Enzyme Kinetics: Michaelis-Menten & Reversible Reactions

advertisement

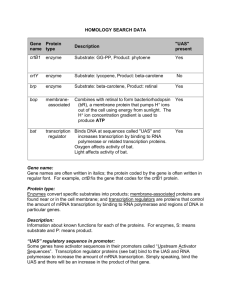

Wednesday 7th March, 2012 at 12:13 Noon Control Theory for Biologists, Draft 0.81 www.sys-bio.org 3 Basic Enzyme Kinetics 3.1 Enzyme Kinetics The vast majority of chemical transformations inside cells are catalyzed by enzymes. Enzymes accelerate the rate of chemical reactions (both forward and backward) without being consumed in the process and tend to be very selective, with a particular enzyme accelerating only a specific reaction. The model for enzyme action, first suggested by Brown and Henri but later established more thoroughly Michaelis and Menten, suggests the binding of free enzyme to the reactant forming a enzyme-reactant complex. This complex undergoes a transformation, releasing product and free enzyme. The free enzyme is then available for another round of binding to new reactant. Traditionally, the reactant molecule that binds to the enzyme is termed the substrate, S , and the mechanism is often written as: k1 k2 E C S )* ES ! E C P k (3.1) 1 This mechanism illustrates the binding of substrate and release of product, P . E is the free enzyme and ES the enzyme substrate complex. Note that 55 56 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS in this model substrate binding is reversible but product release is not. A more realistic mechanism will always have some degree of reversibility in product formation which leads to the following more general model: k1 k2 E C S )* ES )* E C P k 1 k 2 It is possible to model enzymes using the explicit mechanisms shown above, however the rate constants for the binding and unbinding reactions are either often unknown or difficult to determine. Instead, assumptions are made about the dynamics of the mechanism which reduces the number of constants required to characterize the enzyme. This leads to a discussion of aggregate rates laws, the most celebrated being Michaelis-Menten kinetics. 3.1.1 Michaelis-Menten Kinetics In practice we rarely build models using explicit elementary reactions unless it is absolutely necessary in order to capture a particular type of dynamical behavior. Quite apart from the huge increase in complexity, the rate constants for the elementary reaction are in any case usually not known. Instead we will often use approximations, sometimes called aggregate rate laws. If we consider first the fully reversible mechanism for enzyme action: k1 k2 E C S )* ES ! E C P k 1 Two different assumptions have been employed to reduce this scheme to a simpler formulation, the first termed rapid equilibrium was made in the original derivation by Michaelis and Menten. They assumed that the first step, that is binding of substrate to enzyme, was in equilibrium. The second approach was introduced by Briggs and Haldane, called the steady state assumption (Fig. 3.1) and in enzyme kinetics is the most commonly used approach. Rather than assume equilibration, Briggs and Haldane assumed that the enzyme substrate complex rapidly reached steady state. This was less restrictive that the rapid equilibrium assumption. Enzyme rate laws are often are derived using the steady state assumption, however 3.1. ENZYME KINETICS 57 Concentration 10 8 P 6 S 4 E 2 ES 0 0 0:2 0:4 0:6 0:8 Time 1 1:2 1:4 Figure 3.1: Progress curves for a simple irreversible enzyme catalyzed reaction (3.1). Initial substrate concentration is set at 10 units. The enzyme concentration is set to an initial concentration of 1 unit (E and ES curves are scaled by two in order to make the changes in E and ES easier to visualize). In the central portion of the plot one can observe the relatively steady concentrations of ES and E (dES=dt 0). At the same time, the rate of change of S and P are constant over this period. k1 D 20; k 20 1 10 * ES ! E C P D 1; k2 D 10, that is: E C S ) 1 because the mathematics can become complicated, many complex mechanisms, such as cooperativity and gene expression are still derived using the rapid equilibrium assumption. For this reason the rapid equilibrium derivation will be briefly described here. Rapid Equilibrium Assumption If we let Ks be the dissociation constant for binding: E:S Ks D ES and noting that the total concentration of enzyme, E t , is the sum of free enzyme, E and enzyme substrate complex, ES: E t D E C ES, it is easy to show that the equilibrium concentration of ES is given by: ES D Et : S Ks C S 58 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS Since the rate of reaction is determined by the rate of release of product, we can write down the rate of reaction as v D k2 ES. Combining this with the previous relation for ES, yields our result: vD E t : k2 S Ks C S Steady State Assumption Instead of assuming rapid equilibrium, let us follow the treatment of Briggs and Haldane by assuming that the enzyme substrate complex rapidly reaches steady steady. Fig 3.1 shows progress curves illustrating the changes in concentrations for the different enzymatic species. Note that the concentration of the enzyme substrate complex rapidly approaches a steady state and remains in this state until the substrate level reaches a low level. The rate of change of the enzyme substrate complex (??) can be written down using the laws of mass-action: d ES D k1 E : S dt k 1 ES k2 ES The concentration of enzyme substrate complex is assumed to rapidly reach steady-state (Fig. ??) so that the