S-330 Appendix C - International Association of Fire Chiefs

advertisement

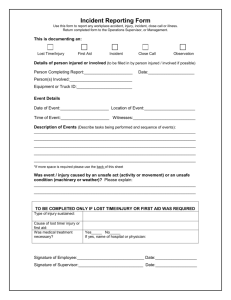

APPENDIX C PRE-COURSE WORK PRE-COURSE QUIZ PRE-COURSE QUIZ KEY C-1 C-2 TASK FORCE/STRIKE TEAM LEADER, S-330 Introduction to Pre-Course Work The pre-course work for the Task Force/Strike Team leader course is composed of two articles and a quiz. Article #1: Standard Firefighting Orders – discusses the reasoning behind the NWCG decision to return to the original format of the Standard Firefighting Orders. Article #2: Decision Support Briefing Paper (Levels of Engagement and DRAW-D) – provides a method to approach tactical engagement. The quiz will test your knowledge of material presented in courses prerequisite to this course, along with your familiarity with the Fireline Handbook and the Incident Response Pocket Guide. The quiz consists of 115 possible points. Students must achieve 70 percent or higher (81 points = passing) to be accepted into the course. Students will need to bring a current Incident Response Pocket Guide PMS 461 and Fireline Handbook PMS 410-1 to the course. C-3 Article #1: Standard Firefighting Orders The following is quoted from a February 25, 2003 memorandum from the National Wildfire Coordinating Group to the NWCG working teams. The original ten Standard Firefighting Orders were developed in 1957 by a task force commissioned by the USDA Forest Service Chief Richard E. McArdle. The task force reviewed the records of 16 tragedy fires that occurred from 1937 to 1956. The Standard Firefighting Orders were based in part on the successful “General Orders” used by the United States Armed Forces. The Standard Firefighting Orders were organized in a deliberate and sequential way to be implemented systematically and applied to all fire situations. The reorganization of the Orders was undertaken in the late 1980’s to form an acronym (“Fire Orders”), thus changing the original sequence and consequently, the intent of the orders as a program and logical hazard control system. Upon joint recommendation of the NWCG Training, Safety & Health, and Incident Operations Standards Working Teams, NWCG approved the restoration of the original ten Standard Firefighting Orders, with minor wording changes, at the May 22-23, 2002 meeting in Whitefish, Montana. We feel this change back to the original intent and format will improve firefighters’ understanding and implementation of the ten Standard Firefighting Orders. Please ensure this information is passed on to all your fire management personnel. Many fire managers noted over the last several years that firefighters of all qualifications were taking actions on fires that did not apply their fire behavior training and experience based on observing wildland fires. The following letter from Jim Steele and John Krebs provided the motivation to return to the original Standard Firefighting Orders. C-4 Over the past several years our attention to safety paradigms has become more a checklist tool to measure our failures than to successfully guide firefighters through a safe assignment. We are continually told to pay attention to the fundamentals, yet our understanding of many fundamental tasks is poor to non-existent. Rarely do we check to be certain firefighters understand standards and application of our widely accepted safety paradigms. When we have an opportunity to embrace a series of safety paradigms that exist with order and purpose, it is truly important that we fully understand the reasons and purpose. Each geographic area has benefited from individuals that grew up in the profession when it was young, and the workforce relied on standup common sense and lots of physical labor to be safe and successful. John Krebs, a Fire Behavior Analyst and recently retired Fire Management Officer from the US Forest Service, Clearwater National Forest, Idaho, is such a person in the Northern Rockies. For years he has helped us understand the application of the original Standard Firefighting Orders. I don’t think many of us fully understand the reasons behind the sequence of these orders. John recently explained this process in a letter. My interest in fire behavior, particularly in relation to fireline safety, has not diminished with time. I’ve had an opportunity to stay involved in fire with three fire assignments in 1996 and 1998, as well as participating in a couple of the National Fire Behavior workshops put on by the Region. Having just finished reading Maclean’s “Fire on the Mountain” I was again brought to tears at the tragic and senseless loss of those precious lives. The 1994 National FBA workshop included a visit to Mann Gulch. As we sat overlooking those 13 crosses our thoughts were that this kind of event would not happen again because our knowledge of fire behavior and our emphasis on training had greatly improved. How wrong we were! Where have we failed to make fire behavior the most important thought in the minds of our fire fighters when they are actually engaged in the suppression activity? C-5 Looking back to my first guard school training in 1958, I recall that the “10 STANDARD ORDERS” formed the framework for much of the teaching. The people who developed those original orders were intimately acquainted with the dirt, grime, sweat and tears of actual fireline experience. Those orders were deliberately arranged according to their importance. They were logically grouped making them easy to remember. First and foremost of the Orders dealt with what the firefighters are there to encounter “the fire.” 1. 2. 