Predictors of protest, conventional and civic participation: A

advertisement

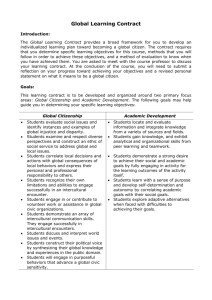

Predictors of protest, conventional and civic participation: A representative study of Slovenian youth Assistant Prof. Dr. Andrej Kirbiš Department of Sociology, Faculty of Arts, University of Maribor, Slovenia andrej.kirbis@um.si Assistant Prof. Dr. Marina Tavčar Krajnc Department of Sociology, Faculty of Arts, University of Maribor, Slovenia marina.tavcar@um.si Assistant Tina Cupar Department of Sociology, Faculty of Arts, University of Maribor, Slovenia tina.cupar@um.si Abstract: Previous studies have indicated that protest participation (i.e. elite-challenging behaviour) has been increasing in recent decades in industrialized and postcommunist countries, along with the emergence of a “critical citizen” (Norris, 1999; Inglehart and Catterberg, 2002; Dalton and van Sickle, 2005; Inglehart and Welzel, 2007; Kirbiš, 2013). In addition, past research has also indicated that protest engagement is more frequent among more pro-democratic oriented public (both in established and postcommunist European democracies; Kirbiš, 2013) and among youth; yet young people are on the other hand also less frequently active in conventional (i.e. “political party”) politics (Kirbiš and Flere, 2011). Few studies have compared predictors of different dimensions of citizen participation among postcommunist youth. The purpose of the present study was to examine Civic Voluntarism Model (CVM; Verba et al., 1995) by testing three competing models (resources, political cultural and social network model) and their power in predicting different dimensions of citizen participation. We analyzed survey data from Youth 2010 study – a representative sample of Slovenian youth (N = 1257, M age = 22.5 years, SD = 4.25; 48.8 % female). Principal component analysis of indicators of citizen participation identified three distinct dimensions of citizen participation: conventional political participation, protest participation and civic (social) participation. Results of regression analyses indicated that the three models within CVM explained 17.2 % of variance (Adjusted R2) in protest, 13.0 % in conventional and 5.8 % of variance in civic participation. Political cultural model explained the largest amount of variance in all three participation dimensions. Among predictor variables, political interest, a feeling of duty to vote, more frequent discussion of politics with friends/peers, female gender and older age were the strongest and most frequently significant predictors of citizen participation. Implications of the results are discussed in terms of the future of democratic consolidation processes in postcommunist states. Keywords: citizen participation, protest participation, conventional political participation, youth, democratic consolidation, postcommunist democracies, Slvoenia. 1.1 Introduction Citizen participation – in a broader sense defined as activities of individuals or groups with the aim to influence the life of the political community (Macedo et al., 2005; Zukin et al., 2006), and in a narrow sense defined as activities whose purpose or consequence is influencing decision-making (Kaase and Marsh, 1979; Parry et al., 1992) – is considered one of the key elements of a functioning democracy (Almond and Verba, 1963; Pateman, 1970; Dahl, 1972; Barber, 1984; Parry and Moyser, 1994). Verba and Nie (1972: 1), for instance, argued that “Where few take part in decisions there is little democracy; the more participation there is in decisions, the more democracy there is”. Within the context of studies on citizen participation, participation of youth and young adults in old and new (postcommunist) democracies has received increasing attention during the last decades. One of the important aspects of citizen participation is also participation inequalities; i.e., what is the extent of differences in citizen participation among different groups within societies and what accounts for (explains) these differences. Our analysis will involve three dimensions of citizen participation since researchers most commonly differentiate between conventional political participation (e.g., trying to convince others who to vote for, contacting politicians, contributing money to or working for political parties/candidates, etc.), protest participation (e.g., demonstrating, boycotting products, signing petitions, etc.) and civic/social participation (e.g., being a member of a voluntary organization, doing charitable work, etc.) (Barnes et al., 1979; Mihailović, 1986; Pantić, 1988; Inglehart and Catterberg, 2002; Torney-Purta and Richardson, 2002; Zukin et al., 2006). Previous studies have indicated that among these dimensions, protest participation (i.e. “elitechallenging” behaviour) has been increasing in recent decades in industrialized and postcommunist countries and that a phenomenon of “critical citizen” emerged alongside (Norris, 1999; Inglehart and Catterberg, 2002; Dalton and van Sickle, 2005; Inglehart and Welzel, 2007; Kirbiš, 2013). In addition, past research has also indicated that protest participation is more frequent among more pro-democratic oriented public (both in established and postcommunist European democracies; Kirbiš, 2013) and among youth; yet young people are on the other hand also less frequently active in conventional (i.e. party) politics (Kirbiš and Flere, 2011). Few previous studies have compared predictors of different dimensions of citizen participation among postcommunist youth. One of the most prominent explanations of within-country differences in citizen participation has been the Civic Voluntarism Model (CVM; Verba et al., 1995), which “entails the accumulation of various factors—resources, location in networks of recruitment, and psychological involvement in politics—that facilitate participation” (Burns et al., 2001: 198). In other words, the question on factors of political participation (i.e., the question of “Why people participate?”) can be inverted and a question may be asked: why people do not participate (Verba et al., 1995: 269). Verba and colleagues argue that people