Sentence Completion Test of Ego Development

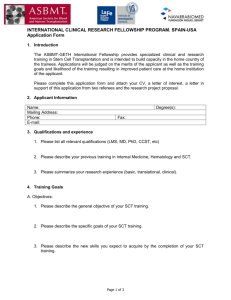

advertisement