Bohuslaen Ships for fertility – Symbols of new Life

advertisement

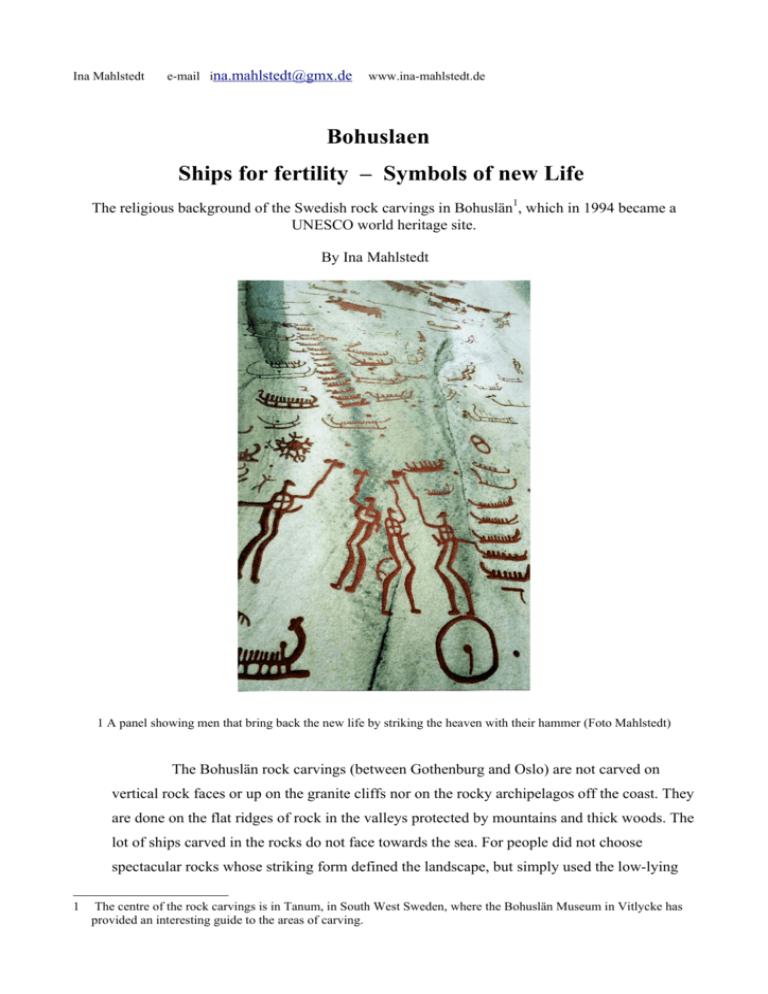

Ina Mahlstedt e-mail ina.mahlstedt@gmx.de www.ina-mahlstedt.de Bohuslaen Ships for fertility – Symbols of new Life The religious background of the Swedish rock carvings in Bohuslän1, which in 1994 became a UNESCO world heritage site. By Ina Mahlstedt 1 A panel showing men that bring back the new life by striking the heaven with their hammer (Foto Mahlstedt) The Bohuslän rock carvings (between Gothenburg and Oslo) are not carved on vertical rock faces or up on the granite cliffs nor on the rocky archipelagos off the coast. They are done on the flat ridges of rock in the valleys protected by mountains and thick woods. The lot of ships carved in the rocks do not face towards the sea. For people did not choose spectacular rocks whose striking form defined the landscape, but simply used the low-lying 1 The centre of the rock carvings is in Tanum, in South West Sweden, where the Bohuslän Museum in Vitlycke has provided an interesting guide to the areas of carving. banks of stone that marked the boundary of their fields. And the engravings are carved, where even today the water leaks out over the old pictures and forms long, dark tongues upon the rocks. Dods and ships seem to be the oldest and most common symbolic drawings. 2 In a tongue of water on a flat rock beside a field you can see two ships and a potencial man. Since tousands of years the water runs still over this picture (Foto Mahlstedt). Why did people carve ships where water seeps over the rocks? It is understandable that for people in Mediterranean, dry countries the fertility of the fields and the cyclical coming and passing away of the vegetation is associated with water. But why should water be of such significance in such a rainy place as Sweden? For ships are connected with water. It is known2 that around 2000 B.C, people began to cultivate cereals in Scandinavia. That means that the early farming hunters returned again to Bohuslän in springtime and worked with the earth as soon as it got smooth and warm again after the long lasting winter period. The short summer vegetation facilitated a settled period of existence for roughly five months. Than they had to move again in the woods to survive by hunting. Partial mobility must still have been the Bronze Age way of life in Scandinavia for a long time. 2 Hygen and Bengtsson 2000. 3 Ships with kernels of life (Vitlyckemuseet Rapp.3 Askum) So why did these people carve ships in the tongues of water on the edges of thier fields? Was the earth not damp enough after the winter snow and ice? Why should they draw ships to indicate water, when not for showing the running water of spring? For the water runs when it is not longer frozen to ice. The ship on the rock carvings of Bohuslän symbolises the seasonal water, the water that runs again in spring, when life comes back! When the hunting farmers arrived in Bohuslän again it was the time of the melting ice, when the earth got smooth and warm to take seed. The ships and later other symbols as well were carved to denote the new life coming with the water that no longer lay in a thick layer of ice on the rocks. Ships or sledges refer to the cyclical movement of coming and passing that follows growth patterns. In this sense the sledge is to ice, what the ship means to water. Together they indicate the whole circle of life, in which death and life belong together. Carving ships in the tongues of water was a ritual way of greeting the new life returning with the melting ice. For the drawings symbolise the mysterious return of life after the dead winter period. People awoke the numbed vitality of the earth with them, which had in winter been frozen to lifeless stone and lain buried under the snow. But in spring, when the warming sun starts to melt the ice again and the water rans over the sacred stones with all their pictures, the period of growth could start. It seems that people tried to help life for its return by ritually carving theses symbols in the lifeless stones. First they only touched the stones using a simple circular motion as a way of awakening life out of its winter dreams. The aim was not to fashion a cup mark, but rather to bring to life Mother Earth again, whose vital force had been frozen to stone in the winter cold. These round cup marks can be found worldwide in a Neolithic context3: they are traces of a ritual activity to the back coming of life in a cyclical world order. 