Animals are Part of the Working Class Reviewed

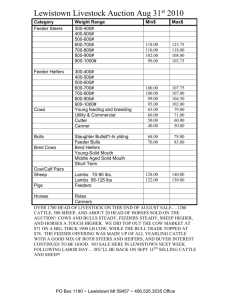

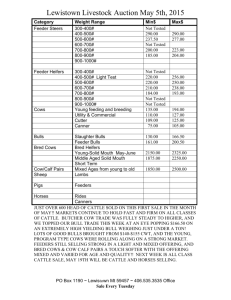

advertisement