Patron-Client Politics in Hong Kong - HKU Scholars Hub

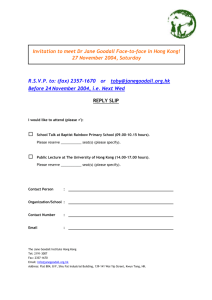

advertisement

Title

Author(s)

Patron-client politics in Hong Kong

Kwong, Kam-kwan.; 鄺錦鈞.

Citation

Issued Date

URL

Rights

2004

http://hdl.handle.net/10722/52457

The author retains all proprietary rights, (such as patent rights)

and the right to use in future works.

Patron-Client Politics in Hong Kong

By

Kwong Kam Kwan

( f l a m

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for

the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

at the University of Hong Kong

2004

Declaration

I declare that this thesis represents my own work, except where due

acknowledgement is made, and that it has not been previously included in a thesis,

dissertation or report submitted to this University or to any other institution for a degree,

diploma or other qualifications.

Signed

Kwong Kam-kwan

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to a number of people who gave me support in the progress of

completing the thesis. My fellow colleagues Mr. Eilo Yu Wing-yat, Mr. Benson Wong

Wai-kwok and Mr. Cheung Yat-fung, who have given me a lot of insightful comments

on my topics. The co-working spirits we have been experienced over the years at the

University of Hong Kong and our brotherhood-like friendship gained are unforgettable.

I must thank several Legislative Councilors for granting me in-depth interviews,

including Mr. Lee Wah-ming, Mr. Chan Wai-yip, Miss Choi So-yuk and Mr. Tang

Siu-tong. I cannot name other district-level activists who gave me inside information,

but their help was indispensable to the completion of my thesis. Thanks are also due to

all those political elites who answered my questionnaires on the Chief Executive

election, Legislative Council elections and District Council elections. Without their

support, my empirical data could not have been enriched considerably.

Finally, I must extend my gratitude to my girlfriend, who has supported and

encouraged me all the time, and helped me take care of my four lovely puppies when I

was crazily constructing this thesis.

Last but not least, I must make use of this opportunity to express my most sincere

appreciation and graceful heart to my respectful supervisor, Professor Sonny Lo

Siu-hing, who has taught me the insightful knowledge in political sciences as well as

public administration.

in

Abstract of thesis entitled

"Patron-Client Politics in Hong Kong

Submitted by

Kwong Kam-kwan

For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

at the University of Hong Kong

in 2004

This thesis proves that patron-client relations are indispensable to all levels of Hong

Kong's election, including the elections held for the Chief Executive, Legislative

Council, District Councils, grassroots level institutions such as MACs, HYK and

pro-Beijing district groups. Patron-client relations have varying degree of significances

in these four levels of elections. Patron-client network plays a critical role in Chief

Executive election. However, patron-client relations tend to assume a lesser importance

in Legislative Council's direct elections because of the larger geographical

constituencies, although ren-ch'ing and guanxi are still crucial in the candidates'

campaign for functional constituencies election.

At the grassroots level, clientelism is crucial for political party members to

penetrate housing groups, such as MACs and OCs. Due to the fact that the geographical

constituencies in District Council elections are smaller than LegCo's direct elections,

patron-client politics tends to be a decisive factor shaping candidates' chances of

electoral victory at the district level. Though the 2003 District Council elections saw a

decline in the impact of patron-client relations, patronage politics still persists in MACs,

HYK and pro-Beijing group mobilization of voter registration in the 2004 LegCo's

direct elections.

In short, patron-client relations are particularly prominent in CE election, LegCo's

functional constituency elections and party infiltration into housing organizations at the

grassroots level.

Table of Contents

Declaration

Acknowledgements

Tables of Contents

List of Illustration

Abbreviations

Chapter 1

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

1.6

Chapter 2

2.1

2.2

2.3

2.4

Chapter 3

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

3.5

3.6

3.7

1

ii

iv

vii

x

Introduction

Introduction

Patron-Client Politics From British Hong Kong Colony to

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China

The Concept of Patron-Client Politics

Research Hypotheses and Arguments in the Thesis

Research Methodology

Summary

Toward An Analytical Framework of Analysis

Introduction

The Existing Literature on Patron-Client Relations

An Analytical Framework of Patron-Client Politics

Summary

Patron-Client Relations and Public Administration

Introduction

Public Administration and Patron-Client Relations

Appointment System from the Colonial Era to Post-Colonial

Era

The Politics of HKSAR Awards in Advisory Bodies

Corruption, Patron-client Politics and Public Administration

Beijing's Patronage and Its Impact on Hong Kong's Politics

and Public Administration

Summary

IV

1

2

6

30

32

34

35

37

59

72

74

74

89

95

100

106

113

Chapter 4

4.1

The Chief Executive Election and Patron-Client Politics

Introduction

Patron-Client Politics in the First CE Election

The 2002 CE Election

Survey Findings on the Second CE Election in 2002

Summary

114

117

126

132

149

Chapter 5

5.1

5.2

5.3

5.4

The Legislative Council Election and Patron-Client Politics

Introduction

Interview with Legislative Councilors

Survey Results

Summary

153

156

161

184

Chapter 6

District Council Elections and Grassroots Level Politics

Introduction

Role of District Councilors

The 1999 and 2003 District Councils Elections

MACs and Patron-Client Relations

The Case of Tseung Kwan O Women Center

Case Study of Patron-Client Relations: District Council

Candidate and MAC in Kowloon City Constituency

Heung Yee Kuk (HYK) and Patron-Client Politics

The Cases of Chan Yat-sun and Lau Wong-fat: Clients of the

Colonial Government and the HKSAR Administration

Summaty

4. 2

4.3

4.4

4.5

6.1

6.2

6.3

6.4

6.5

6.6

6.6

6.7

6.8

Chapter 7

7.1

7.2

7.3

Conclusion

The significances of patron-client relations in the election

Scott's Features of Patron-Client Politics and the Hong Kong

Case

The Past, Present and Future of Patron-Client Politics in Hong

Kong

186

186

187

197

199

203

207

210

215

216

218

221

Appendices

Bibliography

224

238

vi

List of Illustrations

Figures:

1.1

2.1

2.2

3.1

4.2

6.1

6.2

6.3

6.4

Patron-Client Cluster and Pyramid

Simple factions and support structures in Hong Kong

The Dynamics of Patron-Client Politics in Hong Kong

Sources and Types of Ethical Responsibility

Profiles of Selected Members of the Preparatory Committee in

1996

Profile 1: Maria Tam

Profile 2: Tam Yiu Chung

Profile 3: Leung Chun Ying

Profile 4: Lee Chak Tim

Profile 5: Raymond Wu Wai Yung

Profile 6: Fong Wong Gut Man

Profile 7: Arthur Lee Kwok Cheung

Profile 8: Paul Ip Kwok Wah

Patron-Client Relations Pyramid in District Council Elections

Patron-Client Pyramid in MAC Level

Patron-Clientelist Ties of Local Politics revealed by Tseung Kwan

0 Women Centre

Institutional Privileges of Indigenous Inhabitants

Vll

10

45

58

77

119

119

119

120

120

121

121

122

122

191

197

202

207

Tables:

1.1

1.2

1.3

2.1

4.1

4.2

4.3

4.4

Three Orders of Political Relations

Exchange of Benefits

Survey on 17 Most Prestigious Occupations in Hong Kong

Pattern of Beneficiaries from Corruption in Less Developed

Nations

Changes in Loyalty Ties and Party Inducements

The Relationship Between Loyalty Bonds and Party Inducements

Personalistic ties in the First Grand Bauhinia Medal (GBM)

Award

Benefits of Li Ka Shing under the Tung Regime

The course of TVB in getting benefits through its communications

with Tung Chee-hwa

Run Run Shaw's dyadic ties with Tung Chee-hwa

Profile of Local Elites Co-opted into Chinese Consultative

Organizations

Members in an Advisory Body violating the "6-year rule"

List of Appointed DC councilors with patriotic organization

background

Exchange of Benefits

Four Sectors of the Election Committee

Election Members' Attitude Toward Criticism of Tung.

