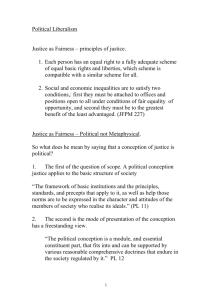

Justice as Fairness: Political not Metaphysical Author(s): John Rawls

advertisement