3. Keep informed on fire weather conditions and forecasts. Know what your fire is doing at all times. Observe personally, use scouts. Base all action on current and expected behavior of the fire. Each of the ten Standard Orders are prefaced by the silent imperative “YOU”, meaning the on-the-ground firefighters the person who is putting her or his life on the line!!! My gut aches when I think of the lives that could have been spared, the injuries or close calls which could have been avoided, had these three Orders been routinely and regularly addressed prior to and during every fire assignment! As instructors and fire behavior analysts have we become so enthralled with our computer knowledge and skills that we’ve failed to teach the basics? One does not have to be a full-blown ‘gee whiz’ to apply these Orders – they revolve around elementary fuels-weather-topography. These are things that are measurable and observable, even to the first year firefighter. When we went out as a fire team and were ‘briefed’, it was our responsibility to seek answers to basic questions – the first being, “What is the weather forecast?” Following that were questions concerning what the fire was doing, where it was expected to go, and how was it to be confined, contained, and/ or controlled. Every firefighter is entitled to ask and receive answers to these same inquiries. I should re-word that every firefighter should be “required” to ask....” C-6 Logically following these three fire behavior related orders were three dealing with fireline safety: 4. 5. 6. Have escape routes and make them known. Post a lookout when there is possible danger. Stay alert. Keep calm. Think clearly. Act decisively. One cannot know if an escape route or a safety zone is adequate until the Orders addressing fire behavior have been specifically evaluated. One of the primary functions of a lookout is observing and monitoring the weather and fire behavior. How can it be that some of our most highly trained and experienced fire personnel can be on a fire such as South Canyon and not record even one, on-the-ground weather observation? Where did we as trainers go wrong? I have a nephew who jumped out of McCall. Shortly after the South Canyon tragedy, I asked him if he ever carried a belt weather kit. His answer shocked me, “Uncle John, we don’t have room for those things.” Please tell me that has changed…. If humidities (reference Fire on the Mountain) were as low as 11% at 2400 hours on July 5, just what were they doing on the afternoon of July 6 on the western drainage? How can a firefighter possibly “Keep informed on fire weather conditions...” without on site monitoring of relative humidities, wind, etc. The next three 10 Standard Orders centered around organizational control: 7. 8. 9. Give clear instructions and be sure they are understood. Maintain prompt communications with your men, your boss, and adjoining forces. Maintain control of your forces at all times. Again, if one hadn’t properly considered the first three fire behavior related orders, it would be impossible to think that Orders 7, 8, and 9 could be addressed with any validity. C-7 The last of the 10 Standard Orders is: “Fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first.” This is the only Order which I would change just slightly to “Fight fire aggressively having provided for safety first.” Read Maclean’s account (pg 65) concerning what should be the last order “as they chanted the ten basic fire orders in training, the first order ‘Fight fire aggressively, provide for safety first’ becomes transformed into ‘fight fire aggressively, provide for overtime first.’” I can remember helping to teach some of the fire behavior (and related) courses in Missoula and asking the participants to write down all of the Fire Orders they could recall. There were students in S-390 (and higher) who could not recall more than 3 or 4 orders!! But, they always remembered, “Fight fire aggressively.... It was encouraging for me to learn from some first year firemen that they were required to learn the FIRE ORDERS in guard school. My fear is that this was merely an exercise in rote memory, as Maclean’s account would indicate. It’s something to chant but it is an exercise without memory. I urge you to re-establish the original 10 Standard Orders. They were developed in a very special order of importance, grouped to make practical sense, and most importantly when considered prior to and during every shift they will save lives. The 18 Situations that Shout Watch Out; LCES; Look up, Look down, Look all around; etc., are merely tools to reinforce the thought processes initiated by the original 10 Standard Orders. If we diligently read and believe the compendium of fatality and shelter deployment investigations, you will discover the commonality of failed tactics; they were implemented without adequate attention to fire behavior and the effects of fire behavior. C-8 FIRE ORDERS is the sequence that was devised to assist firefighters to remember the original Standard Firefighting Orders. As John points out, the revised edition becomes an “exercise in rote memory.” The original were designed as a decision process that guided tactics and firefighter attention to fireline safety. The focus was fire behavior. Please take the time to reconsider how you plan and implement tactical deployments and how you manage fireline safety through risk assessment and mitigation. Use the original 10 Standard Orders, in sequence, as a decision making process and verify the standards for each component: Is the weather forecast current and applicable to where you are? Do you have current information on the fire, and can you get it? Are weather and fire predictions