are politically inactive because they can’t be, don’t want to be or because nobody asked them to be politically active (ibid.: 269). In the following paragraphs we turn briefly to each of these three factors influencing participation: resources, engagement and recruitment/mobilization. Resource model has been one of the most widely accepted models of citizen participation (Norris, 2002: 29). The argument goes that personal resources, especially those regarding one’s socioeconomic status (SES), may increase the likelihood of one’s engagement in politics and public life. Specifically, “SES increases citizens’ skills with regard to managing and understanding political content and being active in the public sphere. Individuals with higher SES therefore have more resources available (higher education and occupational status, more economic resources, etc.), which allows them to participate in political life more frequently and with less effort” (Kirbiš, 2013: 182; see Cho et al., 2006; Sandell Pacheco and Plutzer, 2008). In fact, Verba and colleagues argue that the majority of differences in participation at the individual level stem from the socioeconomic status of an individual (Verba et al., 2003: 56). Other resources, which include time, money (e.g., income, as an important dimension of SES), and civic (verbal and cognitive) skills (Burns et al., 2001: 201; Badescu and Neller, 2007) may also impact citizen participation. Political cultural model or psychological involvement/engagement model is the second group of factors previously found to influence citizen participation within the CVM. The concept of psychological political engagement refers to the motivational and cognitive elements of political culture (Norris, 2002; Pantić in Pavlović, 2009), which in past research proved to be one of the most important factors of citizen participation. In other words, being motivated to be active in politics, being interested in political life, and not feeling powerless when it comes to influencing political institutions and political actors, increases the likelihood of citizen participation. Within political engagement model, political interest (Macaluso and Wanat, 1979; Shin, 1999: 117; Patterson, 2005; Hutcheson and Korosteleva, 2006), political trust (Thomassen and van Deth, 1998; Letki, 2004; Hadjar and Beck, 2010; cf. Spehr and Dutt, 2004; Besley, 2006; Smith, 2009), internal political efficacy (Solhaug, 2006; McIntosh et al., 2007; cf. DiFranceisco in Gitelman, 1984; Bäck in Teorell, 2005) and external political efficacy (Thomassen and van Deth, 1998: 158; Roller and Rudi, 2008; 266; van Deth, 2008: 203; cf. Duch, 1998) were found to impact citizen participation. Within political cultural model, other concepts such as (dis)satisfaction with democracy (Badescu and Neller, 2007), having a sense of duty to be active in politics (e.g., to turn out to vote) and others also play a prominent role (Norris, 2002: 29). Finally, social networks and recruitment, including within different settings of institutional affiliation, can also greatly impact one’s citizen participation. As Burns and colleagues show, institutional involvement (e.g., being employed, being a member of a voluntary association, being engaged in a religious institution) has been found linked to citizen participation (Burns et al., 2001: 198; see, among others, Verba et al., 1995; Conway, 2000; Norris, 2002). When examining the impact of social networks on citizen participation, it is necessary to include not only nominal institutional affiliation, but also a wider social context, i.e. family and friends/peer context, (news) media exposure, religious engagement, etc. For this reason our analysis will include three dimensions of social network: 1) political media use, which was previously found to be associated with higher levels of citizen participation (Pasek et al., 2006, Romer et al., 2009); 2) individual’s social networks with regard to political discussions both with family members and friends/peers (discussing politics with parents and peers) since discussing politics more frequently has previously also been found to be associated with more frequent citizen participation (McLeod et al., 1999; Scheufele, 2002; Kang and Kwak, 2003; also see Bimber et al., 2014); and 3) church attendance as an indicator of not merely institutional affiliations but also active engagement in religious life, which has previously also been found to increase the likelihood of citizen participation (Shupe, 1977; Brady et al., 1995; Leong, 2004; Conklin, 2008; Smith, 2009). 1.2 The aim of the study The aim of the present study was to examine the predictors of three dimensions of citizen participation; specifically, to test the predictive power of Civic Voluntarism Model, and within it, to compare the predictive power of each of the three individual predictive models of citizen participation using data from a representative national study of Slovenian youth from 2010 (young people aged 15–29 years). The main research question was: which of the three citizen participation dimensions are explained to the largest extent by CVM (RQ1). The second research question was: is there a model which explains the largest amount of variance in all three citizen participation dimensions (RQ2)? The third research question was: which individual variable is the best predictor of citizen participation (RQ3)? Finally, based on previous studies we predicted that each of the three models would significantly predict each of the dimensions of citizen participation (Hypothesis 1). 1.3 Methods 1.3.1 Sample Slovenian Youth 2010 study was based on a representative random sample of Slovenian youth. The target population were all residents residing in the Republic of Slovenia, who were on July 26th aged between 15 and 29 years (N = 1257; Mage = 22.90; SD = 4.25; 48.3 % women). Field survey was conducted between July 27th and September 24th in the form of face-to-face interviews. The target population of the study was prior stratified into twelve statistical regions and six types of settlements (for details on sampling, data collection, etc., see Lavrič et al., 2011). The survey questionnaire consisted of two parts: oral and written part. The oral part of the questionnaire was conducted within face-to-face interviews with interviewers reading the questions aloud to interviewees and with interviewers filling out survey responses they received from the respondents. Upon completion of the oral part of the questionnaire the interviewer handed the respondent the written questionnaire and asked him/her to fill out the written questionnaire himself. Written part of the questionnaire consisted of questions that were more personal and intimate in nature. 