John Steinbeck's Spatial Imagination in "The Grapes of Wrath": A

advertisement

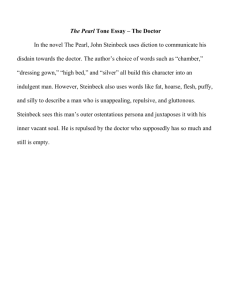

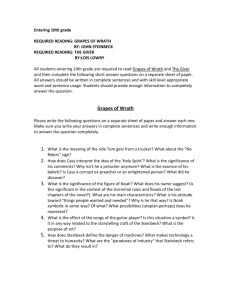

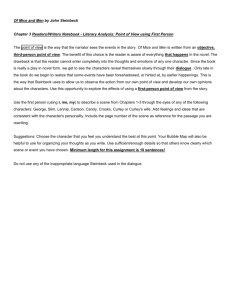

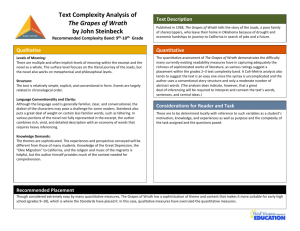

John Steinbeck's Spatial Imagination in "The Grapes of Wrath": A Critical Essay Author(s): George Henderson Source: California History, Vol. 68, No. 4, Envisioning California (Winter, 1989/1990), pp. 210 -223 Published by: California Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25158539 Accessed: 12/01/2010 15:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=chs. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. California Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to California History. http://www.jstor.org NQp* 4v^ \\\ \\a ^mMsI^^Ib1Sh~1Hk^ j^li^^^^B Dust-Bowl refugee migrant workers picking cotton in California during the 1930s. This illustration and others in this article are by the great American artist Thomas Hart Benton, from the Limited Editions Club edition of TTzeGrapes 0/Wnrtfc (1940). Courtesy The Limited Editions Club and the Steinbeck Research Center, San Jose State University 210 CALIFORNIA HISTORY III. Literary California John Steinbeck's The Grapes A CRITICAL of in Imagination Spatial Wrath: ESSAY by George Henderson Introduction: as Social Action. Representation ran "Harvest Gypsies," commissioned articles, by News winter of 1937-38 was especially wet in the San Joaquin Valley. Steady and heavy rains saturated the San Joaquin flood plain, partic The ularly in cotton-growing Madera County. ruary of that winter John Steinbeck wrote agent Elizabeth Otis: In Feb to his Imust go over into the interior valleys. There are families starving to death over about five thousand there, not just hungry but actually starving. The is trying to feed them and get medical government to them with the fascist group of utilities attention and banks and huge growers sabotaging the thing all along the line and yelling for a balanced budget. In one tent there are twenty people quarantined are to have for smallpox and two of the women I've tied into the thing babies in that tent this week. on from the first and Imust knock these murderers the heads. Do you know what they're afraid of? They think that if these people are allowed to live in camps with proper sanitary facilities, they will organize and that is the bugbear of the large land owner and the corporation farmer. The states and counties will give them nothing because they are But the crops of any part of this state outsiders. could not be harvested without these outsiders. I'm pretty mad about it. No word of this outside because when Ihave finished my job the jolly old associated (Steinbeck farmers will and Wallsten, be after my scalp again For several years Steinbeck had been eyeing the situation "interior rial writer (see St. Pierre, 79-81 for excerpts). In those brief pieces a reader could find most of the major themes about California agriculture that Steinbeck would later chronicle in The Grapes of Wrath in 1939. Shortly after "Harvest Gypsies" was printed, Steinbeck's Of Mice andMen and In Dubious Battle appeared in the bookstores. of migrant in the workers agricultural In 1936 San The October Francisco valleys." Battle was In Dubious selected by the Book of theMonth Club, and within a month one hundred thousand copies had been purchased. Both novels concerned costs the social and unique social formations that Steinbeck attri buted to the system of corporate agriculture in the valley (St. Pierre, 81). Thus, by the time Steinbeck began The Grapes ofWrath, his vision was keen and his hand well practiced. The new novel began to take on a spectacular life of its own. Six months after publication, two when hundred thousand copies had been sold, Common a book sells like wealth magazine noted that "when causes it and when comment and contro the that, a this it book cultural becomes has, versy phenom enon of important dimensions. and The literary critical industry of the country is not really geared to handle it" (quoted in St. Pierre, 98-101). The critic lamented the lack of attention to the book's literary merit. Most readers or not California 158). a series of Steinbeck's the paper's chief edito only wanted for example, (see Kappel, Kern County). Too much bad, had WINTER 1989/90 211 been to know whether resembled Steinbeck's depiction geared on the novel's ban in criticism, both good and to assessing the factual content and background of The Grapes of Wrath. Only in later years did the "pattern of criticism" turn to an assessment of the novel's to relationship themes, such as biblical allegory and the "Wagons the late thirties anyone who cared could During have the general corroborated Administration and Resettlement induced labor surplus, the migrant vigilantism tance if not events, the Hoovervilles details, provided by Steinbeck?the camps, crop specialization grower by region, trek from the Dust Bowl states, the and the relief work, and the impor of cotton as the new One of the devices by which though many contemporary California's agricultural production ago: thirty years out that "most of the Burke has pointed Kenneth is to say their characters derive their role, which to the their from personality, purely relationship But what he takes to be a serious basic situation." is actually one of the book's weakness greatest (Lisca, "The Grapes ofWrath as Fic accomplishments tion," a migrant 736). The Grapes ofWrath was indeed relentlessy didac apparently upon over observation the two writers did not collaborate. Al did, they did not need to refer to the novel in order to understand the historical reliance of much of infused with process. This point seems to lie behind Peter Lisca's and convincing In broadly prose, Mc supported a mirror text for Steinbeck's wrote Williams novel, readers Steinbeck content was to saturate this thematic an with of the his readers' minds understanding to that seemed formative processes genetic, push as to make in such a way the story along every character action part of an enveloping and every his work The release of The Grapes ofWrath could not have been better timed in relation to the publication of Carey