accurate – this part is not rocket science! Are escape routes located, timed, and trigger points established allowing for the travel times you know your people can travel? Are you certain your safety zone locations are known, sizes verified, and of effective size? Are your lookouts able to see all of the area you want monitored during times you want? Are your lookouts safe? Can your lookouts communicate and do they know to whom, what to report, and when? Do you feel confident you have enough information to safely manage your resources against the fire? Is the radio your only means of communication? Do you have the background to handle a situation of this complexity; how comfortable do you feel right now? I share this with you because this is one of the first times I have heard the often used war cry, “back to the basics,” where the basics were explained. May 11, 2000 Jim Steele Northern Rockies Training Center, Missoula, Montana C-9 Article #2: USDA Forest Service National Wildland Fire Operations Safety Decision Support Briefing Paper Date: March 19, 2003 Topic: Levels of Engagement and DRAW-D Background: In response to the Thirtymile tragedy, the term “disengagement” was added to the wildland firefighting lexicon. As with many well-intended actions in response to identified needs, application and meaning of the term were all over the map. In the most severe of misinterpretations “disengagement” resulted in abandonment of suppression objectives by on-scene firefighters, rather than a shift in the level, breadth, or focus of their efforts. In order to clarify and emphasize the original intent (i.e., thoughtful and mindful decision-making and action in response to changes in the environment and the associated risk and exposure), an alternative descriptor is necessary. Key Points: 1. As with military field actions, there are only five things we can do in firefighting. We will call them LEVELS OF ENGAGEMENT: • Defend (holding actions, priority protection areas) • Reinforce (bringing more or different resources to bear on the issue) • Advance (anchor and flank, direct or indirect attack) • Withdraw (move to a safety zone or otherwise cease current activities until conditions allow a different level of engagement) • Delay (waiting until the situation has modified sufficiently to allow a different level of engagement) The Marine Corps calls this DRAW-D. C-10 2. DRAW-D concurrently applies to actions on segments of line, Divisions, or the incident in its entirety. 3. DRAW-D applies to the levels of fires we fight (initial attack, extended attack, large fires, and “mega” fires). 4. DRAW-D presupposes every action on or in response to an incident represents a level of engagement. Safe and effective firefighting requires a bias for action, realizing every tactical maneuver is predicated on thoughtful, mindful decision-making. In this model, accurate situational awareness, rapid and pinpoint risk identification and mitigation, and effective decision-making are essential. Decision to Be Made: Whether or not to introduce LEVELS OF ENGAGEMENT and DRAW-D in the firefighter lexicon, and pursue incorporation of the concept into firefighter training in general. Recommendation: Firefighting requires a bias for action. The environment is dynamic, risk-filled, and consequence severe. Every tactical action should be predicated on prompt hazard recognition and rapid decision-making. In this model “can-do” is incorporated in every level of engagement, and every level of engagement is equal in value to the overall effort as the other. Understanding this premise serves to channel firefighter cultural “can-do” bias toward effective, safe actions. It also serves to highlight the fact that any level of engagement or action requires a conscious decision based on the situation at hand or eminent. Withdrawal is not a stigma, but a decision. Delay is not a lack of effort, but a wise choice to maximize long-term effectiveness. Reinforcement is not a sign of weakness, but an indicator of savvy risk management. Adoption of LEVELS OF ENGAGEMENT and DRAW-D will help get our firefighters to the point of making the right decision, at the right time, with plenty of time to act. Contact: Ed Hollenshead, National Fire Operations Safety Officer, (208) 387-5102, ehollens@fs.fed.us C-11 Levels of Engagement Defend Hold and improve the line. Reinforce Add resources necessary to advance or defend. Advance Direct or indirect attack or active burnout operations. Withdraw Abandon constructed line or established position in response to fire behavior or other influences adversely affecting the ability to advance or defend. This may or may not include travel along safety routes to safety zones. Delay Wait for conditions to meet pre-identified triggers necessary to advance or defend. C-12 Task Force/Strike Team Leader, S-330 Pre-Course Quiz (115 possible points, 81 points = passing) Name:________________________ Score:___________ Answers to the following questions may be found by reviewing the NWCG courses that are required or suggested training for the position (S-230, S-215, S290, S-260, L-280), Incident Response Pocket Guide, Fireline Handbook, NWCG 310-1 Wildland and Prescribed Fire Qualification System Guide, and the Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology. 