4 Ring or cup marks of varying depth, formed by touching Litslena 124 (Coles 2000, fig. 77) In the cyclical order, life and death are bound so closely together that life always appears as to grow out of death. Death, the time of the lifeless not-being seems to be the origin of life. In cyclical thinking life fades down to death and arises back from death. We modern people have underestimated what existential and religious significance this reality had for pagan, pre-Christian people. For them, death was a creative force. It held a mysterious life force that led to a seasonal resurrection of life. Natural rhythms have no beginning and no end. Life flows forth in constant flux and each year people experienced its mysterious renewal through a state of non-being. This awareness of the creative power of death is reflected in the much later Nordic creation myth of Edda: “They struck Ymir dead. From Ymir’s blood was made all water, from his flesh earth and clay, from his hair the trees, from his bones and teeth mountains and rocks, from his skull was made the heaven, from his brain, which the gods hurled into the air, were made clouds…”4 In this myth the world is formed from the death of the ancestral creators. The deity embodies the creation of the world out of non-being and thereby accounts for the creative process of coming and passing. Just as grains of cereal have to die before emerging as new heads, so the world is formed out of the dead body of a creative being that 3 4 Mahlstedt, 2004, p. 114. Peterich, 1963, p. 16. manifests a mysterious ability to engender new life in death. The two parts day and night, life and death, form a dynamic unity whose antithetical natures condition one another. Each in turn gives rise to the other, just as an inhalation gives rise to an exhalation, which in turn leads to another inhalation. Life and death are experienced as a dynamic process, which reveals itself in two different forms. In this meaning sledge and ship, winter and summer, belong together, as the two aspects of the phenomenon of life. The same is represented in whole circles, which refer to the origin of life. (4) Next to them are half circles and some split into four parts with a cross. These could symbolise the temporal order of the four seasons – or also a first orientation in space, which divides the curve of the horizon into four points of the compass to make sense of the ascending and descending points of the life-giving sun. The circles would in that case stand for an idea of the the origin of being in its whole, containing the cyclical order of life. 5 Circles and half circles divided into quarters bring the aspects of death and life together into a whole, Boglösa 138 (Coles 2000, fig. 50) The cyclical rhythms of the year have always shaped the life of the hunters, too. The Lapps viewed natural stones, Sieidi5, as holy sites where they carried out their sacrifices. In the characteristic stone landscape of northern Sweden, an unhewn rock set upright can have a symbolic meaning found only in the stone itself: it illustrates the lifelessness and rigidity of death, which in the life cycle is filled with creative – with divine – power. And so if, from the age of hunting onwards, the deliberately erected or chosen natural stone already manifested a holy energy, then people were now completely dependent in an existential sense on the cyclical power of creation. For the first farmers the phenomenon of the cyclical return of life out of the frozen winter took on a new religious dimension. This is evident in the rock 5 There is a Sieidi sacrificial stone in the Norsk Museum in Oslo. carvings at Bohuslän. On the picture panels, carved next to one another, are ships covered with marks of worship. Over time their appearance has changed. One can find ships that have been carefully, repeatedly carved, up to four metres long, fine, small, embellished even at this stage with heads and with massive loads, or curved lines just suggesting the form, whose symbolic message was always the same: they represent the return of life. 6 Like a huge fleet ships loaded with ever more kernels of life move over the ridge of rocks by a field in Hornes, Östfold, Norvigian (Foto Mahlstedt) Almost all of the ships have small lines