McWilliams' Factories in the Field (1939). although landless inversion. crop. speculative in a rootless, authority class. The point, then, is that Steinbeck registered the duality of history and nature in terms of a social idiom. West" to vest moral dared but by ensuring tic, even formulaic, ers the involved processes grasped as the above quote would situation," that the read the "basic (or have it) Stein labor class. Yet The Grapes ofWrath did fulfill a role beck could then suggest how different orders of as a experience of virtue attachment text. and social realist interpretive regionalist as a document stands of social change. The novel more can be asked of it. Nonetheless, to turn to a itmight be interesting For example, problem of the human condition that Steinbeck apparently set up in The Grapes ofWrath. One of was concerns to repre fundamental Steinbeck's to families sent the migration of white midwestern as part of that recurrent condi human California itself condition that the human tion, while arguing and social is shaped historical contingencies. by He asked what relationship the laws of nature had nature does not tran to human-made situations: nor does scend or determine super history history, accounts I think, for the This sede nature. idea, charac of some of Steinbeck's immortal qualities ters. At the same time, only the historical moment, could reveal of social relationships, the intervention what might be enduringly will to survive?to humanize true: Ma Joad's heroic the natural survival threat. by economic only manifested in a tran belief ultimate and Casy's Tom Joad's was out only hammered human scendent family instinct?was by virtue of their ability to gauge just how far the local situation. had penetrated relations power and at demoralized Steinbeck's elevating adeptness to of level the beaten history epochal migrants social relations and inverting makers, by phrasing specifically themes, local questions fueled his detractors, in terms of grandiose who would not have and contained others by represented for example, the overarching causes; a wholesomeness to land represented of body and spirit.What also is inherently geographical turns tuting, out to be inherently social, both consti is and constitutive of, the same processes.lt from social and geographical relationships that rather than from an individual radiates, meaning or action. character were with In this way small details charged out and representing larger processes. bearing This seems a like just the sort of thing befitting philosophical argument of naturalism. But it should not be forgotten that itwas the modernization forms and its attendant of agricultural production of consciousness that, Steinbeck brought argued, in particular that aspect this state of affairs; about of modernization change technological whereby into contact loosens boundaries, formerly brings for a seem and allows discrete things and persons, ingly small event to be nested more significant. The particular inside something importance of the modernizing process as detailed by Steinbeck was that it foreshadowed (the power representation to grasp cognitively the rending and reshuffling itself as a precursor social bonds) of traditional for the dilemma to social action. A fundamental of their own daily the inappropriateness Joads was to an interpretation of the and practices thought was new order. Nowhere and economic political 212 CALIFORNIA HISTORY this contradiction more evident than in the end less bickering over the value of talking over their problems. Steinbeck himself took on the problem as the re of representation insofar interchapters as a narrated the story form of documentation. became Moreover, representation by the end of the novel both a narrative and a form of strategy social action. these general I want to explore Taking points, a how kind of they conferred imagina particular to Steinbeck's tive process of the The Grapes writing This orchestrated the geo of Wrath. imagination sites and the situation of characters de graphical in the novel, the particular social processes picted as across space, which they unfolded only people in the could have process swept up modernizing understood. Grapes ofWrath cannot be understood The unless the characters are seen fully to develop relationship to the places through which in they that they also reconstituted, if only to be a gen This approach is meant momentarily. one and not an argu eral, illuminating necessarily ment to be sustained for each character. Rather, the interpretative in the action addresses approach as a a novel Tom Since carries Joad totality. large moved?places proportion of the thematic load of the novel from such a perspective, the bulk of my discussion will focus on him. in geographical Steinbeck's terms, thesis, primary was on that you cannot understand is going what inside California unless is occurring you know what outside. out by the novel's This notion was borne concern with mapping the Joads' overwhelming across the western states. Given the fam migration a farm in Califor ily's goal of obtaining family-size that the Joads never nia, it could be argued really were where The migration got upon they going. which has no conclusion in the they embarked novel other than an ironic symmetry between begin and The in charted ning literary "map" ending. The Grapes ofWrath was finally not just a geographic product, important, but was then, laden with It is social meaning. to move the line of questioning away from how the Joads got from one place to the and by which toward how meaning next, routes, is produced, and disseminated with controlled, to we social and space. Also, regard workaday need to a to discover where general theory society. Specifically, Steinbeck geographic of place Steinbeck formation I would sat in regard in capitalist like to show how demonstrated his awareness of social/ as the outcome medium and the space of certain processes: the division of labor along class and gender lines; the territorial demands of capitalist agribusiness; and family and community space for their own produc and private These fulfillment. tion, reproduction, were the conditioned modern era, processes, by to appropriate needs to bear on the