1. You need to find your transportation to the designated drop point. Who would you contact? a. b. c. d. 2. It is important for the Task Force Leader to be familiar with the capabilities of: (select all that apply) a. b. c. d. 3. Situation Unit Communication Unit Supply Unit Ground Support Unit Engines Crews Equipment Aircraft List at least three references for firefighting safety guidelines. C-13 4. It is the responsibility of the Task Force/Strike Team Leader to ensure the _____________ of their assigned incident personnel. a. b. 5. The __________________contains tables which provide line production rates for various resources under given conditions. a. b. c. d. 6. True False Your strike team crew and several other strike teams are being delivered to a mountain top by helicopter to a lengthy spike camp assignment. What two specialized positions would you anticipate being there to support your crews? a. b. c. 8. Incident Response Pocket Guide NWCG Fireline Handbook 410-1 Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology Both a and b In steep, rocky terrain a Type 1 dozer strike team will construct 3 times as much fireline in one hour as a Type 2 dozer strike team in 3 hours. a. b. 7. Fitness level / ROSS status Qualifications / Certifications Helispot manager and camp manager Facilities unit leader and camp crew Line EMT and a base camp manager While modifying tactics, which of the following must be considered? a. b. c. d. Matching resource capability with task The current and expected fire behavior Local factors influencing the weather All of the above C-14 9. Prior to receiving an assignment, what information is available from the previous operational period’s Incident Action Plan? (list 5 items) 10. As a task force leader you may have contract resources assigned to you. List at least three items that must be inspected prior to putting these resources to work. 11. List at least three items that must be inspected for agency resources, prior to putting these resources to work. 12. As a strike team leader of hand crews, what precautions would you take to control the issuing of equipment from the Supply Unit? 13. As a strike team leader you should try to sleep your resources in the same area. Who should you talk to if the incident camp map is not posted and you are not sure where the crew sleeping area is? C-15 14. Who should attend the operational briefing with you and how many Incident Action Plans should you acquire? 15. What are the three categories in structure protection triage? 16. List four hazards which present a threat during structure protection. 17. Engines engaged in structure protection should keep at least _ of water in their tanks. 18. The minimum adequate clearance around a structure is _______ feet. 19. If you encounter a Hazardous Materials incident, what should be your initial actions? C-16 gallons 20. What does this symbol mean when it is found on a building near the entrance? a. b. c. d. The structure is safe to enter. The structure is safe in some areas. The structure is not safe. Search and rescue team has left this structure. 21. List at least five important considerations to re-evaluate during the operational period. 22. What level of authority is required to authorize a backfire operation? a. b. c. d. 23. What level of authority is required to authorize a burnout operation? a. b. c. d. 24. Division/Group Supervisor Operations Section Chief Incident Commander Task Force Leader Single Resource Boss Strike Team Leader Division/Group Supervisor Operations Section Chief Give three examples of non-wildland fire (all-risk) uses of a task force. C-17 25. You are assigned as a Strike Team Leader-Crew (STCR) for a Type 2 hand crew strike team made up of various local agency firefighters. You are assigned to support operations during the initial attack of a rapidly growing wildland urban/interface fire. What are some steps you would take before deploying your crews? 26. Your crew strike team is having problems maintaining direct line construction because fireline intensities are too high. No aviation resources are assigned to your division at this time. You have not been able to contact your division supervisor. Using the ICS structure, which aviation function do you contact for support? a. b. c. d. Helicopter pilot Air tactical group supervisor Air support group supervisor Air tanker pilot 27. Describe the steps to be taken when addressing serious fireline injuries. 28. When completing forms involving claims for lost, stolen or damaged property, what incident personnel should the crew boss coordinate with? a. b. c. d. e. Division/Group supervisor Compensation/Claims unit leader Security manager All of the above a and c C-18 29. Who has responsibility for completing crew time reports? a. b. c. 30. The three wildland fire leadership values are: a. b. c. d. e. 31. Hazard assessment LCES Situation awareness Hazard control Decision point The risk management process is: a. b. c. d. 33. Duty Accountability Communication Respect Integrity What is the foundation of the risk management process? a. b. c. d. e. 32. Each individual crew person The squad bosses The single resource boss A one time action. Applied only when hazards are encountered. A continual process. Performed only by safety officer. You are given a fireline assignment that you consider unsafe. What fire management tool provides the protocol to properly refuse the risk? a. b. c. d. Interagency Helicopter Operations Guide Incident Response Pocket Guide Incident Action Plan Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology C-19 Use the Emergency Equipment Shift Ticket to answer questions 34-35. 34. The contract dozer assigned to your task force worked from 0630 until 1930 today. During the shift, the dozer ran out of fuel making it unavailable for 45 minutes. There is no daily guarantee in the contract and they are not required to show a lunch break. Complete the Emergency Equipment Shift Ticket. 