citizen of Vermont that was punished by law for interactions he had with the Cherokee. It provides juxtaposition about how different types of interactions between the Cherokee people and citizens of the US were interpreted by various branches of the US government (the Supreme Court in this case). Document: Timeline of Cherokee Removal 1838 This timeline is a very helpful document for students to see the series of events that took place leading up to and including the forced march to Oklahoma. It presents different emotions for the Cherokee and the American Citizens. It also presents information about the actual conditions the Cherokee faced during that period. Document: Twenty Dollar Bill/Indian Removal Act of 1830 This document provides the students with an opportunity to look at a form of political commentary. There are words and images that will require the students to try and see the bigger picture. Document: Fifth Amendment Text 1789 This document will provide the students with the opportunity to evaluate how the Fifth Amendment was or was not applied to the Indian Removal Act. Document: Jackson’s Message to Congress 1830 This document will allow students to actually read the words Jackson spoke to Congress in regard to Indian removal. The students will be able to analyze and evaluate the language that Jackson used to present the Indian Removal Act. Document: Senate Debate on Indian Removal Bill, April 16, 1830, Senator Peleg Sprague (Maine) This document will allow students to explore the earlier treaties that were made with the Cherokee and dissent from Congress in how the treaties were not being followed by the US government. The senator that is speaking in this document is defending the rights of the Cherokee. Document: Cherokee Land Maps – Original Claims, 1791, and Before Removal 1838 These maps are a very clear way for students to see how the lands of the Cherokee really diminished over time. Students will be able to compare these lands with the present day states that occupy the lands. They will hopefully be able to connect the tension between the Cherokee and the State of Georgia in particular. 33 Document: Trail of Tears, The Legend of the Cherokee Rose This is a poem written from the point of view of a Cherokee about their experiences on the Trail of Tears. This document will evoke emotion and provide the students with a deeper insight into the personal experience of the Cherokee. Document: Treaty of Hopewell with the Cherokee November 28, 1785 This document will show the students that there were previous treaties between the Cherokee and the United States. The treaties explained how the land was to be used and repercussions for improper use. 34 Indian Removal Drama Script Shall We Leave Our Land? 35 Shall We Leave Our Land? CHARACTERS NARRATOR: Provides context for the characters and some background information. MAJOR RIDGE: Influential and wealthy Cherokee that supports removal. JOHN RIDGE: Son of Major Ridge. JOHN ROSS: Principal Chief of the Cherokee, wants to fight removal. LEWIS CASS (Secretary of War) SETTING Late January, 1835. Washington DC. Late evening. Play takes place in the Major Ridge’s sitting room. Candles are lit around a large wooden table in the middle of the room. The room is otherwise dark. SCENE ONE (Slide in backdrop shows a historic map of designated Indian Territory.) NARRATOR In January 1835, several meetings took place in Washington D.C. between the leadership of the Cherokee Nation and representatives of the U.S. Government. The purpose of these meetings was to decide how to proceed with Cherokee removal. Some factions within the Cherokee leadership advocated complete acceptance of the relocation plans seeing no other alternatives. Others factions wanted to delay removal until perhaps more advantageous terms may be negotiated. John Ross. 45 years old. 7/8th Scottish, 1/8th Cherokee, Principal Chief of the Cherokee nation for 7 years. A member of the Cherokee elite. (ROSS steps forward, turns and sits at the head of the large table, raises arm in a gesture, but appears frozen in space.) Pathkiller the 2nd. Also known as Major Ridge. 64 years old. 3/4 Cherokee, 1/4 Scottish, a plantation owner. One of the wealthiest men in the Cherokee Nation. (M.RIDGE steps forward sits down next to ROSS, looks at him intently, appears to be frozen in space.) John Ridge. 42 years old. Son of Major Ridge. Educated in a mission school in Georgia and later in Connecticut. (J.RIDGE steps forward and walks behind a chair around the table. He rests his hands on the back of the chair and turns toward the two other men, he also appears frozen.) (After J.RIDGE assumes his stage position, the NARRATOR steps off stage, the backdrop slide fades out and actors unfreeze. A serious discussion ensues.) 