Joads' travails as they brought encountered the wider social world and it, in turn, or resisted received their arrival. In a sense my outlook as too be criticized may economistic. state at the onset Let me that I am some familiar with of the common cultural and ideological idioms of Steinbeck's work, including themyth of the garden, the family farm as a reformist ideal, and of women the closeness to nature. While Steinbeck appeared to have left these myths intact, and indeed to have relied upon them, he dismantled others of a specific local and regional character: the innocence of California's agricultural family farm as a basic unit the bounty, myth of an egalitarian frontier in theWest, of democracy. and the of Instead treating each of the above concepts explicitly, Iwill simply let them inform my thinking, drawing on as necessary or appropriate. I think, structured the meanings of the Steinbeck, in were which the book's characters situated places on two levels. took on meaning First, each place them through its dynamic relationship with an opposite kind of either real or imagined. the Second, place, interaction of these polarities or over transformed turned social relations. can two How "interact"? Contradictions places the processes of the division of labor, capi among talist agribusiness, and small social units arise as each asserts its territorial demands for space? to its very critical continuation?and the brings a novel's re and characters into dialectical places lationship. With acting places the notion of dialectically in mind, Iwould, sets of oppositions which typify the primary among These oppositions settings constitute then, posit inter three the relationships in The Grapes ofWrath. major literary devices through which Steinbeck represented the processes of the creation of space. The three social/geographic sets of oppositions are: 1. The tension between is power places where centered?or of socially represented?and places marginal 2. activity for peripheralized The contradiction between people; California as a visible, knowable, Edenic landscape and the Joads' invisibility and ignorance within it; 3. The conflict between divergent modes of transforming habitats. WINTER 1989/90 213 nature and producing humane fy> p.-. **>^^^^^^^^ '^SIISnH^H^^B '?^S^?^^^^^HHf n^^^l California growers' ofmigrant expl?ltation in the1930s was laborers mac*epossibleby support I' E^^lK^^W^il^^^H^^^^^filBBB I: .AxV%^^WMll^P^B^P^^9il9 L*W^J&Sr ^^^SPJrlP^il^MSi Mf iilKm ^K^h^^Sl^</P^Hi9 HtaflMH ^HH&BBPi?Ea^^HB| l#y^t vCH^mP^^^^#^^1HHI^B Bfctttp^^ig HP^^fj/ LimitedEditionsClub V^V^^HH ^ Jn ^rompublic authorities. In ^s lustrationfromthe editionof TTie Grapes ofWrath ^^^r^^B^R J^ HsSbdJHMfslHL'""* Portraysa state policeman ?9^91 HHH^^SW^IK^ ^^^SBLJVmH ^^^^^HflV^HB^x^N^B^iB^^H^ ^^^^^^^H JHH&MBflPSMb'-W?^ ^^^^^^^^^^^^HH^^Kjj^Hp^^&UH ^^^^^^^HHH^^SS^H^^RL SflP^P ^^^^^^^^H^H^^vJljR^ ^^^^^^|Hi^^^^^H^pPJ^^|y^Q ^^^^^^HN^^^^^HR^bHP t^P^Hi ^^^^^l^B^^^^^MEsM^^HL^J^MI Places ofCentralized Power andMarginalized Activity. The of power geography and disenfranchise ment is relatively straightforward in The Grapes is drawn of Wrath. A primary distinction towns between and banks, on hand. The damental implication, antagonists the one which the fun comprised was in Steinbeck's book, that finance capital, fixed in places and the entrenched and hand, camps on the other Routes 66/99 and the migrant urban settlement both hostile to the "independent" (the banks), pattern were and dispossessed rural smallholder and migrant worker. Oklahoma on small to foreclose banks extended their domain or mid-size towns California resisted farms, while the onslaught were of the displaced migrants. Migrant thus pushed from two directions: from their homelands and away from the away small-town of the farmers and merchants. sanctuary and town-dwellers alike Bankers, farmers, big families feared that the Joads would find a place inwhich to lenged and ^a^n8theJoac* familytruck. Thepolicewereassisting Tulare Countyfarmers by "scabs"through convoying setupbystriking picket fieldworkers.Courtesy The LMtedEditions Clubandthe Steinbeck Research San Center, JoseStateUniversity rivaled the exclusive claims to authen ticity held by the historically validated, pre-existing in which moral and pattern, authority were in fixed centers, vested either power political towns or farms. Steinbeck reversed and this notion settlement a vision of moral purity and impending political power as they were taking shape on the outlined road: The cars of the migrant people crawled out of the side roads onto the great cross-country highway, and they took the migrant way to the West. In the to scuttled like westward: the daylight they bugs and as the dark caught them, they clustered like . . . Thus it bugs near to shelter and to water might be that one family camped near a spring, and another camped for the spring and for company, and a third because two families had pioneered the the sun went place and found it good. And when families and twenty cars down, twenty perhaps were there. into power, whereas up belong. Fixity translated was rootedness the best assurance of continued disenfranchisement. From this point, Steinbeck wrote what might be called a drama of settlement. in the The settlement drama has two dimensions a reinvention In one, Steinbeck novel. of imagined a natural, formed the organic society exigencies by a strange In the evening the thing happened: one families became the children twenty family, . were the children of all ... es that make a world, Every night relationships torn down the world tablished; and every morning like a circus . . . gradually the technique of build worlds became their Then leaders ing technique. then laws were made, then codes came emerged, . . into being .