above equation can be set to zero: 0 D k1 E : S k 1 ES k2 ES We also note that the total concentration of enzyme, E t , is the sum of free enzyme, E and enzyme substrate complex, ES: E t D E C ES From these relationships, the steady-state concentration of enzyme substrate complex can be derived: ES D Et : S .k 1 C k2 /=k1 C S By assuming that the rate of reaction is given by v D k2 ES , we obtain: vD .k E t k2 S C k2 /=k1 C S 1 (3.2) 3.1. ENZYME KINETICS 59 The Vmax can be expressed as the total enzyme concentration times the rate constant for the product formation, E t k2 . We can also combine the constants .k 1 C k2 /=k1 into a single new constant called the Michaelis constant, or Km. Reaction Rate Vmax 1 0:8 0:6 0:4 0:2 0 0 5 10 Km 15 20 25 30 Substrate Concentration Figure 3.2: Relationship between the rate of reaction for a simple Michaelis-Menten rate law. The reaction rate reaches a limiting value (saturates) called the Vmax. Km is set to 4.0 and Vmax to 1.0. Note that the value of the Km is the substrate concentration that gives half the maximal rate. vD Vmax S Km C S (3.3) If we set the reaction velocity to half the Vmax, one can easily show that the Km is the substrate concentration that gives half the maximal rate (Figure. 3.2). Reversible Michaelis-Menten Rate law The derivation of the irreversible Michaelis-Menten is an instructive exercise, however it is not a particularly realistic model to use in models be- 60 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS cause there is no explicit product inhibition term. Instead, it is much better to consider the reversible Michaelis-Menten rate law. The derivation of the reversible form is very similar to the derivation of the irreversible rate law. The main difference is that the steady-state rate is given by an expression that incorporates both the forward and reverse rates for the product: v D k2 ES k 2 E:P The expression that describes the steady-state concentration of the enzyme substrate complex also has an additional term from the product binding (k 2 EP ). Taking these into consideration leads to the general reversible rate expression (See Appendix B for a full derivation): vD Vf S=KS Vr P =KP 1 C S=KS C P =KP At equilibrium the rate of the reversible reaction is zero. When positive the reaction is going in the forward direction and in the reverse direction when negative. At equilibrium the equation reduces to 0 D Vf Seq =KS Vr Peq =KP where Seq and Peq represent the equilibrium concentrations for substrate and product. Rearrangement yields Keq D Vf KP Peq D Seq Vr KS This expression is known as the Haldane relationship and shows that the four kinetic constants are not independent. The relationship can be used to eliminate one of the kinetic constants and substitute the equilibrium constants in its place. This is useful because equilibrium constants tend to be better known that kinetic constants. Incorporating the Haldane relationship yields the equation vD Vf =KS .S P =Keq / 1 C S=KS C P =KP Separating out the terms makes it easier to see that the equation has a thermodynamic term .S P =Keq / and a kinetic term as shown in the 3.1. ENZYME KINETICS 61 following expression: v D .S P =Keq / Vf =KS 1 C S=KS C P =KP The fact that the equilibrium constant appears are a constant factor in the expression suggests that enzymes do not change the equilibrium ratio, but simply accelerate the approach to equilibrium. Haldane Equilibrium Relations At equilibrium the net rate of reaction is zero. When the net rate is positive the reaction is going in the forward direction and in the reverse direction when negative. At equilibrium the reversible Michaelis equation reduces to 0 D Vf Seq =KS Vr Peq =KP where Seq and Peq represent the equilibrium concentrations for substrate and product. Rearrangement yields Keq D Vf KP Peq D Seq Vr KS This expression is known as the Haldane relationship and shows that the four kinetic constants are not independent and is directly related to the law of detailed balance that was introduced in section 2.2. The relationship can be used to eliminate one of the kinetic constants and substitute the equilibrium constants in its place. This is useful because equilibrium constants tend to be better known that kinetic constants. Incorporating the Haldane relationship yields the equation vD Vf =KS .S P =Keq / 1 C S=KS C P =KP Separating out the terms makes it easier to see that the equation has a thermodynamic term .S P =Keq / and a kinetic term as shown in the following expression: v D .S P =Keq / Vf =KS 1 C S=KS C P =KP 62 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS The fact that the equilibrium constant appears are a constant factor in the expression suggests that enzymes do not change the equilibrium ratio, but simply accelerate the approach to equilibrium. Product Inhibition Sometimes reactions appear irreversible, that is there is no discernable back rate, and yet the forward reaction is influenced by the accumulation of product. This effect is caused by the product competing with substrate for binding to the active site and is often called product inhibition. An important industrial example of this is the conversion of lactose to galactose by the enzyme ˇ galactosidase where galactose will compete with lactose and thereby slow the forward rate (Gekas and Lopex-Leiva, 1985). The reversible Michaelis-Menten rate law need not be used in these situations, instead