35. The transport for your dozer was ordered to remain on the incident at a drop point in case the dozer was needed on another division. Each vehicle has its own agreement number. You record the equipment time for the transport: a. b. c. d. On the same shift ticket as the dozer. Make a note on your unit log. On a separate shift ticket. Ground Support will complete the transport’s time. C-20 36. You are on a Type 3 incident. The private water tender supporting your engine strike team is doing a good job, but doesn’t appear to have been inspected, since it has a cracked windshield and broken tail lights. What should you do? 37. You have discovered that two of your crew members have been smoking marijuana. Describe your responsibilities to your crew and as a supervisor. 38. A new crew arrives in camp and takes two lunches. Your crew goes to supply and there are not enough lunches. What steps would you take to resolve this situation? 39. Upon arrival at the incident you are told to go to Division B and meet with the division supervisor (DIVS) Susan Hickman on road No. 211 at the Beaver Dam. What do you do? a. b. c. d. Get supplies and head for the dam. Ask for a map. Request a complete briefing and a current IAP. a and b C-21 40. Name two assignments that the crew boss may need to plan for other than handline construction. 41. When constructing fireline using MIST tactics, what are the appropriate actions that would best facilitate site rehabilitation? a. b. c. d. Flush cut stumps, stockpile debris for scattering over site later, use natural barriers, avoid archeological sites. Flush cut stumps, scatter all the debris at least 100 feet from site, build roll trenches, build water bars. Ensure that nobody walks back over completed fireline. Let a resource specialist determine the actual line specifications. 42. As a crew boss, you evaluate firefighters on the line for: (list two) 43. Define the “DRAW-D” levels of engagement: D R A W D 44. __________ __________ __________ __________ __________ Whenever possible, _______________________ is used in fireline construction to minimize necessary rehabilitation efforts, without compromising firefighter safety. C-22 45. Topography most influences fire behavior by: a. b. c. d. 46. Fire is burning in litter on top of the ground, but occasionally carries into the crowns of individual trees, which produces burning embers that start new fires outside the fire perimeter. Choose the correct fire behavior sequence that fits the activities described. a. b. c. d. e. 47. Crown fire with convection column and firewhirls. Running wind-driven fire with active crowning. Crown fire with flare-up and torching. Ground fire with smoldering and flare-ups. Surface fire with torching and spotting. As air sinks, it: a. b. c. d. e. 48. Causing heavy fuel loading on southern aspects. Increasing stability throughout the atmosphere. Directly modifying general weather patterns. Decreasing flame lengths and rate of spread as slope increases. Rises in pressure, cools and expands. Lowers in pressure, warms and compresses. Lowers in pressure, cools and expands. Increases in pressure, warms and compresses. Increases in pressure, warms and expands. Wind direction is: a. b. c. The direction the wind is blowing toward. The direction the wind is blowing from. Not important for firefighters to know. C-23 49. Local winds are best defined as: a. b. c. d. 50. Air flows clockwise around low pressure systems and counterclockwise around high pressure systems. a. b. 51. Fuels are preheated upslope through radiation and convection. Rolling firebrands ignite new fuels below. Drier sites are more prevalent on steeper slopes. a and b Select the statement that best describes the effect of slope steepness on fuel availability. a. b. c. d. 53. True False Slope affects fuel availability to burn because: a. b. c. d. 52. Small scale convective winds of local origin caused by differences in heating and cooling. The wind measured at the 20-foot level and is a result of the general wind. The wind measured at eye-level and is a result of the general wind. A large scale wind caused by a high pressure system. A fire starting at the base of a slope has more fuel available for spread. Fuel beds on the upper third of the slope are always denser and more continuous. Fuel beds on south and southwest aspects usually are drier. All of the above. The four fuel groups defined in the Fire Behavior Prediction System (FBPS) are: a. b. c. d. Grass, shrub, timber litter, and logging slash. Grass, weeds, forbs, and timber litter. Perennial, shrub, timber litter, and logs. Weeds, grass, timber litter, and logs. C-24 54. Select the fuel complex that would reach its moisture of extinction first during nighttime humidity recovery of 20%. a. b. c. d. 55. What weather processes can and should be monitored visually? a. b. c. d. e. 56. Forecasts issued to determine spotting potential on large fires. Forecasts that are issued to update television and radio forecasts. Forecasts that are issued to fit the time, topography, and weather of a specific location. Initiate action based on: a. b. c. d. 58. Thunderstorm buildups Clouds Approaching cold fronts Indications of stable or unstable air All of the above Spot Weather Forecasts are: a. b. c. 57. Heavy slash, no attached needles Cured cheatgrass Chaparral shrub Palmetto gallberry Current fire behavior Expected fire behavior Current and expected fire behavior Weather En route to a fire you notice that smoke from a burning haystack rises straight up. What could this indicate on a wildland fire: a. b. c. d. An inversion may reduce the fire activity. An