(p. 264-5). Roadside." Steinbeck of the highway This life along new, the "Great American transitional society both chal 214 CALIFORNIA HISTORY wrote into the situation a sort of moral Yet the modernization. ous status in the novel. time as it restrained. was simply that the basic social rules, forgotten by proposed socially nots. A was gle overlaid era West: Route 66 was anew. This be learned resisted those who were by the have haves the against well-placed: and medium for this strug manifestation form of social the new relations spatial on the of the new, depression landscape the dominant society, was change must a circular California a narrow way the great fantasy is in the to foretell a day of revolution, passages succeeding unforeseen interests because by large propertied were an "I" frame of mind, in still not yet they into communal liberated consciousness. a The author presented of fragmentation pattern portentous regrouping this role is transformed on the road. from nemesis toward a The road to necessity, for all its for house search and gar came to, they made they down 99. It is Route escape numbers content to reveal themselves their sym south on "99" (p. 384). Turning to "66." The Joads were the route number on the same but home, essentially high that used to lead to their old front door. The Joads' Invisibility and Ignorance within a Visible, the raising of individualized forms of conscious ness to the level of class. Steinbeck wrote that "one one from the land." The man, [is] driven family . . . and bewildered." is "alone But single migrant then something Two men meet, "squat happens. on their hams and the women and children lis ten. . . ." This Steinbeck out, meeting, pointed is the "mode" of revolution. T lost my "Here " . . . our land' is changed 'We lost land.' [to] (p. of the rural freeholder class which moved pre-dawn inverted far from social its laws had been because revised leveler, to accommodate lives as lived on the road. In the new the trucker was the benefactor. landscape, was of the new Steinbeck enamored roadside culture?the the truckers, the truckstops diner, as he ridiculed its transgressors?the fee ?just cars the salesmen used campgrounds, peddling for ill-gotten profits. the reasoning "Hooverville" the route Edenic continued in their path yet it led the Joads down den. After the Joads' scrape with the law in the first bolic over at this point in the novel, was one over legacy, over historical notion of the "free" authenticity, land in the West. out culture stretched Migrant into a great protective net across the roads of the was west. No land the democratizing ele longer 206). Steinbeck consciouness, tempting to think that Steinbeck was manipulating The struggle towhich Steinbeck implicitly alluded, of the settlement for the formation of the symbolic and cultural weight, 267-8). The other dimension social logic of road maintained ambigu It beckoned at the same essential new migrants' The families, which the had been units of which were a house at night, a farm by day, boundaries In the long hot light, their boundaries. changed were cars in silent the they moving slowly west ward; but at night they integrated with any group they found. as Thus they changed their social life?changed man can in the whole universe only change. They were not farm men any more, but migrant men (p. ment. Rather, geographical mobility was is to follow the contradictory if history on the of American borne regeneration society, At backs of its most members. first, beleaguered a "circus", a the new society but it seemed parody, in Landscape. critical juncture in the book arrived as the Joads were astride the top of the Tehachapi A Mountains, looking over out the Central Valley toward Bakersfield. They had just endured the disappointment of Needles ("Gateway to Cali fornia"), a funeral procession through theMojave Desert, and the agricultural inspection at station Daggett: Al jammed on the brake and stopped in the middle of the road, and, "Jesus Christ! Look!" he said. The the orchards, the great flat valley, green vineyards, and beautiful, the trees set in rows, and the farm . .The distant cities, the little towns in the houses. on the orchard land, and morning sun, golden . . .The in fields the valley grain golden morning, and the willow trees in rows. lines, the eucalyptus Pa sighed, "I never knowed they was anything like her." . . .Ruthie and Winfield scrambled down from the car, and then they stood, silent and awestruck, . .and Ruthie embarrassed before the great valley. "It's California" whispered, (p. 309-10). This moment, when of California, spectacle novel when the Joads they was took were the faced with in the foreshadowed a Nee outside respite dles. Tom Joad wondered then whether the image of California would pan out in reality: Pa said, "Wait till we get Tom try then." to California. admonished, You'll "Jesus see nice Christ, coun Pa! This here is California" (p. 278). Moments later Tom talked with aman versed in the subtler aspects of the California landscape. He told Tom what California, WINTER 1989/90 215 to expect, and although he was leaving he encouraged Tom to go see for himself: "She's a nice country. But she was stole a long time ago. You git acrost the desert an' come into the seen An' you never country aroun' Bakersfield. such purty country?all orchards an' grapes, pur tiest country you ever seen. An' you'll pass Ian' flat an' fine with water thirty feet down, and that lan's layin' fallow. But you can't have none of that Ian'. An' if they That's a Lan' and Cattle Company. don't want tawork her, she ain't gonna git worked. You go in there an' plant you a little corn, an' you'll go to jail!" (p. 279) The migrants rural paradise had seen draped of California?a pictures a snow with back capped ground (p. 271). In the scenes depicted Joads are image. to confront brought But even when the visible and above the question landscape that seemed to fit the pictorial myth, the social and economic reality had brutal implications. The landscape, a as presented spectacle, crest of the Tehachapis, between contradiction to the observer from the concealed the enveloping the subsistence of potential the soil and the monopolistic almost masochistic survival "crawl," of the asserted fortitude, their blind, (that evidence of the on animal bordering drive?bugs in the face the Joads "crawl") which flew instinct of everything tion. They were they had heard along their migra distrustful (p. 283). Indeed, Uncle John foresaw the truth of their expe in the great valley. rience seen any of the particular have been able to map out of "words" and Center, San Jose State University "talk": II BfetSBwylw Yet he