a modified form of the irreversible rate law can be employed. The rate law below shows a simple modification to the irreversible rate law that accommodates product inhibition: vD Vm S S C Km 1 C P =Kp Further discussion on this is given in more detail in section ?? when discussing competitive inhibition. The steady-state approximation that allows us to derive convenient aggregate rate laws comes with a price. The approximation assumes that the amount of substrate sequestered by the enzyme is negligible compared to the free substrate. in vivo this assumption may not necessarily hold where enzyme concentrations can be comparable to substrate concentrations. Models that employ the Michaelis-Menten laws compared to explicit mass-action models can exhibit changes in their behavior. In particular the presence of high levels of enzyme substrate complex compared to free substrate can add buffering effects to the dynamics causing time delays in the evolution of the system. Fortunately the steady-state behavior will be largely unaffected except in some cases where the dynamic stability might change, for example leading to the onset of oscillatory behavior. Ideally one should check whether in a particular model the use 3.2. COOPERATIVE KINETICS 63 of Michaelis-Menten kinetics or any aggregate rate law has an effect on the model dynamics by comparing the model to one built using explicit mass-action rate laws. 3.1.2 Aggregate Rate Laws The steady-state approximation that allows us to derive convenient aggregate rate laws comes with a price. The approximation assumes that the amount of substrate sequestered by the enzyme is negligible compared to the free substrate. in vivo this assumption may not necessarily hold where enzyme concentrations can be comparable to substrate concentrations. Models that employ the Michaelis-Menten laws compared to explicit mass-action models can exhibit changes in their behavior. In particular the presence of high levels of enzyme substrate complex compared to free substrate can add buffering effects to the dynamics causing time delays in the evolution of the system. Fortunately the steady-state behavior will be largely unaffected except in some cases where the dynamic stability might change, for example leading to the onset of oscillatory behavior. Ideally one should check whether in a particular model the use of Michaelis-Menten kinetics or any aggregate rate law has an effect on the model dynamics by comparing the model to one built using explicit mass-action rate laws. 3.2 Cooperative Kinetics Many proteins are known to be oligomeric, that is they are composed of more than one identical protein subunit. For example, phosphofructokinase (E.C 2.7.1.11) from Escherichia coli is made of up four identical subunits. Each subunit has at least three binding sites corresponding to sites for ATP, Fructose-6-Phosphate (F6P) and one site for ADP and PEP. Both the F6P and ADP/PEP sites are on subunit boundaries, this means that their binding can change the binding affinities on the other subunits. In general subunits in an oligomer will have one or more ligand binding sites, which can, when occupied, affect the binding affinities in the other subunits. The ability of a ligand to affect the binding affinity of sites on the 64 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS other subunits is termed cooperative binding. If ligand binding increases the affinity of subsequent ligand binding, then it is termed positive cooperativity, otherwise it is called negative cooperativity. One of the characteristics of positive cooperativity on a reaction rate is to generate a sigmoid curve. Such a curve is illustrated in the figure below, a corresponding Michaelian curve is shown for comparison. Reaction Rate 1 0:8 0:6 0:4 0:2 0 0 0:5 1 1:5 2 2:5 3 Substrate Concentration Figure 3.3: Plot comparing positive cooperativity to a hyperbolic response. Hill Equation The Hill equation was originally derived empirically to describe the sigmoid character found in the binding of oxygen to hemoglobin. Only later was a mechanism proposed that might explain the relationship. The model however was simplistic, and even unrealistic, but it provided a baseline from which to compare other models. Consider an oligomer with n subunits and a binding site on each subunit for a ligand, S. If we make the assumption that when the first ligand binds, the binding affinity for the remaining n 1 sites change such that all the remaining ligands also bind simultaneously, then we can represent 3.2. COOPERATIVE KINETICS 65 this situation as follows: E CnS ! ES Assuming the rapid equilibrium assumption we can write: KD ES E : Sn where K is the association constant for ligand binding. Using the conservation relation E t D E C ES, the relative saturation can be shown to be given by: ES Sn Sn D D Et 1=K C S n Kd C S n This is the Hill equation where Kd is the dissociation constant. Often the Hill equation is represented in the following way in the literature: vD Vmax S n Kd C S n where Kd is the dissociation constant and h the Hill coefficient. Sometimes the equation is also expressed in terms of the half-maximal activity constant, KH . To do this we set the left-hand side to 0.5 and find the relationship between S and Kd . If we do this then we find: SD p n Kd p n p That is Kd is the half-maximal activity value, or KH D n Kd , that is n KH D Kd . We can therefore write the Hill equation in an alternative form as: vD Vmax S n Vmax .S=KH /n D n n KH C Sn 1 C KSH In the literature both forms are presented but they all have the same behavior. The equation in terms of the half-maximal activity has advantages because half-maximal activity can be measured directly from experiments. 