Nomination of Tung as Candidate

129

134

136

137

4.5

4.6

Factors of Nominating Tung

Expectations of Election Committee Members

137

138

4.7

4.8

4.9

Political Expectation of Election Committee Members

How did you know the candidate, Mr. Tung

The Legislative Councilors elected through Election Committee,

can play a check and balance role in the Council

As Mr. Tung was the only candidate in the CE election, the

majority of nomination can help to increase his legitimacy

The majority of nomination can help Mr. Tung to build up a

strong government

139

140

141

2.2

2.3

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

3.5

3.6

3.7

4.10

4.11

Vlll

13

27

29

52

53

54

82

85

87

88

92

98

99

141

142

4.12

4.13

4.14

4.15

4.16

4.17

5.1

5.2

5.3

5.4

5.5

5.6

5.7

5.8

5.9

5.10

5.11

5.12

5.13

5.14

The EC should expand the number of membership so as to

increase its legitimacy

The EC should add more representatives from other subsectors to

increase its legitimacy

Mr. Tung should appoint EC members, who had nominated him,

into advisory bodies or even the principle officials as a means of

reward

The EC membership can help you to upgrade your political

attainment. Do you agree with this statement

Expectations of Election Committee Members on Tung on their

role in the government

Appointment concerning the EC electors at different levels

What factor(s) made you won the 2000 Legco election?

Some scholars have identified the following factors may drive to

the electoral victory of a candidate, which of the factor(s) you

agree with

Do you think that social network is important to campaign

engineering

Do you think that social network is important to campaign

engineering

How do you construct connection with the voters

If you have sponsored activities, what kind of sponsorship you

adopted

It will be a major reason of losing votes in the absence of building

up good personal relations with voters

Concentrating on managing complaint and committee work is the

best way to build up the relation networks at the local level

On basis of the activities you organized to maintain relations with

voters, how do the voters respond

Which of the following group(s) you have maintained good

relations with

Which of the following group(s) assisted in your campaign

activities

How do they assist your campaign activities

Why do these groups agree to help you

The voters vote for you or your political party

IX

143

144

144

144

145

146

162

163

163

164

164

165

166

166

166

167

167

168

169

170

5.15

5.16

5.17

5.18

5.19

5.20

5.21

5.22

5.23

5.24

5.25

5.26

5.27

5.28

5.29

6.1

6.2

6.3

6.4

6.5

6.6

6.7

It will be a major reason of getting lesser votes without building

up a good local connection networkl71

To sponsor local organizations' activities is a must in a district

level work

To sponsor local organizations' activities is the best way to build

up a good local connection network

A District Councilor can effectively help to strengthen personal

relationship with voters

Local organizations/societies can effectively help to strengthen

personal relationship with voters

I can effectively strengthen personal relationship with voters

myself without the assistance of local organizations/societies

In short, guanxi and social network stand in a very important

position in electoral engineering

A Comparison of the 1998 and 2000 Legislative Council's

Election Results

The 2000 LegCo Election Results in Functional Constituencies

and the Election Committee

The Education Level of DP and DAB's Supporters

The Class Background of DP and DAB's Supporters

Self-Identification of DP and DAB's Supporters

Voting Considerations of DP and DAB's Supporters

(November 2003) Are you currently satisfied or dissatisfied with

both Central and HKSAR governments

(April 2004) Are you currently satisfied or dissatisfied with both

Central and HKSAR governments

Comparative voter turnout rates in 1999 and 2003 District Council

Election

Comparative Result of Political Parties in DC Election 1999 and

2003

Exit poll at King Lam Estate, TKO on November 23, 2003

What factors make you consider to vote for that candidate?

You vote for the candidate or political party?

If you can select, what kind of candidate is your ideal type?

Which category of person has mobilized you or your family to

vote for a specified candidate?

171

171

171

172

172

173

173

175

177

179

179

180

181

182

183

188

189

193

194

195

195

196

Abbreviations

ADPL

Association for Democracy and People's Livelihood

CCP

Chinese Communist Party

CE

Chief Executive

CF

Civil Force

CPPCC

Chinese People's Political Consultation Conference

DAB

Democratic Alliance for Betterment of Hong Kong

DC

District Council

DP

Democratic Party

HKPA

Hong Kong Progressive Party

HKSAR

Hong Kong Special Administration Region

HYK

Heung Yee Kuk

ICAC

Independent Commission Against Corruption

LegCo

Legislative Council

LP

Liberal Party

MAC

Mutual Aid Committee

NPC

National People's Congress

oc

Owners Corporation

PRC

People's Republic of China

XI

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

Political science research in Hong Kong covers a whole range of topics. Local

political scientists and sociologists focus on topics such as the Legislative Council,

electoral systems, political culture, and voting behaviour, as well as competitive

political party systems.1 In fact, Hong Kong has debated democratization since the

British Hong Kong Government introduced representative government in the early

1980s. Since 1993, several political changes have caught the attention of political

scientists as well as the people of Hong Kong. These changes included former

Governor Mr. Christopher Patten's political reforms, the implementation of Hong

Kong Basic Law, and the frequent elections held for the Legislative Council (LegCo),

the Urban and Regional Councils, and the District Council (formerly Boards). In

1

For examples see, Kuan Hsin-chi et al., Power Transfer & Electoral Politics (Hong Kong: The

Chinese University Press, 1999). See also Rowena Kwok et al., Votes Without Power (Hong Kong:

general, political science research tends to focus on macro-level political phenomena,

such as institutional change and political party systems in transition.

The study of local politics and political party operations at the grassroots level,

however, has been relatively sparse. The interactive personal relationship between

citizens and political elites has received little attention as well. This phenomenon

existed not only in the colonial era, but persists in the post-colonial Hong Kong

Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) of the People's Republic of China (PRC).

Sophisticated personal relationships are crucial for political elites to maintain the trust,

loyalty, emotional support, and affection of Chinese citizens. The importance of these

relationships is demonstrated by the legacy of Chinese personal relationships and

human affections.

1.2 Patron-Client Politics From British Hong Kong Colony to Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region of China

Patron-client politics imply a reciprocal relationship between patrons and their

Hong Kong University Press, 1992).

2

This phenomenon is discussed thoroughly by Andrew Walder in Communist Neo-Traditionism: Work

and Authority in Chinese Industry (California: University of California Press, 1986), pp. 166-189; see

clients. This type of politics existed in Hong Kong under British rule. The British

coopted the Hong Kong elites into various advisory committees and political

institutions, such as the Legislative Council (LegCo) and the Executive Council

(ExCo). Generally, the elites were absorbed into the colonial polity by appointment

and through the rewarding of such titles as Justices of Peace (JP), Master of British

Empire (MBE), and Order of British Empire (OBE). Sociologist Ambrose King

referred to this cooptation as the "administrative absorption of politics."3 British rulers

usually conferred these medals and titles upon the local elites, who were, in turn,

expected to publicly support and promote various government policies.

The patron-client relationship has become more prominent since the

establishment of the HKSAR. One observer noted that a "lack of representation and

the proliferation of clientelism" characterize HKSAR polity.4 It appears that, since

power was handed over to the HKSAR, the administration has rewarded those who

voted for Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa in December of 1996, by appointing them

to various advisory and policy-making bodies. For example, Tung supporters Leung

also Morton Fried, The Fabric of Chinese Society (New York: Praeger, 1953).