could not have not and would features the continuation of their journey from the vantage point at the pass in the The crisis of representation here had Tehachapis. two expressions. One was the inability of the Joads were to convey to each other what they getting into. The other expression themselves of the crisis was the very landscape power that lay before them. The to represent of the landscape, future events as they would be shaped by social/power relations and to lend predictability to the migrants' lives, rapidly diminished. The landscape ambiguously revealed and concealed its contents. Joads had been making companies. the Joads large landowning Still, however, tendencies of Needles] [Uncle John by the riverbank outside "... We're ain't we? None of this there, a-goin' here talk gonna keep us from goin' there. When we get there, we'll get there. When we get a job we'll work, an' when we don't get a job we'll set on our tail. This here talk ain't gonna do no good no way" All along, the equation between the the visible and the possible, between reality and repre as sentation. The notions of "there" and "here" on a map, or as elements of the field of points vision that could be identified and reached, were continually obscured because the Joads were lured in the first place by the spectacle of California. Or, -^^Ejj^^ 216 CALIFORNIA HISTORY _^^EaL*^ was California spectacle. What rather, they as a to them revealed only in fact, was a parallel, found, though peripheralized, world. The apotheosis of the peripheral world was the A parody of the American small-town Hooverville. ideal and a continuation of Steinbeck's settlement could be found these settlements squatter myth, town: "The rag town outside of every "real" lay were to and and the houses close tents, water; a weed-thatched houses, enclosures, paper great junk pile" (p. 319-20). The "rag town" was really nothing but the discharge point of the effluvia of the social "a great order: junk pile." The descrip tion alluded to the flow of goods, but the Hoover a ville made of real economic mockery exchange. was And the The flow of goods uni-directional. were was tents settlement merely illusory?houses and paper constructions. Yet it was prehended plot in Hooverville that the Joads com the basic contradictions that drove the forward. followed The migrant camp on the outskirts the "mother of invention" dictum, but an essential the camp was instru geographical a in ment labor for concentrating region surplus where one extensively planted crop ripened all at a broad area. In Hooverville, Tom Joad is a to old hand about how lectured world-wise, by the gathering enabled of surplus workers employ ers to pay miserable them men wages. got "S'pose . . . Jus' offer kids 'em a nickel?why, they'll kill once over each other fightin' for that nickel." The men had been lured by handbills, and "You can print a hell of a lot of han'bills with what ya save payin' fifteen an hour cents instructor. He for fiel' work," continued: explained Tom's a big son-of-a-bitch of a peach orchard I in. Takes nine men all the year roun'." He "Takes three thousan' men paused impressively. . . them peaches is ripe. for two weeks when They send out han'bills all over hell. They need three . Whole . thousan', an' they get six thousan'. part a the country's peaches. All ripe together. When one is picked. ever' goddam ya get 'em picked, There ain't another damn thing in that part a the country to do. An' then them owners don' want ... So you there no more. they kick you out, they move you along. That's how it is" (p. 334r-5). "They's worked The California spectacle was revealed as a horrific production racket involving key combinations: a division of labor with a painfully seasonal and extensive spatial underpinning, mono-cropping, and the short term needs of migrant families individuals to keep together. Although porary arrangement the diurnal body and and soul was a tem any one Hooverville in the migrant Hoover world, to be found on the edge of every town. villes were Each was fragile over were extensive they time. Over geographical and threatening. Thus, space they had their hand in a dialectical turn of events: "every raid on a Hooverville, every deputy swaggering through a ragged camp put off the day a little and cemented the inevitability of the day [when the land will belong to the workers]" (p. 325). Just as the Joads were awed and (embar inspired rassed too) by the view of the landscape from atop vision of an ordered, owners world?the the Tehachapis?a tive, and beneficient produc of prop erty, the producers of that landscape and the image as of California a haven for the dispossessed, wished to keep the migrants moving. The land scape itself was to be a fixed, closed entity, and the was to keep idea of keeping the outcasts moving from thinking of them as part of the real picture. as a to define the laborer merely The point was means of the of production rather than as inheritor one of which rewards of an agrarian tradition, to the would be the very privilege of belonging landscape by being a landholder. Steinbeck a attached sciousness-historical Ironically, ship. understands the ses of dispossessed, But workers need form particular land knowledge?to it is the great landowner who that when there are mas lesson will follow. revolution surely to grasp their role in the histori cal process. How does the worker come into as Joads peasants "workers"? Wrath of con owner in The Grapes of that consciousness? that they know do the How have become The Joads were not ascribed any potential for social mobility. In addition, their spatial mobility was almost if not prescribed. restricted, thoroughly a into the self about a real Thus, plunge brought to history and society. In spatial ized relationship seclusion terms, chose places empowering as relations Characters was Steinbeck required. carefully a character a renewed and see to from which social point that gave vantage contradictions fraught with must be in a position placed (p. 571-2). from which to view their world upside down, with order reversed. Invariably, these ginal, both in the productivity hierarchy of human places the social were mar of nature and in the habitats. Divergent Modes of