36 M. RIDGE I thought the same way as you for many years. I hoped that our great nation may remain on our ancestral homeland, side by side with whites. We became civilized. Our children went to mission schools. We settled down, became farmers. We did everything the Americans told us we had to do, but now I see no other way for our survival than to move to Oklahoma Territory. We sign the treaty. With our compliance, our people will survive. ROSS Major, I do not doubt your sincerity and love for our people, but you know as well as I that according to our laws, any Cherokee who sells their land to settlers is a criminal and will be put to death. J.RIDGE (jumps up and angrily faces ROSS) Is the Principal Chief threatening my father? ROSS No one is above our laws and the matter of our ancestral homeland is most sacred. M.RIDGE (gestures to J.RIDGE to sit down, turns to ROSS) Faced with the power of the federal government, we have no hope. The laws that you put such faith in are no more than words on a paper. The Supreme Court of the United States ruled for us in the past and this President did not enforce the law. I have seen that the power is with the President, we must comply with his wishes or our people will perish from this earth. ROSS Removal has been the law since 1830, but this government has been waiting to proceed. We must remain united in our cause. You saw what happened to other tribes; the Choctaw and Chickasaw leaders were broken. Some of them signed treaties that others rejected. But we have been united for so long. If no Cherokee leader puts their name to a treaty, we will have more time. Even this President won’t act without a treaty. J.RIDGE Georgia has already seized our land. It will continue to do so without interference from the President. Our fighters are no match for the state militia. Our efforts in Congress and the Supreme Court have been in vain. Relocation is the only way and we must proceed with it at once. No more delays; no more petitions. ROSS You both know as well as I, our people will not accept that. I do not accept it. We still have support in Congress. Honorable men in the U.S. Senate have supported us in the past. Mister Clay and Mister Webster. Men of good judgment have lent support to our just cause. And Andrew Jackson will not live forever. 37 M.RIDGE President Jackson is no friend to the Cherokees. Our National Council will not vote for relocation and our time is running out. We have to accept the lands beyond the great river or face the fate that befell so many other great nations. J.RIDGE The Principal Chief must act before it is too late. My father is correct. Our people simply don’t know what is waiting for them. We are their representatives. We must save them. ROSS I trust in the wisdom of our people and the righteousness of our cause. I do not agree with you. We still have time. (Knock on the door, the actors turn toward the sound and freeze.) NARRATOR (steps onto the stage) Lewis Cass. U.S. Secretary of War. A personal representative of President Jackson. (NARRATOR leaves stage. CASS enters room. He removes his heavy overcoat and places it on a chair. The other characters are still frozen. CASS pulls out a chair, the other characters unfreeze and stand up.) ROSS Mr. Secretary, I am surprised to see you here at such an hour. What brought you here? CASS Gentleman... (CASS motions to all to sit down, they all sit.) Our negotiations in the past few days, led the President to believe that some of you are ready to sign the treaty. ROSS Respectfully, Mr. Secretary, our National Council must ratify a treaty of such grave consequences for our people. No Cherokee would… (interrupted by M.RIDGE) M.RIDGE Some brave Cherokees are willing. (ROSS looks at M.RIDGE with an angry, bewildered expression and rises from the table and looks away.) 38 CASS (looks at M.RIDGE) The President and I have anticipated this. An additional twenty million dollars is offered by our government to help with the costs of moving your people. ROSS No Cherokee has the power to surrender our homeland without the vote of our National Council. This treaty will not be valid. Those who sign it are traitors to the Cherokee people. CASS (turns toward the M.RIDGE, ignoring ROSS) Major Ridge, you are a wise leader. You see things clearly. A man of reason and good judgment. The papers will be ready for your signature soon. ROSS Any Cherokee leader who signs such a treaty disgraces himself. CASS Mr. Ross. As you know Congress voted on the matter long ago. Your intransigence serves no purpose. ROSS I will not be a party to this shameful act of betrayal. (ROSS attempts to leave the room, M.RIDGE stands up to block his path to the door.) CASS Let Mr. Ross go. (ROSS exits the room.) CASS Gentleman, I will see you both tomorrow evening. I praise your good sense and judgment. (CASS leaves the room, J.RIDGE and M.RIDGE both stand up as he exits.) J.RIDGE Our people will understand, if we explain to them after we sign the treaty that there is no other way. A new opportunity awaits us in our new homeland. M.RIDGE I will speak to the Council after our return. I will explain that these were the best terms we could hope for. I know it will be hard to leave our homeland, but our nation will be saved. 39 (J.RIDGE and M.RIDGE turn to the projector screen backdrop and look up. Trail of Tears Google Map video appears on projector, map zooms in on the route, birds eye view flight over the trail of tears landscape plays slowly while the narrator reads the closing lines ) NARRATOR Ridge and his supporters signed the treaty of New Echota in December 1835. Their households moved willingly to west of the Mississippi. John Ross tried to delay removal, but eventually all Cherokees were forced to leave by the United States army. Thousands died on the trail, from hunger, disease and exposure to the bitter cold. In June 1839, Major Ridge, John Ridge and some of their associates were assassinated by people close to the Ross faction. END 40 Indian Removal Map Backdrop 41 Indian Removal Additional Classroom Activities 42 Additional Classroom Activities as Extensions for this Unit 1. Create murals of the journey the Indians took on the Trail of Tears. 