3

See King, Ambrose, "Administrative Adsorption of Politics in Hong Kong: Empire on the Grassroots

Level," Asian Survey, Vol. 15, No. 5, (May 1975).

4

Lo, Shiu Hing, "Political Parties, Elites-Mass Gap and Political Instability in Hong Kong",

Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol. 20, No. 1, (April 1998), p. 75.

Chun-ying, Anthony Leung Kam-chung, and Tam Yiu-chung were all appointed to the

ExCo. Anthony Leung was also appointed Financial Secretary in February 2001. In

turn, these political appointees were expected to publicly promote and defend

government policies. If clientelism has become a hallmark of the political arena in the

HKSAR, patron-client relations should be studied not only at the LegCo level, but also

at the grassroots level where local elites regularly interact with the masses.

Since 98 percent of residents in the HKSAR are Chinese, HSKAR is bound to

demonstrate a legacy of personal relationships and human affections. This thesis is

designed to study patron-client politics in Hong Kong. The objectives of this thesis are:

1) to prove that patron-client relations exist between political elites and citizens at the

grassroots level; 2) to examine how the political elites cultivate support from clients in

order to obtain more votes during local elections, and 3) to evaluate the extent to which

patron-client networks are crucial to the electoral victory of candidates.

This Chapter discusses the content of this research, and the concept of

patron-client relations, including the politics of clientelism from the global perspective,

in ex-colonial states and Southeast Asia, and in Chinese society. Chapter two offers a

literature review and analytical framework. This chapter will review literature from

several scholarly perspectives, and will build the original framework used to analyze

the patron-client phenomena in Hong Kong. Chapter three discusses the connections

between patron-client relations and public administration. Chapter four studies the

election of the Chief Executive to discover whether patron-client relations affect this

election in Hong Kong. Chapter five examines the Hong Kong Legislative Council

election to discover how some legislators have become patrons seeking the support of

clients—both local politicians and the masses—and how patron-client relations are

manipulated. Chapter six researches the Hong Kong District Councils election,

focusing on how Councilors cultivate patron-client relationships with the masses.

Chapter six will also study grassroots-level political organizations, such as Mutual

Aids Committees (MACs), Owner's Corporations (OCs), and Heung Yee Kuk (HYK),

focusing on how these local organizations become clients of Legislative Councilors

and District Councilors, and how government has co-opted these organizations.

Chapters four to six make use of the data from a questionnaire-style survey and

face-to-face interviews5 to prove that patron-client politics have a major impact on the

campaign strategy of local politicians. This thesis uses elections at various levels to

discern to what extent patron-client relations exist and are manipulated.

' More details of these three research techniques can be found in Therese Baker, Doing Social Research

1.3 The Concept of Patron-Client Politics

1.3.1 An Overview of Patron-Client Politics

Many political scientists and surveys identify the voting behaviour of HKSAR

voters in elections at the territorial and local levels. Kuan Hsin-chi identified the

political culture in Hong Kong as subject-parochial, rather than participant-oriented.6

Other research reaches a similar conclusion, showing that voters are motivated by

factors such as political instability rather than simply an obligation to fulfill their civic

duty.7 On the other hand, surveys conducted by local newspapers during the 1999

District Councils and Legislative Council elections found that the people of Hong

Kong did vote to fulfill their obligations as citizens. These surveys have scarcely

touched upon the inter-personal relationships between the politicians (i.e., the electoral

candidates) and the citizens (i.e., the voters). This thesis seeks to fill the research gap

to discern what motivates voters to choose certain candidates.

(McGraw-Hill International Editions, 1988), pp. 85-198 and pp. 433-440.

6

Kuan, Hsin-chi, "Power Dependence and Democratic Transition: The Case of Hong Kong," The

China Quarterly (March 1992), p. 777.

7

My unpublished independent research paper written in 1992 regarding the political culture and citizen

participation in District Board elections before 1991. See Kwong, Kam-kwan, Political Culture and

The study of patron-client politics can be regarded as an exploration of the

inter-personal relationships between politicians (the patrons) and voters (the clients).

Its definition is universally applicable and concerns the personal interests of and

benefits to each participant in the relationships. James Scott identified the

relationships between patrons and clients as being distinguished by three factors:

1. Its basis in inequality—the patron supplies goods and services to the clients who

need them for their survival or well-being;

2. Its face-to-face character—the trust and affection that exists between the patron and

clients are based on a continuing pattern of reciprocity;

3. Its diffuse flexibility—it is a strong "multiplex" relationship, unintentionally built

between the two parties; such relationships may be created by personal connection,

tenancy, friendship, past exchange of services, or family ties.8

Scott and Nobutaka Ike noted that patrons typically include local notables,

political bosses, union leaders, local politicians, and leaders of local organizations.9 In

Citizen Participation in District Board Election: 1982-1991, unpublished manuscript, (1992).

8

Scott, James C., "Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast Asia," The American

Political Science Review, Vol. 66, (1972), pp. 92-95.

9

Ike, Nobutaka, "Japanese Political Culture and Democracy," Schmidt, Steffen W. et al., Friends,

Followers, and Factions: A Reader in Political Clientelism (California: University of California Press,

1977), p. 381.

Ike's interpretation of the model, voters "tend to trade their ballots for anticipated

benefits that are particularistic in character - that is: for jobs and favours for

themselves or their relatives; schools, roads, hospitals, and other public works projects

for the community. Political issues and questions of ideology are relatively

unimportant."10 Thus, Ike identifies the benefits received by the clients.

According to Scott, the patrons may make use of scarce resources they control.

They may rely on 1) their own knowledge and skills, such as their professional status

as a lawyer, doctor, local military chief, or teacher; 2) direct control of personal real

estate; and, 3) indirect control of the property or the authority of others (often the

publics).11 Knowledge and skills represent less perishable resources than material

possessions, such as property. Although more time is spent employing these resources,

offering knowledge and skills is a relatively secure means of building a clientele.12

For Scott, patron-client relationships can be divided into two modes, a

10

Ibid.

11

Scott, James C., "Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast Asia," Schmidt, Steffen W.

et al., Friends, Followers, and Factions: A Reader in Political Clientelism (California: University of

California Press, 1977), p. 129.

11

Ibid.

8

patron-client cluster and a patron-client pyramid.13 The former refers to clients who

are directly tied to the patron, whereas the latter involves enlargement of the cluster

while vertically focusing on and linking to the patron.14 These two relationships are

illustrated in Figure 1 below. In the case of the HKSAR, the patron-client cluster is

applied to our analysis of the relationship between local District Councilors and voters

at the grassroots level. The patron-client pyramid applies to our understanding of the

three-level relationships among elected LegCo members, elected District Councilors,

and ordinary citizens.

13

Scott, James C., "Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast Asia," The American

Political Science Review, Vol. 66, (1972), p. 96.

14

Ibid., pp. 96-97.

Figure. 1 Patron-Client Cluster and Pyramid

Patron-Client Cluster

Patron-Client Pyramid

Source: Scott, James C., "Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast

Asia," The American Political Science Review, Vol. 66, (1972), p. 96.

10

Andrew Nathan mentioned similar relationship modes in his study of

factionalism in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Nathan used factions to describe

inter-personal relations15, and through it referred to the same phenomenon as that of

clusters. He also identified the hallmarks of the PRC's clientelist ties, in which 1) a

relationship is between two people, and, 2) members select relationships to be

cultivated from their complete social network. For Nathan, the clientelist tie is

cultivated by the constant exchange of gifts or services. In this exchange, each partner

secures goods or services desired by the other party. Therefore, parties are attractive to

one another when they are dissimilar, and are often unequal in status, wealth or power.