Transforming Nature and thePro duction ofHumane Habitats. tried to capture the historical place Steinbeck and time inwhich putting land into produc tionmeant different things to different classes of people. The primary event that set The Grapes WINTER 1989/90 217 was in motion the Joads' loss of their of Wrath on the prop to a bank homestead that foreclosed a fundamental drew distinction erty. Steinbeck a a between to their of spatial proximity people a land and, conversely, spatial disjunction: "Place where folks live is them Graves] [Muley out lonely on the road in a folks. They ain't whole, car. They ain't alive no more. Them sons piled-up " a-bitches killed 'em' (p. 71). The man [Later, a fragment from an interchapter] . on the earth, turning his plow who is . . walking to slide his handles point for a stone, dropping over an outcropping, to eat in earth the kneeling his lunch; that man who ismore than his elements the land that ismore than its analysis. knows But the machine man, driving a dead tractor on land he does not know and love, understands only chemis of the land and of try; and he is contemptuous the corrugated iron doors are shut, himself. When and his home he goes home, is not the land (p. 158). was very keen on the notion Steinbeck establishing on to that an emotional land relationship depends contact with close physical the soil. Because Muley Graves did not join the Joads, he failed to recog nize in the experience the opportunity for renewal was to rec of migration. he clever However, enough means a in the and of survival land ways ognize over to an alien of system given wholly agricultural In an early scene on the old Joad home production. stead, Muley explained to Tom and Casy the fine art of hiding in a land where there was supposedly nowhere to hide (p. 77-8). Cotton had been planted so extensively at the old farm that it likened flushing out the fugitives to looking for a needle in a hay stack. To a degree, field opposed their invisibility in the cotton the inability of the small farmer to on a real per of foreclosure pin the responsibility a stranger son. Each to the other. The side was as it them divided modern them, system brought together. Ultimately landholder's longer make system the small became farming" The small farmer could no a a crop. Under the land support extensive mono of modernized production, "tractor nemesis. cropping of cotton engulfed the Joads' farm. on the The Reverend Casy and young Tom stood hill and looked down on the Joad place. The small at one corner, and it house was mashed unpainted so that it had been pushed off its foundations an at its blind front windows angle, slumped at a spot of sky well above the horizon. pointing The fences were gone and the cotton grew in the dooryard and up against the house, and the cotton . . toward the grew close against it. They walked concrete well-cap, walked through cotton plants to get to it, and the bolls were forming on the cotton, and the land was cultivated (p. 54-5). In a number of such Steinbeck passages brought images of two rural orders together potent in The new all farm annihilated large cotton distinctions between various micro the no door of the Joad farm: no more fences, places no clear or to shed, outhouse, yard, path trough. even for There were no places that "proper weeds a should grow under The trough." "proper phrase seems weeds" like an oxymoron, yet gets the point across that the old rough and tumble homestead was a of and natural scheme. part good It was such a scheme that the Joads and others conflict. former dreamed of reproducing in their exile. The idea that land should be used and occupied, rather than left fallow, was stymied, however, by the power of the large landowner to let arable land remain idle: . . .And the along the roads lay the temptations, fields that could bear food. That's owned. That ain't our'n. we could get a little piece of her. Well, maybe little Maybe?a piece. Right down there?a patch. Jimson weed now. Christ, I could git enough pota toes off'n that little patch to feed my whole family! It ain't our'n. It got to have Jimson weeds (p. 320-1). to cultivate the "secret gardens" fail Any attempts the New ?unless Deal intervenes Out (p. 321). side of Bakersfield the federal government estab lished the migrant labor camp, Weedpatch. is reminiscent of both the "secret Weedpatch and the town" Hoovervilles. The gardens" "rag government camp even appeared was provided momentary respite, idyllic. Yet in the final analysis than a glorified little more not could the desire support humane habitat: sanitary facility for a permanent, it and Tom walked down the street between the rows of tents ... He saw that the rows were straight and that there was no litter about the tents. The ground . . . of the street had been swept and sprinkled Tom walked He neared Four Number Sani slowly. tary Unit and he looked at it curiously, an unpainted low and rough (p. 393). building, was the vector of several important Weedpatch in the novel. themes It drew on the idea of geomet as support ric orderliness and cleanliness for the town. Its moral of the American small authority a secure with resonated and bounded setting a It was rural propriety. from which the point of the migrant "folk" could emanate amidst power the enveloping of agribusiness. Most enterprise 218 CALIFORNIA HISTORY [ t? /^ST ' Ny|Ck'~"^****^fc. \ l f f~ f"ftJi*vM J \ j ^Zftfa. ^^^7 JfT^^''^"" was the overlapping space powerfully, Weedpatch of three "institutions": the short term needs of the federal relief policy, and large workers, migrant in its scale capitalist For all agriculture. importance these Weed however, systems bringing together, a a Itwas patch remained marginal place. holding area for the worker in a place where employment was scarce after the harvest. the migrant Inside, was and thwarted the strong community attempts a riot. to incite of local vigilantes Ultimately, itwas agribusiness that set the rules. The though, to leave like them were forced Joads and others and look for work. If the "secret garden" failed to sustain the myth of yeoman Steinbeck independence, experimented or cracks, in with that it is in the seams, the notion the agricultural in-between (the landscape