1.3.2 Measures 1.3.2.1 Predictor variables Resources model We measured respondent’s family and personal socioeconomic resources by means of three commonly used indicators of socioeconomic status (SES): maternal and paternal educational level and self-perceived family material status of respondents. Parental education We measured father’s and mother’s educations with two identical questions on a 9-point scale: “What is the highest achieved level of [your father’s / your mother’s] education?” (1 = uncompleted primary school; 2 = completed primary education; 3 = uncompleted vocational or other secondary education; 4 = completed 2-year, 2.5-year or 3-year vocational secondary education; 5 = completed 4-year secondary education; 6 = uncompleted higher non-university education; 7 = completed 2-year higher non-university education; 8 = completed university education; 9 = completed master or doctorate degree). For the purposes of statistical analyses the values were recoded into a 3-point scale: 1 = uncompleted secondary education (original values 1, 2, 3); 2 = completed secondary education (original values 4, 5, 6); 3 = completed tertiary education (original values 7, 8, 9)). Self-perceived family material status Respondents also assessed their family material (economic) status in comparison to perceived Slovenian average with the following question: “How do you rate the material situation of your family according to the Slovenian average”? Family material status was coded on a 5point scale (1 = highly below average; 5 = highly above average). We recoded the 5-point scale into a 3-point scale of family’s relative material status (1 = (highly) below average, 2 = average; 3 = (highly) above average). Three demographic variables included in our resources model were age (measured as year of birth, recoded into age in years and the into age groups: 1 = 15-18 years, 2 = 19-24 years, 3 = 25-29 years), gender (female = 1, male = 2) and size of current residential settlement (1 = larger city, 2 = small town (between 1,000 and 50,000 inhabitants), 3 = countryside/village). All three demographic variables were included in resources model since previous studies have indicated that age (Zukin et al., 2006; Quintelier, 2007; Dalton, 2008; Fahmy, 2006), gender (Almond and Verba, 1963; Parry et al., 1992; Rosenstone and Hansen, 1993; Schlozman et al., 1995; Verba et al. 1995; Vassallo, 2006) and living in urban environment (Milbrath, 1965: 114; Mihailović, 1986; Inglehart, 1997; Shin, 1999: 113) were significant predictors of more frequent citizen participation, although previous studies of Slovenian youth (e.g., Kirbiš and Flere, 2011; Kirbiš and Zagorc, 2014) have not detected significant differences in citizen participation between age groups and between genders. Political cultural model The predictors included in this model were political interest, ideological (left-right) orientation, internal and external political efficacy, satisfaction with the state of democracy in Slovenia, and attitude that turning out to vote is a citizen’s duty. Interest in politics was measured with the following item: “People have different interest in politics. How interested would you say you are in politics? (1 = not interested at all; 4 = very interested). Ideological (left-right) orientation was tapped with the following item: “In politics people talk about “left” and “right”. Where would you place yourself on a scale from 0 to 10, where “0” indicates “left”, “10” indicates “right” and where “5” indicates “the middle”? Please assess using the scale below”. Internal political efficacy was a tapped with the flowing item: “I have a good understanding of politics”. The indicator was rated on a 5-point Liker scale (1 = does not apply to me at all; 5 = applies completely to me). External political efficacy was a summation scale which consisted of three indicators: “Politicians are generally interested only in getting elected and not in what voters really want”; “People like me don’t have any influence anyway on what the authorities do” and “I don't believe politicians spend a lot of time on what people like me think”. The indicators were rated on a 5-point Liker scale (1 = does not apply to me at all; 5 = applies completely to me). Reliability of the scale was found to be sufficiently high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76). Satisfaction with the state of democracy in Slovenia was measured with the following item: ”In general, how satisfied are you with the state of democracy in Slovenia? Please indicate it on a scale from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 5 (very satisfied), and where “3” indicates the middle point. Please assess using the scale below”. Finally, we measured the extent of (dis)agreement that turning out to vote is citizens’ duty with the following item: “It is every citizen’s duty to take part in elections” (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree). Social network model Predictors included in this model were the use of different forms of media with political contents, discussing politics with parents and with friends/peers, and the frequency of church attendance. Political media use was measured with the following questions: How often do you follow politics/news in the following mass media: A) TV; B) newspapers; C) radio; D) the Internet (1 = never, 2 = less than once a month, 3 = 1-3 times a month, 4 = 1-3 times a week, 5 = 4-6 times a week, 6 = daily). Summation scale was formed from these five items and the reliability of the scale was found to be sufficiently high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81). Political discussion was measured with the following two items: How often do you discuss politics with: A) parents; B) friends/peers (1 = never, 2 = less than once a month, 3 = 1-3 times a month, 4 = 1-3 times a week, 5 = 4-6 times a week, 6 = daily). Church attendance was measured with the following question: “How often do you attend church/religious services?” (1 = regularly, several times a week; 2 = regularly, every week; 3 = at least one or twice a month; 4 = several times a years; 5 = one of twice a year for religious holidays; 6 = never). The original values were then recoded into five values (1 = never; 2 = one of twice a year for religious holidays; 3 = several times a years; 4 = at least one or twice a month; 5 = regularly, at least weekly). 