City of San Antonio and Bexar County

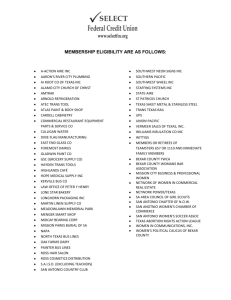

advertisement