drawn inside them, but these can hardly be understood to represent a crew. According to their symbolic message the ships could only have been loaded with what the water brings: namely new life. When the water ran over the picture panels, then new life unfolded. We could talk about something like kernels of life being brought in on the ships. And so something that originally only the cult of touching could awaken could now be seen in a new form, as holy cargo on the ships. The kernels of life may well have been thought of as little beings that came back to life in spring. The mythical world of the hunters had of course always been animated by beings interwoven with all living things.6 The fairies and elves of Scandinavian legend testify to such ideas. Although their original meaning has changed in the context of Christian7 beliefs, they still embody the mysterious, invisible workings of nature. It could even be the case that the fairies and elves were set against the goblins and trolls, destructive forces who transformed life into the death deemed necessary for renewal and return in the old, cyclical 6 7 I am thinking, for example, of the Kami of the Japanese Shinto Religion. Here meaning above all apocalyptic and monotheistic beliefs. order of things. In the history of religion, it is a known fact that abstract phenomena are manifested in the form of essential phenotypes. This is necessary as a way of making the creative powers of life into something tangible and understandable. The more clearly these powers are explained in mythical imagery, the more powerful and effective they are in establishing order for the people. 7 Huge ships loaded with kernels of life (Vitlyckemusest. Rap. 5Tanum 326) It is possible that the ritual of carving was thought to release the sleeping kernels of life from out of the stone. Some ships are carved very deep into the stone, from which it can be assumed that the grooves continued to be deepened for years on end afterwards so as to gain potent creative force from the old images. Over time, the hope of new, strong food growing on the fields was borne on bigger and bigger ships arriving packed with kernels of life. Sometimes small figures or even circles or animals appear between the lines, which towards the end of the tradition are often portrayed as fertile men. Thus they personify a masculine potency fertilising the female earth. And so the heavily laden ships come along, prows adorned, carrying figures whose hands appear to finish in twigs and leaves. Like the trees, they point towards the re-emergence of the vegetation. life from out of the stone. Some ships are carved very deep into the stone, from which it can be assumed that the grooves continued to be deepened for years on end afterwards so as to gain potent creative force from the old images. Over time, the hope of new, strong food growing on the fields was borne on bigger and bigger ships arriving packed with kernels of life. Sometimes small figures or even circles or animals appear between the lines, which towards the end of the tradition are often portrayed as fertile men. Thus they personify a masculine potency fertilising the female earth. And so the heavily laden ships come along, prows adorned, carrying figures whose hands appear to finish in twigs and leaves. Like the trees, they point towards the re-emergence of the vegetation. 8 Lökeberg, trees. Circles (Coles 1990, fig. 69) However, we cannot assume that the pictures were carved as a plea to the gods for rich harvests, as was later the case with the Vikings, whose gods had become powerful rulers of the heavens. As yet, in mythological frameworks of understanding, there existed no powers outside creation that could be called upon. It was life itself that was holy. It came and went again in a seasonal rhythm, and in this sense it was seemingly of fundamental importance to assist its return from death, to accompany it with ritual so that it could return strong and luxuriant to the fields. 