unstable atmosphere may increase fire activity. The relative humidity will be low. No information can be gained from the rising smoke. C-25 59. Four factors that are responsible for the occurrence of fire behavior in the third dimension are: a. b. c. d. 60. High fuel moistures, wind, low atmospheric moisture, and instability. Available fuels, wind, high atmospheric moisture, and instability. Available fuels, wind, low atmospheric moisture, and instability. Available fuels, wind, low atmospheric moisture, and stability. Which of the following is an indicator of stable air? a. b. c. d. Clear visibility Gusty winds and dust devils Inversion Thunderstorm development C-26 Task Force/Strike Team Leader, S-330 Pre-Course Quiz Key (115 possible points, 81 points = passing) 1. You need to find your transportation to the designated drop point. Who would you contact? (1 point) a. b. c. d. 2. It is important for the Task Force Leader to be familiar with the capabilities of: (select all that apply) (1 point) a. b. c. d. 3. Situation Unit Communication Unit Supply Unit Ground Support Unit Engines Crews Equipment Aircraft List at least three references for firefighting safety guidelines. (3 points) Agency manuals Interagency Helicopter Operations Guide NWCG Fireline Handbook 410-1 Incident Response Pocket Guide (IRPG) Emergency Response Guide (DOT orange book) 4. It is the responsibility of the Task Force/Strike Team Leader to ensure the _____________ of their assigned incident personnel. (1 point) a. b. Fitness level / ROSS Status Qualifications / Certifications C-27 5. The __________________contains tables which provide line production rates for various resources under given conditions. (1 point) a. b. c. d. 6. In steep, rocky terrain a Type 1 dozer strike team will construct 3 times as much fireline in one hour as a Type 2 dozer strike team in 3 hours. (1 point) a. b. 7. True False Your strike team crew and several other strike teams are being delivered to a mountain top by helicopter to a lengthy spike camp assignment. What two specialized positions would you anticipate being there to support your crews? (1 point) a. b. c. 8. Incident Response Pocket Guide NWCG Fireline Handbook 410-1 Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology a and b Helispot manager and camp manager Facilities unit leader and camp crew Line EMT and a base camp manager While modifying tactics, which of the following must be considered? (1 point) a. b. c. d. Matching resource capability with task. The current and expected fire behavior. Local factors influencing the weather. All of the above. C-28 9. Prior to receiving an assignment, what information is available from the previous operational period’s Incident Action Plan? (list 5 items) (5 points) • • • • • • • • • 10. As a task force leader you may have contract resources assigned to you. List at least three items that must be inspected prior to putting these resources to work. (3 points) • • • • • • • • 11. Weather forecast Fire behavior forecast Division objectives Special safety concerns Radio frequencies Travel routes/drop points Kinds and types of resources assigned to the incident. Map Other Contract or emergency equipment rental agreement. PPE Personnel experience Equipment inspection Certification of assigned personnel. Qualifications of assigned personnel. Demonstrated ability to communicate in English to the squad boss level and re-communicate in the predominate language of the crew. Document that the inspection occurred. List at least three items that must be inspected for agency resources, prior to putting these resources to work. (3 points) • • • • • • • PPE Personnel experience Equipment inspection Certification of assigned personnel Qualifications of assigned personnel Ensure resource(s) have appropriate radios/frequencies Document the inspection/briefing C-29 12. As a strike team leader of hand crews, what precautions would you take to control the issuing of equipment from the Supply Unit? (1 point) Assign one person from each crew to be responsible for their crew’s supplies. 13. As a strike team leader you should try to sleep your resources in the same area. Who should you talk to if the incident camp map is not posted and you are not sure where the crew sleeping area is? (1 point) The Base Camp Manger (BCMG), Facilities Unit Leader (FACL) or Logistics Section Chief if a BCMG or FACL is not assigned. 14. Who should attend the operational briefing with you and how many Incident Action Plans should you acquire? (1 point) Check with Plans to ensure there is enough room for each single resource boss, if so all should attend. Also check to make sure there are enough Incident Action Plans available and get one for each single resource boss. 15. What are the three categories in structure protection triage? (3 points) • • • 16. Needing little or no attention Needs protection Cannot be saved List four hazards which present a threat during structure protection. (4 points) • • • • • • Power lines Septic tanks Animals Hazardous Materials Drop offs Propane tanks C-30 17. Engines engaged in structure protection should keep at least 100 gallons of water in their tanks. (1 point) 18. The minimum adequate clearance around a structure is 100 feet. (1 point) 19. If you encounter a Hazardous Materials incident, what should be your initial actions? (4 points) • • • • 20. Stay upwind, uphill, and out of the smoke/fumes. Isolate and deny entry. Warn others in the vicinity. Notify your supervisor/dispatcher to start a proper response. (FLH p. 56, IRPG p. 24) What does this symbol mean when it is found on a building near the entrance? (1 