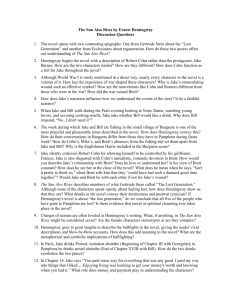

The Sun Also Rises author

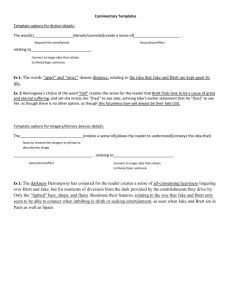

advertisement