places the process, rather than the final outcome, where can be viewed), of the appropriation of nature where the self can retreat and become empowered contact with nature, through fragmentary though it may be. In The Grapes of Wrath this idea was in the context of the agricultural expressed produc In this way in a tion process. Steinbeck located specific time and place what otherwise would an entailed notion. be He to explain took pains in and Oklahoma California farming and social control forms of subordination ahistorical that modern whole (p. 50-1; 316-20). Steinbeck's point, of course, was can be to suggest how these consequences resisted. In order to understand how these arguments in the novel, we can examine work events certain as occur in ditches and they irrigation hedgerows or cracks, ?two in the agricultural types of seams, seam that represent gaps in apparently landscape less power relations. Tom Joad, the primary character of the novel, two in The experienced baptisms irrigation ditches. a was first was performed Tom when by Casy boy a revivalist and Casy His first baptism preacher. did not mean too much to young Tom. Its meaning was became clear when Tom only re-baptized?this time by himself?after doing something out of and a sense conviction In this of social justice. were Tom's actions less blind, more than scene, was the result of the that he merely things always bumping into. Tom had just discovered Casy and a of other In a scuffle with labor organizers. of vigilantes who were them down tailing a stream, was killed. Tom struck down Casy fatally the killer, was himself his escape struck, and made up the embankment: number a group He bent low and ran over the cultivated earth; clods slipped and rolled under his feet. Ahead he saw the bushes that bounded the field, bushes WINTER 1989/90 219 along the edges of an irrigation ditch. He slipped through the fence, edged in among vines and black berry bushes. And then he lay still, panting hoarsely . . . .He lay still on his stomach until his mind came back. And then he crawled slowly over the edge of . . . the ditch. He bathed his face in the cool water. a The black cloud had crossed the sky, blob of dark against the stars. The night was quiet again (p. 527-8). This second "baptism" was more figurative secular than the first, but Steinbeck meant and them to events. In each instance be parallel Tom and Casy were case Tom's In each followed present. baptism some form of violence. The first baptism occurred too naive to lend any under conditions which were to Tom's life. The marked second, however, meaning into a period his passage of solitary resolve and was emanci moment the he For spiritual rekindling. . . . black cloud had crossed the sky. pated?"The oc That the baptisms The night was quiet again." was in irrigation consistent curred ditches simply with the setting of the story. Yet their location has to sites about of renewal and say something spiritual resistance in a space of seemingly total social control. The is an essential ditch feature and irrigation in a semi-arid instrument of agriculture environ ment. It is part and parcel of the transformation of and hence, of the production and labor nature, process (one of the few jobs Tom gets is digging an irrigation ditch). The ditch of the second baptism is at the field's edge, by water-seeking protected as it As much bushes. of the evidence represents over nature, dominant it remains class's mastery its own kind of environment, so elemental with water are unsullied. that its restorative The properties unlike the social and economic that water, system not is to it selective about whom it, manipulates gives life. The second and precursor margins environment to resistance, of solitary reflection, is the hedgerow at the of the cotton fields. Like the irrigation ditches these micro-environments the help build novel's architectural And symmetry. similarly they see Tom's movement from a state of partial denial to affirmation of his role in social change. Twice the reader finds Tom Joad hiding at the edges of cotton fields. The first time iswith Muley Graves at the Joads' old farm, when Tom and Casy follow Muley 220 CALIFORNIA HISTORY can stay the It turns to a place where night. they "... to be a cave in the bank of a water-cut. on the clean T ain't sand. himself Joad settled no cave,' he said. Tm gonna gonna sleep sleep in out right here.' He rolled his coat and put it under his head" (p. 81-2). Tom is in hiding despite his pride and delibera tions to the contrary, but he falls short of entering Tom's the cave as Muley does. The scene presages in a similar in California: future exile situation Muley warns Tom that he will be hiding "from lots of stuff." Tom himself dug the cave at the edge of he was the field when what more a youth "Lookin' appropriate place inwhich than California at the edge of a cotton for gold"? field. were at the time of (where they working comes true: death), Casy's Muley's prediction Al turned right on a graveled road, and the yellow over the ground. The fruit trees lights shuddered were gone now, and cotton plants took their place. They drove on for twenty miles [italics mine] through . . . The road a bushy creek the cotton paralleled and turned over a concrete bridge and followed the stream on the other side. And then, on the edge of the creek the lights showed a long line of red box and a big sign on the edge of the cars, wheelless; Al slowed road said, "Cotton Pickers Wanted." orchard . . . ". . . Look," he [Tom] said. "It says they want cotton pickers. I seen that sign. Now I been tryin' to figger how I'm gonna with you, an' not stay make no trouble. When my face gets well, maybe it'll be awright, but not now. Ya see them cars back the pickers live in them. Now maybe there. Well, work there. How if you get work there about they's an' live in one of the them cars?" "How 'bout you?" Ma demanded. "Well, you seen that crick, all full a brush. Well, I could hide in that brush an' keep outa sight. An' at to eat. I seen night you could bring me out somepin a culvert, little ways back. I could maybe sleep in there" (p. 550-1). Tom was While secure in the hedgerow above the creek by the cotton field, he could not only reflect