2. Pretend you are a Cherokee child and write a letter to a family member expressing your emotions about your experience on the Trail of Tears. 3. Pretend you are a 30 year old US citizen farmer that lives in Georgia during the Indian Removal Act. Write a letter to a family member expressing your opinions on the act. 4. Research the most common types of foods that were consumed by the Cherokee. What were the means for growing and gathering food? How did it change when they were “moved” to a different place? 5. Role play the debate between Cherokee leaders and the American government. A useful website with primary source documents to evaluate is located at: <http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/teachers/lesson5cherokee.html> 43 Indian Removal Annotated Bibliography 44 Annotated Bibliography (DBQ Documents) Document: Indian Removal Act of 1830, A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 – 1875, Statutes at Large, 21st Congress, 1st Session. Retrieved from http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=004/llsl004.db&recNum=458 On May 26, 1830, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 was passed by the Twenty-First Congress of the United States of America. After four months of strong debate, Andrew Jackson signed the bill into law. It provided for “voluntary” resettlement of tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the Mississippi River. Document: Worcester v. Georgia 1832. Retrieved from http://www.civicsonline.org/library/formatted/texts/worcester.html Supreme Court case involving Worcester who worked and resided with the Cherokee and refused to obey a recently passed Georgia law prohibiting "white persons" from residing within the Cherokee Nation without permission from the state. Justice C.J. Marshall issued the majority opinion. In the court case Worcester v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court held in 1832 that the Cherokee Indians constituted a nation holding distinct sovereign powers. Although the decision became the foundation of the principle of tribal sovereignty in the twentieth century, it did not protect the Cherokees from being removed from their ancestral homeland in the Southeast. Document: The Cherokee Trail of Tears Timeline 1838. Retrieved from http://www.wishop.com/history/indian/trailoftearstimeline/trailoftearstimeline.htm Month by month timeline of events associated with the Trail of Tears during the year 1838. Document: Great Heroes of Real Estate: Indian Removal Act of 1830. Retrieved from http://www.docstoc.com/docs/2132124/The-Indian-Removal-Act-of-1830Cartoon of Jackson twenty dollar bill with a stamp of the slogan listed above. Document: U.S. Constitution: Fifth Amendment. Retrieved from http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/data/constitution/amendment05/ Fifth Amendment to the Constitution sets forth the due process and takings clauses. Document: President Jackson's Message to Congress "On Indian Removal", December 6, 1830; Records of the United States Senate, 1789-1990; Record Group 46; Records of the United States Senate, 1789-1990; National Archives. 45 On December 6, 1830, in a message to Congress, President Andrew Jackson called for the relocation of eastern Native American tribes to land west of the Mississippi River, in order to open new land for settlement by citizens of the United States. Document: Senator Peleg Sprague, Senate Debate on Indian Removal Bill, April 16, 1830. Retrieved from http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/teachers/lesson5-groupb.html#sprague Speech by Senator Peleg of Maine, who opposed the Indian Removal Act. The Act was faced with strong opposition and passed the Senate by just one vote. Document: “Treaty at Hopewell with the Cherokee Nation.” The Library of Congress American Memory Collection 31 Jan 1786. 24 April 2007 Retrieved from http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/bdsdcc:@field(DOCID+@lit(bdsdcc18101)) The Treaty at Hopewell defined the Cherokee’s boundaries by selecting an area of land by the rivers that flow around it. It also guarantees the Cherokee Nation’s independence from state governments. The treaty states that the US government would not come to the aide of white squatters and recognized tribal authority. Document: Cherokee Land Maps – Original Claims, 1791, and Before Removal 1838. Retrieved from http://www.cherokeehistory.com/original.gif; http://www.cherokeehistory.com/cne1791.gif; and http://www.cherokeehistory.com/cne1838.gif Sequence of maps showing Cherokee Nation lands from prior to European settlement through Indian Removal. Document: “The Trail of Tears,” poem. Retrieved from http://www.docstoc.com/docs/2132124/The-Indian-Removal-Act-of-1830-Questions Poem from the point of view of a Cherokee walking the Trail of Tears. 46