set the oppressed free!

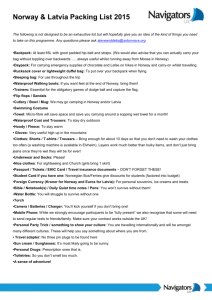

advertisement