The rights and obligations of each partner must be delineated and can be abolished by

either member. According to Nathan, the tie is not exclusive; either member is free to

establish ties with others so long as they do not involve contradictory obligations.16

Nathan further distinguishes clientist ties in the PRC from power relationships

and exchange relationships.17 Power relationships are superior-subordinate and, in

some cases, authoritative. Exchange relationships refer to "rational, goal-oriented

15

Nathan, Andrew J., " A Factionalism Model for CCP Politics," Schmidt, W. Steffen et al., Friends,

Followers, and Factions: a Reader in Political Clientelism, (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1977), pp. 383-385.

16

Ibid., pp. 382-383.

17

Ibid., pp. 383.

11

behaviour that can profitably be analyzed in terms of exchange."18 By contrast,

Deborah Davis explained that chronic shortages and a bureaucratic system of

allocation are crucial factors when personal connections are used to effectively

position one's self.19 Sinologists like Nathan and Davis also observed the existence

and proliferation of patron-client relations in the PRC.

1.3.2 Anthropological Perspective of Patron-Client Relations

Patron-client politics can be traced back in a study of political anthropology.

Political anthropology originated in the 19th century. Ted Lewellen argued that, in

some tribes, the sociopolitical structure placed upon marriage partners is egalitarian,

0(\

and is based on sets of interpersonal relations. French political anthropologist J.

Maquet has developed three models of political relations in which three elements are

present—the actors, the roles, and the specific content. 21 These models are

summarized in Table 1.1.22 This thesis does not apply the Table to analyze the HKSAR

18

Ibid., pp. 383-384.

19

Davis, Deborah, "Patron and Clients in Chinese Industry," Modern China, Vol. 14, No. 4 (October

1988), p. 494.

20

Lewellen, Ted C., Political Anthropology: An Introduction (Westport: Connecticut, 1992), p. 10.

21

Quoted in Georges Balandies, Political Anthropology, translated by A.M. Sheridan Smith, (London:

Penguin Books Ltd. published, 1972), p. 42.

22

Ibid.

12

case. However, Table 1.1 makes the important point that "interpersonal agreement'"

constitutes the "specific content" of the patron-client relationships.

Table 1.1 Three Orders of Political Relations

Elementary Model Elementary Model Elementary Model

Actors

of Political

of Social

Relations

Stratification

Governors

Superior, equal and

Lord

and

inferior according to

and

governed

position in the order

dependent

of Feudal Relations

of strata

Role

To command

To know how to

Protection

and obey

behave according to

and services

one's status

Physical

Rank

Specific

coercion legitimately

Content

used

Interpersonal

Agreement

Source: Balandies, Georges, Political Anthropology, translated by A.M. Sheridan

Smith (London: Penguin Books Ltd. published, 1972), p. 42.

The first model is not valid in democracies because it involves physical

coercion. To a certain extent, however, the feudal relationship model exists in modern

capitalist society in the exchange of mutual interest, i.e., protection and services.

Georges Balandies interpreted the model of social stratification as a preliminary model

of clientelism.

13

It is, in fact, a relative recent society in its present form (early nineteenth

century), founded on conquest, established on highly differentiated ethnic

entities, in which the state was set up by force and in which the social and

political hierarchies are interlinked. Nevertheless, the office associated with

the royal power confer more in the way of prestige and privilege, and

constitute in a way the hierarchy of reference. Subjacent to the system are

the inequalities set up between ethnic groups and the elementary inequalities

established according to sex, age and position in the kinship and descent

group. The function performed determines a hierarchical order... each group

has an internal, more or less formalized hierarchy and personal success leads

to a kind of promotion.23

For Balandies, sociopolitical relations represent the "relations of clientage, which are

of ties between socially and politically unequal persons."24 Anthropologists also view

the existence of patron-client relations as universal, cutting across feudal and capitalist

societies.

23

Ibid., pp. 93-94.

14

1.3.3 Global Perspective of Patron-Client Relations

Patron-client politics can be found all over the world. Political scientists,

sociologists, and anthropologists study clientelism in places such as Italy, Latin

America, and Southeast Asia.25 For instance, in Colleverde, Italy, the Mezzadria

system formulates the relationships between the lower-class (usually the peasants) and

the landlord or other local person with high status and power.26 Furthermore, the

political

culture

in

Columbia

has

transformed

from

patrimonialism

to

patron-clientelism.27 Highly personalized structures have taken shape in Columbia

where reciprocity is reflected in "an exchange of client labour and loyalty for the

protection of the patron."

Patron-client politics can also be found in well-developed countries such as

France, where there is continuous interaction among the citizens, the notables, and the

24

Ibid, p. 95.

25

Scholars such as Oskar Kurer, James Scott, Rene Lemarchand, S.N. Eisenstadt, and Steffen Schmidt

have written a large volume of books and comparative research articles on this topic. Other scholars

such as Andrew Nathan, Deborah Davis, Yang Lien-sheng wrote on China's clientelism.

26

For a detailed discussion, see Silverman, Sydel F., "Patronage and Community-Nation Relationships

in Central Italy," Schmidt, W. Steffen et al., Friends, Followers, and Factions: a Reader in Political

Clientelism (Berkeley; University of California Press, 1977), pp. 293-304.

27

Martz, John D., The Politics of Clientelism: Democracy & the State in Colombia (New Brunewick:

Transition Publishers, 1997), pp. 35-62.

15

civil servants in both the center of the country (Paris) and in the periphery (the

province).29 During the Fifth Republic, the Gaulist Party of France discovered that the

citizens supported a renowned, high-ranking technocrat with strong local roots,

notable appearance, and local connections. Since the citizens preferred someone with

this profile to serve as their electoral broker, the party agreed to offer The technocrat a

ministerial position in the cabinet.30 Like France, Italy has recently become better at

developing clientelism during elections—a phenomenon labeled by scholars as the

OI

new clientelism. The Christian Democratic Party of Italy, a mass-based party, has

survived by playing the role of a patron depending on the votes and consensus of their

clients. The latter is obtained only in exchange for the tangible benefits dispensed by

the party.32

1.3.4 Patron-Client Relations in Ex-Colonial States

28

Ibid.

29

Medard, Jean-Francois, "Political Clientelism in France: the Centre-Periphery Nexus Reexamined,"

Eisenstadt, S.N. and Rene Lemarchand, eds., Political Clientelism, Patronage and Development,

(SAGA, 1981), p. 129.

30

Ibid., pp. 158-169.

31

A detailed discussion is published in Caciagli, Mario and Frank P. Belloni, "The 'New' Clientelism in

Southern Italy: The Christian Democratic Party in Catania," Eisenstadt, S.N. and Rene Lemarchand,

eds., Political Clientelism, Patronage and Development (SAGA, 1981).

32

Ibid.

16

Patron clientelism provides the authoritative rule commonly present in colonial

regimes with useful means of control. In 1882, soon after the fall of Egypt, brought on

by financial crisis, it was occupied by the British Empire.33 With the hope of making

the transition in Egypt smoother, British settlers attempted to win the loyalty of the

Egyptians. To do so, the settlers offered what the Egyptians wanted most, financial

security. The British solved their financial management needs by attracting the

"European creditors and left something over for public works, agriculture, and

communication" in order to make safeguard their ruling authority34

Under colonial rule in Northern Nigeria, clientelism adopted patron-client

politics for public administration. In Northern Nigeria, officials and vassal are seen as

barori, or clients of the ruler. Smith observed that,

Appointment in the Native Administration is not governed by merit of

technical qualifications, but by ties of loyalty in a situation of political

rivalry where the stakes are considerable. Consequently, in much the same

way that the Emir appoints his own supporters and kin to office, or the Chief

33

Owen, Roger, The Middle East ofEgypt in the World Economy 1800-1914 (London: 1981).