66 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS If ligand binding acted in the way suggested in the derivation of the Hill equation, n would represent the number of binding sites, an integer. However, fitting the Hill equation to real data rarely gives integer estimates to n suggesting that the model is not a faithful representation of any real system. The utility of the Hill equation however lies in its ability to represent sigmoid behavior for simple cooperative systems such as transcription factor binding and as a result it has found wide spread use in modeling circles. However it is severely limited in other aspects, it is not possible to easily add regulator molecules to the equation or model multi-reactant systems and significantly it models an irreversible reaction. 1 nD8 nD4 Reaction Rate 0:8 nD2 0:6 0:4 0:2 0 0 0:5 1 1:5 2 2:5 3 Substrate Concentration Figure 3.4: Plot showing the response of the rate and elasticity for the Hill model, with n set to the indicated values and KH D 1. 3.2.1 Reversible Hill Equation In the enzyme kinetics literature much attention is paid to the molecular mechanisms that generate cooperativity. However for modeling purposes simple rate models such as the the Hill equation can be sufficient. However the main problem with the Hill equation is that it describes an irreversible 3.2. COOPERATIVE KINETICS 67 reaction. In recent years, Hofmeyr and Cornish-Bowden published a description of the reversible Hill equation with modifiers. The general form of the reversible Hill equation without modifiers is given by: Vf vD S Ks S P C Keq Ks Kp h S P 1C C Ks Kp h 1 1 Figure 3.5 illustrates the sigmoid behavior with respect to the substrate concentration. The K constants in the equation are the half saturation constants. is the mass-action ratio and Keq the equilibrium constant for the reaction. What is significant about this formulation is that the thermodynamic terms are separated from the saturation terms, a structure also found in all the variants. The equation also reduces to familiar forms when certain restrictions are applied. For example if h D 1 the equation reduced to the non-cooperative reversible Michaelis rate law and of course if reversibility is removed as well the equation reduces to the simple irreversible Michaelis-Menten rate law. The equation can also revert to the product inhibited but irreversible rate law by setting the Keq to infinity. The reversible Hill equation is therefore quite flexible and can be used in my situations. When modifiers are included an additional term appears in the denominator. In the equation below the modifier is indicated by the symbol M . The ˛ term can be used to determine whether the modifier is an activator or an inhibitor. If ˛ < 1 then the modifier acts as an inhibitor otherwise it acts as an activator. S S P h Vf 1 C Ks Keq Ks Kp vD h 1 C KMm S P h C C h Ks Ks 1 C ˛ KMm 1 68 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS ˛<1 inhibitor ˛>1 activator 1 Reaction Rate 0:8 0:6 Ks = 1 4.0 2.4 0:4 0:2 0 0 2 4 6 8 Substrate Concentration Figure 3.5: Plot showing the response of the reaction rate for a reversible Hill model with respect to the substrate as a function of the substrate Michaelian constant. In this a the next figure, the parameters were set as follows: V m D 1; D 2; Keq D 10:95; Kp D 0:5; n D 4:85; Ke D 2:75; ˛ D 10 5 , P = 0, M = 0 The reversible Hill equation also shows one additional property. Under a certain set of parameter values, the product concentration can act as a positive regulator (Figure ??). The possibility of positive activation can lead to some interesting behavior which we will return to in a later chapter. Hanekom ?? derived (along with many other variants) a generalized uniuni reversible Hill equation that incorporated multiple modulators: 3.2. COOPERATIVE KINETICS 69 0:5 Reaction Rate 0:4 0:3 0:2 Ke = 1.2 2.0 4.2 0:1 0 0 2 4 6 8 Inhibitor Concentration Figure 3.6: Plot showing the response of the reaction rate for a reversible Hill model with respect to the inhibitor concentrations as a function of the inhibitor Michaelis constant. Ks D 2; S D 1, all other parameter were identical to the previous figure. Vf ˛ 1 C Keq .˛ C /h 1 vD Qnm 1Ch i C .˛ C /h h i D1 1Ci i To simplify the notation in the above equation, ˛ D S=Ks , D P =Kp and D M=Km . is the modifier factor that determines whether the modifier is an activator (> 1) or an inhibitor. Kx are the Michaelian constants, S the substrate, P the product and M the modifier. This equation assumes that each modifier binds independently of the other, that is the binding of one modifier does not affect the binding of any other. 