on the recent events, but represent them to his mother in their fullmeaning. In his hiding place he found his kinship to a humanity beyond the family boundary, and came into a sense the distincion of overarching social purpose. Steinbeck intimated that Tom would follow in Casy's steps (p. 570). By repeating the hiding pattern established earlier in the novel, Steinbeck foreshadowed the internal in Tom's character. Steinbeck seclu change played sion and personal the geo empowerment against extensive and demoralizing graphically agricultural one worker between and is another, shown in The Grapes ofWrath to have enough cracks to individuate to allow certain people themselves. These cracks reflect on the contradictions of the unex idea of the process, sustaining production as a reserve nature for the human ploited spirit con during historically specific and dehumanizing ditions. Thus, Tom Joad had to be alone in a particu larkind of space, in a special relationship with nature, before he could realize that, after all, he is part of a social to end up After Tom escapes with this family from the peach down working conditions. The spatial reach of agribusi ness in the thirties, which seems to have levelled of an historical group, moment?before he could grant authority to the representational political value of language. The Grapes of Wrath Steinbeck In the values praise and and appeared unswerving to pragmatism of the migrant workers and families. Through Tom Joad, however, who finally discovered in his hideout that talking, thinking, and language are tools for understanding Steinbeck also criticized "common Joad family's discussion and the very idea of seemed overly precious. What the Joads needed worthy ments, of the practical predica the shortcomings in which sense," representation to recognize instead was the value of representation as learned ?not in myth, in the but as relearned kinds of spaces where the individual can represent first to himself, then to others, a version of reality closer to the truth. In order for the human family to unite, the boundaries of the nuclear family had to be Ma loosened. Joad's intact. She realized land, they "fambly" that, while a bounded, were not could remain her family had cohesive entity. With out it they were falling apart (p. 536). However, only through their disintegration would they really think and act beyond themselves. we Finally, are left to wonder how Steinbeck ultimately appraised the situation of the "Okie" migrant worker. To his credit Steinbeck did not see the migrant class as a monolith, ferentiated. For example, toward the novel Ma and Pa Joad have gender-based viewpoints. but rather as dif the conclusion of taken divergent, Pa became preoccupied with looking backwards, so nostalgic for a time when he was head of the household division of labor that he could not participate in the present. Ma was forward looking, acknowledging that the land in California was, after all, better than their Oklahoma farmland. She rose from the ashes of a burnt-out household, the vehicle for Steinbeck to expose the pitfalls of patriarchy. in the historical moment, WINTER 1989/90 221 Pa remained stuck if not in the past itself. Rose of Sharon, sister of Tom Joad, the leading character, in TTze Grapes of Wrath. One of the major themes in Steinbeck's novel was the manner in which economic inequality and exploitation undermined the status of who earned On "breadwinners." self-respect by being were to Steinbeck, less ego-involved women, hand, according more economic in touch with system, productive spiritual men, the other in and the life giving forces of nature, and thus more adaptable to adversity. Reflecting this theme, conclusion, child, suckled in the novel's heart-rending, enigmatic, Rose of Sharon, who had just suffered a starving strange man at her breast and controversial the still-birth of her in order to save his life. Courtesy The Limited Editions Club and the Steinbeck Research Center, San Jose State University 222 CALIFORNIA HISTORY as a woman, to changing situ readily adapted as a life "flow." the However, ations, accepting on are not to Pa Ma and based ascribed positions an ahistorical sense of masculine and feminine. For both Pa's nostalgia and Ma's philosophy of "flow" an histori were occasioned in their entrapment by Ma, cal and geographical flux. Itwas Ma, while still in attach first experienced Oklahoma, nostalgic ments. The tragedy of the migrants' there situation, so seems not to that much had leave fore, they who home, but that California did not yet offer the permanent place they thought it promised. Steinbeck took the view that migrant workers were in a complex of relations modernizing caught the western that the features of states, particular on the forms of their experience also depended consciousness and practice that they brought to and set that and rules situations, ideologies by modern also relied in part on a laboring capitalism class such as the Joads represented. I have sug gested division that Steinbeck was keenly aware that the of within agricultural production and the family farm, and capitalist agribusiness the consciousness of individuals and social groups, labor, all had requirements that grew out of and were projected onto contradicting geographical spaces. The particular sions, oppositional motifs, that I think Steinbeck used argument, were: the spaces of power a series of ten to convey his and disenfran chisement, the ambiguity of the landscape as a depicting and concealing agent, and the conflicting modes nature. of transforming were These motifs the means oppositional by which Steinbeck created a space for certain charac ters to resist the oppressing forces. The Joads were never power was not all completely marginalized; powerful. The attempts tomake the Joads invisible a cog in the in the process, landscape, production sense in some to their redemption. contributed was never nor subdued, Nature entirely mastered and itwas by virtue of its transformation class in power See "References" that beginning George Henderson gram in geography WINTER 1989/90 223 restorative gaps were by the left. S on page 262. is a graduate student in the doctoral pro at the University of California, Berkeley.