34

Newbury, Cilin, Patrons, Clients and Empire: Chieftaincy and Over-rule in Asia, Africa, and the

Pacific (US: Oxford University Press, p. 84).

17

Judge appoints his kinsmen to judgeships, so do the departmental and

territorial chiefs allocate office on bases of personal loyalty and solidarity to

themselves.35

British colonial rule in Uganda has successfully shifted the loyalty of the local elites

from the Buganda kingdom to the British. To alleviate resistance from Baganda

officials, the British appointed local chiefs and collected taxes to pay the chiefs fixed

salaries from the revenue. Several years after this reform, "many of the Baganda

officials had transferred their loyalty in the outstations to British official patrons who

defined their duties, fixed salaries."36 Vincent stated,

The networks of influence and patronage which engendered Iteso Big

Manship provided the New Men of Teso politics with the makings of a

political machine that went virtually unrecognized by the British until it was

eventually used against them. Big Manship proved not only resilient, but

extraordinary adaptive to the exogenous changes brought about by colonial

35

Smith, M. G., Government in Zazzau: a Study of Government in the Hausa Chiefdom of Zaria in

Northern Nigeria from 1800-1950, (London: 1960, p. 288).

36

Ibid., p. 130.

18

rule.37

The above Ugandan case is actually not exclusive to African post-colonial

regimes. Lord Hailey suggested the adoption of "Native Administration" to deal with

the political changes of British colonies in Africa.38 Smith's insights were similar to

Hailey's work on colonial rule in Africa.

In the absence of developed legal institutions, which Hailey commented on

at length, networks of clientage, personal loyalty, and reciprocal obligations

were still the stuff of civil jurisdiction through nominated "Native Courts"

and resources allocation by "Native Councils," especially for personal

emoluments of chiefs. Appointments to such institutions, he admitted, were

still made "by native custom and usage," that is by exercise of a modicum of

patronage and agreement of elders, clan heads, and in some protectorates,

youngmen s associations.39

37

Vincent, Joan. "Colonial Chiefs and the Making of a Class: A Case Study from Teso, Eastern

Uganda," Africa, vol. 47 (1977), p. 144.

38

Lord Hailey, Native Administration in the British African Territories (London: H.M.S.O.,

1950-1951).

39

Smith, p. 142.

19

In colonized imperial regimes in East Asia, such as Malaya, British settlers

discovered how difficult it was to control a country in which kings ruled several states.

The sultans (kings), rajas (head district men), and the penghulu (village chief) held

several degrees of power to control their own lands. In the late 18th century, Governor

William Robinson offered "conditions of reciprocity in supervising through Malay

hierarchies," including patronage appointments, official status, and supervision of

government programmes.40 The British government prolonged her influential power

in Malaya to assure benefits even after she had retreated, and to insure British heritage

after decolonization. The British found a noble indigenous Malayan, Barrister Tunku

Abdul Rahman, a client of the British Malaya government, to succeed the first Prime

Minister of the independent Malaya government.41 Even now, though Malaya is an

independent Muslim country, she maintains a very close relationship with the British

government in Asia.

Patron-client politics affect ex-colonial countries dominated by tribes and

under-civilized traditions, such as Fiji and Hawaii in Pacific Islands. In both Fiji and

Hawaii, the colonial governments offered official positions and material benefits to

40

Ibid., pp.

41

For details on the independence of Malaya, see Brian Lapping, End of Empire (London: Paladin,

149-176.

1989), Chapter 4.

20

local leaders. Such benefits included taxes and tariffs levied to gain the loyalty and

trust of the people in the settlements. In Fiji, for example, Macnaught's study found

that indigenous chiefs and agents were appointed to official positions and were

delegated certain degrees of power in exchange for their support.42 This constitutes, as

Newbury describes it, a "line of power along which subordinate social and political

units were dependent for access to new resources and services on the actions to chiefly

administrators with ascribed status and prescribed functions who could do favours for

kin and followers."43 Newbury discovered that, although tradition can be seen as

grounds for penalty and rewards in jurisdiction, tradition is "suffused with reciprocal

obligations and access to goods and services on the part of office-holders."44

In Hawaii, where a similar style of governance was found, the sugar trade

presented a major benefit to the United States. The Hawaiian king resisted the

development of this overseas market because of heavy tariffs. The U.S. government,

therefore, made a concession on the tariff as a means of promoting reciprocity. In fact,

the U.S. government used reciprocal relations for political reasons rather than merely

economic salvation. Some believe that the superficial motive of this reciprocity was to

42

Macnaught, Timothy J., The Fijian colonial experience: a study of the neotraditional order under

British colonial rule prior to World War II (Canberra: Australian National University, 1982).

43

Newbury, p. 229.

21

build up patron-client relations with Hawaiians in order to earn their friendship and

trust. However, the underlying reason for the use of reciprocity was to prepare the way

for annexation.45 The reciprocal policy caused the plantation and related interest

groups to urge for constitutional change, resulting in the annexation of Hawaii in

1898 46

According to anthropological studies of global and ex-colonial regimes, the

phenomenon of patron-clientelism stems from human nature. As a result,

patron-clientelism exists regardless of a country's political system or ideology. It

would be easy to assume that patron-client relations exist only in Third World regions

such as Africa, China, and South East Asia, but case studies indicate that developed

countries should not be exempt from the adoption of patron-client relations in their

governance.

The above examples demonstrate how patron-client relations are useful to

politicians as they play political games. Specifically, patron-client relations help to

44

Ibid., p. 230.

45

For details on the mutual relations of the US and Hawaii before annexation, please see Ralph

Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom (Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 1938-1967) and Colin Newbury,

Patronage and Bureaucracy in the Hawaii Kingdom, 1840-1893, PS 24 (2001).

46

Croix, Summer and Christopher Grandy, "The Political Instability of Reciprocal Trade and the

22

build personal relationships and networks with citizens, making governance easier.

They also help politicians gain the support, trust, friendship, and loyalty of the people.

These elements are very crucial for a politician to expand political power through

public recognition. Finally, these relations can even help win the heart of the people so

as to attain the governing role of a state. It is possible, therefore, to skillfully use

patron-client relations in an election at both the national and local level to achieve

victory.

1.3.5 Human Relations and Human Affections in the Chinese Tradition: A Factor

Reinforcing Patron-Client Relations

Apart from the concept of patron-client relations discussed above, human

relation {guanxi) and human affection (ren-ch'ing) are two important concepts in

Chinese society.47 Peter Blau addresses these two concepts using the exchange theory,

stating that "an individual who supplies rewarding services to another obligates him.

Aft

To discharge this obligation, the second must furnish benefits to the first in turn."

There are two types of personal exchange behaviours: economic and social exchange.

Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom," Journal of Economic History 57, (1979).

47

King, Ambrose Y.J., Chinese Society and Culture (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press 1992) pp.

17-85.