70 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS 3.3 Multiple Substrate Enzymes It is probably fair to say that most enzyme catalyzed reactions involve two substrates. For example, all oxidoreductases involve two substrates, one an oxidant and the other a reductant. Even apparently single substrate reactions may actually involve water as a second substrate which we choose to ignore because we assume that the concentration of water hardly changes during the reaction. The world of two substrate kinetics is however far more complex than single substrate kinetics. There are more possible variations in the rate laws particularly when we consider how the substrates bind and products leave the active site. The commonest reaction mechanisms include compulsoryorder, when one substrate must bind before the other, random-order where substrates can bind in any order and double-displacement where one substrate binds, modifies the enzyme then leaves to allow the other substrate to bind. These different mechanisms can generate subtlety different rate laws. The question however is whether such subtlety is significant when modeling pathways? For those interested in catalytic mechanisms, the difference in rate laws allow one to distinguish between the mechanisms and is thus an important consideration. For modeling, the need to be so precise is not so clear. Given the imprecision in kinetic data and the robustness of pathways to parameter variation, such subtleties may not in fact be important. As a result some authors suggest the use of generalized rate laws for modeling two substrate/product enzyme reactions. A number of these generalizations exist in the literature although they are all closely related to each other. For example, a generalized irreversible two substrate rate laws was introduced by Alberty in 1953: vD Vm AB KB A C MA B C AB C KiA KB where KA and KB are Michaelian constants and KiA is a dissociation constant. A useful reversible rate law is given by: 3.3. MULTIPLE SUBSTRATE ENZYMES Reaction Scheme Rate Law A$B Vf ˛ Vr ˇ 1C˛Cˇ ACB $C Vf ˛ ˇ Vr 1C˛CˇC˛ ˇC ACB $C CD Vf ˛ ˇ Vr ı 1C˛CˇC˛ ˇC CıC ı 71 Table 3.1: Generalized rate equations where Vf and Vr represent the forward and reverse Vmax values and the greek symbols such as ˛, represent the species concentrations divided by the Michaelisn constant, for example: ˛ D A=KA . Vm A B P Q 1 Keq A B KA KB vD A Q B P 1C C 1C C KA KQ KB KP which uses the Haldane relationships to eliminate parameters in favor of introducing the equilibria constant, Keq . Leibermeister and Klipp describe what they called ‘convenience kinetics’ which is a further generalization that includes a range of different stoichiometric reaction schemes some of which are given in the table below. Of more interest is the reversible Hill equation described in the last section. The reversible Hill equations can be generalized to accommodate many different possibilities, including multi-substrate, multi-modulators and irreversibility. 72 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS 3.4 Gene Regulatory Rate Laws Rate laws associated with gene regulation will only be covered briefly here. The companion book, Enzyme Kinetics for Systems Biology has a much more extensive discussion with an entire chapter devoted to rate laws used for modeling gene expression and regulation. 3.4.1 Structure of a Microbial Genetic Unit In this chapter we address exclusively prokaryotic gene regulation because it is much simpler than eukaryotic systems. However, many of the basic principles still apply to both groups of organism. The fundamental functional unit of the bacterial genome is the operon which consists of a control sequence followed by one or more coding regions. The control sequence has a promoter together with zero or more operator sites (Figure 3.7). The promoter is the specific sequence of DNA recognized by RNA polymerase which in turn is responsible for transcribing the DNA coding sequence into messenger RNA (mRNA). The binding of proteins called transcription factors (TF) to the operator sites are responsible for influencing the binding of RNA polymerase and thus can modulate mRNA production. Operators ... Operators ... Promoter One or More Coding Sequences Figure 3.7: Generic Bacterial Operon comprising of one or more coding sequences, one promoter site for RNA polymerase binding, and zero or more operator sites that may be upstream or downstream of the promoter. Operator sites that act as repressors are often found to overlap with the promoter site. Two other components are not shown in Figure 3.7, these include the ribosome binding site (RBS) and the terminator. The RBS is often a six to seven base nucleotide base sequence located about eight nucleotides upstream from the coding sequence start codon and is used by the ribosome 3.4. GENE REGULATORY RATE LAWS 73 as a recognition site. The other component, the terminator, is used to stop mRNA transcription at the end of the coding sequence. Binding of transcription factors results in the activation or inhibition of gene transcription. Multiple transcription factors may also interact to control the expression of a single operon. These interactions can emulate simple logical functions (such as AND, OR, etc.) or more elaborate computations. Gene regulatory networks range from a single controlled gene to hundreds of genes interlinked with transcription factors forming a complex, decision making network. Different classes of transcription factors also exist. For example, the binding of some transcription factors is modulated by small molecules, a well known example being the binding of allolactose (a disaccharide very similar to lactose) to the lac repressor or cAMP to the catabolite activator protein (CAP), also known as the cAMP receptor protein (CRP). Alternatively, a transcription factor may be expressed by one gene