1.3.2.2 Outcome variables Youth 2010 survey questionnaire contained numerous indicators of citizen participation. Principal component analysis (PCA) carried out on thirteen indicators of citizen participation identified three distinct dimensions of citizen participation: non-electoral conventional political participation, protest participation and civic (social) participation (PCA results not shown; analyses can be obtained from the authors). In the next paragraphs, we describe the indicators and summations scales of participation dimensions. Non-electoral conventional political participation Non-electoral conventional political participation was measured with five items. The following question was asked for all participation items: “People are active in politics in different ways. Have you ever been engaged in the following activities or would you be engaged in them if you had the possibility?”. The items were: “Try to convince others to vote for the same candidate or party as me”, “Contact politicians”, “Contribute money to a political party”, “Work for political party or candidate”, and “Hand out leaflets with political content”. All items were rated on a scale from 1 to 3 (1 = would definitely not do; 2 = would probably do, 3 = have already done). Summation scale was formed and the reliability of the scale was found to be sufficiently high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.70). Protest participation Protest participation was tapped with following four items: [Have you ever] “Sign a petition (printed or electronic)”, “Attend lawful demonstrations”, “Boycott buying certain products for political, ethical or environmental reasons”, “Buy certain products for political, ethical or environmental reasons”. All items were rated on a scale from 1 to 3 (1 = would definitely not do; 2 = would probably do, 3 = have already done). Summation scale was formed and the reliability of the scale was found to be sufficiently high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.65). Civic participation Civic participation was measured with four items on the frequency of: “Helping peers with learning”, “Counseling peers on their problems”, “Helping the elderly”, “Helping physically/mentally challenged”. All items were rated on a scale from 1 to 3 (1 = would definitely not do; 2 = would probably do, 3 = have already done). Summation scale was formed and the reliability of the scale was found to be sufficiently high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73). All three outcome summation scales were split into quartiles, which means that each respondent received a value from 1 (lowest quartile on a particular summation scale) to 4 (highest quartile on a particular summation scale). 1.4 Results In accordance with our main study aim we were first interested in how much of the variance in three dimensions of citizen participation could be explained by three competing explanatory models. Multiple regression analysis was employed; Table 1 presents the results. Table 1: Hierarchical regression analyses estimating the effects of resources model, political cultural model and social network model on three dimensions of citizen participation: conventional political participation (CPP), protest participation (PP) and civic participation (CP) among Slovenian youth in 2010. Convention. P. B Constant 1.51 .35 Gender (male) .04 .05 Age group .14 .04 Size of settlement Father’s education Mother’s education Subjective SES Political interest Ideological (L-R) placement Internal inefficacy External inefficacy Satisfaction with democracy Voting is duty Political media use Political discussions with parents Political discussions with peers Church attendance SE B β B Constant 1.21 .31 .02 Gender (male) -.11 .05 -.07 .13 Age group .10 .03 .10 -.04 .04 -.04 -.01 .02 -.01 .01 .02 .01 .03 .06 .02 .09 .04 .10 -.01 .01 -.01 -.07 .04 -.08 -.01 .03 -.01 .00 .03 .00 -.03 .02 -.03 .04 .02 .06 .07 .03 .10 .07 .03 .09 -.01 .02 -.01 Size of settlement Father’s education Mother’s education Subjective SES Political interest Ideological (L-R) placement Internal inefficacy External inefficacy Satisfaction with democracy Voting is duty Political media use Political discussions with parents Political discussions with peers Church attendance SE B β Protest P. -.09 .03 -.09 .02 .02 .05 .01 .02 .02 .07 .05 .04 .08 .04 .10 -.01 .01 -.03 -.02 .03 -.02 .03 .03 .03 .02 .03 .03 .05 .02 .08 .01 .02 .02 .07 .03 .10 .11 .03 .17 -.01 .02 -.02 B Constant 1.91 .35 Gender (male) -.21 .05 -.13 .02 .04 .02 .01 .04 .01 .01 .02 .02 .02 .02 .05 -.08 .06 -.05 -.10 .04 -.11 -.01 .01 -.02 -.06 .04 -.08 .09 .03 .10 .01 .03 .01 .09 .02 .13 .03 .02 .04 .01 .03 .01 .00 .03 .00 .07 .02 .10 Age group Size of settlement Father’s education Mother’s education Subjective SES Political interest Ideological (L-R) placement Internal inefficacy External inefficacy Satisfaction with democracy Voting is duty Political media use Political discussions with parents Political discussions with peers Church attendance R2 = .13 R2 = .172 R2 = .058 F = 10.09 F = 13.69 F = 4.75 SE B β Civic P. Source: Slovenian Youth 2010 Study (2011). Note: Beta values that are underlined indicate p < .05; beta values that are in bold indicate p <. 