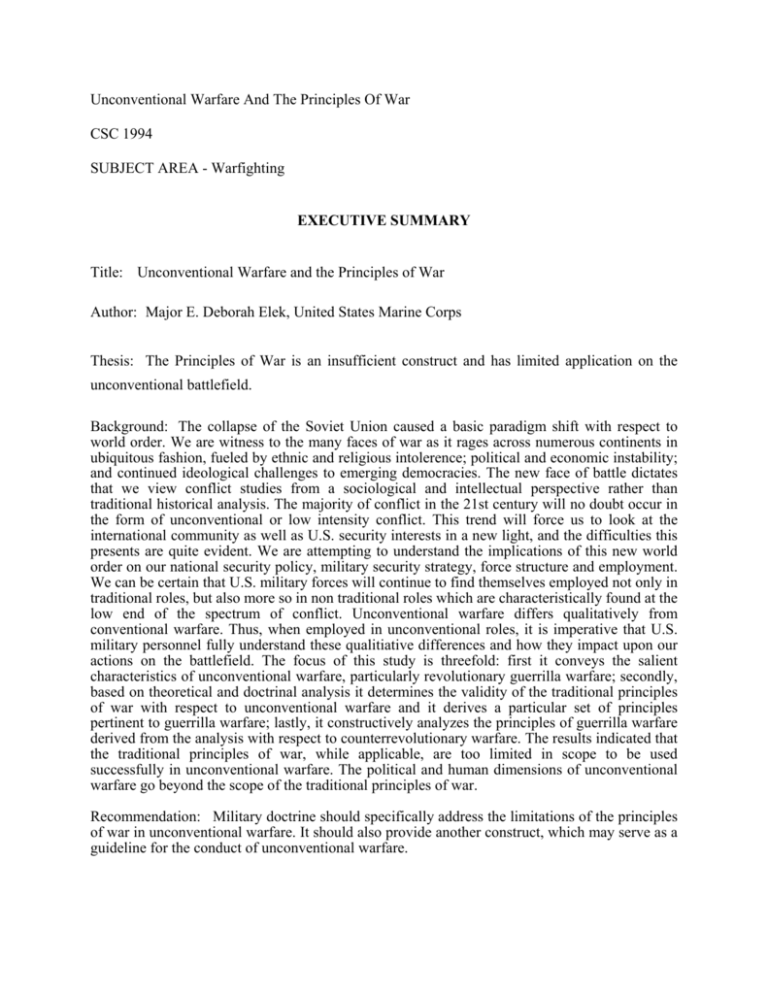

Unconventional Warfare And The Principles Of War

advertisement