and either directly modulate a second gene (which could be itself) or via other transcription factors. Additionally, some transcription factors only become active when phosphorylated or unphosphorylated by protein kinases and phosphatases (Figure 3.9). The size of gene regulatory networks vary from organism to organism. The genome of E. coli for example encodes for approximately 171 transcription factors [19]. These proteins directly control all levels of gene expression. The EcoCyc [19] database reports at least 48 small molecules and ions that also influence transcription factors. The most extensive gene regulatory network database is RegulonDB [16, 12] and another associated network database EcoCyc [19]. RegulonDB is a database on the gene regulatory network of E. coli. More detail on the structure of regulatory networks can be found in the work of Alon [35] and Seshasayee [34]. 3.4.2 Gene Regulation Gene expression rates are controlled by transcription factors, RNA polymerase, and proteins called factors. factors are transcriptional initia- 74 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS tion proteins that influence the binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter and can be thought of as global signals that are synthesized in response to specific environmental conditions. Of more interest here is the role of transcription factors. These proteins either enhance or reduce the ability of RNA polymerase to bind to the promoter region and commence transcription. Transcription factors operate by recognizing and binding to specific DNA sequences on the operator sites. When transcription factors bind to operator sites they either block or help RNA polymerase bind to the promoter. At the molecular level, it is assumed that a given transcription factor will bind and unbind at a rapid rate. To quantify how transcription factors influence gene expression it is important to consider the state of an operator site. For a single transcription factor that can bind to a single operator site, there are two states, designated either bound or unbound (Figure 3.8). a) Unbound State Operator Promoter Coding Sequence b) Bound State TF Figure 3.8: Transcription Factor (TF) Bound and Unbound States. If the operator site can enhance RNA polymerase binding then the bound state is considered the active state and the unbound state the inactive state. If the operator is an inhibitory site then the bound state is the inactive state and the unbound state the active state. Some bacterial transcription factors such as the lactose repressor (LacI) are present at very low levels, on the order of 5 to 10 copies per cell [?, ?]. It is therefore appropriate to consider the probability that a given transcription factor is bound to an operator site. The state of an operator site can be described in terms of this probability. These probabilities are influenced by the association constant of binding, the availability of transcription factors, 3.4. GENE REGULATORY RATE LAWS 75 and other regulators. Gene Activation Gene Repression Multiple Control Gene Cascade Auto-Regulation Regulation by Small Molecule ~P Regulation by Phosphorylation Figure 3.9: Various Simple Gene Regulatory Motifs. Once bound, the transcription factor influences the probability of RNA polymerase binding to the promoter site. There are many mechanisms by which transcription factors can influence RNA polymerase. One of the simplest is for a transcription factor to bind to the promoter site itself, and by an act of exclusion, prevent the RNA polymerase from binding. Such transcription factors act as repressors. A similar effect occurs if a transcription factor binds downstream of the promoter site (closer to the start of the coding sequence). This prevents the RNA polymerase from moving into the coding sequence by either physical obstruction or because 76 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS the transcription factor has formed DNA loops. a) Downstream Obstruction RNA Pol TF Promoter Operator Coding Sequence b) Promoter Obstruction TF c) Sequestration of an activator resulting in inhibition TF TF RNA Pol RNA Pol RNA Polymerase TF “Activator” Repressing Transcription Factor Figure 3.10: Obstruction, exclusion and sequestration models for repressing gene expression. Examples of downstream obstruction include the galR and galS operators, where both operators are located beyond the promoter site [?]. LacI is a good example of promoter exclusion although the LacI repressor only overlaps about 40% of the promoter. Another mechanism for repression is by sequestration. This is rarer but one example is CytR repressed promoters. The CytR protein can form a dimer with CRP (which itself is a transcriptional activator). Once the dimer is formed, CRP is unable to bind, therefore inhibiting expression [?]