WPSA final - Western Political Science Association

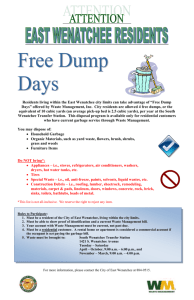

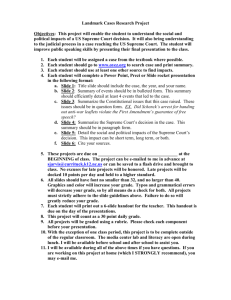

advertisement