01; and beta values that are both underlined and in bold indicate p < .001. Table contains only values from model 3, where all three predictor models were entered into regression analysis. Remaining data can be obtained by interested reader by contacting the authors. R2 = Adjusted variance. In all three models, resources variables together with three demographic variables (gender, age group and size of residential settlement) were entered at Step 1. These variables explained combined 4.0 % of the adjusted variance in conventional political participation. After the entry of six variables of political cultural (psychological political involvement/engagement) model at Step 2, the total variance explained by the model as a whole was 10.8 %, F (12, 963) = 10.81, p < .001. Six political cultural variables explained an additional 7.3 % of the variance in conventional political participation, after controlling for resources variables (F change p < .001). Finally, three social network variables were entered into the model explaining an additional 2.5 % of the variance in conventional political participation, after controlling for resources and political cultural variables. Final model explained 13 % of variance (adjusted) in conventional political participation. In the final model, only four variables were statistically significant predictors of more frequent conventional participation: higher age (beta = .13, p < .001), more frequent discussions of politics with parents (beta = .10, p < .05), higher political interest (beta = .10, p < .05) and more frequent discussions of politics with friends/peers (beta = .09, p < .05). With regard to protest participation, resources variables together with three demographic variables were again entered at Step 1. These variables explained combined 6.4 % of the adjusted variance in protest participation. After the entry of six variables of political cultural model at Step 2, the total variance explained by the model as a whole was 13.4 %, F (12, 963) = 13.58, p < .001. Six political cultural variables explained an additional 7.5 % of the variance in protest participation, after controlling for resources variables (F change p < .001). Finally, three social network variables were entered into the model explaining an additional 4.1 % of the variance in protest participation, after controlling for resources and political cultural variables. Final model explained 17.2 % of variance (adjusted) in protest participation. In the final model, six variables were statistically significant predictors of more frequent protest participation: those discussing politics more frequently with their friends/peers (beta = .17, p < .001), older youth (beta = .10, p < .001), those more interested in politics (beta = .10, p < .05), those living in urban environment (beta = .09, p < .01), those saying that voting is a duty (beta = .08, p < .05) and women (beta = .07, p < .05) were significantly more frequently engaged in protest activities. With regard to civic participation, resources variables together with three demographic variables were again entered at Step 1. These variables explained combined 2.4 % of the adjusted variance in civic participation. After the entry of six variables of political cultural model at Step 2, the total variance explained by the model as a whole was 5.2 %, F (12, 961) = 5.42, p < .001. Six political cultural variables explained an additional 3.4 % of the variance in civic participation, after controlling for resources variables (F change p < .001). Finally, three social network variables were entered into the model explaining an additional 1.0 % of the variance in civic participation, after controlling for resources and political cultural variables. Final model explained 5.8 % of variance (adjusted) in civic participation. In the final model, five variables were statistically significant predictors of more frequent civic participation: those saying that voting is a duty (beta = .13, p < .001), women (beta = .13, p < .001), those less interested in politics (beta = -.11, p < .05), those with more frequent church attendance (beta = .10, p < .01) and those reporting lower levels of external political efficacy (beta = .10, p < .01) were significantly more frequently engaged in civic activities. With regard to our main research question RQ1 (Which of the three citizen participation dimensions is explained to the largest extent by CVM?) the results indicated that CVM is the best explanatory model for protest participation (Adj. R2 = 17.2 %), followed by conventional political participation (Adj. R2 = 13 %) and civic participation (Adj. R2 = 5.8 %). With regard to the second research question (Is there a model which explains the largest amount of variance in all three citizen participation dimensions?) we found that political cultural (psychological engagement) model contributed to the largest R2 change in all three dimension of citizen participation: 7.3 % in conventional political participation, 7.5 % in protest participation and 3.4 % in civic participation. Other two models predicted substantially smaller amounts of variance. With regard to the third research question (Which individual variable is the best predictor of citizen participation?) the results indicated that the only predictor variable that was significant in all three citizen participation dimensions was political interest. Interestingly, higher levels of political interest were (consistent with results of previous studies; e.g., Verba et al., 1995: 352; Burns et al., 2001: 267; Martin and van Deth, 2007; Bimber et al., 2014; also see Conway, 2000) found to predict more frequent conventional and protest participation, yet inconsistent with previous studies (Badescu and Neller, 2007; Martin and van Deth, 2007) less frequent civic participation. The second best predictor within political cultural model of citizen participation was the sense of duty to vote, which significantly and positively impacted both conventional and protest participation. Within social networks model discussing politics with friend/peers was significantly and positively associated with two participation dimensions: conventional and protest participation, followed by discussing politics with parents (associated with more frequent conventional participation), and church attendance (associated with more frequent civic participation). Finally, based on previous studies we predicted that each of the three models would significantly predict each of the dimensions of citizen participation (Hypothesis 1). Our H1 was confirmed since each three models contributed to significant (.05< p <.001) R2 change in all three dimensions of citizen participation. 