. Activation by transcription factors is more subtle. One mechanism is for a transcription factor to bind upstream, close to the promoter site. In this in- 3.4. GENE REGULATORY RATE LAWS 77 stance the transcription factor can offer a suitable but weak molecular face for the RNA polymerase to bind (Figure 3.11). This allows RNA polymerase to stay on the promoter longer and therefore increases the probability of transcription. For example, weak binding may occur between hydrophobic areas on both proteins. An example of an activating TF is CRP on the lac operon. The CRP binding site is located only 15 bases upstream from the lacI promoter (Figure ??). Binding of CRP to its binding site allows the flexible RNA polymerase domains, ˛C TD and ˛N TD to bind to CRP, thereby increasing the likelihood of RNA successfully binding to the promoter site. Transcription factors themselves can be controlled by other transcription factors binding to operator sites. Control can also be accomplished by other proteins binding to the transcription factor or by small molecules, called inducers, that bind to the transcription factor and alter the operator binding affinity. LacI is an example of a transcription factor where the inducer molecule allolactose can bind, thereby altering the binding affinity of LacI. CI from the virus, lambda phage is an example of a transcription factor where control is exerted by influencing its production rate. 3.4.3 Fractional Occupancy One of the most important concepts to consider when quantifying how transcription factors influence gene expression is the fractional occupancy or degree of saturation at the operator site. This quantity expresses the probability of a particular occupancy relative to the total of all occupancy states. A simple example best describes this concept. Transcriptional Activation Consider a single operator site upstream of a promoter (Figure 3.11 and 3.12). The operator site binds a single monomeric transcription factor, A. Assume that when the transcription factor binds to the operator, the RNA polymerase has a higher probability of binding to the promoter site by virtue of complementary patches on the RNA polymerase and transcription factor. If we assume the rate of gene expression is proportional 78 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS a) Activation by RNA polymerase requitment TF RNA Pol Operator Promoter Coding Sequence b)Sequestration of a repressor resulting in activation TF RNA Pol TF TF Transcription Factor RNA Pol RNA Polymerase Figure 3.11: Gene regulation by an activating transcription factor. a) The operator site is upstream of the promoter, binding of the transcription factor increases the likelihood of RNA polymerase binding by way of weak interactions between the transcription factor and RNA polymerase. Alternatively, b) an activator can sequester a repressor transcription factor. to the probability of bound RNA polymerase, and that RNA polymerase has a constant concentration and activity in the cell, then we can assume the fractional occupancy of the transcription factor is proportional to gene expression. Let us designate the concentration of the unbound operator site by the symbol U , the bound operator site by the symbol AU and the free transcription factor by A as shown in Figure 3.12. The fractional occupancy of the operator site is then given by the degree of bound operator relative to the total of all occupancy states, that is: f D AU U C AU If we assume the rate of binding and unbinding of transcription factor to the operator site is much faster than transcription, then we can also assume 3.4. GENE REGULATORY RATE LAWS 79 U Operator AU Coding Sequence A A Transcription Factor Figure 3.12: Bound (AU) and unbound (U) states for a simple transcriptional activation model. the binding and unbinding process is at equilibrium. That is, the following process is at equilibrium: U C A AU We can express the equilibrium condition using the association constant, Ka , where: AU Ka D U A Given this information we can express AU in terms U : f D Ka U A U C Ka U A (3.4) The unbound state, U , can now be eliminated to yield: f D Ka A 1 C Ka A (3.5) We have seen this same approach when using the rapid equilibrium assumption from enzyme kinetics. Much of the following should therefore be familiar. Relation (3.5) yields a value between zero and one. Zero indicates an unbound state, and one indicates the operator site is fully occupied. To obtain the actual rate of expression, assume the rate is linearly proportional to the fractional occupancy, so that: v D Vm Ka A 1 C Ka A (3.6) 80 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS where Vm is the maximal rate of gene expression (Figure 3.13). Equation (3.6) yields a familiar hyperbolic plot. Gene Expression Rate, v 1 0:8 0:6 0:4 0:2 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 Transcription Factor Concentration Figure 3.13: Gene expression rate as a function of a monomeric transcription factor that activates gene expression. The association constant, Ka , has a value of 1. The reaction rate is normalized by Vm . If the association constant Ka is substituted by the dissociation constant (Ka D 1=Kd ), then we obtain: v D Vm A Kd C A (3.7) At half saturation it is easy to show that Kd D A. This result provides a simple way to estimate the Kd from a binding curve by locating the halfsaturation point and then reading the corresponding transcription factor concentration. Transcriptional Repression Repression can be handled in a similar manner. In this case we note that the active state is now the unbound state, U , so the fractional occupancy is 3.4. GENE REGULATORY RATE LAWS 81 given by: f D U U C AU Using the same equilibrium relation as before, we obtain (Figure 3.14): v D Vm 1 1 C Ka A (3.8) Gene Expression Rate, v 1 0:8 0:6 0:4 0:2 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 Transcription Factor Concentration Figure 3.14: Gene expression rate as a function of a monomeric transcription factor that represses gene expression. As with the activation example in the last section, the dissociation constant, Kd , is equal to the transcription factor concentration at half saturation. The companion book, Enzyme Kinetics for Systems Biology covers additional topics such as multi-transcriptional control and cooperativity in gene regulation. 