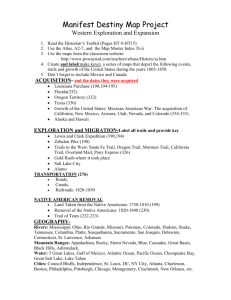

trail of tears national historic trail additional routes

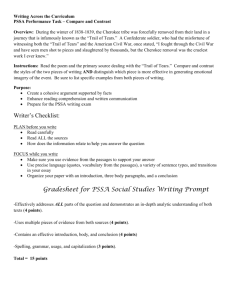

advertisement