9 Hieros Gamos on the panel at Vitlycke (Coles, 1990, fig. 108) and from the panel at Askum Raä (Vitlyckemuseet Rap.3) The symbolism of the rock carvings referred to the fields and the life-giving force of Mother Earth. The only explanation for the fact that hardly any women are to be found on the Bohuslän rock carvings is that the images were intended to refer absolutely to the female earth. Later the picture of a Hieros Gamos, the holy wedding, was carved, where the symbol of man and woman illustrates the fruitful act of creation between heaven and earth The farming year will have begun with the awakening of new life, whereby sledge ships, animals or circles were carved to animate the kernels of life again. People knew that the fertility of the fields would be assured if they awoke the life force frozen into the stone by tapping out a cup mark or with the ritual gesture of carving and re-carving old symbolic images. The image of the hammer-wielding creative beings with their mighty penises represented the restoration of a mythical event of creation, which had brought about the return of life. In the late Bronze Age milieu, methods of cultivation slowly developed to the point where a permanent settled existence became possible, and this in turn no doubt gave rise to feelings of envy and struggles for possession, for cultivated fields, dwellings and wealth. The world is now a place of war, violence and greed, of cunning and unpredictability. Violent male strength becomes an ideal that also finds expression in religious and mythical ideas. Nordic myths reflect this tendency, creating divinities filled with strength, power, pugnacity and vindictiveness. We find a very late written version of these in the Icelandic prose Edda, already coloured with a Christian image of high divinity. Nonetheless, the ancient symbolism of the rock carvings is still recognisable in the attributes of the gods: 10 Creative being with life-giving hammer. Backa, Aspeberget and Vitlycke (Coles, 1990) We meet Odin, the strong ruler, assigned power over life and death with his spear and the ring as the symbol of origin. We see the god of thunder, Thor, with a hammer and his boar, bristles glistening like the sun, and the god of fertility Frey, to whom the ship is assigned.8 The Icelandic poet Snorri (1179-1241) can give no reason or explanation for any of the divine attributes. However, just as in the symbolism of rock carvings an explanation for the ship as a symbol of fertility can be found in the running water, no longer frozen to ice, so the symbol of the hammer swung by the great god Thor can be understood in the myths of the “stony heaven”. H. Reichelt,9 who studied this Nordic myth complex as early as 1913, discovered that during the Indo-Germanic journeys, the myth travelled from northern Europe over Persia and as far as India. Briefly, the myth is as follows:“In early times the stony heaven became a god alongside the goddess Earth…In the beginning darkness reigned. Then was born a hero, son of the stony heaven and the earth, huge of stature, who smote the heaven to pieces with a 8 9 R.I.Page 1963, p. 97. H.Reichelt 1913. stone hammer and paved the way for light and rain to reach the earth.”10 The stony heaven can be understood as a symbolic image for the cyclical winter death, which creates life again in spring.11 For his return the myth had a wonderful, simple explanation: the stony heaven is smashed open with divine power, and life, that is, light and rain, comes forth again. And the instrument of liberation – a sharp, pointed object – axe, hatchet, cleaver, hammer – becomes the symbol of return. It is interesting that the axe, the hammer and the hatchet have been found in almost all Neolithic cultures of the world and in countless graves.12 Often they lay next to or on top of the dead person’s heart. We can presume that the dead were supposed to use them to break through the rigidity of death (the “stony heaven”), and return to the cycle of life. In the hand of powerful rulers and religious protagonists, the hammer, the staff and the axe symbolised their power over life and death. 11 Circle men with penis and hammer – and penis men from Coles p. 75 Lasse Bengtsson13 of the Vittlycke museum in Bohuslän excavated large quantities of burned, shattered stones from the foot of the panels of rock carvings. These could provide a clue to annual ritual celebrations, during which stones were broken open with the help of fire, symbolically shattering the “stony heaven” in order to free life from its frozen winter state. But also the carved, pointed stones that lay between the burnt pebbles could have been interpreted as holy tools, used in the drawings of these symbolic images to “open” the stone again each year and to summon the kernels of life to vigorous new growth in the fields. 