82 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS 3.5 Generalized Rate Laws 3.5.1 Power Laws There are a number of approximate rate laws that have been used in past models. The simplest approximation is the power law which takes the form: vi D ˛i Y Sj "ji The " term is the kinetic order or elasticity and can and often is a noninteger. Negative values for " can be used to indicate inhibition. The advantage of the power law equation over the simpler linear rate law is that it shows a curvature reminiscent of an enzyme kinetic response. However the function does not saturate and this is one of its main drawbacks. It has found extensive use in Biochemical Systems Theory which was developed by Michael Savageau. 3.5.2 Linear-Logarithmic Rate Laws An improved approximation over the power law is the linear-logarithmic approximation (or linlog for short). One of the main limitations of the power law approximation is that there is no saturation effect at high reactant concentration whereas lin-log kinetics will show some degree of saturation. The general form of the equation is given by: v D vo e eo X S 1C " ln So where S is the reactant concentration and " the elasticity. The rate law is always defined around some reference state, a reference rate, vo and a reference reactant concentration, so . The utility of this approximation is that the values of the elasticities (kinetic orders) can to some extent be estimated from the known thermodynamic properties of the reaction. The values of the elasticities will be a function of the reference state. If no thermodynamic information is available then the elasticities can even be 3.5. GENERALIZED RATE LAWS 83 set to the stoichiometries of the respective reactants. In either case it is important that the lin-log approximation is only valid around the chosen reference state and also depends on how much the reactant levels diverge from the references during a simulation and the degree to which the elasticities are affected. A sensitivity analysis can be made to ascertain these details. An example of how to set a lin-log rate law is given in a subsequent section on elasticities. The companion book, Enzyme Kinetics for Systems Biology has a much more extensive discussion of rates including additional sections on other generalized rate laws. 3.5.3 Choosing a suitable Rate Law Given the huge range of possible rate laws, the novice modeler might seem at a loss to know which rate law to select for a given reaction step. However, before a model is built, its purpose should be clearly understood because that will help decided on the types of rate laws to employ. Ultimately models only have two functions: 1) Describe known observations and 2) Make new non-trivial predictions. So long as these requirements are satisfied the model is useful. It is often the case that novice modelers will feel it necessary to add every small detail into a model when in fact much of the detail can be dispensed. A model is a simplification of reality not a replica and the art of building models is knowing what details can be left out and what details are necessary. The question whether a particular reaction should use a specific pion-pong based rate law or a generalized rate law depends on how this choice determines the behavior of the model particularly within the constraints of measurements. A useful strategy is to carry out a sensitivity analysis to determine how much influence parameters or particular rate laws have on the dynamics of a model. If a particular parameter has little influence then there is no need to obtain a precise value for it while if a particular ate law has little influence than a simpler rate laws can be used instead which will often have much few parameters to set. It might be possible to use lin-log rate laws at many reaction steps while certain steps require a much more detailed description. As more detailed measurements become available it might be found that 84 CHAPTER 3. BASIC ENZYME KINETICS some of the lin-log approximations are too approximate and subsequent experimental efforts can focus on the descriptions at those particular steps. Exercises 1. In the steady state derived Michaelis-Menthen equation, what units does the Km have? 2. What is the concentration of substrate that yields half the reaction velocity for an irreversible Michaelis-Menten rate law? 3. An enzyme has a Vm of 10 mmols 1 mg 1 . The substrate Km is 0.5 mM. What is the initial rate when the substrate concentration is 0.5 mM and 5 mM? 4. At low substrate concentration is the order of the reaction, zero, first or second order? 5. Do enzymes change the equilibrium constant for a reaction? 6. List the assumptions made when the Michaelis-Menten equation is derived using the steady state assumption. 7. Using the irreversible Hill equation, show that thepsubstrate concentration at half the maximal velocity is given by n Kd where Kd is the dissociation constant and n the Hill coefficient. 8. Show that the reversible Hill equation reduces the the irreversible Hill equation when the product P is set to zero.