23

Economic exchange uses money as its media, is easy to calculate, and is

affective-neutral. Social exchange uses ren-ch 'ing as its exchange media. In each type

of personal exchange, ren-ch'ing is created when the client receives material or

non-material benefits from the patron and thereby becomes obligated to reward the

patron. The client must find ways to fulfill this obligation to the patron or the client

will feel he owes a debt of ren-ch 'ing to the patron.49

Traditional Chinese society sees guanxi (human relations) as an exchange of

personal relationships.50 The success of such an exchange depends on whether it

suitably matches with ren-ch 'ing.51 Ren-ch 'ing refers to the principles of interpersonal

relationships, including affection and reciprocity.52 For example, when you are given a

gift, generally you must give a gift in return. Bruce Jacobs described this kind of

unique relationship as one with particularistic ties, and one that has played an

important role in Chinese politics.53 Andrew Nathan points out that "such ties include

48

Blau, Peter M., Exchange and Power in Social Life, (John Wiley & Sons, 1964), p. 89.

49

King, Ambrose Y.J., Chinese Society and Culture, (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1992), p.

27.

50

Liang, Shuming, Zhongguo wen huayaoyi (Xianggang: San lian shu dian Xianggang fen dian, 1987),

p. 93

51

King, p. 20

52

Feng, Youlan, Xin shi xun : sheng huo fangfaxin lun (Xianggang : Tian di tu shu you xian gong si,

1999.) p. 43.

53

Jacobs is the first one to use this term to illustrate these two phenomena in Chinese society. See Jacobs,

24

patron-client relations, godfather-parent relations, some types of trader-customer

relations...[that] combine to form complex networks which serve many functions,

including social insurance and the mobilization and wielding of influence, i.e. political

conflict."54

Guanxi and ren-ch 'ing have been common in Chinese society for many years.

They highlight the importance of human relations and affection which deeply

influence the Chinese people's philosophy of interpersonal relationships. These

principles also influence clientelism in Hong Kong politics and serve to reinforce

patron-client relations between voters and candidates. These two concepts, as well as

the theory of patron-client relations, will be discussed in depth in the next chapter.

1.3.6 Identifying Benefits of Patron-Client Relations in HKSAR

The exchange of benefits is a major characteristic of patron-client relations.

However, scholars have not explicitly outlined the benefits delivered by the patrons to

the clients. Nor have scholars discussed these benefits in material and non-material

J. Bruce, "A Preliminary Model of Particularistic Ties in Chinese Political Alliances: Kan-Ch'ing and

Kuan-His in a Rural Taiwanese Township." The China Quarterly, (June 1979) No. 18.

54

Nathan, Andrew, p. 24.

25

terms. This section will identify the benefits usually offered by the councilors to the

citizens,55 and will explore councilors' ability to discern whether the benefits they

offer to the clients are those expected by the institution. When what is offered is

institutionally expected, no patron-client relation exists. However, if the offer is not

expected, proof that patron-client relations occurred exists.

Table 1.2 clearly shows that the benefits are both material and non-material.

Material benefits include money and gifts, whereas non-material benefits include

services and activities. Of all these, money sponsorship, trips, and hobby classes are

the benefits most welcomed by the clients and adopted by the District Councilors in

the HKSAR.56

55

Joseph Chan suggested me to discuss the material and non-material benefits in patron-client

relationships. However, scholars studying patron-client politics have not used such analytical categories.

See, for example, Scott, James C., "Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast Asia," The

American Political Science Review, Vol. 66, (1972); Ike, Nobutaka, "Japanese Political Culture and

Democracy" Schmidt, Steffen W. et al., Friends, Followers, and Factions: A Reader in Political

Clientelism (California: University of California Press, 1977); and Nathan, Andrew J., "A Factionalism

Model For CCP Politics," The China Quarterly, No. 53, (January/March 1973).

56

Personal interview with an unnamed District Councilor's personal assistant (hereafter named

informant 1) on 10 February 2001 and an unnamed District Councilor (hereafter named informant 2) on

20 April 2000. The former said that money sponsorship could make people remember that you had sold

them a ren-ch'ing. The latter said that trips allowed him to face hundreds of people at one time, gifts

were usually offered by lucky draw, and the people appreciate you so much.

26

Table 1.2 Exchange of Benefits

Benefits Offered by the

Content

Effect

Reward from the

Councilors

Material

Voters

-

Sponsor with money

Build

-

Offer gifts

personal

-

Free lunch and dinner relations

for

elderly

or

up Vote

for

politician

and

at social network

Mother's Festival

Non-material"

-

Legal consultation

-

Trips

-

Snake soup banquets

-

Chinese opera evening

shows

-

To provide communal

entertainment

activities

Social services, e.g. forms

filling, hobbies class,

etc

** Some of the non-material services provided are free of charge, or under-valued if

payment is required.

57

Personal interview with an unnamed District Councilor's personal assistant (hereafter named

informant 1) on February10,2001 and an unnamed District Councilor (hereafter named informant 2) on

20 April 2000. The former said that money sponsorship could make people remember that you had sold

them a ren-ch'ing. The latter said that trips allowed him to face hundreds of people at one time, gifts

27

the

The content of the benefits and functions of the District Councilors in Hong

Kong makes it obvious that the benefits illustrated in Table 1.2 are not what they are

institutionally expected to offer. Some of the benefits are carried out by social workers,

tourism agencies or District Offices. According to informants 1 and 2, Councilors

enjoy giving benefits because they want to build personal relations with their clients.

According to the social exchange theory, the Councilors expect the clients to

reciprocate by voting for them in the next election.

I will discuss the dimensions of material and non-material benefits in the case

of patron-client politics in Hong Kong. Specifically, what kinds of benefits—material

or non-material—tend to shape the electoral victory of candidates? Are these benefits

prominent in the political landscape of the HKSAR? These questions have not been

explained sufficiently in the precious studies of Hong Kong politics.

were usually offered by lucky draw, and the people appreciate you so much.

28

Occupation

% Interviewees choosing this item Rank

Scientist

59.8%

1

Doctor

34.2%

2

Banker

24.5%

3

Lawyer

22.7%

4

Engineer

19.1%

5

Property Developer

18.4%

6

Architect

18.3%

7

Full-time

16.9%

8

Preacher

14.5%

9

Teacher

12.4%

10

Professional Athlete

12.3%

11

Accountant

11.5%

12

Actor

10.5%

13

Journalist

10.1%

14

Policeman

8.5%

15

Labour Union Leader

6.6%

6.6%

16

Ordinary Businessman

3.4%

17

Legislative Councilor

Source: The Apple Daily, 30 October 2000, p. All.

Note: The sample size was unclear.

29

Table 1.3 lists the most popular occupations in Hong Kong. If knowledge and

skills, such as professional status, are crucial considerations under the concept of

patron-client relations, this ranking is useful in our study of Hong Kong politics. In

fact, no study exists detailing which type of occupation is most likely to win an

election. However, this Table indicates that professionalism is most important to the

people of Hong Kong. Therefore, it can be concluded that professionals will likely be

the most successful group in political campaigns. This assertion, combined with

Scott's observation that skills and knowledge can be used by the patrons to attract

clients, argues that professionalism can be a useful tool in patron-client relations.