1.5 Discussion and conclusion The present study examined the predictors of three dimensions of citizen participation by testing the predictive power of Civic Voluntarism Model and by comparing the predictive power of each of the three individual predictive models of citizen participation within CVM. Nationally representative data from the study of Slovenian youth from 2010 (young people aged 15–29 years) was employed. Although Civic Voluntarism Model was found to significantly predict all three dimensions of citizen participation, it was also found that it was not a substantial predictor, since it predicted only from 17.2 % of adjusted variance in protest participation to 5.8 % of adjusted variance in civic participation. It seems that among Slovenian youth CVM is able to predict almost a fifth of protest participation but less than 6 % of civic participation. Within CVM, political cultural model was the best predictor explaining the largest amount of variance in all three dimensions of citizen participation. Specifically, political interest was the only significant predictor in all three dimensions of participation, with those being more interested in politics also being more conventionally politically active (consistent with other studies; e.g., Verba et al., 1995: 352) and more protest engaged, while, at the same time, being less civically engaged. This latter finding is in contrast with other studies on the link between political interest and civic participation (e.g., associational involvement; see Badescu and Neller, 2007). Future studies should take a deeper look at the reasons for such a link among Slovenian youth. As already mentioned, the second best predictor of citizen participation within political cultural model was the sense of duty to vote, which significantly and positively impacted conventional and protest participation, but not civic participation. It is especially interesting that a sense of duty to vote predicts protest participation, after controlling for all other variables, which is a finding in need of deeper inspection in the future. Within social networks model discussing politics with friend/peers was found to be significantly and positively associated with conventional and protest participation, discussing politics was found to be significantly and positively associated with more frequent conventional participation, and church attendance was found to be significantly and positively associated civic participation. All other social networks predictors proved not to be significant. It seems that discussing politics with friends/peers is the most important factor influencing citizen participation of Slovenian youth, even when controlling for all other variables in the model. Our study results thus indicate that future studies should more closely examine political socialization processes, especially those taking place in school, peer group and family. Interestingly, in our study political media use was found insignificant predictor of all three participation dimensions. Finally, within resources model none of the indicators of socioeconomic status proved a significant predictor in either dimension of citizen participation. In other words, we detected no socioeconomic inequalities in citizen participation among Slovenian youth using our three indicators of SES. Although this seems encouraging for the process of democratic consolidation, two points should be emphasized. First, an important limitation of our study was the limited number of SES variables. Future studies should examine the impact of additional SES indicators, including those indicating objective and subjective material deprivation. Secondly, we have measured resources in terms of family SES (parental education and subjective material status of the family), but not personal SES. Interestingly, within resources model, there were nevertheless significant demographic predictors: women were found more frequently active on protest and civic participation dimensions, while older youth were found more frequently active on conventional and protest participation dimensions. Despite several limitations of the present study, it was nevertheless one of the few to test the Civic Voluntarism Model on a representative sample of youth from a postcommunist country. One of the prerequisites of democracy is not only democratic political culture, such as democratic values and attitudes (Inglehart in Welzel, 2007), but also pro-democratic behaviour. In this sense citizen participation is regarded as one of the most important elements of a functioning democracy (Almond and Verba, 1963; Pateman, 1970; Dahl, 1972; Barber, 1984). Democratic orientation and behaviour of public in postcommunist countries thus plays an important role for the democratic functioning and consolidation of younger democratic states. Understanding the predictors of citizen participation in new democracies, especially among youth, can thus shed light and contribute to continued and effective consolidation of postcommunist democracies. 1.6 Literature Almond, G. A., and Verba, S. (1963): The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Bäck, H., and Teorell, J. (2005): Party Attachment and Political Participation: A Panel Study of Citizen Attitudes and Behavior in Russia. Paper prepared for presentation at the Karlstad Seminar in Studying Political Action, June 7–9 2005. Badescu, G., and Neller, K. (2007): Explaining associational involvement. In J. W. van Deth, J. R. Montero, and Westholm, A. (Eds.): Citizenship and involvement in European democracies: a comparative analysis, 158-187. London, New York: Routledge. Barber, B. R. (1984): Strong democracy: participatory politics for a new age. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. Barnes, S., et al. (1979): Political Action: An Eight Nation Study. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social research. Besley, J. C. (2006): The Role of Entertainment Television and Its Interactions with Individual Values in Explaining Political Participation. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 11: 41–63. Bimber, B., Cantijoch Cunill, M., Copeland, L., and Gibson, R. (2014): Digital Media and Political Participation: The Moderating Role of Political Interest Across Acts and Over Time. Social Science Computer Review July 3, doi: 10.1177/0894439314526559 Brady, H., Verba, S., and Schlozman Lehman, K. (1995): Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation, American Political Science Review, 89 (1): 271–294. Burn, N., Lehman Schlozman, K., and Verba, S. (2001): The private roots of public action: gender, equality, and political participation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Cho Tam, W. K., Gimpel J. G., and Wu, T. (2006): Clarifying the Role of SES in Political Participation: Policy Threat and Arab American Mobilization. The Journal of Politics, 68 (4): 977–991. Conklin, D. (2008): The Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Political Participation: A MultiNational Analysis. Paper presented at 16th Annual Illinois State University Conference for Students of Political Science, April 4, 2008. Conway, M. M. (2000): Political Particiption in the United States (3 rd Edition). Washington, D. C.: CQ Press. Dahl, R. A. (1972): Polyarchy: participation and opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press. Dalton, R. J. (2008): The good citizen: how a younger generation is reshaping American politics. Washington (D.C.): CQ, Press. Dalton, R. J., and van Sickle, A. (2005): The Resource, Structural, and Cultural Bases of Protest Center for the Study of Democracy (University of California, Irvine). Accessed through http://escholarship.org/uc/item/3jx2b911 (21.03.2010). DiFranceisco, W., and Gitelman, Z. (1984): Soviet Political Culture and "Covert Participation" in Policy Implementation. The American Political Science Review, 78 (3): 603–621. Duch, R. (1998): Participation in New Democracies of Central and Eastern Europe: Cultural versus Rational Choice Explanations. In S. H. Barnes, in J. Simon, (Ed.): The postcommunist citizen, 195–228. Budapest: Erasmus Foundation. Fahmy, E. (2006): Young citizens. Young people’s involvement in politics and decision making. Burlington: Ashgate. Hadjar, A., and Beck, M. (2010): Who Does Not Participate In Elections In Europe And Why Is This? European Societies, 12: 521–542. Hutcheson, D. S., and Korosteleva, E. A. (2006): Patterns of Participation in Post-Soviet Politics. Comparative European Politics, 4: 23–46. Inglehart, R. (1997): Modernization and postmodernization: cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Princeton (New Jersey), Chichester: Princeton University Press. Inglehart, R., in Catterberg, G. (2002): Trends in Political Action: The Developmental Trend and the Post-Honeymoon Decline. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 43: 300– 316. Inglehart, R., in Welzel, C. (2007): Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: the human development sequence. New York: Cambridge University Press. Kaase, M., and Marsh, A. (1979): Political Action. A Theoretical Perspective. In S. Barnes, in M. Kaase, et al. (Eds.): Political Action: Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies, 2756. London: Sage. Kang, N. and Kwak, N. (2003): A Multilevel Approach to Civic Participation: Individual Length of Residence, Neighborhood Residential Stability, and Their Interactive Effects With Media Use: Communication Research, 30 (1): 80-106. Kirbiš, A. (2013): Determinants of political participation in Western Europe, East-Central Europe and post-Yugoslav countries. In Flere, S. (Ed.): 20 years later: problems and prospects of countries of former Yugoslavia, 177-200. Maribor: Center for the Study of Post-Yugoslav Societes, Faculty of Arts. Kirbiš, A., and Flere, S. (2011): Participation. In Lavrič, M. (Ed.): Youth 2010: the social profile of young people in Slovenia (1st ed), p. 187-259. Ljubljana: Ministry of Education and Sports, Office for Youth; Maribor: Aristej. Kirbiš, A., and Zagorc, B. (2014): Politics and democracy. In Flere, S. (Ed.): Slovenian youth 2013: living in times of disillusionment, risk and precarity, p. 211-243. Maribor: Centre for the Study of Post-Yugoslav Societies (CEPYUS), University of Maribor; Zagreb: FriedrichEbert-Stiftung (FES). Lavrič, M., Divjak, M., Naterer, A., in Lešek, P. (2011). Research methods. In Lavrič, M. (Ed.): Youth 2010: the social profile of young people in Slovenia (1st ed), p. 45-64. Ljubljana: Ministry of Education and Sports, Office for Youth; Maribor: Aristej. Leong, P. (2004): Race and Religiosity as Predictors of Political Participation. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, Hilton San Francisco & Renaissance Parc 55 Hotel, San Francisco, CA, Aug 14, 2004. Letki, N. (2004): Socialization for Participation? Trust, Membership, and Democratization in East-Central Europe. Political Research Quarterly, 57 (4): 665–679. Macaluso, T. F., and Wanat, J. (1979): Voting Turnout & Religiosity. Polity, (12) 1: 158–169. Macedo, S., Alex-Assensoh, Y., and Berry, J. (2005): Democracy At Risk: How Political Choices Undermine Citizen Participation And What We Can Do About It. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. Martin, I., and van Deth, K. (2007): Political involvement. In J. W. van Deth, J. R. Montero, and Westholm, A. (Eds.): Citizenship and involvement in European democracies: a comparative analysis, 303–333. London, New York: Routledge. McIntosh, H., Hart, D., and Youniss, J. (2007): The Influence of Family Political Discussion on Youth Civic Development: Which Parent Qualities Matter? Political Science and Politics, 40: 495–499. McLeod, J. M., Scheufele, D. A., and Moy, P. (1999): Community, communication, and participation: The role of mass media and interpersonal discussion in local political participation. Political Communication, 16 (3): 315-336. Mihailović, S. (1986): Odnos omladine prema politici. In S. Vrcan (Ed.): Položaj, svest i ponašanje mlade generacije Jugoslavije: preliminarna analiza rezultata istraživanja, 169-186. Beograd: Centar za istraživačku, dokumentacionu i istraživačku delatnost predsedništva. Mihailović, S. (1986): Odnos omladine prema politici. In S. Vrcan (Ed.): Položaj, svest i ponašanje mlade generacije Jugoslavije: preliminarna analiza rezultata istraživanja, 169-186. Beograd: Centar za istraživačku, dokumentacionu i istraživačku delatnost predsedništva. Milbrath, L. (1965): Political Participation. Chicago: Rand McNally. Norris, P. (2002): Democratic phoenix: reinventing political activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Norris, P. (ur.) (1999): Critical citizens: global support for democratic government. Oxford: Oxford University Press. O’Neill, B. (2009): The Media’s Role in Shaping Canadian Civic and Political Engagement. The Canadian Political Science Review 3 (2): 105-127. Pantić, D. (1988): Politička kultura i članstvo SKJ. In V. Falatov, B. Milošević, and R. Nešković (Eds.): Tito – partija, 489-509. Beograd: Memorijalni centar "Josip Broz Tito": Narodna knjiga. Pantić, D., and Pavlović, Z. (2009): Political culture of voters in Serbia. Beograd: Institut društvenih nauka. Parry, G., Moyser, G., in Day, N. (1992): Political participation and democracy in Britain. Cambridge [etc.]: Cambridge university press. Pasek, J., Kenski, K., Romer, D., and Hall Jamieson, K. (2006): America's Youth and Community Engagement: How Use of Mass Media Is Related to Civic Activity and Political Awareness in 14- to 22-Year-Olds. Communication Research, 33 (3): 115-135. Pateman, C. (1970): Participation and democratic theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Patterson, E. (2005): Religious Activity and Political Participation: The Brazilian and Chilean Cases. Latin American Politics and Society, 4 (1): 1–29. Quintelier, E. (2007): Differences in political participation between young and old people: A representative study of the differences in political participation between young and old people. Paper prepared for presentation at the Belgian-Dutch Politicologenetmaal 2007, Antwerp, Belgium, 31 May – 1 June 2007. Roller, E., and Rudi, T. (2008): Explaining Level and Equality of Political Participation. The Role of Social Capital, Socioeconomic Modernity, and Political Institutions. In H. Meulemann (Ed.): Social capital in Europe: similarity of countries and diversity of people?: Multi-level analyses of the European social survey 2002, 251–284. Leiden, Boston: Brill. Romer, D., Hall Jamieson, K., and Pasek, J. (2009): Building Social Capital in Young People: The Role of Mass Media and Life Outlook. Political Communication, 26:65–83. Rosenstone, S. J., and Hansen, J. M. (1993): Mobilization, Participation and Democracy in America. New York: Macmillan. Sandell Pacheco, J., and Plutzer, E. (2008): Political Participation and Cumulative Disadvantage: The Impact of Economic and Social Hardship on Young Citizens. Journal of Social Issues, 64 (3): 571–593. Scheufele, D. A. (2002): Examining Differential Gains From Mass Media and Their Implications for Participatory Behavior. Communication research, 29 (1): 46-65. Schlozman, Lehman K., Burns, N., Verba, S., and Donahue, J. (1995): Gender and Citizen Participation: Is There a Different Voice? American Journal of Political Science, 39, 267–293. Shin, Doh C. (1999): Mass politics and culture in democratizing Korea. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Shupe, A. D. Jr. (1977): Conventional Religion and Political Participation in Postwar Rural Japan. Social Forces, 55 (3): 613–629. Smith, M. L. (2009): The Inequality of Participation: Re-examining the Role of Social Stratification and Post-Communism on Political Participation in Europe. Czech Sociological Review, 3: 487–517. Smith, M. L. (2009): The Inequality of Participation: Re-examining the Role of Social Stratification and Post-Communism on Political Participation in Europe. Czech Sociological Review, 3: 487–517. Solhaug, T. (2006): Knowledge and Self-efficacy as Predictors of Political Participation and Civic Attitudes: with relevance for educational practice. Policy Futures in Education, 4 (3): 265–278. Spehr, S., and Dutt, N. (2004): Exploring Protest Participation in India: Evidence from the 1996 World Values Survey. African and Asian Studies, 3 (3–4): 185–218. Thomassen, J., and van Deth, J. W. (1998): Political involvement and Democratic Attitudes. V S. H. Barnes, in J. Simon, ( Ed.): The postcommunist citizen, 139–164. Budapest: Erasmus Foundation. Torney-Purta, J., and Richardson, W. (2002): Trust in Government and Civic Engagement among Adolescents in Australia, England, Greece, Norway and the United States. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Boston Marriott Copley Place, Sheraton Boston & Hynes Convention Center, Boston, Massachusetts, Aug 28, 2002. van Deth, J. W. (2008): Political involvement and social capital. In H. Meulemann (Ed.): Social capital in Europe: similarity of countries and diversity of people? Multi-level analyses of the European Social Survey 2002, 191–218. Leiden & Boston: Brill. Vassallo, F. (2006): Political Participation and the Gender Gap in European Union Member States. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 14 (3): 411–427 Verba, S., and Nie, N. (1972): Participation in America. New York: Harper & Row. Verba, S., Burns, N., and Schlozman Lehman, K. (2003): Unequal at the Starting Line: Creating Participatory Inequalities across Generations and among Groups. The American Sociologist, 34 (1/2): 45–69. Verba, S., Schlozman, K., and Brady, H. (1995): Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Zukin, C., Keeter, S., Andolina, M., Jenkins, K., and Delli Carpini, M. X. (2006): A New Engagement? Political Participation, Civic Life, and the Changing American Citizen. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Zukin, C., Keeter, S., Andolina, M., Jenkins, K., and Delli Carpini, M. X. (2006): A New Engagement? Political Participation, Civic Life, and the Changing American Citizen. Oxford: Oxford University Press.