point) a. b. c. d. 21. The structure is safe to enter. The structure is safe in some areas. The structure is not safe. Search and rescue team has left this structure. (IRPG p. 27) List at least five important considerations to re-evaluate during the operational period. (5 points) • • • • • • • • • • • Weather Effectiveness of assigned resources Meeting expected timeframes Fire Behavior Safety of resources Work with adjacent resources LCES Watchout Situations Standard Firefighting Orders Keeping up with necessary documentation Others? C-31 22. What level of authority is required to authorize a backfire operation? (1 point) a. b. c. d. 23. What level of authority is required to authorize a burnout operation? (1 point) a. b. c. d. 24. Single Resource Boss Strike Team Leader Division/Group Supervisor Operations Section Chief Give three examples of non-wildland fire (all-risk) uses of a task force. (3 points) • • • • • 25. Division/Group Supervisor Operations Section Chief Incident Commander Task Force Leader Search and rescue mission Structure fire Body and equipment parts recovery Mass-patient incident Planned activity You are assigned as a Strike Team Leader-Crew (STCR) for a Type 2 hand crew strike team made up of various local agency firefighters. You are assigned to support operations during the initial attack of a rapidly growing wildland urban/interface fire. What are some steps you would take before deploying your crews? (3 points) • • • Obtain a briefing from supervisor. Are they red carded, trained for their position (CRWB, FFT1, FFT2, FAL’s, etc.). Do they have necessary supplies and equipment to do the job (food, water, tools, etc.). C-32 • • • 26. Your crew strike team is having problems maintaining direct line construction because fireline intensities are too high. No aviation resources are assigned to your division at this time. You have not been able to contact your division supervisor. Using the ICS structure, which aviation function do you contact for support? (1 point) a. b. c. d. 27. Secure the scene and provide medical attention Notify supervisor Follow medical plan in the IAP When completing forms involving claims for lost, stolen or damaged property, what incident personnel should the crew boss coordinate with? (1 point) a. b. c. d. e. 29. Helicopter pilot Air tactical group supervisor Air support group supervisor Air tanker pilot Describe the steps to be taken when addressing serious fireline injuries. (2 points) • • • 28. Have they ever worked on a WUI incident before, or of this complexity? Others (allow some latitude in the answers). Deliver a briefing to assigned resources. Division/Group supervisor Compensation/Claims unit leader Security manager All of the above a and c Who has responsibility for completing crew time reports? (1 point) a. b. c. Each individual crew person The squad bosses The single resource boss C-33 30. The three wildland fire leadership values are: (3 points) a. b. c. d. e. 31. What is the foundation of the risk management process? (10 points) a. b. c. d. e. 32. Hazard assessment LCES Situation awareness Hazard control Decision point The risk management process is: (1 point) a. b. c. d. 33. Duty Accountability Communication Respect Integrity A one time action. Applied only when hazards are encountered. A continual process. Performed only by safety officer. You are given a fireline assignment that you consider unsafe. What fire management tool provides the protocol to properly refuse the risk? (1 point) a. b. c. d. Interagency Helicopter Operations Guide Incident Response Pocket Guide Incident Action Plan Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology C-34 Use the Emergency Equipment Shift Ticket to answer questions 34-35. 34. The contract dozer assigned to your task force worked from 0630 until 1930 today. During the shift, the dozer ran out of fuel making it unavailable for 45 minutes. There is no daily guarantee in the contract and they are not required to show a lunch break. Complete the Emergency Equipment Shift Ticket. (5 points) 35. The transport for your dozer was ordered to remain on the incident at a drop point in case the dozer was needed on another division. Each vehicle has its own agreement number. You record the equipment time for the transport: (1 point) a. b. c. d. On the same shift ticket as the dozer. Make a note on your unit log. On a separate shift ticket. Ground Support will complete the transport’s time. C-35 36. You are on a Type 3 incident. The private water tender supporting your engine strike team is doing a good job, but doesn’t appear to have been inspected, since it has a cracked windshield and broken tail lights. What should you do? (3 points) Inform your supervisor, document and situation will dictate whether you continue to work or stop working the tender. 