1.4 Research Hypotheses and Arguments in the Thesis

This thesis examines whether patron-client relations are critical to the electoral

victory of candidates. It will test the extent to which whether patron-client relations are

crucial in order for candidates to obtain more ballots during elections. It hypothesizes

that the better candidates cultivate patron-client relations, the greater their chance of

winning the election. Moreover, the smaller the size of the electoral constituency, the

greater the impact of patron-client relations. The reason is that smaller constituencies

tend to facilitate the impact of patron-client networks. In short, this thesis seeks to

30

demonstrate the existence and impact of patron-client relations in the HKSAR at the

grassroots level. The thesis will also examine the validity of Scott's three

characteristics of patron-client relations in the context of the HKSAR. These

characteristics of patron-client relations include the following:

1. Its basis in inequality—the patron supplies goods and services to the clients

who need them for their survival or well-being;

2. Its face-to-face character—the trust and affection that exists between the

patron and client are based on a continuing pattern of reciprocity;

3. Its

diffuse flexibility—it is

a

strong

"multiplex" relationship,

unintentionally built between the two parties; such relationships may be

created by personal connection, tenancy, friendship, past exchange of

services, or family ties.58

Furthermore, this thesis will test whether patron-client relations have

contributed to the success and electoral victory of Chief Executive candidates, LegCo

candidates and District Council candidates. Indeed, the electoral success of candidates

may be due to other factors, such as (1) the appeal of political parties, (2) the electoral

system (the functional constituency election in LegCo may favor candidates from

58

Scott. James C., "Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast Asia," The American

31

certain occupational sectors), and (3) the ideology of party candidates. This thesis will

make use of survey data to examine whether these factors, apart from patron-client

networks, play a crucial role in the candidates' electoral success. This thesis

hypothesizes that patron-client relations may be a neglected, though significant, factor

in explaining candidates' electoral success.

1.5 Research Methodology

The study of patron-client politics in elections involves an exploration of the

mutual and dynamic relationships between voters and candidates. From a lay

perspective, nothing special exists within these relationships because voters are

expected to cast their ballots for the candidates they believe are best for the job.

However, the theory of patron-client politics involves an exchange of interest between

the patron (i.e., the candidate) and the clients (i.e., the voters). This exchange of

interest involves both material and non-material benefits. Few citizens publicly admit

that they vote for particular candidates because they have been given some material or

non-material benefits. Similarly, few candidates are likely to admit they won an

election because they offered voters material or non-material interests. As a result, it is

political Science Review, Vol. 66, (1972), pp. 92-95.

32

difficult to collect information from the two parties on the exchange of interest because

it is a highly sensitive political issue. This is especially true when the exchange of

interest involves bribery. As I will discuss in Chapter six, grassroots politics entails

such mysterious exchange in the cases of MACs, OCs, and HYK.

To combat the difficulties of analyzing interest exchange, this thesis adopted

four surveys to collect useful data for further analysis.59 Four surveys involved the

mailing of self-administered questionnaires to newly elected (not appointed) District

Councilors in 1999, Legislative Councilors in 2000, members of the Chief Executive

Election Committee in 2002, and an exit poll in the 2003 District Council elections to

test whether, and to what extent, candidates cultivated patron-client relations. Second,

face-to-face interviews were conducted with the aforementioned elected councilors

and district-level leaders (such as chairpersons and active volunteers of MACs to

clarify their answers on the questionnaire, and to collect additional inside information

concerning the exchange of mutual interests. This thesis therefore makes use of

numerous research instruments, including interviews and various questionnaires

surveys, including exit poll, to understand the dynamics of patron-client politics in the

59

These two research techniques are commonly used by researchers today. The research technique

adopted here refers to Baker, Therese L., Doing Social Research, (McGraw-Hill International, 1988), pp.

165-227.

33

HKSAR.

1.6 Summary

The study of patron-client politics is new to the study of Hong Kong political

science. Many relevant studies have already been conducted in other countries in the

world. The main theme of patron-client politics centers on the exchange of benefits,

either material or non-material. Relative literature has not concretely identified the

benefits received by clients from the patrons. In fact, the literature discusses the

benefits only in broad terms, such as services, human affection, and specific

knowledge and skills held by the patrons.60 The key to success in electoral activities

may depend largely upon 1) closely working at the local level, 2) personal connections

and networks, 3) personal professionalism, social status, and popularity, and 4) the

distribution of benefits. This thesis seeks to assess the extent to which patron-client

networks are crucial in shaping the electoral victory of candidate at different levels.

60

See, for example, Scott, James C., "Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast Asia,"

The American Political Science Review, Vol. 66, (1972); Ike, Nobutaka, "Japanese Political Culture and

Democracy," Schmidt, Steffen W. et al., Friends, Followers, and Factions: A Reader in Political

Clientelism (California: University of California Press, 1977); and Nathan, Andrew J.," A Factionalism

Model for CCP Politics," Schmidt, W. Steffen et al., Friends, Followers, and Factions: a Reader in

Political Clientelism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977).

34

Chapter 2

Toward An Analytical Framework of Analysis

2.1 Introduction

Patron-client relations comprise an inter-disciplinary field of study covered

by anthropology, sociology, psychology, public administration and political science.1

The concept of patron-client relations is not an unusual phenomenon in political

science and public administration, although it is commonly neglected by scholars in

related fields. It is curious that patron-client relations are rarely considered or applied

in the study of electoral behaviour and strategy at all levels of officially recognized

elections. Scholars who cover electoral behaviour and related topics often

1

Many publications focus on this area: for example, E. Gellner and J. Waterbury eds., Patron and

Clients in Mediterranean Societies (London: Duckworth, 1977); K.E. Folsom, Friends, Guests and

Colleagues: The Mu-fu System in the late Ch 'ing Period (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1968); M. Bax, "Patronage Irish Politicians as Brokers," Sociologische Gids, 17, pp. 179-191; E. Fel

and T. Hofer, "Tanyakert-s, Patron-Client Relations and Political Factions in Atany," American

Anthropologist, 75: pp. 787-801; Lucian W. Pye, Warlord Politics: Conflict and Coalition in the

Modernization of Republican China (New York: Prager, 1971); A. Gregory, "Factionalism and the

Indonesian Army. The New Order" Journal of Comparative Administration, 1970, 2(3): pp. 341-354,

and James Stockdale, Courage Under Fire: Testing Epictetus' Doctrines in a Laboratory of Human

Behaviour (Standford: Hoover Institute on War, Revolution, and Peace, 1993). Readers may find it

very useful to understand patron-client relations by reading these publications with different

perspectives. James Stockdale's psychological discussion on love and friendship is especially

interesting.

35

concentrate on inequality, reciprocity and proximity,2 whereas the concept of

exchange relations (the basic element of patron-clientelism) has rarely been

discussed.3

By the same token, sociologists studying exchange theory have tended

to avoid the discussion on the functional power of patron-client relations in human

interaction.

It would be meaningful to conduct an in-depth study of patron-client relations

in a Chinese society such as Hong Kong. Therefore, this thesis is going to adopt two

unique Chinese characteristics, human relations (guanxi) and human affection

(ren-ch'ing) to supplement or reinforce the theoretical framework of patron-client

relations, thus analyzing the actual political behavior in the Chinese setting of Hong

Kong.

This chapter will also review the existing literature on patron-clientelism and

2

It is reasonable to adopt these aspects as fundamental concepts of patron-client relations, because

these aspects are manifested in observations of inter-personal relationship. Please see, for example,

Powell, J.D., "Peasant Society and Clientelism Politics," American Political Science Review, 64 (2):

pp. 411-425; Weingrod, A., "Patrons, Patronage, and Political Parties," Comparative Studies in Society

and History, 10(3): pp. 376-400; Lande, C., "Networks and Groups in Southeast Asia: Some

Observations on the Group Theory of Politics," American Political Science Review, 67(1): pp.

103-127; and Eisenstadt S.N. and Lemarchand, Rene eds., Political Clientelism, Patronage and

Development, contemporary Political Sociology Volume 3, (Beverly Hills : Sage, 1981).

3

Some suggested books on Exchange Theory worth noting are Blau, Peter, "A Theory of Social

Integration," American Journal of Sociology, 65, (1960), pp. 550-553; Von Mises, Ludwig, Human

action; a treatise on economics, (New Haven : Yale University Press, 1949); and Fiedler, Fred Edward,

Leader attitudes and group effectiveness : final report of ONR project NR 170-106, N6 ori-07135,

(Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1981).