10 H.Reichelt 1913, p. 27. 11 Mahlstedt 2004, p. 65. In Zoroastrism the creator god Ahura Mazda forms his creation sitting in a Stony Heaven, initially in a spiritual, invisible menog form before it becomes visible, after 3000 years (originally 3 months), in its getig form. 12 Mahlstedt 2004, p. 96. 13 A.S.Hygen and L.Berngtsson In the mythical framework of the “stony heaven”, male figures with their axes lifted in readiness for the blow, set between older ships and over the worshipping traces of the cup marks, embody the powerful fertility with which the spring rain poured into the furrows of Mother Earth, giving her renewed life and fertility. The virile power of the gods was represented by an oversized penis, often jutting out comically from between the thighs. Masculine potency is indicated by way of a spear or hammer, whether it be the great gods or the many small men between the ships or the roughly drawn powerful male thighs. The rock carvings are nearly always of men, because male fertility was needed to fertilise Mother Earth in spring. . 12 Chariots with wheels as symbol of origin at Hjälpesten (Coles 1990 fig. 52) and Askum (Vitlyckemuseet Rapp. 3). The order of life, in other words the rhythm of the seasons that dictates the cyclical coming and passing of things on the earth, is determined by the sun. Today that is an uninteresting fact, but for the Neolithic people it was a religious realisation. It linked the origin of life to the order created by the sun, the cause of day and night, summer and winter and thus death and life. In Nordic myth, the sun is represented as a force travelling across the heavens in a chariot with wheels displaying the symbol of origin. The symbol of the chariot makes apparent the connection between the seasonal movement of the sun and the cyclical process of renewal, which determined early farming life. Many rock carvings show circular forms that can eventually come to have legs, heads and arms and to swing a lifted hammer. These are not images of a divine embodiment of the sun, but rather symbolic representations of the origin of life and of the order of things. Not until the late Bronze Age era, when the tendency for immortal divinities becomes established – as opposed to religious ideas that follow a cyclical pattern of death and return – the creative power is personified in the mighty gods as we know from Nordic mythology. Here, the weather god Thor swings his hammer or Odin his spear as a sign of his power over life and death. The Vikings, who a thousand years later no longer carved rock paintings, imagined the ancient symbol of life, the sun, as a creative and ordering power being pulled across the heavens by horses in a fiery chariot. 13 Creative beings with powerful penis, circle men and sledge ships full of essential kernels of life. Symbols of the return of life after the deathly rigidity of winter (Vitlykemuseet Rap. 3) Nonetheless, they did still place ships, sledges and chariots into the graves of their leaders. This can hardly have been to guarantee them an entertaining existence on the other side; no doubt it was so that they could be accompanied to the other side by the ancient symbols of the pagan order, which enabled the return to life. Elaborate sledges, chariots and ships, such as those on show as part of the exhibition of the Oseberg grave in Oslo14, still point to the symbolism of cyclical natural order. This was the belief system of pre-Christian paganism, which recognised the creative powers leading to the annual emergence of new life in symbols of ships, cup marks, circles or chariots and most potential men. Bibliography Coles, John and L. Bengtsson (1990) Bilder vergangener Zeiten, Uddevalla Coles, John (2000) Pattens in a Rocky Land, Rock Carvings in South-West Uppland Christensen, A.E. (1987) Führer durch das Wikinger Museum, Oslo Sweden, Uppsal, Aun 27 Hygen, A.-S. and L. Bengtsson (2000) Felsbilder im Grenzbereich, Sävedalen Mahlstedt, Ina (2004) Die religiöse Welt der Jungsteinzeit, Darmstadt Pager,R. I. (1993) Nordische Mythen, Stuttgart Peterich, Eckart (1963) Götter und Helden der Germanen, München Reichelt, H. (1913) Der steinerne Himmel in Indogermanische Forschungen 32 Arkeologist rapport 3 fränVitlyckemuseet, Askum 14 Universitetets Oldsaksamling 1987 Oseberg finds in the Viking museum in Oslo.