37. You have discovered that two of your crew members have been smoking marijuana. Describe your responsibilities to your crew and as a supervisor. (3 points) • • • 38. A new crew arrives in camp and takes two lunches. Your crew goes to supply and there are not enough lunches. What steps would you take to resolve this situation? (5 points) • • • • 39. Document and gather evidence. Contact chain of command for possible personnel actions. Remove personnel from line until decision is made by command. Contact food unit leader Contact division group supervisor Contact crew boss of the new crew to clarify if they were instructed to double lunch. Contact supply to see if MREs are available for your crew. Upon arrival at the incident you are told to go to Division B and meet with the division supervisor (DIVS) Susan Hickman on road No. 211 at the Beaver Dam. What do you do? (2 points) a. b. c. d. Get supplies and head for the dam. Ask for a map. Request a complete briefing and a current IAP. a and b C-36 40. Name two assignments that the crew boss may need to plan for other than handline construction. (2 points) • • • 41. b. c. d. Rehabilitation Search and rescue Structure protection Flush cut stumps, stockpile debris for scattering over site later, use natural barriers, avoid archeological sites. Flush cut stumps, scatter all the debris at least 100 feet from site, build roll trenches, build water bars. Ensure that nobody walks back over completed fireline. Let a resource specialist determine the actual line specifications. As a crew boss, you evaluate firefighters on the line for: (list two) (2 points) • • • • 43. • • • When constructing fireline using MIST tactics, what are the appropriate actions that would best facilitate site rehabilitation? (2 points) a. 42. Firing operations Mop-up Coyote tactics Experience level (high or low) Hazardous attitude Fatigue Distracted from primary tasks Define the “DRAW-D” levels of engagement: (2 points) D EFEND R EINFORCE A DVANCE W ITHDRAW D ELAY 44. Whenever possible MIST is used in fireline construction to minimize necessary rehabilitation efforts, without compromising firefighter safety. (1 point) C-37 45. Topography most influences fire behavior by: (1 point) a. b. c. d. 46. Fire is burning in litter on top of the ground, but occasionally carries into the crowns of individual trees, which produces burning embers that start new fires outside the fire perimeter. Choose the correct fire behavior sequence that fits the activities described. (1 point) a. b. c. d. e. 47. Crown fire with convection column and firewhirls. Running wind-driven fire with active crowning. Crown fire with flare-up and torching. Ground fire with smoldering and flare-ups. Surface fire with torching and spotting. As air sinks, it: (1 point) a. b. c. d. e. 48. Causing heavy fuel loading on southern aspects. Increasing stability throughout the atmosphere. Directly modifying general weather patterns. Decreasing flame lengths and rate of spread as slope increases. Rises in pressure, cools and expands. Lowers in pressure, warms and compresses. Lowers in pressure, cools and expands. Increases in pressure, warms and compresses. Increases in pressure, warms and expands. Wind direction is: (1 point) a. b. c. The direction the wind is blowing toward. The direction the wind is blowing from. Not important for firefighters to know. C-38 49. Local winds are best defined as: (1 point) a. b. c. d. 50. Air flows clockwise around low pressure systems and counterclockwise around high pressure systems. (1 point) a. b. 51. True False Slope affects fuel availability to burn because: (1 point) a. b. c. d. 52. Small scale convective winds of local origin caused by differences in heating and cooling. The wind measured at the 20-foot level and is a result of the general wind. The wind measured at eye-level and is a result of the general wind. A large scale wind caused by a high pressure system. Fuels are preheated upslope through radiation and convection. Rolling firebrands ignite new fuels below. Drier sites are more prevalent on steeper slopes. a. and b. Select the statement that best describes the effect of slope steepness on fuel availability. (1 point) a. b. c. d. A fire starting at the base of a slope has more fuel available for spread. Fuel beds on the upper third of the slope are always denser and more continuous. Fuel beds on south and southwest aspects usually are drier. All of the above. C-39 53. The four fuel groups defined in the Fire Behavior Prediction System (FBPS) are: (1 point) a. b. c. d. 54. Select the fuel complex that would reach its moisture of extinction first during nighttime humidity recovery of 20%. (1 point) a. b. c. d. 55. Thunderstorm buildups Clouds Approaching cold fronts Indications of stable or unstable air All of the above Spot Weather Forecasts are: (1 point) a. b. c. 57. Heavy slash, no attached needles Cured cheatgrass Chaparral shrub Palmetto gallberry What weather processes can and should be monitored visually? (1 point) a. b. c. d. e. 56. Grass, shrub, timber litter, and logging slash. Grass, weeds, forbs, and timber litter. Perennial, shrub, timber litter, and logs. Weeds, grass, timber litter, and logs. Forecasts issued to determine spotting potential on large fires. Forecasts that are issued to update television and radio forecasts. Forecasts that are issued to fit the time, topography, and weather of a specific location. Initiate action based on: (1 point) a. b. c. d. Current fire behavior Expected fire behavior Current and expected fire behavior Weather C-40 58. En route to a fire you notice that smoke from a burning haystack rises straight up. What could this indicate on a wildland fire: (1 point) a. b. c. d. 59. Four factors that are responsible for the occurrence of fire behavior in the third dimension are: (1 point) a. b. c. d. 60. An inversion may reduce the fire activity. An unstable atmosphere may increase fire activity. The relative humidity will be low. No information can be gained from the rising smoke. High fuel moistures, wind, low atmospheric moisture, and instability. Available fuels, wind, high atmospheric moisture, and instability. Available fuels, wind, low atmospheric moisture, and instability. Available fuels, wind, low atmospheric moisture, and stability. Which of the following is an indicator of stable air? (1 point) a. b. c. d. Clear visibility Gusty winds and dust devils Inversion Thunderstorm development C-41 C-42