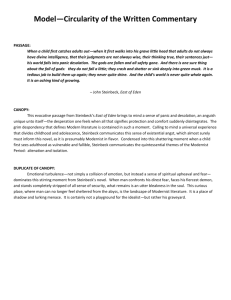

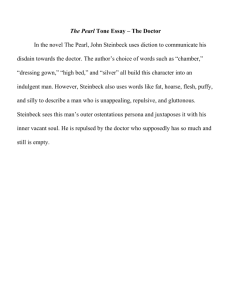

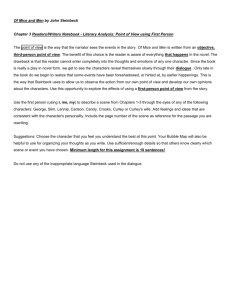

Basic Paper

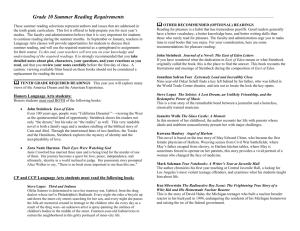

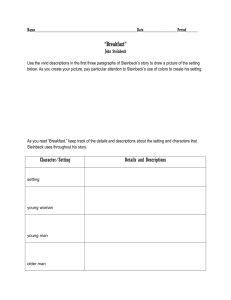

advertisement