36

its dynamic relationship with guanxi and ren-ch 'ing. On basic of these discussions,

an analytical framework will be formulated to seek to explain effective electoral

strategies at different levels. This analytical framework, as suggested below, may be

applied by other scholars to study other societies where patron-client networks

mushroom and persist.

2.2 The Existing Literature on Patron-Client Relations

2.2.1 Exchange Relations and Patron-Client Relations

Social interactions, whether between parents and children, siblings, friends,

classmates, co-workers, or husbands and wives, are unavoidable for anyone living in

the modern world. Sociologists describing these kinds of social associations often

focus on the exchange behavior.4 As Ambrose King points out, exchange behaviour

is a pre-requisite for any social relationship; without such exchange behaviour,

relationships could not function, and no kind of human ethics could be built.5 King's

observation is summarized by the study of social associations:

While structures of social relations are, of course, profoundly influenced by

common values, these structure have a significance of their own, which is

ignored if concern is exclusively with the underlying values and norms.

Exchange transactions and power relations, in particular, constitute social

4

Blau, Peter M., Exchange and Power in Social Life, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1964) p.

4.

5

King, Ambrose, Chinese Society and Culture,(Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1992) pp.

21-22.

37

forces that must be investigated in their own right, not merely in terms of

the norms that limit and the values that reinforce them,.. [FJorces of social

attraction stimulate exchange transactions. Social exchange, in turn, tends

to give rise to differentiation of status and power.6

The starting mechanism that prompts exchange behaviour remains an

interesting question. Marcel Mauss, for example, asserts that the concept of

reciprocity is a key concept of exchange behaviour.7 He explains that individuals

associate with one another because they all profit from their association.8 Lien-sheng

Yang called this kind of reciprocity pao (reward), which is, as he claims, a

fundamental concept in Chinese social association,9 and so pao has become

necessary tool in social exchange theory.10 If pao is so important to the course of

reciprocal relations, then its origin and extent must be discussed, as follows.

According to Blau, once we are sensitized to the concept of social exchange,

it can be observed in a variety of forms:

[N]ot only in market relations but also in friendship and even in love, as we

have seen, as well as in many social relations between these extremes in

intimacy. Neighbours exchange favours; children, toys; colleagues,

6

Ibid., pp. 13-14

Mauss, Marcel, The gift: forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies (London : Cohen &

West, 1954); , and see also Peter P. Ekeh, Social exchange theory: the two traditions (London :

Heinemann Educational, 1974).

8

Blau, p. 18.

9

Yang, Lien-sheng, "The Concept of 'Pao' as a basis for Social Relations in China," in John K.

Fairbank ed., Chinese Thought and Institutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957), pp.

291-309.

10

Ekeh, Social Exchange Theory, p. 32

7

38

assistance; acquaintances, courtesies; politicians, concessions; discussants,

ideas; housewives, recipes.11

When social exchange occurs, the party receiving the benefits (whether material or

non-material) subjectively creates an obligation to repay the party who gives. Since

this reciprocal obligation is a commitment in the process of social exchange, the

giving party trusts that the receiving party will discharge the obligation of reciprocity

at the appropriate time. 12 Although social exchange assigns this reciprocal

commitment to the recipients, it cannot guarantee the trustworthiness of the recipient.

Still, it is reasonable for all parties performing exchange behaviour to express their

willingness to carry on this relation. A fair exchange may reasonably include such an

acceptance. As George Homans elucidates:

[A] man in an exchange relation with another will expect that the rewards

of each man will be proportional to his cost - the greater the rewards, the

greater the cost - and that the net rewards, or profits, of each man be

proportional to his investments - the greater the investments, the greater the

profit.13

Therefore exchange relations provide useful analyses to reinforce our

understanding of patron-client relations on the grounds that both relations study

11

Blau, p. 88; for the discussion of the inter-relationship between love and friendship, please see

Eduardo A. Vel&squez eds., Love and friendship : rethinking politics and affection in modern times,

(Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003).

12

Ibid., pp. 98-99.

13

Homans, George, Social Behavior : its elementary forms, (London : Routledge & Kegan Paul,

1961,) p. 75.

39

reciprocity in human interactions. The patron-client concept can be used to explore

human behaviors and their effects on society; speaking specifically of electoral

politics, it affords politicians electoral strategies to help pursue electoral victory. In

short, reciprocity constitutes the hallmark of both exchange theory and patron-client

relations.

2.2.2 Patron-Client Relations

Typically, patron-client relations occur between two or more parties in the

course of exchanging personal interests or benefits, materially or non-materially. To

phrase it in terms of electoral behaviour, patron-client relations concern

inter-personal relationships between the politicians or candidates (the patrons) and

the citizens or voters (the clients). The exchange of patrons and clients may be

associated with their economic well-being, political power, or social status.14

Clientage can be regarded as a relationship of personal loyalty existing

between superior and subordinates at all levels of the hierarchy as a basis for

confirmation of offices and titles.15 Political clientelism can be distinguished from

economic clientelism in that patrons "do not have to be owners of means of

14

Kurer, Oskar, The political foundations of development policies, (Lanham, Md.: University Press

of America, 1997) p. 31.

15

Whitaker, C.S., The Politics of Tradition: Continuity and change in Northern Nigeria 1946-1966,

(Princeton 1970) p.33.

40

production and therefore the capitalist-worker or landowner-peasant relationship is

not an essential part of the patron-client tie."16 In fact, the players of patronism also

expect prestige or honour as their basic reward.17 A prestigious man may receive

services, commodities, or obedience that may be otherwise inaccessible or less

favorably priced.18 In addition, political charisma may yield more obedient and loyal

followers, so that politicians can enhance their influential power through the

followers' affection.19

In some underdeveloped countries (especially in tribal societies), the

patron-client network is of comparable importance to kinship, in that it involves an

exchange between a superior patron or patron group and an inferior client or client

group; the latter will attach to the former in order to survive in a hostile

environment.20 Vicky Randall and Robin Theobald further explain the formulation

of patron-client relations in underdeveloped societies by citing J.D. Powell's

three-part definition:

1.

The patron-client tie develops between persons who are unequal in

terms of status, wealth and influence.

16

Ibid., p. 35.

Jackson, J. A, Social stratification (London: Cambridge University Press, 1968) p.244.

18

Ibid., p. 247.

19

Evans, Grant, "Political Cults in East and Southeast Asia", in Trankell, Ing-Britt and Laura

Summers, eds., Facets of Power and Its Limitations: Political Culture in Southeast Asia, (Uppsala

University Press, 1998).

20

Randall, Vicky and Robin Theobald, Political Change and Underdevelopment: A Critical

Introduction to Third World Politics, (Basingstoke: Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1985), pp. 50-52.

17

41

2.

The formation and maintenance of the relationship depends upon

reciprocity in the exchange of goods and service. Typically, the

low-status client will receive material assistance in one form or

another whilst his patron will receive less tangible resources such as

deference, esteem, loyalty and perhaps personal services.

3.

The development and maintenance of the relationship depends on

face-to-face contact between the two parties.21

The unequal relations, the element of reciprocity in material and non-material

benefits, and face-to-face contacts echo Scott's delineations of the three features of

patron-client relations as discussed in the previous chapter.

Powell's classifications can used to explain the aspects of patron-client

relations. However, his observations are criticized as comparatively narrow and he

tends to focus on underdeveloped societies; in other words, his definition is rather

particularistic. John Martz, by contrast, has observed that clientelistic systems are

crucial to our understanding of the link between developing regions' national,